Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

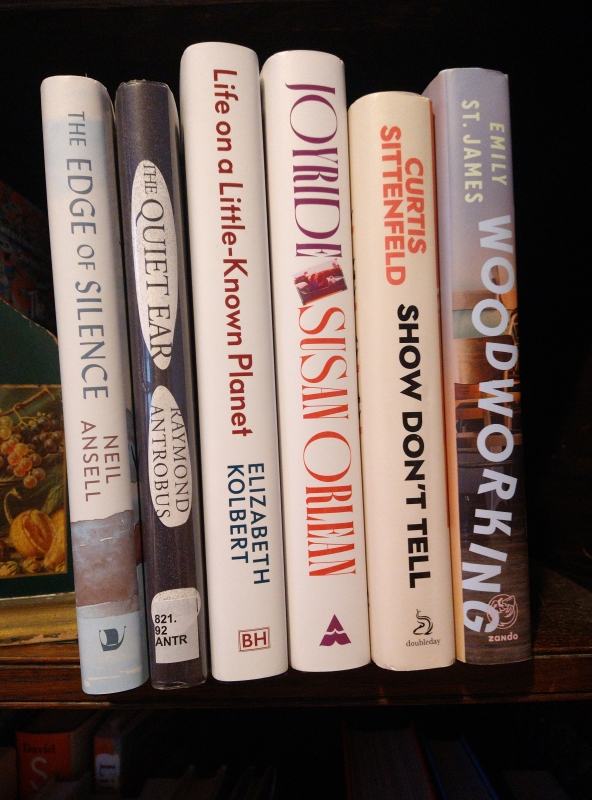

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

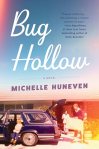

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

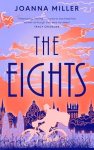

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Reading from the Wainwright Prize Longlists

The Wainwright Prize is one that I’ve ended up following closely almost by accident, simply because I tend to read most of the nature books released in the UK in any given year. A few months back I cheekily wrote to the prize director, proffering myself as a judge and appending a list of eligible titles I hoped were in consideration. Although they already had a full judging roster for 2021, I got a very kind reply thanking me for my recommendations and promising to bear me in mind for the future. Fifteen of my 25 suggestions made it onto the lists below.

This is the second year that there have been two awards, one for writing on UK nature and the other on global conservation themes. Tomorrow (August 4th) at 4 p.m., the longlists will be narrowed down to shortlists. I happened to have read and reviewed 12 of the nominees already, and I have a few others in progress.

UK nature writing longlist:

The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell: Hoping to reclaim an ancestral connection, Ansell visited the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. He weaves together his personal story, the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, and the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. The New Forest is a model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access. (On my Best of 2021 so far list.)

The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell: Hoping to reclaim an ancestral connection, Ansell visited the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. He weaves together his personal story, the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, and the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. The New Forest is a model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access. (On my Best of 2021 so far list.)

T he Screaming Sky by Charles Foster: A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, Foster is obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves birds and other creatures no place to live. He delivers heaps of information on the birds but refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. The book quotes frequently from poetry and the prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and whimsy. (Also on my Best of 2021 so far list.)

he Screaming Sky by Charles Foster: A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, Foster is obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves birds and other creatures no place to live. He delivers heaps of information on the birds but refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. The book quotes frequently from poetry and the prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and whimsy. (Also on my Best of 2021 so far list.)

Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour: As an aimless twentysomething, Gilmour tried to rekindle a relationship with his unreliable poet father at the same time that he and his wife were pondering starting a family of their own. Meanwhile, he was raising Benzene, a magpie that fell out of the nest and ended up in his care. The experience taught him responsibility and compassionate care for another creature. Gilmour makes elegant use of connections and metaphors. He’s so good at scenes, dialogue and emotion – a natural writer.

Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour: As an aimless twentysomething, Gilmour tried to rekindle a relationship with his unreliable poet father at the same time that he and his wife were pondering starting a family of their own. Meanwhile, he was raising Benzene, a magpie that fell out of the nest and ended up in his care. The experience taught him responsibility and compassionate care for another creature. Gilmour makes elegant use of connections and metaphors. He’s so good at scenes, dialogue and emotion – a natural writer.

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer: Hamer paints a loving picture of his final year at the 12-acre British garden he tended for decades. In few-page essays, the book journeys through a gardener’s year. This is creative nonfiction rather than straightforward memoir. The prose is adorned with lovely metaphors. In places, the language edges towards purple and the content becomes repetitive – a danger of the diary format. However, the focus on emotions and self-perception – rare for a male nature writer – is refreshing. (Reviewed for Foreword.)

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer: Hamer paints a loving picture of his final year at the 12-acre British garden he tended for decades. In few-page essays, the book journeys through a gardener’s year. This is creative nonfiction rather than straightforward memoir. The prose is adorned with lovely metaphors. In places, the language edges towards purple and the content becomes repetitive – a danger of the diary format. However, the focus on emotions and self-perception – rare for a male nature writer – is refreshing. (Reviewed for Foreword.)

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison: A collection of five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. Initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. I appreciate how hands-on and practical Harrison is. She never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife and get involved in citizen science projects. (Reviewed for Shiny New Books.)

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison: A collection of five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. Initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. I appreciate how hands-on and practical Harrison is. She never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife and get involved in citizen science projects. (Reviewed for Shiny New Books.)

Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt: During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. Lovatt’s writing is introspective and poetic, delighting in metaphors for sounds.

Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt: During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. Lovatt’s writing is introspective and poetic, delighting in metaphors for sounds.

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald: Though written for various periodicals and ranging in topic from mushroom-hunting to deer–vehicle collisions and in scope from deeply researched travel pieces to one-page reminiscences, these essays form a coherent whole. Equally reliant on argument and epiphany, the book has more to say about human–animal interactions in one of its essays than some whole volumes manage. Her final lines are always breath-taking. I’d rather read her writing on any subject than almost any other author’s. (My top nonfiction release of 2020.)

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald: Though written for various periodicals and ranging in topic from mushroom-hunting to deer–vehicle collisions and in scope from deeply researched travel pieces to one-page reminiscences, these essays form a coherent whole. Equally reliant on argument and epiphany, the book has more to say about human–animal interactions in one of its essays than some whole volumes manage. Her final lines are always breath-taking. I’d rather read her writing on any subject than almost any other author’s. (My top nonfiction release of 2020.)

Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss: Devoting a chapter each to the first 13 weeks of the initial UK lockdown, Moss traces the season’s development in Somerset alongside his family’s experiences and what was emerging on the national news. He welcomed migrating birds and marked his first sightings of butterflies and other insects. Nature came to him, too. For once, he felt that he had truly appreciated the spring, noting its every milestone and “rediscovering the joys of wildlife-watching close to home.”

Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss: Devoting a chapter each to the first 13 weeks of the initial UK lockdown, Moss traces the season’s development in Somerset alongside his family’s experiences and what was emerging on the national news. He welcomed migrating birds and marked his first sightings of butterflies and other insects. Nature came to him, too. For once, he felt that he had truly appreciated the spring, noting its every milestone and “rediscovering the joys of wildlife-watching close to home.”

Thin Places by Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I received a proof copy from Canongate and twice tried the first few pages, but couldn’t wade through the excessive lyricism (and downright incorrect information – weaving a mystical description of a Winter Moth’s flight, she keeps referring to the creature as “she,” whereas when I showed the passage to my entomologist husband he told me that the females of that species are flightless). I’m told it develops into an eloquent memoir of growing up during the Troubles. Perhaps reminiscent of The Outrun?

Thin Places by Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I received a proof copy from Canongate and twice tried the first few pages, but couldn’t wade through the excessive lyricism (and downright incorrect information – weaving a mystical description of a Winter Moth’s flight, she keeps referring to the creature as “she,” whereas when I showed the passage to my entomologist husband he told me that the females of that species are flightless). I’m told it develops into an eloquent memoir of growing up during the Troubles. Perhaps reminiscent of The Outrun?

Into the Tangled Bank by Lev Parikian: A delightfully Bryson-esque tour that moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature. With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. (When I reviewed this in July 2020, I correctly predicted it would make the longlist!)

Into the Tangled Bank by Lev Parikian: A delightfully Bryson-esque tour that moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature. With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. (When I reviewed this in July 2020, I correctly predicted it would make the longlist!)

English Pastoral by James Rebanks: This struck me for its bravery, good sense and humility. The topics of the degradation of land and the dangers of intensive farming are of the utmost importance. Daring to undermine his earlier work and his online persona, the author questions the mythos of modern farming, contrasting its practices with the more sustainable and wildlife-friendly ones his grandfather espoused. Old-fashioned can still be best if it means preserving soil health, river quality and the curlew population.

English Pastoral by James Rebanks: This struck me for its bravery, good sense and humility. The topics of the degradation of land and the dangers of intensive farming are of the utmost importance. Daring to undermine his earlier work and his online persona, the author questions the mythos of modern farming, contrasting its practices with the more sustainable and wildlife-friendly ones his grandfather espoused. Old-fashioned can still be best if it means preserving soil health, river quality and the curlew population.

I Belong Here by Anita Sethi: I recently skimmed this from the library. Two things are certain: 1) BIPOC writers should appear more frequently on prize lists, so it’s wonderful that Sethi is here; 2) this book was poorly put together. It’s part memoir of an incident of racial abuse, part political manifesto, and part quite nice travelogue. The parts don’t make a whole. The contents are repetitive and generic (definitions, overstretched metaphors). Sethi had a couple of strong articles here, not a whole book. I blame her editors for not eliciting better.

I Belong Here by Anita Sethi: I recently skimmed this from the library. Two things are certain: 1) BIPOC writers should appear more frequently on prize lists, so it’s wonderful that Sethi is here; 2) this book was poorly put together. It’s part memoir of an incident of racial abuse, part political manifesto, and part quite nice travelogue. The parts don’t make a whole. The contents are repetitive and generic (definitions, overstretched metaphors). Sethi had a couple of strong articles here, not a whole book. I blame her editors for not eliciting better.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn: I only skimmed this, too. I got the feeling her publisher was desperate to capitalize on the popularity of her first book and said “give us whatever you have,” cramming drafts of several different projects (a memoir that went deeper into the past, a ‘what happened next’ sequel to The Salt Path, and an Iceland travelogue) into one book and rushing it through to publication. Winn’s writing is still strong, though; she captures dialogue and scenes naturally, and you believe in how much the connection to the land matters to her.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn: I only skimmed this, too. I got the feeling her publisher was desperate to capitalize on the popularity of her first book and said “give us whatever you have,” cramming drafts of several different projects (a memoir that went deeper into the past, a ‘what happened next’ sequel to The Salt Path, and an Iceland travelogue) into one book and rushing it through to publication. Winn’s writing is still strong, though; she captures dialogue and scenes naturally, and you believe in how much the connection to the land matters to her.

Global conservation longlist:

Like last year, I’ve read much less from this longlist since I gravitate more towards nature writing and memoirs than to hard or popular science. So I have read, am reading or plan to read about half of this list, as opposed to pretty much all of the other one.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: This was on my Most Anticipated list for 2021 and I treated myself to a copy while we were up in Northumberland. I’m nearly a third of the way through this fascinating, well-written tour of places where nature has spontaneously regenerated due to human neglect: depleted mining areas in Scotland, former conflict zones, Soviet collective farms turned feral, sites of nuclear disaster, and so on. I’m about to start the chapter on Chernobyl, which I expect to echo Mark O’Connell’s Notes from an Apocalypse.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: This was on my Most Anticipated list for 2021 and I treated myself to a copy while we were up in Northumberland. I’m nearly a third of the way through this fascinating, well-written tour of places where nature has spontaneously regenerated due to human neglect: depleted mining areas in Scotland, former conflict zones, Soviet collective farms turned feral, sites of nuclear disaster, and so on. I’m about to start the chapter on Chernobyl, which I expect to echo Mark O’Connell’s Notes from an Apocalypse.

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen: The message of this controversial 2019 New Yorker essay is simple: climate breakdown is here, so stop denying it and talking of “saving the planet”; it’s too late. Global warming is locked in; the will is not there to curb growth, overhaul economies, and ask people to relinquish developed world lifestyles. Instead, start preparing for the fallout (refugees) and saving what can be saved (particular habitats and species). Franzen is realistic about human nature and practical about what to do next.

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen: The message of this controversial 2019 New Yorker essay is simple: climate breakdown is here, so stop denying it and talking of “saving the planet”; it’s too late. Global warming is locked in; the will is not there to curb growth, overhaul economies, and ask people to relinquish developed world lifestyles. Instead, start preparing for the fallout (refugees) and saving what can be saved (particular habitats and species). Franzen is realistic about human nature and practical about what to do next.

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake: Sheldrake’s enthusiasm is infectious as he researches fungal life in the tropical forests of Panama, accompanies truffle hunters in Italy, and takes part in a clinical study on the effects of LSD (derived from a fungus). More than a travel memoir, though, this is a work of proper science – over 100 pages are taken up by notes, bibliography and index. This is a perspective-altering text that reveals our unconscious species bias. I’ve recommended it widely, even to those who tend not to read nonfiction.

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake: Sheldrake’s enthusiasm is infectious as he researches fungal life in the tropical forests of Panama, accompanies truffle hunters in Italy, and takes part in a clinical study on the effects of LSD (derived from a fungus). More than a travel memoir, though, this is a work of proper science – over 100 pages are taken up by notes, bibliography and index. This is a perspective-altering text that reveals our unconscious species bias. I’ve recommended it widely, even to those who tend not to read nonfiction.

Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham: I have this out from the library and am two-thirds through. Wadham, a leading glaciologist, introduces readers to the science of glaciers: where they are, what lives on and under them, how they move and change, and the grave threats they face (and, therefore, so do we). The science, even dumbed down, is a little hard to follow, but I love experiencing extreme landscapes like Greenland and Antarctica with her. She neatly inserts tiny mentions of her personal life, such as her mother’s death, a miscarriage and a benign brain cyst.

Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham: I have this out from the library and am two-thirds through. Wadham, a leading glaciologist, introduces readers to the science of glaciers: where they are, what lives on and under them, how they move and change, and the grave threats they face (and, therefore, so do we). The science, even dumbed down, is a little hard to follow, but I love experiencing extreme landscapes like Greenland and Antarctica with her. She neatly inserts tiny mentions of her personal life, such as her mother’s death, a miscarriage and a benign brain cyst.

The rest of the longlist is:

- A Life on Our Planet by David Attenborough – I’ve never read a book by Attenborough (and tend to worry this sort of book would be ghostwritten), but wouldn’t be averse to doing so.

Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs – All about whales. Kate raved about it. I have this on hold at the library.

Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs – All about whales. Kate raved about it. I have this on hold at the library.- Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change by Dieter Helm

- Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert – I have read her before and would again.

- Riders on the Storm by Alistair McIntosh – My husband has read several of his books and rates them highly.

- The New Climate War by Michael E. Mann

- The Reindeer Chronicles by Judith D. Schwartz – I’ve been keen to read this one.

- A World on the Wing by Scott Weidensaul – My husband is reading this from the library.

My predictions/wishes for the shortlists:

It’s high time that a woman won again. And why not for both, eh? (Amy Liptrot is still the only female winner in the Prize’s seven-year history, for The Outrun in 2016.)

UK nature writing:

- The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell

- The Screaming Sky by Charles Foster

- Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour

- Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald*

- English Pastoral by James Rebanks

- I Belong Here by Anita Sethi

- The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

Writing on global conservation:

- Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn*

- Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs

- Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert

- Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

- Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham

- A World on the Wing by Scott Weidensaul

*Overall winners, if I had my way.

Have you read anything from the Wainwright Prize longlists?

Do any of these books interest you?

Books in Brief: Five I Loved Recently

The Human Age: The World Shaped by Us

By Diane Ackerman

A perfect tonic to books like The Sixth Extinction, this is an intriguing and inspiring look at how some of the world’s brightest minds are working to mitigate the negative impacts we have had on the environment and improve human life through technology. As in David R. Boyd’s The Optimistic Environmentalist, Ackerman highlights some innovative programs that are working to improve the environment. Part 1 is the weakest – most of us are already all too aware of how we’ve trashed nature – but the book gets stronger as it goes on. My favorite chapters were the last five, about 3D printing, bionic body parts and human–animal hybrids created for medical use, and how epigenetics and the microbial life we all harbor might influence our personality and behavior more than we think.

A perfect tonic to books like The Sixth Extinction, this is an intriguing and inspiring look at how some of the world’s brightest minds are working to mitigate the negative impacts we have had on the environment and improve human life through technology. As in David R. Boyd’s The Optimistic Environmentalist, Ackerman highlights some innovative programs that are working to improve the environment. Part 1 is the weakest – most of us are already all too aware of how we’ve trashed nature – but the book gets stronger as it goes on. My favorite chapters were the last five, about 3D printing, bionic body parts and human–animal hybrids created for medical use, and how epigenetics and the microbial life we all harbor might influence our personality and behavior more than we think.

My rating:

I Will Find You

By Joanna Connors

Connors was a young reporter running late for an assignment for the Cleveland Plain-Dealer when she was raped in an empty theatre on the Case Western campus. Using present-tense narration, she makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday. It wasn’t until 2005 that Connors, about to send her daughter off to college, felt the urge to go public about her experience. “I will find you,” her rapist had warned her as he released her from the theatre, but she turned the words back on him, locating his family and learning everything she could about what made him a repeat criminal. She never uses this to explain away what he did, but it gives her the necessary compassion to visit the man’s grave. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

Connors was a young reporter running late for an assignment for the Cleveland Plain-Dealer when she was raped in an empty theatre on the Case Western campus. Using present-tense narration, she makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday. It wasn’t until 2005 that Connors, about to send her daughter off to college, felt the urge to go public about her experience. “I will find you,” her rapist had warned her as he released her from the theatre, but she turned the words back on him, locating his family and learning everything she could about what made him a repeat criminal. She never uses this to explain away what he did, but it gives her the necessary compassion to visit the man’s grave. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

My rating:

One of Us: The Story of a Massacre and Its Aftermath

By Åsne Seierstad

An utterly engrossing account of Anders Behring Breivik’s July 22, 2011 attacks on an Oslo government building (8 dead) and the political youth camp on the island of Utøya (69 killed). Over half of this hefty tome is prologue: Breivik’s life story, plus occasional chapters giving engaging portraits of his teenage victims. The massacre itself, along with initial interrogations and identification of the dead, takes up two long chapters totaling about 100 pages – best devoured in one big gulp when you’re feeling strong. It’s hard to read, but brilliantly rendered. Anyone with an interest in psychology or criminology will find the insights into Breivik’s personality fascinating. This is a book about love and empathy: what they can achieve; what happens when they are absent. It shows how wide the ripples of one person’s actions can be, but also how deep individual motivation goes. All wrapped up in a gripping true crime narrative. Doubtless one of the best books I will read this year.

An utterly engrossing account of Anders Behring Breivik’s July 22, 2011 attacks on an Oslo government building (8 dead) and the political youth camp on the island of Utøya (69 killed). Over half of this hefty tome is prologue: Breivik’s life story, plus occasional chapters giving engaging portraits of his teenage victims. The massacre itself, along with initial interrogations and identification of the dead, takes up two long chapters totaling about 100 pages – best devoured in one big gulp when you’re feeling strong. It’s hard to read, but brilliantly rendered. Anyone with an interest in psychology or criminology will find the insights into Breivik’s personality fascinating. This is a book about love and empathy: what they can achieve; what happens when they are absent. It shows how wide the ripples of one person’s actions can be, but also how deep individual motivation goes. All wrapped up in a gripping true crime narrative. Doubtless one of the best books I will read this year.

My rating:

Cold: Adventures in the World’s Frozen Places

By Bill Streever

“Cold is a part of day-to-day life, but we often isolate ourselves from it, hiding in overheated houses and retreating to overheated climates, all without understanding what we so eagerly avoid.” In 12 chapters spanning one year, Streever covers every topic related to the cold that you could imagine: polar exploration, temperature scales, extreme weather events (especially the School Children’s Blizzard of 1888 and the “Year without Summer,” 1815), ice ages, cryogenics technology, and on and on. There’s also a travel element, with Streever regularly recording where he is and what the temperature is, starting in his home turf of Anchorage, Alaska. My favorite chapters were February and March, about the development of refrigeration and air conditioning and cold-weather apparel, respectively.

“Cold is a part of day-to-day life, but we often isolate ourselves from it, hiding in overheated houses and retreating to overheated climates, all without understanding what we so eagerly avoid.” In 12 chapters spanning one year, Streever covers every topic related to the cold that you could imagine: polar exploration, temperature scales, extreme weather events (especially the School Children’s Blizzard of 1888 and the “Year without Summer,” 1815), ice ages, cryogenics technology, and on and on. There’s also a travel element, with Streever regularly recording where he is and what the temperature is, starting in his home turf of Anchorage, Alaska. My favorite chapters were February and March, about the development of refrigeration and air conditioning and cold-weather apparel, respectively.

My rating:

A Series of Catastrophes and Miracles

By Mary Elizabeth Williams

“SPOILER: I lived,” the Salon journalist begins her bittersweet memoir of having Stage 4 metastatic melanoma. In August 2010 she had a several-millimeter scab on her head surgically removed. When the cancer came back a year and a half later, this time in her lungs as well as on her back, she had the extreme good luck of qualifying for an immunotherapy trial that straight up cured her. It’s an encouraging story you don’t often hear in a cancer memoir. On the other hand, her father-in-law’s esophageal cancer and her best friend Debbie’s ovarian cancer simply went from bad to worse. As the title suggests, Williams’s tone vacillates between despair and hope, but her writing is always wry and conversational.

“SPOILER: I lived,” the Salon journalist begins her bittersweet memoir of having Stage 4 metastatic melanoma. In August 2010 she had a several-millimeter scab on her head surgically removed. When the cancer came back a year and a half later, this time in her lungs as well as on her back, she had the extreme good luck of qualifying for an immunotherapy trial that straight up cured her. It’s an encouraging story you don’t often hear in a cancer memoir. On the other hand, her father-in-law’s esophageal cancer and her best friend Debbie’s ovarian cancer simply went from bad to worse. As the title suggests, Williams’s tone vacillates between despair and hope, but her writing is always wry and conversational.

My rating:

(For each one, read my full Goodreads review by clicking on the title link.)