Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

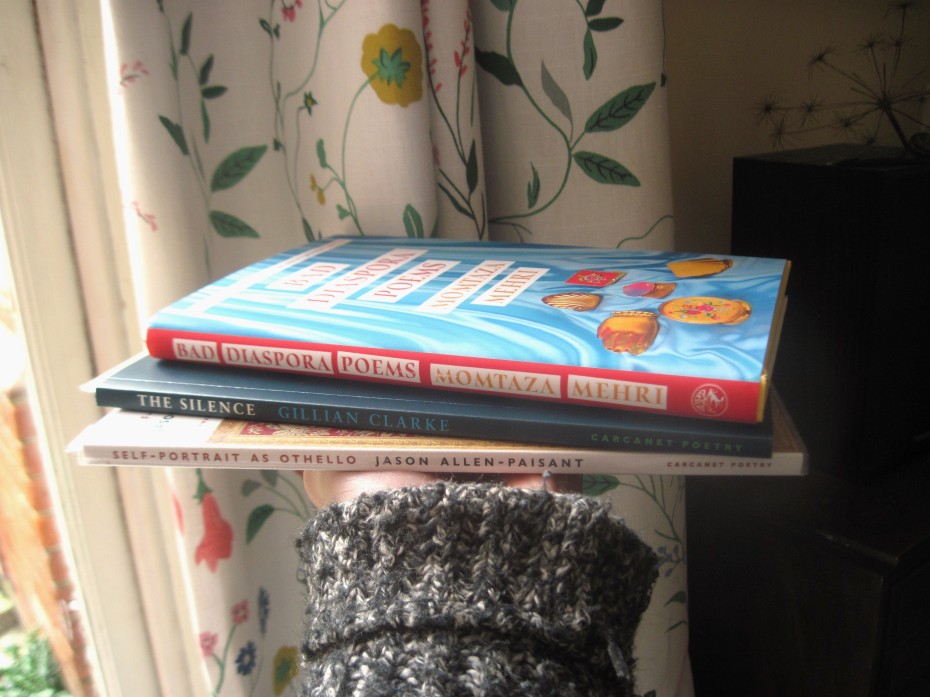

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

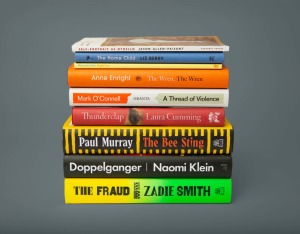

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

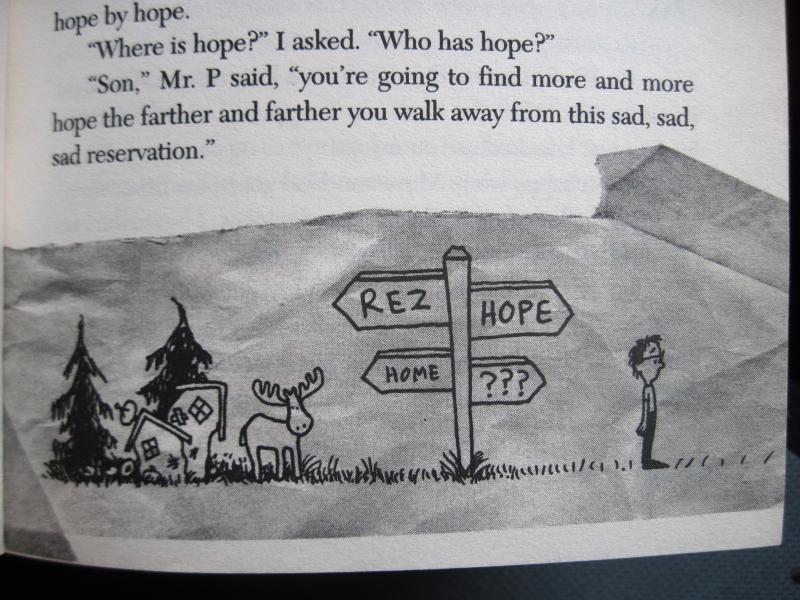

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Miscellaneous #ReadIndies Reviews: Mostly Poetry + Brown, Sands

Catching up on a few final #ReadIndies contributions in early March! Short responses to some indie reading I did from my shelves over the course of last month.

Bloodaxe Books:

Parables & Faxes by Gwyneth Lewis (1995)

I was surprised to discover this was actually my fourth book by Lewis, a bilingual Welsh author: two memoirs, one of depression and one about marriage; and now two poetry collections. The table of contents suggest there are only 16 poems in the book, but most of the titles are actually headings for sections of anywhere between 6 and 16 separate poems. She ranges widely at home and abroad, as in “Welsh Espionage” and the “Illinois Idylls.” “I shall taste the tang / of travel on the atlas of my tongue,” Lewis writes, an example of her alliteration and sibilance. She’s also big on slant and internal rhymes – less so on end rhymes, though there are some. Medieval history and theology loom large, with the Annunciation featuring more than once. I couldn’t tell you now what that many of the poems are about, but Lewis’s telling is always memorable.

I was surprised to discover this was actually my fourth book by Lewis, a bilingual Welsh author: two memoirs, one of depression and one about marriage; and now two poetry collections. The table of contents suggest there are only 16 poems in the book, but most of the titles are actually headings for sections of anywhere between 6 and 16 separate poems. She ranges widely at home and abroad, as in “Welsh Espionage” and the “Illinois Idylls.” “I shall taste the tang / of travel on the atlas of my tongue,” Lewis writes, an example of her alliteration and sibilance. She’s also big on slant and internal rhymes – less so on end rhymes, though there are some. Medieval history and theology loom large, with the Annunciation featuring more than once. I couldn’t tell you now what that many of the poems are about, but Lewis’s telling is always memorable.

Sample lines:

For the one

who said yes,

how many

said no?

…

But those who said no

for ever knew

they were damned

to the daily

as they’d disallowed

reality’s madness,

its astonishment.

(from “The ‘No’ Madonnas,” part of “Parables & Faxes”)

(Secondhand purchase – Westwood Books, Sedbergh)

&

Fields Away by Sarah Wardle (2003)

Wardle’s was a new name for me. I saw two of her collections at once and bought this one as it was signed and the themes sounded more interesting to me. It was her first book, written after inpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Many of the poems turn on the contrast between city (London Underground) and countryside (fields and hedgerows). Religion, philosophy, and Greek mythology are common points of reference. End rhymes can be overdone here, and I found a few of the poems unsubtle (“Hubris” re: colonizers and “How to Be Bad” about daily acts of selfishness vs. charity). However, there are enough lovely ones to compensate: “Flight,” “Word Tasting” (mimicking a wine tasting), “After Blake” (reworking “Jerusalem” with “And will chainsaws in modern times / roar among England’s forests green?”), “Translations” and “Word Hill.”

Wardle’s was a new name for me. I saw two of her collections at once and bought this one as it was signed and the themes sounded more interesting to me. It was her first book, written after inpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Many of the poems turn on the contrast between city (London Underground) and countryside (fields and hedgerows). Religion, philosophy, and Greek mythology are common points of reference. End rhymes can be overdone here, and I found a few of the poems unsubtle (“Hubris” re: colonizers and “How to Be Bad” about daily acts of selfishness vs. charity). However, there are enough lovely ones to compensate: “Flight,” “Word Tasting” (mimicking a wine tasting), “After Blake” (reworking “Jerusalem” with “And will chainsaws in modern times / roar among England’s forests green?”), “Translations” and “Word Hill.”

Favourite lines:

(oh, but the last word is cringe!)

Catkin days and hedgerow hours

fleet like shafts of chapel sun.

Childhood in a cobwebbed bower

guards a treasure chest of fun.

(from “Age of Awareness”)

(Secondhand purchase – Carlisle charity shop)

Carcanet Press:

Tripping Over Clouds by Lucy Burnett (2019)

The title is a setup for the often surrealist approach, but where another Carcanet poet, Caroline Bird, is warm and funny with her absurdism, Burnett is just … weird. Like, I’d get two stanzas into a poem and have no idea what was going on or what she was trying to say because of the incomplete phrases and non-standard punctuation. Still, this is a long enough collection that there are a good number of standouts about nature and relationships, and alliteration and paradoxes are used to good effect. I liked the wordplay in “The flight of the guillemet” and the off-beat love poem “Beer for two in Brockler Park, Berlin.” The noteworthy Part III is composed of 34 ekphrastic poems, each responding to a different work of (usually modern) art.

The title is a setup for the often surrealist approach, but where another Carcanet poet, Caroline Bird, is warm and funny with her absurdism, Burnett is just … weird. Like, I’d get two stanzas into a poem and have no idea what was going on or what she was trying to say because of the incomplete phrases and non-standard punctuation. Still, this is a long enough collection that there are a good number of standouts about nature and relationships, and alliteration and paradoxes are used to good effect. I liked the wordplay in “The flight of the guillemet” and the off-beat love poem “Beer for two in Brockler Park, Berlin.” The noteworthy Part III is composed of 34 ekphrastic poems, each responding to a different work of (usually modern) art.

Favourite lines:

This is a place of uncalled-for space

and by the grace of the big sky,

and the serrated under-silhouette of Skye,

an invitation to the sea unfolds

to come and dine with mountain.

(from “Big Sands”)

(New (bargain) purchase – Waterstones website)

&

The Met Office Advises Caution by Rebecca Watts (2016)

The problem with buying a book mostly for the title is that often the contents don’t live up to it. (Some of my favourite ever titles – An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam – were of books I couldn’t get through). There are a lot of nature poems here, which typically would be enough to get me on board, but few of them stood out to me. Trees, bats, a dead hare on the road; maps, Oxford scenes, Christmas approaching. All nice enough; maybe it’s just that the poems don’t seem to form a cohesive whole. Easy to say why I love or hate a poet’s style; harder to explain indifference.

The problem with buying a book mostly for the title is that often the contents don’t live up to it. (Some of my favourite ever titles – An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam – were of books I couldn’t get through). There are a lot of nature poems here, which typically would be enough to get me on board, but few of them stood out to me. Trees, bats, a dead hare on the road; maps, Oxford scenes, Christmas approaching. All nice enough; maybe it’s just that the poems don’t seem to form a cohesive whole. Easy to say why I love or hate a poet’s style; harder to explain indifference.

Sample lines:

Branches lash out; old trees lie down and don’t get up.

A wheelie bin crosses the road without looking,

lands flat on its face on the other side, spilling its knowledge.

(from the title poem)

(New (bargain) purchase – Amazon with Christmas voucher)

Faber:

Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown (2020)

The title signals right away how these linked autobiographical essays split the ‘I’ from the body – Brown resents the fact that disability limits her experience. Oxygen deprivation at their premature birth led to her twin sister’s death and left her with cerebral palsy severe enough that she generally uses a wheelchair. In Bologna for a travel fellowship, she writes, “There are so many places that I want to be, but I can’t take my body anywhere. But I must take my body everywhere.” A medieval city is particularly unfriendly to those with mobility challenges, but chronic pain and others’ misconceptions (e.g. she overheard a guy on her college campus lamenting that she’d die a virgin) follow her everywhere.

The title signals right away how these linked autobiographical essays split the ‘I’ from the body – Brown resents the fact that disability limits her experience. Oxygen deprivation at their premature birth led to her twin sister’s death and left her with cerebral palsy severe enough that she generally uses a wheelchair. In Bologna for a travel fellowship, she writes, “There are so many places that I want to be, but I can’t take my body anywhere. But I must take my body everywhere.” A medieval city is particularly unfriendly to those with mobility challenges, but chronic pain and others’ misconceptions (e.g. she overheard a guy on her college campus lamenting that she’d die a virgin) follow her everywhere.

A poet, Brown earned minor fame for her first collection, which was about historical policies of enforced sterilization for the disabled and mentally ill in her home state of Virginia. She is also a Catholic convert. I appreciated her exploration of poetry and faith as ways of knowing: “both … a matter of attending to the world: of slowing my pace, and focusing my gaze, and quieting my impatient, indignant, protesting heart long enough for the hard shell of the ordinary to break open and reveal the stranger, subtler singing underneath.” This is part of a terrific run of three pieces, the others about sex as a disabled person and the odious conservatism of the founders of Liberty University. Also notable: “Fragments, Never Sent,” letters to her twin; and “Frankenstein Abroad,” about rereading this novel of ostracism at its 200th anniversary. (Secondhand purchase – Amazon)

New River Books:

The Hedgehog Diaries: A Story of Faith, Hope and Bristle by Sarah Sands (2023)

Reasons for reading: 1) I’d enjoyed Sands’s The Interior Silence and 2) Who can resist a book about hedgehogs? She covers a brief slice of 2021–22 when her aged father was dying in a care home. Having found an ill hedgehog in her garden and taken it to a local sanctuary, she developed an interest in the plight of hedgehogs. In surveys they’re the UK’s favourite mammal, but it’s been years since I saw one alive. Sands brings an amateur’s enthusiasm to her research into hedgehogs’ place in literature, philosophy and science. She visits rescue centres, meets activists in Oxfordshire and Shropshire who have made hedgehog welfare a local passion, and travels to Uist to see where hedgehogs were culled in 2004 to protect ground-nesting birds’ eggs. The idea is to link personal brushes with death with wider threats of extinction. Unfortunately, Sands’s lack of expertise is evident. This was well-meaning, but inconsequential and verging on twee. (Christmas gift from my wishlist)

Reasons for reading: 1) I’d enjoyed Sands’s The Interior Silence and 2) Who can resist a book about hedgehogs? She covers a brief slice of 2021–22 when her aged father was dying in a care home. Having found an ill hedgehog in her garden and taken it to a local sanctuary, she developed an interest in the plight of hedgehogs. In surveys they’re the UK’s favourite mammal, but it’s been years since I saw one alive. Sands brings an amateur’s enthusiasm to her research into hedgehogs’ place in literature, philosophy and science. She visits rescue centres, meets activists in Oxfordshire and Shropshire who have made hedgehog welfare a local passion, and travels to Uist to see where hedgehogs were culled in 2004 to protect ground-nesting birds’ eggs. The idea is to link personal brushes with death with wider threats of extinction. Unfortunately, Sands’s lack of expertise is evident. This was well-meaning, but inconsequential and verging on twee. (Christmas gift from my wishlist)

A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley (Blog Tour)

Silver Moon, one of the Charing Cross Road bookshops, was a London institution from 1984 until its closure in 2001. “Feminism and business are strange bedfellows,” Jane Cholmeley soon realised, and this book is her record of the challenges of combining the two. On the spectrum of personal to political, this is much more manifesto than memoir. She dispenses with her own story (vicar’s tomboy daughter, boarding school, observing racism on a year abroad in Virginia, secretarial and publishing jobs, meeting her partner) via a 10-page “Who Am I?” opening chapter. However, snippets of autobiography do enter into the book later on; in one of my favourite short chapters, “Coming Out,” Cholmeley recalls finally telling her mother that she was a lesbian after she and Sue had been together nearly a decade.

The mid-1980s context plays a major role: Thatcherite policies (Section 28 outlawing the “promotion of homosexuality”), negotiations with the Greater London Council, and trying to share the landscape with other feminist bookshops like Sisterwrite and Virago. Although there were some low-key rivalries and mean-spirited vandalism, a spirit of camaraderie generally prevailed. Cholmeley estimates that about 30% of the shop’s customers were men, but the focus here was always on women. The events programme featured talks by an amazing who’s-who of women authors, Cholmeley was part of the initial roundtable discussions in 1992 that launched the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize), and the café was designated a members’ club so that it could legally be a women-only space.

I’ve always loved reading about what goes on behind the scenes in bookshops (The Diary of a Bookseller, Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop, The Sentence, The Education of Harriet Hatfield, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap, and so on), and Cholmeley ably conveys the buzzing girl-power atmosphere of hers. There is a fun sense of humour, too: “Dyke and Doughnut” was a potential shop name, and a letter to one potential business partner read, “you already eat lentils, and ride a bicycle, so your standard of living hasn’t got much further to fall, we happen to like you an awful lot, and think we could all work together in relative harmony”.

However, the book does not have a narrative per se; the “A Day in the Life of… (1996)” chapter comes closest to what those hoping for a bookseller memoir might be expecting, in that it actually recreates scenes and dialogue. The rest is a thematic chronicle, complete with lists, sales figures, profitability charts, and excerpted documents, and I often got lost in the detail. The fact that this gives the comprehensive history of one establishment makes it a nostalgic yearbook that will appeal most to readers who have a head for business, were dedicated Silver Moon customers, and/or hold a particular personal or academic interest in the politics of the time and the development of the feminist and LGBT movements.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Mudlark for the free copy for review.

Buy A Bookshop of One’s Own from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was happy to be part of the blog tour for the release of this book. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Three “Love” or “Heart” Books for Valentine’s Day: Ephron, Lischer and Nin

Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet put together a themed post featuring books that have “Love” or a similar word in the title. This is the eighth year in a row, in fact (after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023)! Today I’m looking at two classic novellas, one of them a reread and the other my first taste of a writer I’d expected more from; and a wrenching, theologically oriented bereavement memoir.

Heartburn by Nora Ephron (1983)

I’d already pulled this out for my planned reread of books published in my birth year, so it’s pleasing that it can do double duty here. I can’t say it better than my original 2013 review:

The funniest book you’ll ever read about heartbreak and betrayal, this is full of wry observations about the compromises we make to marry – and then stay married to – people who are very different from us. Ephron readily admitted that her novel is more than a little autobiographical: it’s based on the breakdown of her second marriage to investigative journalist Carl Bernstein (All the President’s Men), who had an affair with a ludicrously tall woman – one element she transferred directly into Heartburn.

Ephron’s fictional counterpart is Rachel Samstad, a New Yorker who writes cookbooks or, rather, memoirs with recipes – before that genre really took off. Seven months pregnant with her second child, she has just learned that her second husband is having an affair. What follows is her uproarious memories of life, love and failed marriages. Indeed, as Ephron reflected in a 2004 introduction, “One of the things I’m proudest of is that I managed to convert an event that seemed to me hideously tragic at the time to a comedy – and if that’s not fiction, I don’t know what is.”

As one might expect from a screenwriter, there is a cinematic – that is, vivid but not-quite-believable – quality to some of the moments: the armed robbery of Rachel’s therapy group, her accidentally flinging an onion into the audience during a cooking demonstration, her triumphant throw of a key lime pie into her husband’s face in the final scene. And yet Ephron was again drawing on experience: a friend’s therapy group was robbed at gunpoint, and she’d always filed the experience away in a mental drawer marked “Use This Someday” – “My mother taught me many things when I was growing up, but the main thing I learned from her is that everything is copy.” This is one of celebrity chef Nigella Lawson’s favorite books ever, for its mixture of recipes and rue, comfort food and folly. It’s a quick read, but a substantial feast for the emotions.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Still, the dialogue, the scenes, the snarky self-portrayal: it all pops. This was autofiction before that was a thing, but anyone working in any genre could learn how to write readable content by studying Ephron. “‘I don’t have to make everything into a joke,’ I said. ‘I have to make everything into a story.’ … I think you often have that sense when you write – that if you can spot something in yourself and set it down on paper, you’re free of it. And you’re not, of course; you’ve just managed to set it down on paper, that’s all.” (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013):

My rating now:

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer (2013)

“What we had taken to be a temporary unpleasantness had now burrowed deep into the family pulp and was gnawing us from the inside out.” Like all life writing, the bereavement memoir has two tasks: to bear witness and to make meaning. From a distance that just happens to be Mary Karr’s prescribed seven years, Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him that his melanoma, successfully treated the year before, was back. Tests revealed that the cancer’s metastases were everywhere, including in his brain, and were “innumerable,” a word that haunted Lischer and his wife, their daughter, and Adam’s wife, who was pregnant with their first child.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The facts of the story are heartbreaking enough, but Lischer’s prose is a perfect match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose. He approaches the documenting of his son’s too-short life with a sense of sacred duty: “I have acquired a new responsibility: I have become the interpreter of his death. God, I must do a better job. … I kissed his head and thanked him for being my son. I promised him then that his death would not ruin my life.” This memoir brought back so much about my brother-in-law’s death from brain cancer in 2015, from the “TEAM [ADAM/GARNET]” T-shirts to Adam’s sister’s remark, “I never dreamed this would be our family’s story.” We’re not alone. (Remainder book from the Bowie, Maryland Dollar Tree)

A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin (1954)

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

Come on, though, “fecundated,” “fecundation” … who could take such vocabulary seriously? Or this sex writing (snort!): “only one ritual, a joyous, joyous, joyous impaling of woman on a man’s sensual mast.” I charge you to use the term “sensual mast” wherever possible in the future. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Newbury)

But hey, check out my score for the Faber Valentine’s quiz!

After Nicholas’s death in 2018, Brownrigg was compelled to trace her family’s patterns of addiction and creativity. It’s a complex network of relatives and remarriages here. The family novels and letters were her primary sources, along with a scrapbook her great-grandmother Beatrice made to memorialize Gawen for Nicholas. Certain details came to seem uncanny. For instance, her grandfather’s first novel, Star Against Star, was about, of all things, a doomed lesbian romance – and when Brownrigg first read it, at 21, she had a girlfriend.

After Nicholas’s death in 2018, Brownrigg was compelled to trace her family’s patterns of addiction and creativity. It’s a complex network of relatives and remarriages here. The family novels and letters were her primary sources, along with a scrapbook her great-grandmother Beatrice made to memorialize Gawen for Nicholas. Certain details came to seem uncanny. For instance, her grandfather’s first novel, Star Against Star, was about, of all things, a doomed lesbian romance – and when Brownrigg first read it, at 21, she had a girlfriend. This memoir of Ernaux’s mother’s life and death is, at 58 pages, little more than an extended (auto)biographical essay. Confusingly, it covers the same period she wrote about in

This memoir of Ernaux’s mother’s life and death is, at 58 pages, little more than an extended (auto)biographical essay. Confusingly, it covers the same period she wrote about in  The remote Welsh island setting of O’Connor’s debut novella was inspired by several real-life islands that were depopulated in the twentieth century due to a change in climate and ways of life: Bardsey, St Kilda, the Blasket Islands, and the Aran Islands. (A letter accompanying my review copy explained that the author’s grandmother was a Welsh speaker from North Wales and her Irish grandfather had relatives on the Blasket Islands.)

The remote Welsh island setting of O’Connor’s debut novella was inspired by several real-life islands that were depopulated in the twentieth century due to a change in climate and ways of life: Bardsey, St Kilda, the Blasket Islands, and the Aran Islands. (A letter accompanying my review copy explained that the author’s grandmother was a Welsh speaker from North Wales and her Irish grandfather had relatives on the Blasket Islands.)

I requested this because a) I had enjoyed Wood’s novels

I requested this because a) I had enjoyed Wood’s novels  Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

Mitchell was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in her fifties and was an energetic campaigner for dementia education and research for the last decade of her life. With a co-author, she wrote three books that give a valuable insider’s view of life with dementia:

Mitchell was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in her fifties and was an energetic campaigner for dementia education and research for the last decade of her life. With a co-author, she wrote three books that give a valuable insider’s view of life with dementia:

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

Some of you may know Lory, who is training as a spiritual director, from her blog,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,

These 17 flash fiction stories fully embrace the possibilities of magic and weirdness, particularly to help us reconnect with the dead. Brad and I are literary acquaintances from our time working on (the now defunct) Bookkaholic web magazine in 2014–15. I liked this even more than his first book,  I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

I had a misconception that each chapter would be written by a different author. I think that would actually have been the more interesting approach. Instead, each character is voiced by a different author, and sometimes by multiple authors across the 14 chapters (one per day) – a total of 36 authors took part. I soon wearied of the guess-who game. I most enjoyed the frame story, which was the work of Douglas Preston, a thriller author I don’t otherwise know.

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.

“Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned. Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors (

Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors ( I knew from

I knew from  The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of