Better Late than Never: City on Fire

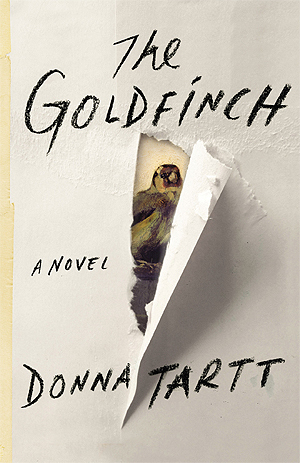

I aim to read one book of 500+ pages in each month of 2017. My first Doorstopper of the Month is City on Fire, the 2015 debut novel from Garth Risk Hallberg. It’s common knowledge that Hallberg earned a six-figure advance for this 911-page evocation of a revolutionary time in New York City. When it was first published I didn’t think I had the fortitude to tackle it and had in mind to wait for the inevitable miniseries instead, but when I won a copy in a goodie bag from Hungerford Bookshop I decided to go for it. I started the novel just after Christmas and finished it a few days ago, so like Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch it took me roughly a month to read because I had many other books on the go at the same time.

Opening on Christmas Eve 1976 and peaking with the July 1977 blackout, the novel brings its diverse cast together through a shooting in Central Park. Insider traders, the aimless second generation of some of the city’s wealthiest aristocrats, anarchist punk rockers, an African-American schoolteacher, a journalist and his Vietnamese neighbor, a fireworks manufacturer, a policeman crippled by childhood polio – the characters fill in the broad canvas of the city, everywhere from Wall Street boardrooms to drug dens.

Opening on Christmas Eve 1976 and peaking with the July 1977 blackout, the novel brings its diverse cast together through a shooting in Central Park. Insider traders, the aimless second generation of some of the city’s wealthiest aristocrats, anarchist punk rockers, an African-American schoolteacher, a journalist and his Vietnamese neighbor, a fireworks manufacturer, a policeman crippled by childhood polio – the characters fill in the broad canvas of the city, everywhere from Wall Street boardrooms to drug dens.

The real achievement is not how Hallberg draws each character but how he fits them all together. The closest comparison I can make is with one of Dickens’s long novels, say David Copperfield, where, especially as you approach the conclusion, you get surprising meet-ups of figures from different realms of life. The relaxed chronology reaches back to the 1950s and forward to 2003 to give hints of where these people came from and what fate holds for them.

City on Fire might sound like a crime drama – I can see a miniseries working in a manner comparable to The Wire – and the mystery of who shot Samantha Cicciaro does indeed last from about page 80 to page 800-something. But finding out who shot her and why (or why investment bankers would be funding a posse of anarchists, or who pushed a journalist into the river) is something of an anticlimax. The journey is the point, and the city is the real star, even though it’s described with a kind of affectionate disdain in the passages that follow:

The stench of the basement level reached him even here, like hot-dog water mixed with roofing tar and left in an alley to rot

The park on New Year’s Day had been a blasted whiteness, or a series of them, hemmed in by black trees like sheets snagged on barbed wire.

It seemed impossible that he’d chosen to live here, at a latitude where spring was a semantic variation on winter, in a grid whose rigid geometry only a Greek or a builder of prisons could love, in a city that made its own gravy when it rained. Taxis continued to stream toward the tunnel, like the damned toward a Boschian hellmouth. Screaming people staggered past below. Impossible, that he now footed the rent entire, two hundred bucks monthly for the privilege of pressing his cheek to the window and still not being able to see spectacular Midtown views. Impossible, that the cinderblock planter on the fire escape could ever have produced flowers.

Or wasn’t this city really the sum of every little selfishness, every ignorance, every act of laziness and mistrust and unkindness ever committed by anybody who lived there, as well as of everything she personally had loved?

Mercer Goodman, Jenny Nguyen and Richard Groskoph were my three favorite characters, and I might have liked to see more of each of them. I also felt that the book as a whole was quite baggy, and the six Interludes that separate the seven large sections, remarkable as they are (especially an entire fanzine, complete with photographs, comics and handwritten articles), weren’t strictly necessary.

It’s definitely a chunkster. For the longest while it felt like I wasn’t making a dent.

Still, I couldn’t help but be impressed by Hallberg’s ambition, and on the sentence level the novel is always well wrought and surprising, with especially lovely last lines that are like a benediction. Though it’s mostly set in the 1970s, this never feels dated; in fact, I thought it thoroughly relevant for our time: “even now they’re writing over history, finding ways to tell you what you just saw doesn’t exist. The big, bad anarchic city, people looting, ooga-booga. Better to trust the developers and the cops.”

I won’t pretend that a 900+-page book isn’t a massive undertaking, and I have some trusted bloggers and Goodreads friends who gave up on this after 250 or 450 pages. So I can’t promise you that you’ll think it’s worth the effort, though for me it was. A modern twist on the Dickensian state-of-society novel, it’s one I’d recommend to fans of Jonathan Franzen, Bill Clegg and Jennifer Egan.

My rating:

Some Final Statistics for 2016

I thought last year’s reading total could never be beat, but somehow I’ve done it. In the meantime I also exceeded my Goodreads goal by a whole 20%. I don’t like to crow, so I’ve worked out the statistics below in terms of percentages rather than absolute numbers. (But, if you’re curious, you can see my final tally here.)

Fiction: 46.2%

Nonfiction: 41.3%

Poetry: 12.5%

Average rating: 3.6 out of 5 stars

Longest book: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

Longest book: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

Shortest book: Physical by Andrew McMillan (in general, reading poetry is one way I boost my reading totals; although the books require time and attention, most only have between 50 and 100 pages)

Average length: 258 pages

Male author: 40.4%

Female author: 59.6%

(Really interesting as I never consciously set out to read more books by women.)

E-books: 33.7%

Print books: 66.3%

(I’m surprised this isn’t closer to half and half!)

Works in translation: 8.3%

(Must do better!)

2016: What a year, huh? World events left so many of us reeling, but books kept me going.

How did 2016 turn out for you reading-wise?

Wishing all of my readers a very happy new year. I look forward to another year of reading and blogging.

Better Late than Never: The Signature of All Things

Who knew Elizabeth Gilbert had it in her? I’ve read and loved all of her nonfiction (e.g. Big Magic), but my experience of her fiction was a different matter: Stern Men is simply atrocious. I’m so glad I took a chance on this 2013 novel anyway. Many friends had lauded it, and for good reason. It’s a warm, playful doorstopper of a book, telling the long and eventful story of Alma Whittaker, a fictional nineteenth-century botanist whose staid life in her father’s Philadelphia home unexpectedly opens outward through marriage, an adventure in Tahiti, and a brush with the theories of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.

Who knew Elizabeth Gilbert had it in her? I’ve read and loved all of her nonfiction (e.g. Big Magic), but my experience of her fiction was a different matter: Stern Men is simply atrocious. I’m so glad I took a chance on this 2013 novel anyway. Many friends had lauded it, and for good reason. It’s a warm, playful doorstopper of a book, telling the long and eventful story of Alma Whittaker, a fictional nineteenth-century botanist whose staid life in her father’s Philadelphia home unexpectedly opens outward through marriage, an adventure in Tahiti, and a brush with the theories of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.

The novel’s voice feels utterly natural, and though Gilbert must have done huge amounts of research about everything from bryophytes to Tahitian customs, nowhere does the level of historical detail feel overwhelming. There are truly terrific characters, including mystical orchid illustrator Ambrose Pike, perky missionary Reverend Welles, and a charismatic Polynesian leader named Tomorrow Morning.

We see multiple sides of Alma herself, like her enthusiasm for mosses and her sexual yearning. For a short time in her girlhood she’s part of a charming female trio with her adopted sister Prudence and their flighty friend Retta. I loved how Gilbert pins down these three very different characters through pithy (and sometimes appropriately botanical) descriptions: “Prudence’s nose was a little blossom; Alma’s was a growing yam,” while Retta is “a perfect little basin of foolishness and distraction.”

Gilbert also captures the delight of scientific discovery and the fecundity of nature in a couple of lush passages that are worth quoting in full:

(Looking at mosses on boulders) Alma put the magnifying lens to her eye and looked again. Now the miniature forest below her gaze sprang into majestic detail. She felt her breath catch. This was a stupefying kingdom. This was the Amazon jungle as seen from the back of a harpy eagle. She rode her eye above the surprising landscape, following its paths in every direction. Here were rich, abundant valleys filled with tiny trees of braided mermaid hair and minuscule, tangled vines. Here were barely visible tributaries running through that jungle, and here was a miniature ocean in a depression in the center of the boulder where all the water pooled.

The cave was not merely mossy; it throbbed with moss. It was not merely green; it was frantically green. It was so bright in its verdure that the color nearly spoke, as though—smashing through the world of sight—it wanted to migrate into the world of sound. The moss was a thick, living pelt, transforming every rock surface into a mythical, sleeping beast.

Best of all, the novel kept surprising me. Every chapter and part took a new direction I never would have predicted. Like The Goldfinch, this is a big, rich novel I can imagine rereading.

My rating:

One of my favorite parts of reviewing (e.g. for Kirkus and BookBrowse) is choosing “readalikes” that pick up on the themes or tone of the book in question. I’ve picked four for The Signature of All Things:

Lab Girl, Hope Jahren: An enthusiastic, wide-ranging memoir of being a woman in science. There’s even some moss! This was a really interesting one for me to be reading at the same time as the Gilbert novel. (See Naomi’s review at Consumed by Ink.)

Lab Girl, Hope Jahren: An enthusiastic, wide-ranging memoir of being a woman in science. There’s even some moss! This was a really interesting one for me to be reading at the same time as the Gilbert novel. (See Naomi’s review at Consumed by Ink.)

Euphoria, Lily King: Based on Margaret Mead’s anthropological research among the tribes of Papua New Guinea in the 1930s, this also has a wonderfully plucky female protagonist.

The Paper Garden, Molly Peacock: This biography of Mary Delany, an eighteenth-century botanical illustrator, examines the options for women’s lives at that time and celebrates the way Delany beat the odds by seeking a career of her own in her seventies.

The Paper Garden, Molly Peacock: This biography of Mary Delany, an eighteenth-century botanical illustrator, examines the options for women’s lives at that time and celebrates the way Delany beat the odds by seeking a career of her own in her seventies.

The Seed Collectors, Scarlett Thomas: A quirky novel full of plants and sex.

Better Late than Never: The Goldfinch

And the painting, above his head, was the still point where it all hinged: dreams and signs, past and future, luck and fate. There wasn’t a single meaning. There were many meanings. It was a riddle expanding out and out and out.

My pristine paperback copy of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch cost all of £1 at a used bookshop in Henley. Talk about entertainment value for money! Although it took me nearly a month to read, starting with Christmas week, it was more gripping than that timeframe seems to suggest. I read it under a pair of cats in the bitter-cold first week of a Pennsylvania January, then tucked it under my arm for airport queues (no way would it fit in my overstuffed carry-on bag) and finally finished it during my first week of bouncing back from transatlantic jetlag. Somehow Theo Decker’s fictional travels – from New York to Las Vegas and back; to Amsterdam and home again – blended with my sense of having been on a literal journey with the book to make this one of my most memorable reading experiences in years.

My pristine paperback copy of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch cost all of £1 at a used bookshop in Henley. Talk about entertainment value for money! Although it took me nearly a month to read, starting with Christmas week, it was more gripping than that timeframe seems to suggest. I read it under a pair of cats in the bitter-cold first week of a Pennsylvania January, then tucked it under my arm for airport queues (no way would it fit in my overstuffed carry-on bag) and finally finished it during my first week of bouncing back from transatlantic jetlag. Somehow Theo Decker’s fictional travels – from New York to Las Vegas and back; to Amsterdam and home again – blended with my sense of having been on a literal journey with the book to make this one of my most memorable reading experiences in years.

That’s not to say that the book was flawless. In fact, I found the first 200 pages or so pretty slow. You almost certainly know the basics of the plot already, but if not, glance away from the rest of this paragraph. Theo, 13, is separated from his mother during a terrorist attack on a New York City museum. Among the dying he encounters an older man – guardian of the pretty red-haired girl Theo had been checking out just moments before – who gives him a ring and tells him to go to Hobart and Blackwell antiques. But this is not the only souvenir Theo takes from his ordeal; he also steals the little Dutch masterpiece by Fabritius that appears on the book’s cover. Stumbling around the streets of New York, the shell-shocked Theo undoubtedly resembles a 9/11 victim. As the years pass, he is moved from guardian to guardian, but a few things remain constant: his memory of his mother, his obsession with the painting, and his love for Pippa, that red-haired girl who, like him, was among the survivors.

The aftermath of the attack was the most tedious section for me. It felt like it took forever for Theo’s future to be set in motion, and I thought if I heard him complain of how his head was killing him one more time I might just scream. It’s when Theo gets to Vegas, and specifically when he meets Boris, that the book really takes off. Boris is simply a terrific character. He’s lived all over and has a mixed-up accent that’s part Australian with heavy Slavic overtones. Like Theo, he has an unreliable father who is often too drunk to care what his kid is doing. This leaves the two young teens free to do whatever they want, usually something classified as illegal. Indeed, there’s a lot of drug use in this book, described in the kind of detail that makes you wonder what Tartt was up to during her years at Bennington.

As a young man Theo, back in New York, joins Hobie (of Hobart and Blackwell) in selling antiques both genuine and ersatz, and reconnects with an old friend’s family in a surprising manner. The story of what becomes of the painting was in danger of turning into a clichéd crime caper, yet Tartt manages to transform it into a richly philosophical interrogation of the nature of fate. Theo’s intimate first-person narration makes him the heir first of Dickensian orphans and later of the kind of tortured antiheroes you’d find in a nineteenth-century Russian novel: “I had the queasy sense of my own life … as a patternless and transient burst of energy, a fizz of biological static just as random as the street lamps flashing past.”

Similar to my experience with Of Human Bondage, I found that the latter part of the novel was the best. The last 200 pages are not only the most addictive plot-wise but also the most introspective; all my Post-It flags congregate here. It’s also full of the best examples of Tartt’s distinctive prose. The best way I can describe it is to say it’s like brush strokes: especially in the scenes set in Amsterdam, she’s creating a still life with words. Often this is through sentences listing images, in phrases separated by commas. Here’s a few examples:

Floodlit window. Mortuary glow from the cold case. Beyond the fog-condensed glass, trickling with water, winged sprays of orchids quivered in the fan’s draft: ghost-white, lunar, angelic.

Out on the street: holiday splendor and delirium. Reflections danced and shimmered on black water: laced arcades above the street, garlands of light on the canal boats.

Medieval city: crooked streets, lights draped on bridges and shining off rain-peppered canals, melting in the drizzle. Infinity of anonymous shops, twinkling window displays, lingerie and garter belts, kitchen utensils arrayed like surgical instruments, foreign words everywhere…

Such sentence construction shouldn’t work, yet it does. I’ve never been one to fawn over Donna Tartt, but this is writing I can really appreciate.

[I did take issue with some of the punctuation in the novel, though whether that’s down to Tartt, her editor or the UK publication team I couldn’t say. Take, for instance, this description of a station clerk: “a broad, fair, middle aged woman, pillowy at the bosom and impersonally genial like a procuress in a second rate genre painting.” Another solid allusion to Dutch art, but missing two hyphens if you ask me.]

The Goldfinch contains multitudes. It’s the Dickensian coming-of-age tale of a hero much like David Copperfield who’s “possessed of a heart that can’t be trusted.” It’s a realist record of criminal escapades. It’s a story of unrequited love. It’s a convincing first-hand picture of anxiety, addiction and regret. It has a great road trip, an endearing small dog, and a last line that rivals The Great Gatsby’s (I’ll leave you to experience it for yourself). It’s a meditation on time, fate and the purpose of art. It’s not perfect, and yet I – even as someone who pretty much never rereads books – can imagine reading this again in the future and gleaning more with hindsight. That makes it worthy of one of my rare 5-star recommendations.

Caring too much for objects can destroy you. Only—if you care for a thing enough, it takes on a life of its own, doesn’t it? And isn’t the whole point of things—beautiful things—that they connect you to some larger beauty? Those first images that crack your heart wide open and you spend the rest of your life chasing, or trying to recapture, in one way or another?

My rating:

More Specific 2016 Goals

Following up on the handful of low-key resolutions I made at the start of the month, I can report that three of my volunteer reviewing positions plus a paid one all seem to have come to a natural end, so that frees me up a little more to seek out big-name opportunities and focus on reading more of the unread books in my own collection plus library copies of books by the authors I’m most keen to try.

Now that nearly one twelfth of this ‘new’ year has passed, I feel like it’s time to set some more specific goals for 2016.

Blogging

Be more strategic about which books I review in full on here. So far it’s just been a random smattering of books I requested online or through publishers. Overall, I don’t feel like I have a clear rationale for which books I feature here and which ones I just respond to via Goodreads. Perhaps I’ll focus on notable reading experiences I feel like drawing attention to (like The Goldfinch recently), or target some pre-release literary fiction to help create buzz.

Start writing more concise reviews. The task of writing just two sentences about my top books from 2015 got me thinking that sometimes less might be more. (See Shannon’s Twitter-length reviews!) Ironically, though, dumping a whole bunch of thoughts about a book can feel easier and less time-consuming than crafting one tight paragraph. As Blaise Pascal said, “I have only made this letter longer because I have not had the time to make it shorter.”

Redesign this blog and get lots of advice from other book bloggers on how to develop it. It’s my one-year anniversary coming up in March and I want to think about what direction to take the site in. I feel like I need to find a niche rather than just post at random.

Update my social media profiles and pictures. In some cases I’m still using photos taken of me nearly three years ago. Not that I’ve changed too much in appearance since then, but I might as well stay current!

Leisure Reading

Make it through my backlog of giveaway books. In the photo below, the books on the left I won through Goodreads giveaways, and the pile on the right I won through various other giveaways, usually through Twitter or publisher newsletters.

Although there is no strict compulsion to review the books you win, it’s an informal obligation I’d like to honor. Before too many months go by, then, I’d like to read and review them all. That’ll help me meet the next goal…

Get down to 100 or fewer unread books in the flat by the end of the year. Although this seems like an achievable goal, it does mean getting through about 100 of the books we own, on top of any review books that come up throughout the year, not to mention my Kindle backlog from NetGalley and Edelweiss (so I am definitely NOT counting those in the 100!).

Weed our bookshelves. Alas, it’s looking like we’re going to be moving again in August, so before then it would be great if I could reduce our overflow areas so that everything can fit on our four matching bookcases with little or no double-stacking. I’ll start by picking out the books I’ve already read and don’t think I’ll read or refer to again. Which brings me to a related goal…

Start a Little Free Library or make another arrangement for giving away proof copies. Advanced copies technically should not be resold, so ones I don’t want to keep I tend to give away to friends and family or to a thrift store if they don’t too obviously look like proofs (i.e. they have a finished cover and don’t say “Proof copy” in enormous letters). I figure if a charity shop can get £1 for the copy, why not? It’s a perfectly good, readable book. However, I should really come up with a better solution. If not an LFL, then maybe I could arrange to keep a giveaway box outside a charity shop or at the train station wherever we next live.

Career

Take control of my e-mail inboxes. There are currently over 11,000 messages in my personal account and nearly 1,100 in my professional account. I attribute this partly to sentimentality and partly to fear of deleting something important I might need to reference later.

Find a way to incorporate exercise into my workday. I really, really need a treadmill desk. Or any piece of exercise equipment with a ledge that would hold a Kindle or laptop. That way I could continue reading and writing so that working out wouldn’t feel like lost time. Otherwise I am far too sedentary in my normal life.

Apropos of nothing, but always worth remembering.

What are some of your updated goals for 2016 – reading-related or otherwise?

Review: Bradstreet Gate by Robin Kirman

Sometimes a book is crushed by the weight of its own hype, with people objecting that the blurb is overblown or even misleading. Bradstreet Gate, the debut novel by Robin Kirman, has a score of 2.77 on Goodreads, the average of over 800 ratings. That’s pretty low. What went wrong? If you ask most people, it’s because the book’s supposed similarity to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History set them up to have their sky-high expectations disappointed.

Now, I like Donna Tartt as much as the next person: I’ve read her first two novels and have been saving up The Goldfinch for my Christmas read this year. But I don’t idolize her like some do, so I quite enjoyed Bradstreet Gate. You can certainly see why the Secret History connections were made during the marketing process: both novels concern a New England campus murder and the complicated relationships between the various characters involved.

Now, I like Donna Tartt as much as the next person: I’ve read her first two novels and have been saving up The Goldfinch for my Christmas read this year. But I don’t idolize her like some do, so I quite enjoyed Bradstreet Gate. You can certainly see why the Secret History connections were made during the marketing process: both novels concern a New England campus murder and the complicated relationships between the various characters involved.

The crime takes place at Harvard in 1997, but the novel opens 10 years later with Georgia Calvin Reece. When she’s approached by a student reporter who wants to write a piece about the ten-year anniversary of Julie Patel’s murder, Georgia is so burnt out with caring for a new baby and a husband who’s dying of cancer that she can’t take the time to engage with her memories. Yet she can’t ignore them either.

In college her closest friends were Charles Flournoy and Alice Kovac, both of whom had crushes on her. She knew Julie only peripherally through a volunteer organization, but she knew the man who was presumed but never proven to have killed her – an ex-military professor and dorm master named Rufus Storrow – all too well. They were having a top-secret affair at the time that Julie was found strangled near Harvard’s Bradstreet Gate.

I enjoyed how Kirman dives into the past to look at the history of the central trio. Georgia was raised by a photographer father who took nude portraits of her. Growing up in New Jersey, Charles felt weak compared to his aggressive father and brother. Alice’s family traded Belgrade for Wisconsin. The novel also zeroes in on a point about four years after the characters’ graduation, when Georgia is traveling in India, Charlie has a high-flying job in New York City, and Alice – perhaps the most interesting character – is in a mental hospital.

We never learn quite as much about Storrow as about the other characters, and that’s deliberate. He’s an almost mythical figure, cleverly described as being like Jay Gatsby:

Storrow had been too perfect a target, after all: too well dressed and too well spoken, with a high Virginia drawl and the sort of fair, delicate good looks that called to mind outdated notions like breeding.

Whatever his faults, Storrow was a good man, Charles believed. He might even turn out to be a great man … There was a tragic element to the man: in his outmoded brand of dignity.

A man like Storrow, so devoted to the perfection of his image; he wouldn’t allow himself to be remembered as a villain, or to be forgotten either.

I hope I won’t disappoint you if I say the book doesn’t reveal who the real murderer is. It’s not that kind of mystery. With its focus on the aftermath of tragedy, this reminded me of Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng or Did You Ever Have a Family by Bill Clegg. Kirman’s writing is also slightly reminiscent of Jeffrey Eugenides’s or A.M. Homes’s. I’d definitely read another novel from her. Let’s hope that next time the marketing does it justice.

With thanks to Blogging for Books for the free e-copy.

My rating:

I Like Big Books and I Cannot Lie

You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.

~ C. S. Lewis

Here’s to doorstoppers! Books of 500 pages or more [the page count is in brackets for each of the major books listed below] can keep you occupied for entire weeks of a summer – or for just a few days if they’re gripping enough. There’s something delicious about getting wrapped up in an epic story and having no idea where the plot will take you. Doorstoppers are the perfect vacation companions, for instance. I have particularly fond memories of getting lost in Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke [782] on a week’s boating holiday in Norfolk with my in-laws, and of devouring The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber [835] on a long, queasy ferry ride to France.

Here’s to doorstoppers! Books of 500 pages or more [the page count is in brackets for each of the major books listed below] can keep you occupied for entire weeks of a summer – or for just a few days if they’re gripping enough. There’s something delicious about getting wrapped up in an epic story and having no idea where the plot will take you. Doorstoppers are the perfect vacation companions, for instance. I have particularly fond memories of getting lost in Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke [782] on a week’s boating holiday in Norfolk with my in-laws, and of devouring The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber [835] on a long, queasy ferry ride to France.

I have an MA in Victorian Literature, so I was used to picking up novels that ranged between 600 and 900 pages. Of course, one could argue that the Victorians were wordier than necessary due to weekly deadlines, the space requirements of serialized stories, and the popularity of subsequent “triple-decker” three-volume publication. Still, I think Charles Dickens’s works, certainly, stand the test of time. His David Copperfield [~900] is still my favorite book. I adore his sprawling stories crammed full of major and minor characters. Especially in a book like David Copperfield that spans decades of a character’s life, the sheer length allows you time to get to know the protagonist intimately and feel all his or her struggles and triumphs as if they were your own.

I felt the same about A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara [720], which I recently reviewed for Shiny New Books. Jude St. Francis is a somewhat Dickensian character anyway, for his orphan origins at least, and even though the novel is told in the third person, it is as close a character study as you will find in contemporary literature. I distinctly remember two moments in my reading, one around page 300 and one at 500, when I looked up and thought, “where in the world will this go?!” Even as I approached the end, I couldn’t imagine how Yanagihara would leave things. That, I think, is one mark of a truly masterful storyteller.

Speaking of Dickensian novels, in recent years I’ve read two Victorian pastiches that have an authentically Victorian page count, too: The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton [848] and Death and Mr. Pickwick by Stephen Jarvis [816]. The Luminaries, which won the 2013 Booker Prize, has an intricate structure (based on astrological charts) that involves looping back through the same events – making it at least 200 pages too long.

It was somewhat disappointing to read Jarvis’s debut novel in electronic format; without the physical signs of progress – a bookmark advancing through a huge text block – it’s more difficult to feel a sense of achievement. Once again one might argue that the book’s digressive nature makes it longer than necessary. But with such an accomplished debut that addresses pretty much everything ever written or thought about The Pickwick Papers, who could quibble?

John Irving’s novels are Dickensian in their scope as well as their delight in characters’ eccentricities, but fully modern in terms of themes – and sexual explicitness. Along with Dickens, he’s a mutual favorite author for my husband and me, and his A Prayer for Owen Meany [637] numbers among our collective favorite novels. Most representative of his style are The World According to Garp and The Cider House Rules.

Here are a handful of other long novels I’ve read and reviewed within the last few years (the rating is below each description):

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr [531] – The 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner; set in France and Germany during World War II.

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr [531] – The 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner; set in France and Germany during World War II.

In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman [555] – Digressive intellectualizing about race, class and war as they pertain to British immigrants.

The Son by Philipp Meyer [561] – An old-fashioned Western with hints of Cormac McCarthy.

The Son by Philipp Meyer [561] – An old-fashioned Western with hints of Cormac McCarthy.

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach [512] – Baseball is a window onto modern life in this debut novel about homosocial relationships at a small liberal arts college.

“A Discovery of Witches” fantasy trilogy by Deborah Harkness: A Discovery of Witches [579], Shadow of Night [584], and The Book of Life [561] – Thinking girl’s vampire novels, with medieval history and Oxford libraries thrown in.

“A Discovery of Witches” fantasy trilogy by Deborah Harkness: A Discovery of Witches [579], Shadow of Night [584], and The Book of Life [561] – Thinking girl’s vampire novels, with medieval history and Oxford libraries thrown in.

And here’s the next set of doorstoppers on the docket:

Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham [766] – A Dickensian bildungsroman about a boy with a clubfoot who pursues art, medicine and love.

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt [864] – I have little idea of what this is actually about. A boy named Theo, art, loss, drugs and 9/11? Or just call it life in general. I’ve read Tartt’s other two books and was enough of a fan to snatch up a secondhand paperback for £1.

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James [686] (as with A Little Life, the adjective in the title surely must be tongue-in-cheek!) – The starting point is an assassination attempt on Bob Marley in the late 1970s, but this is a decades-sweeping look at Jamaican history. I won a copy in a Goodreads giveaway.

A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth [1,474!] – A sprawling Indian family saga. Apparently he’s at work on a sequel entitled A Suitable Girl.

This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson [744] – A novel about Charles Darwin and his relationship with Robert FitzRoy, captain of the Beagle.

The Last Chronicle of Barset by Anthony Trollope [891] – As the title suggests, this is the final novel in Trollope’s six-book “Chronicles of Barsetshire” series. Alas, reading this one requires reading the five previous books, so this is more like a 5,000-page commitment…

Now, a confession: sometimes I avoid long books because they just seem like too much work. It’s sad but true that a Dickens novel takes me infinitely longer to read than a modern novel of similar length. The prose is simply more demanding, there’s no question about it. So if I’m faced with a choice between one 800-page novel that I know could take me months of off-and-on reading and three or four 200–300-page contemporary novels, I’ll opt for the latter every time. Part of this also has to do with meeting my reading goals for the year: when you’re aiming for 250 titles, it makes more sense to read a bunch of short books than a few long ones. I need to get better about balancing quality and quantity.

How do you feel about long books? Do you seek them out or shy away? Comments welcome!

Twenty-two-year-old Tess arrives in New York City by car in June 2006. Two days later she interviews at a restaurant in Union Square and gets a job as a backwaiter and barista. Camaraderie makes the restaurant not just bearable but a kind of substitute home. Tess is most fascinated by two colleagues who stand apart from the crowd: Simone, the resident wine know-it-all, and bartender Jake. Try as she might, Tess can’t work out the dynamic between them. To mirror her one-year taste apprenticeship, the book is broken into four seasonal parts, headed by short sections in the second person or first-person plural. Everything about this novel is utterly assured: the narration, the characterization, the prose style, the plot, the timing. It’s hard to believe that Danler is a debut author rather than a seasoned professional. It captures the intensity and idealism of youth yet injects a hint of nostalgia. I’m willing to go out on a limb and call Sweetbitter my favorite novel of 2016.

Twenty-two-year-old Tess arrives in New York City by car in June 2006. Two days later she interviews at a restaurant in Union Square and gets a job as a backwaiter and barista. Camaraderie makes the restaurant not just bearable but a kind of substitute home. Tess is most fascinated by two colleagues who stand apart from the crowd: Simone, the resident wine know-it-all, and bartender Jake. Try as she might, Tess can’t work out the dynamic between them. To mirror her one-year taste apprenticeship, the book is broken into four seasonal parts, headed by short sections in the second person or first-person plural. Everything about this novel is utterly assured: the narration, the characterization, the prose style, the plot, the timing. It’s hard to believe that Danler is a debut author rather than a seasoned professional. It captures the intensity and idealism of youth yet injects a hint of nostalgia. I’m willing to go out on a limb and call Sweetbitter my favorite novel of 2016. My Son, My Son opens in working-class Manchester in the 1870s and stretches through the aftermath of World War I. Like a Dickensian urchin, William Essex escapes his humble situation thanks to a kind benefactor and becomes a writer. His best friend is Dermot O’Riorden, a fervid Irish Republican. William’s and Dermot’s are roughly parallel tracks. Their sons’ lives, however, are a different matter. Oliver Essex and Rory O’Riorden are born on the same day, and it’s clear at once that both fathers intend to live vicariously through their sons. My Son, My Son struck me as an unusual window onto World War I, a subject I’ve otherwise wearied of in fiction. A straight line could be drawn between Great Expectations, Maugham’s

My Son, My Son opens in working-class Manchester in the 1870s and stretches through the aftermath of World War I. Like a Dickensian urchin, William Essex escapes his humble situation thanks to a kind benefactor and becomes a writer. His best friend is Dermot O’Riorden, a fervid Irish Republican. William’s and Dermot’s are roughly parallel tracks. Their sons’ lives, however, are a different matter. Oliver Essex and Rory O’Riorden are born on the same day, and it’s clear at once that both fathers intend to live vicariously through their sons. My Son, My Son struck me as an unusual window onto World War I, a subject I’ve otherwise wearied of in fiction. A straight line could be drawn between Great Expectations, Maugham’s

This is such an outrageous racial satire that I kept asking myself how Beatty got away with it. Not only did he get away with it, he won a National Book Critics Circle Award. The novel opens at the U.S. Supreme Court, where the narrator has been summoned to defend himself against a grievous but entirely true accusation: he has reinstituted slavery and segregation in his hometown of Dickens, California. All the old stereotypes of African Americans are here, many of them represented by Hominy Jenkins. This reminded me most of Ishmael Reed’s satires and, oddly enough, Julian Barnes’s England, England, which similarly attempts to distill an entire culture and history into a limited space and time. The plot is downright silly in places, but the shock value keeps you reading. Even so, after the incendiary humor of the first third, the satire wears a bit thin. I yearned for more of an introspective Bildungsroman, which there are indeed hints of.

This is such an outrageous racial satire that I kept asking myself how Beatty got away with it. Not only did he get away with it, he won a National Book Critics Circle Award. The novel opens at the U.S. Supreme Court, where the narrator has been summoned to defend himself against a grievous but entirely true accusation: he has reinstituted slavery and segregation in his hometown of Dickens, California. All the old stereotypes of African Americans are here, many of them represented by Hominy Jenkins. This reminded me most of Ishmael Reed’s satires and, oddly enough, Julian Barnes’s England, England, which similarly attempts to distill an entire culture and history into a limited space and time. The plot is downright silly in places, but the shock value keeps you reading. Even so, after the incendiary humor of the first third, the satire wears a bit thin. I yearned for more of an introspective Bildungsroman, which there are indeed hints of.

Dillard was raised a Christian in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but her writing expresses an open spirituality rather than any specific faith. For readers who are reasonably familiar with her work, the selection given here might be a little disappointing. Why reread 60 pages from Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, I thought, when I have a copy of it up on the shelf? Rather than reading long, downright strange portions of For the Time Being and Teaching a Stone to Talk, why not go find whole copies to read (which might help with understanding them in context)? None of Dillard’s poetry or fiction has been included, and the most recent piece, “This Is the Life,” from Image magazine, is from 2002. I wish there could have been more fresh material as an enticement for existing fans. However, this will serve as a perfect introduction for readers who are new to Dillard’s work and want a taste of the different nonfiction genres she treats so eloquently and mysteriously.

Dillard was raised a Christian in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but her writing expresses an open spirituality rather than any specific faith. For readers who are reasonably familiar with her work, the selection given here might be a little disappointing. Why reread 60 pages from Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, I thought, when I have a copy of it up on the shelf? Rather than reading long, downright strange portions of For the Time Being and Teaching a Stone to Talk, why not go find whole copies to read (which might help with understanding them in context)? None of Dillard’s poetry or fiction has been included, and the most recent piece, “This Is the Life,” from Image magazine, is from 2002. I wish there could have been more fresh material as an enticement for existing fans. However, this will serve as a perfect introduction for readers who are new to Dillard’s work and want a taste of the different nonfiction genres she treats so eloquently and mysteriously.