Three on a Theme: Armchair Travels at the Italian Coast (Rachel Joyce, Sarah Moss and Jess Walter – #18 of 20 Books)

I’ve done a lot of journeying through Italy’s lakes and islands this summer. Not in real life, thank goodness – it would be far too hot! – but via books. I started with the Moss, then read the Joyce, and rounded off with the Walter, a book that had been on my TBR for 12 years and that many had heartily recommended, so I was delighted to finally experience it for myself.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce (2025)

Joyce has really upped her game. I’ve somehow read all of her books though I often found them, from Harold Fry onward, disappointingly sentimental and twee. But with this she’s entering the big leagues, moving into the more expansive, elegant and empathetic territory of novels by Anne Enright (The Green Road), Patrick Gale (Notes from an Exhibition), Maggie O’Farrell (Instructions for a Heatwave) and Tom Rachman (The Italian Teacher). It’s the story of four siblings, initially drawn together and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s death. Despite weighty themes of alcoholism, depression and marital struggles, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read.

Vic Kemp, the title figure, was a larger-than-life, womanizing painter whose work divided critics. After his first wife’s early death from cancer, he raised three daughters and a son with the help of a rotating cast of nannies (whom he inevitably slept with). At 76 he delivered the shocking news that he was marrying again: Bella-Mae, an artist in her twenties – much younger than any of his children. They moved from London to his second home in Italy just weeks before he drowned in Lake Orta. Netta, the eldest daughter, is sure there’s something fishy; he knew the lake so well and would never have gone out for a swim with a mist rolling in. Did Bella-Mae kill him for his money? And where is his last painting? Funny how waiting for an autopsy report and searching for a new will and carping with siblings over the division of belongings can ruin what should be paradise.

The interactions between Netta, Susan, Goose (Gustav) and Iris, plus Bella-Mae and her cousin Laszlo, are all flawlessly done, and through flashbacks and surges forward we learn so much about these flawed and flailing characters. The derelict villa and surrounding small town are appealing settings, and there are a lot of intriguing references to food, fashion and modern art.

My only small points of criticism are that Iris is less fleshed out than the others (and her bombshell secret felt distasteful), and that Joyce occasionally resorts to delivering some of her old obvious (though true) messages through an omniscient narrator, whereas they could be more palatable if they came out organically in dialogue or indirectly through a character’s thought process. Here’s an example: “When someone dies or disappears, we can only tell stories about what might have been the case or what might have happened next.” (One I liked better: “There were some things you never got over. No amount of thinking or talking would make them right: the best you could do was find a way to live alongside them.”) I also don’t think Goose would have been able to view his father’s body more than two months after his death; even with embalming, it would have started to decay within weeks.

You can tell that Joyce got her start in theatre because she’s so good at scenes and dialogue, and at moving people into different groups to see what they’ll do. She’s taken the best of her work in other media and brought it to bear here. It’s fascinating how Goose starts off seeming minor and eventually becomes the main POV character. And ending with a wedding (good enough for a Shakespearean comedy) offers a lovely occasion for a potential reconciliation after a (tragi)comic plot. More of this calibre, please! (Public library) ![]()

Ripeness by Sarah Moss (2025)

One sneaky little line, “Ripeness, not readiness, is all,” a Shakespeare mash-up (“Ripeness is all” is from King Lear vs. “the readiness is all” is from Hamlet), gives a clue to how to understand this novel: As a work of maturity from Sarah Moss, presenting life with all its contradictions and disappointments, not attempting to counterbalance that realism with any false optimism. What do we do, who will we be, when faced with situations for which we aren’t prepared?

Now that she’s based in Ireland, Moss seems almost to be channelling Irish authors such as Claire Keegan and Maggie O’Farrell. The line-up of themes – ballet + sisters + ambivalent motherhood + the question of immigration and belonging – should have added up to something incredible and right up my street. While Ripeness is good, even very good, it feels slightly forced. As has been true with some of Moss’s recent fiction (especially Summerwater), there is the air of a creative writing experiment. Here the trial is to determine which feels closer, a first-person rendering of a time nearly 60 years ago, or a present-tense, close-third-person account of the now. [I had in mind advice from one of Emma Darwin’s Substack posts: “What you’ll see is that ‘deep third’ is really much the same as first, in the logic of it, just with different pronouns: you are locking the narrative into a certain character’s point-of-view, but you don’t have a sense of that character as the narrator, the way you do in first person.” Except, increasingly as the novel goes on, we are compelled to think about Edith as a narrator, of her own life and others’.

In the current story line, everyone in rural West Ireland seems to have come from somewhere else (e.g. Edith’s lover Gunter is German). “She’s going to have to find a way to rise above it, this tribalism,” Edith thinks. She’s aghast at her town playing host to a small protest against immigration. Fair enough, but including this incident just seems like an excuse for some liberal handwringing (“since it’s obvious that there is enough for all, that the problem is distribution not supply, why cannot all have enough? Partly because people like Edith have too much.”). The facts of Maman being French-Israeli and having lost family in the Holocaust felt particularly shoehorned in; referencing Jewishness adds nothing. I also wondered why she set the 1960s narrative in Italy, apart from novelty and personal familiarity. (Teenage Edith’s high school Italian is improbably advanced, allowing her to translate throughout her sister’s childbirth.)

Though much of what I’ve written seems negative, I was left with an overall favourable impression. Mostly it’s that the delivery scene and the chapters that follow it are so very moving. Plus there are astute lines everywhere you look, whether on dance, motherhood, or migration. It may simply be that Moss was taking on too much at once, such that this lacks the focus of her novellas. Ultimately, I would have been happy to have just the historical story line; the repeat of the surrendering for adoption element isn’t necessary to make any point. (I was relieved, anyway, that Moss didn’t resort to the cheap trick of having the baby turn out to be a character we’ve already been introduced to.) I admire the ambition but feel Moss has yet to return to the sweet spot of her first five novels. Still, I’m a fan for life. (Public library) ![]()

#18 of my 20 Books of Summer

(Completing the second row on the Bingo card: Book set in a vacation destination)

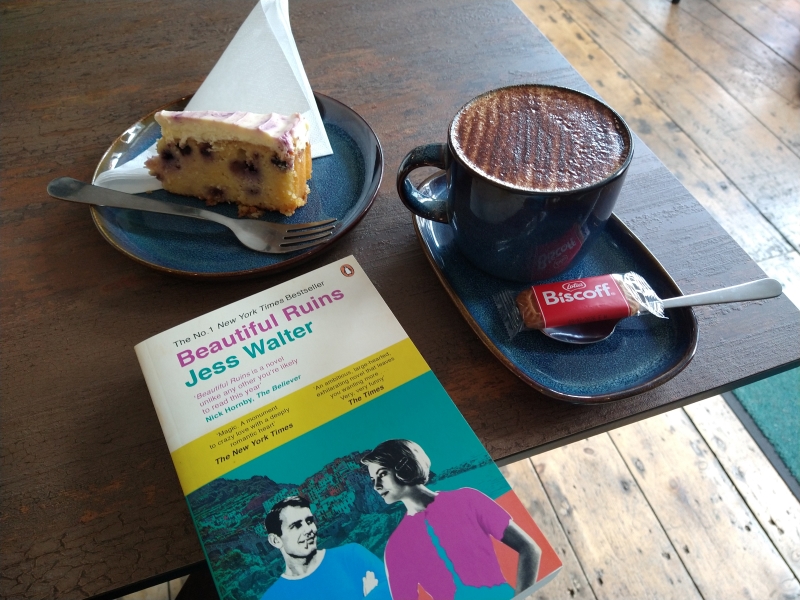

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (2012)

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I’m relieved to report that Beautiful Ruins lived up to everyone’s acclaim – and my own high expectations after enjoying Walter’s So Far Gone, which I reviewed for BookBrowse earlier in the summer. I was immediately captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. With refreshing honesty, he’s dubbed the place “Hotel Adequate View.” In April 1962, he’s attempting to build a cliff-edge tennis court when a boat delivers beautiful, dying American actress Dee Moray. It soon becomes clear that her condition is nothing nine months won’t fix and she’s been dumped here to keep her from meddling in the romance between the leads in Cleopatra, filming in Rome. In the present day, an elderly Pasquale goes to Hollywood to find out whatever happened to Dee.

A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime masterpiece, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in that summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. True to the tone of a novel about regret, failure and shattered illusions, Walter doesn’t tie everything up neatly, but he does offer a number of the characters a chance at redemption. This felt to me like a warmer and more timeless version of A Visit from the Goon Squad. There are so many great scenes, none better than Richard Burton’s drunken visit to Porto Vergogna, which had me in stitches. Fantastic. (Hungerford Bookshop – 40th birthday gift from my husband from my wish list) ![]()