Of Human Bondage: Finally Caught Up from 2015

When it came to it, it isn’t me

was all he seemed to learn

from all his diligent forays outward.

(from “It Isn’t Me” by James Lasdun)

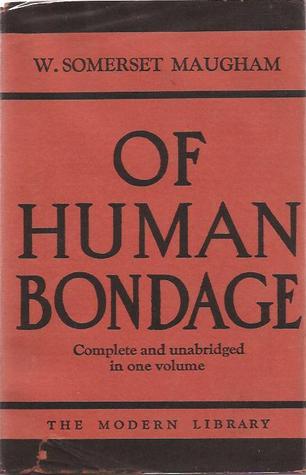

I chose to read this doorstopper from 1915 because it appeared in The Novel Cure on a list entitled “The Ten Best Novels for Thirty-Somethings.” By happy accident, I was also reading it throughout its centenary year. My knowledge of W. Somerset Maugham’s work was limited – I had seen the 2006 film version of The Painted Veil but never read anything by him – so I had no clear idea of what to expect. I was pleased to encounter a narrative rich with psychological insight and traces of the Victorian novel.

Philip Carey is not unlike a Dickensian hero: born with a club foot and orphaned as a child, he’s raised by his stern vicar uncle in Kent and reluctantly attends boarding school. Much of the book is filled with his post-schooling wanderings and professional shilly-shallying, along with multiple romantic missteps. He studies in Germany, tries to make it as a painter in Paris, and returns to London to train as an accountant and then as a doctor. Each attempted career seems to fail, as does every relationship. Philip reminded me most of David Copperfield, especially after he meets the jolly, Micawber-esque Thorpe Athelny during his hospital internship and becomes friendly with his wife and children.

Philip Carey is not unlike a Dickensian hero: born with a club foot and orphaned as a child, he’s raised by his stern vicar uncle in Kent and reluctantly attends boarding school. Much of the book is filled with his post-schooling wanderings and professional shilly-shallying, along with multiple romantic missteps. He studies in Germany, tries to make it as a painter in Paris, and returns to London to train as an accountant and then as a doctor. Each attempted career seems to fail, as does every relationship. Philip reminded me most of David Copperfield, especially after he meets the jolly, Micawber-esque Thorpe Athelny during his hospital internship and becomes friendly with his wife and children.

As is common in Victorian novels, Philip is troubled by his conflicting desires. When it comes to women, he cannot get love to match up with lust. As a youth he loses his virginity to Emily Wilkinson, a woman in her mid-30s, then wants nothing to do with her. A few other dalliances have mixed success, but the novel focuses on Philip’s connection to Mildred Rogers. A café waitress, she’s vain and ill-tempered and acts indifferent to Philip – but is happy for him to spend money on her. He’s disgusted and infatuated all at once: “He did not care if she was heartless, vicious and vulgar, stupid and grasping, he loved her. He would rather have misery with [her] than happiness with [another].” Though Mildred tries to eschew the traditional roles of wife and mother, the Victorian notion of the fallen woman haunts her.

This on-again, off-again romance forms the heart of the book. Both Philip and Mildred are maddening in their own way. Not since Pip (another Philip, interestingly) in Great Expectations have I been so furious at a main character for consistently making the wrong choices, being dazzled by beauty and status and ignoring the more important things in life. Yet the close third-person narration sees so deeply into Philip’s psyche that I could not help but feel sympathy for him, too, cringing over his every failure – especially when stock market losses leave him destitute and he undertakes humiliating (to him) work at a department store. The novel is liberally studded with intimate paragraphs conveying Philip’s thoughts:

He painted with the brain, and he could not help knowing that the only painting worth anything was done with the heart. … [H]e had a terrible fear that he would never be more than second-rate. Was it worth while for that to give up one’s youth, and the gaiety of life, and the manifold chances of being?

Pain and disease and unhappiness weighed down the scale so heavily. What did it all mean? He thought of his own life, the high hopes with which he had entered upon it, the limitations which his body forced upon him, his friendlessness, and the lack of affection which had surrounded his youth. He did not know that he had ever done anything but what seemed best to do, and what a cropper he had come! Other men, with no more advantages than he, succeeded, and others again, with many more, failed. It seemed pure chance. The rain fell alike upon the just and upon the unjust, and for nothing was there a why and a wherefore.

Another humanizing element that especially appealed to me was Philip’s loss of Christian faith. During my study abroad year and especially my master’s year at Leeds, when I wrote a dissertation on women’s loss-of-faith narratives in Victorian fiction, I read a lot of novels about belief and doubt. In Philip’s case, I was interested to see how Maugham portrays what is usually seen as a loss as more of a liberation:

Suddenly he realised that he had lost also that burden of responsibility which made every action of his life a matter of urgent consequence. He could breathe more freely in a lighter air. He was responsible only to himself for the things he did. Freedom! He was his own master at last. From old habit, unconsciously he thanked God that he no longer believed in Him.

Although Philip frequently indulges in self-pity, he also has moments where he wakes up to the wonder of life. These epiphanies of the beauty of London, of the whole world, were among my favorite scenes.

Unusually in a long book, I thought the last 150 pages were the strongest. I struggled to pay attention throughout Philip’s schooling and wearied of the endless negotiations with Mildred, but when Philip is at his lowest point – like the protagonist of Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, not even sure if he’ll find enough to eat – there’s a real intensity to the plot that made this last chunk fly by.

I read a 1930s Modern Library copy from the University of Reading, but consulted Robert Calder’s introduction to the 1992 Penguin Classics edition for background information. It seems the novel was recognizably autobiographical for Maugham, though where a club foot was Philip’s source of shame, for the author it was his stammer (and his sexuality – he married but is known to have been a homosexual).

Like Joyce’s roughly contemporary A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Calder notes, Of Human Bondage fits into the “apprentice novel” genre. Despite being published in 1915, it is set in a recent past so makes no reference to the First World War, though the Boer War plays a background role. I didn’t find the book to be particularly dated; I even discovered that a couple of sayings I might have pegged as later inventions were around in the 1910s: “like it or lump it” and “put that in your pipe and smoke it.”

Of Human Bondage met with a lukewarm critical response in its own time but does seem to be among the more beloved – if obscure – classics nowadays. Calder insists that it “remains Maugham’s most complete statement of the importance of physical and spiritual liberty.”

There have been three film versions – and another is in production this year, apparently. The best known, from 1934, launched the career of Bette Davis, who gave it her all as Mildred Rogers (she was a write-in favorite for the Oscars that year). Overacting, for sure, but her blonde wave and simpering looks were perfect for the role. By contrast, Leslie Howard’s is a fairly subtle Philip. The movie – condensed, amazingly, to just over an hour and a half – focuses on his club foot and his relationship with Mildred; I was disappointed that no attempt was made to reproduce Philip’s introspective monologues through voiceovers.

To my surprise, Calder asserts that Of Human Bondage “has become one of the most widely read of modern novels, particularly by young people, who still find relevance in Philip’s struggle for a free and meaningful life.” It was good enough for Holden Caulfield, after all. It struck me during my reading that two recent novels may have taken inspiration from Maugham: the main character in Esther Freud’s Mr. Mac and Me, set in 1914, has a club foot; and in Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life Jude’s shame over his deteriorating physical condition, especially his legs, is reminiscent of Philip’s.

I’m not sure I’ll try anything else by Maugham – how could I when there’s still so much of Dickens and Hardy left to read? – but I’m certainly glad I read this. It’s clear why Berthoud and Elderkin thought Of Human Bondage would be a perfect read for someone in their 30s: it’s infused with the protagonist’s nostalgia for his youth and regret at opportunities not taken and time lost. The novel imagines a world where, even without a god pulling a string, some misfortune seems to be fated. Even so, free will is there, allowing you to recover from failure and try something new that will be truer to yourself in this one and only life.

My rating:

Literary Tourism in Dublin

Almost immediately after our trip to Manchester (see my write-up of the literary destinations), we left again for Dublin, where my husband was attending a Royal Entomological Society conference. Like we did last year when he presented a poster at a conference in Florence, I went along since we only had to pay for my flight and meals.

We stayed north of the Liffey at one of the branches of Jurys Inn. For some reason they put us in a disabled room, which meant the bathroom was a bit odd, but I can’t complain about the breakfast buffet, which included black pudding, soda bread, fruit scones, and particularly delicious porridge.

Across the street was the terrific Chapters bookstore, with extensive secondhand and new stock. I highly recommend the Lonely Planet guide to Dublin, which provided my maps and many of my ideas for the week; I even managed to do 8 of their 10 recommended activities.

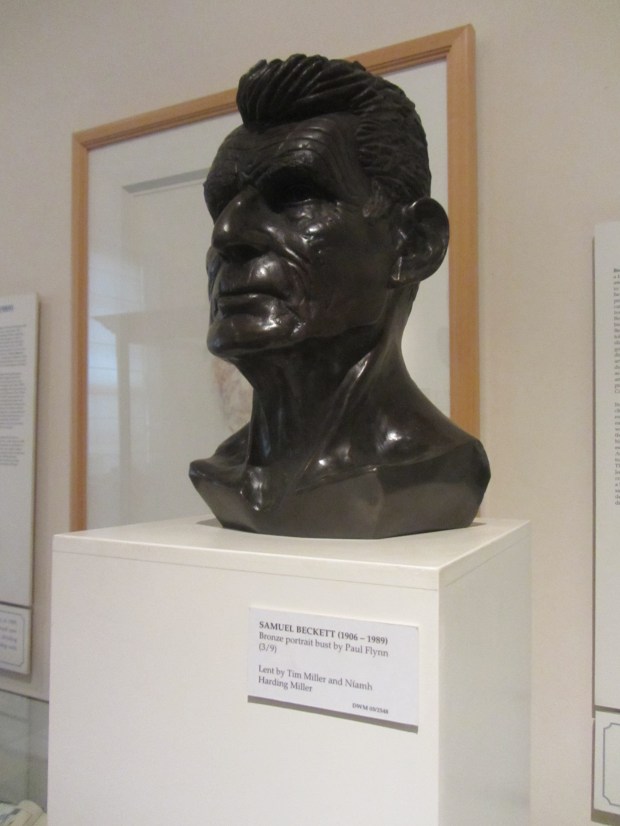

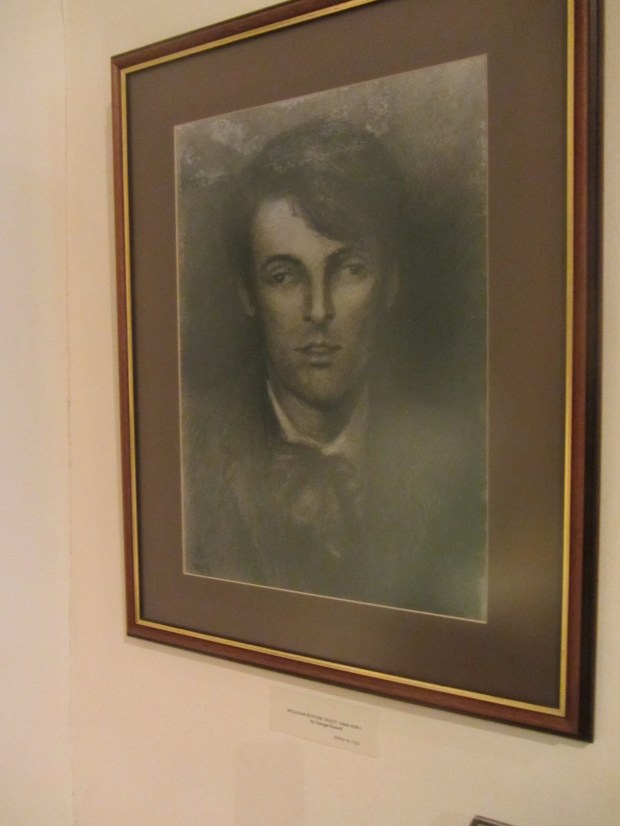

On Wednesday I wandered just a few minutes down the road to the Dublin Writers’ Museum. An audio guide takes you through the chronological displays about minor figures as well as the big names like W.B. Yeats, Oscar Wilde, and George Bernard Shaw. One caveat: only dead writers are considered; the museum is definitely missing a trick there – they could easily fill another room with living authors.

On the whole I found the place looking a bit shabby nowadays, but I passed a pleasant hour and a half here before popping a few doors down to the Dublin City Gallery, where they have multiple paintings by Jack B. Yeats (William Butler’s brother) as well as gems like a Monet and a Monet.

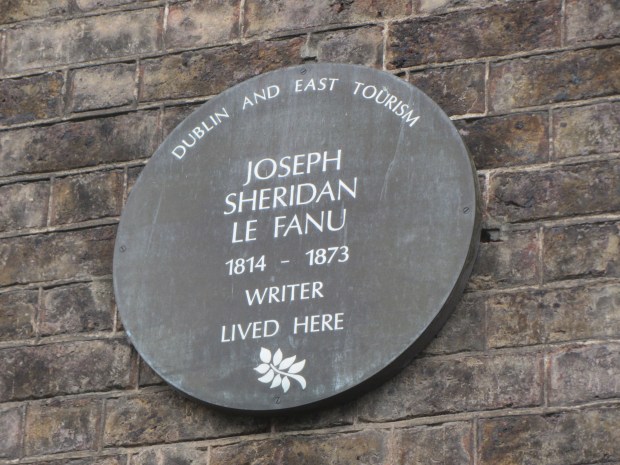

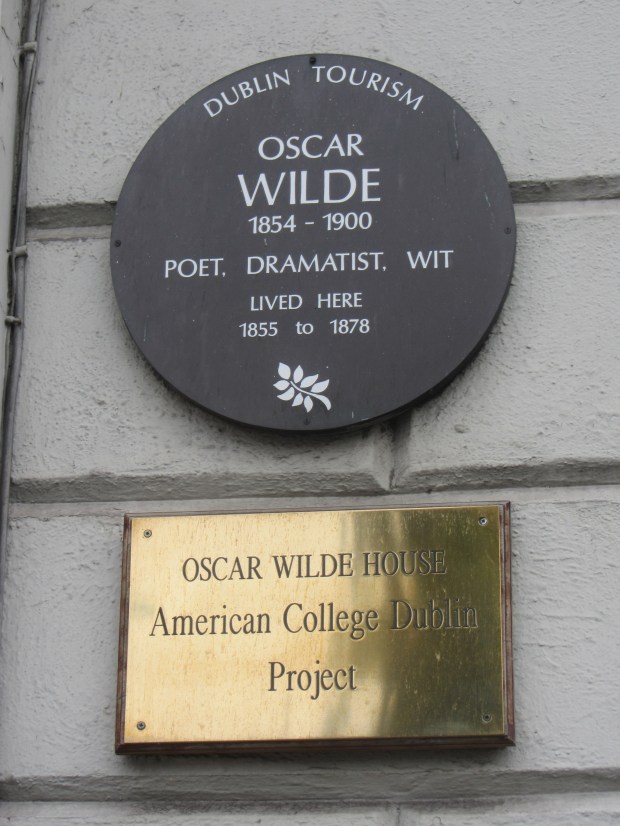

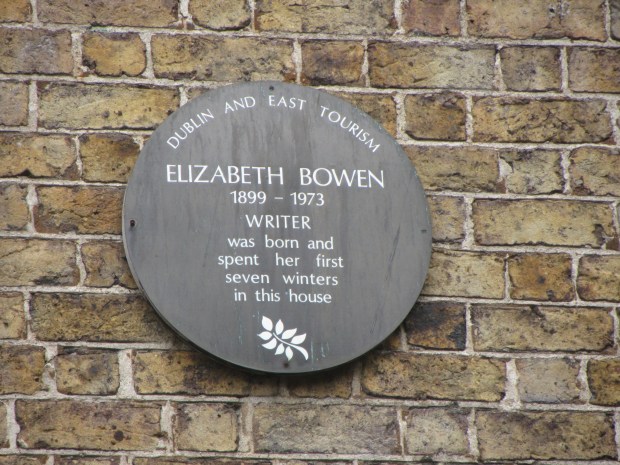

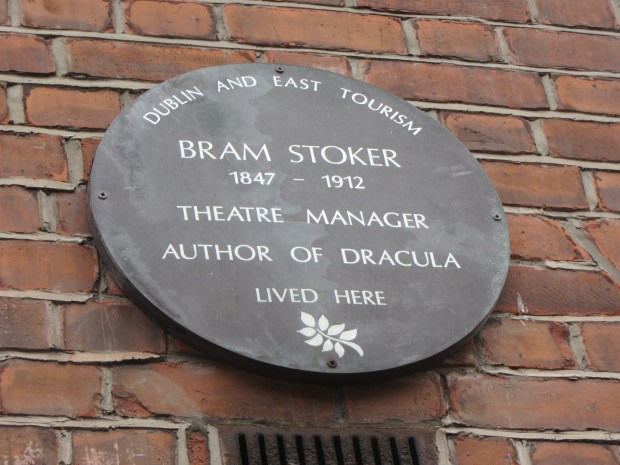

On Thursday I used the DK guide for a recommended walk through literary and Georgian Dublin. Along the way I discovered plaques to Yeats, Wilde (his home is now the headquarters of the American College and not open to the public, alas), ghost story writer Joseph Sheridan LeFanu, Bram Stoker, and Elizabeth Bowen, and a statue of poet Patrick Kavanagh by the canal. Fitzwilliam and Merrion Squares reminded me of London’s Bloomsbury Square (the latter houses a deliciously camp statue of Wilde), and St. Stephen’s Green would be a Hyde Park-type lovely spot for a sunny stroll – though it was drizzling and chilly as I walked through.

At the National Museum (Archaeology), I learned about Brian Boru, the national hero who kicked out the Vikings at the Battle of Clontarf and united the country.

My husband’s conference was at Trinity College, so he had a special chance to look in at the Old Library and the Book of Kells for a discounted price, but I didn’t end up going. On Thursday night we did something quintessentially Irish: found a pub with live traditional Irish folk music. Although we paid through the teeth for a pint of Guinness and a bottle of cider, it was an experience we wouldn’t have missed.

On Friday, after finishing up some reviewing work in the morning and checking out of the hotel, I returned to the Lonely Planet for a guided walk through Viking and medieval Dublin. The route took in the two cathedrals plus various other churches, ending up at the Castle and the Chester Beatty Library. I skipped the former but enjoyed a brief look at the rare books and manuscripts of the latter (mostly relating to the Far East, with a special focus on Asian religions) before walking back to the National Gallery to see the permanent collection.

That afternoon we moved on to Howth, a Dublin suburb only about 20 minutes away on the DART commuter train, but that somehow feels a world away: it’s a pleasant seaside village with heather- and gorse-covered hills and a lighthouse. It felt good to get out of the city – which was extremely busy and seemed to be mostly full of fellow tourists and the homeless – even if just for a little while.

This was our first Airbnb experience and turned out well after some unfortunate communication difficulties. Before settling in to our B&B we found a cheap and filling meal of fish and chips. The next day we explored the cliffs and met some friendly hooded crows before heading back into Dublin for a look at the wonderfully musty Natural History Museum and an excellent dinner at The Woollen Mills (interesting American fusion food: I had pork belly mac & cheese, and our dessert platter included an Oreo peanut butter tart).

My overall feeling was that Dublin still isn’t making as much of its literary heritage as it might do. I was perhaps not as impressed as I’d hoped to be – it’s a lot like London, and not as quaint as I might have expected. Still, I’m glad I went. Next time, though, I suspect we’ll go to less inhabited and more picturesque areas in the south and west.

I hadn’t the courage to face Joyce’s Ulysses or some other monolith of Irish literature, but I did continue Anne Enright’s The Green Road while in Dublin. I was also working on My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff, Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham (my current doorstopper), and The Heart Goes Last by Margaret Atwood.

Any comments about Ireland and its literary sites and/or heroes are most welcome!