#NovNov25 Final Statistics & Some 2026 Novellas to Look Out For (Chapman, Fennelly, Gremaud, Miles, Netherclift & Saunders)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. If you want to take a look back at the link parties, they’re all here. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For those who are curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

I read and reviewed 21 novellas in November. I happen to have already read six with 2026 release dates, some of them within November and others a bit earlier for paid reviews. I’ll give a quick preview of each so you’ll know which ones you want to look out for.

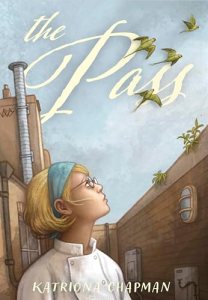

The Pass by Katriona Chapman

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

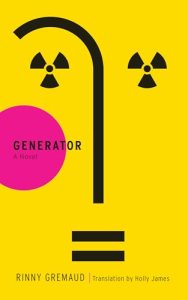

Generator by Rinny Gremaud (2023; 2026)

[Trans. from French by Holly James]

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy)

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Vessel: The shape of absent bodies by Dani Netherclift

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy)

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Vigil by George Saunders

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley)

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley) ![]()

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of  I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s

I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s  Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to

Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to  The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after

The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after  A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)  Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 (

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 ( I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels (

I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels ( The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after

The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after  This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which

This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which