Wendell Berry’s “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer” & Why I Acquired My First Smartphone at Age 40.5

Wendell Berry is an American treasure: the 89-year-old Kentucky farmer is also a philosopher, poet, theologian, and writer of fiction, and many of his pronouncements bear the timeless wisdom of a biblical prophet. I’ve read his work from several genres and was curious to see how this 1987 essay – originally published in Harper’s Magazine and reprinted, along with some letters to the editor in response, plus extra commentary in the form of a 1990 essay, by Penguin in 2018 as the 50th and final entry in their Penguin Modern pamphlet series – might resonate with my own reluctance to adopt current technology.

The title essay is brief, barely filling 4.5 pages of a small-format paperback. It’s so concise that it would be difficult to summarize in many fewer words, but I’ll run through the points he makes across the initial essay, the replies to the correspondence, and a follow-up piece entitled “Feminism, the Body and the Machine” (1989). Berry laments his reliance on energy corporations and wants to limit that as much as possible. He decries consumerism in general; he isn’t going to acquire something just to be ‘keeping up with the times’. He doesn’t believe a computer will make his work better, and it doesn’t meet his criteria for a useful tool (smaller, cheaper and less energy-intensive than what it replaces; sourced locally and easily repaired by a non-specialist). He is perfectly happy with his current arrangement: he writes his work by hand and his wife types it up for him. He is loath to lose this human touch.

The letters to the editor, predictably, accuse him of self-righteousness for depicting his choice as the more virtuous one. The correspondents also felt they had to stand up for Berry’s wife, who might have better things to do than act as her husband’s secretary. This is the only time the author becomes slightly defensive, basically saying, ‘you don’t know anything about me, my wife or my marriage … maybe she wants to!’ He doubles down on the environmental harm caused by technology and consumerism, acknowledging his continued dependence on fossil fuels and vowing to avoid them, and unnecessary purchases, where possible.

If some technology does damage to the world, … then why is it not reasonable, and indeed moral, to try to limit one’s use of that technology?

To the extent that we consume, in our present circumstances, we are guilty. To the extent that we guilty consumers are conservationists, we are absurd. … can we do something directly to solve our share of the problem? … Why then is not my first duty to reduce, so far as I can, my own consumption?

If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer one is not to use one.

He even appears to speak prophetically to the rise of artificial intelligence:

My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can. … And in our time this means that we must save ourselves from the products that we are asked to buy in order, ultimately, to replace ourselves. The danger most immediately to be feared in ‘technological progress’ is the degradation and obsolescence of the body.

Certain of his arguments felt relevant to me as I ponder my own relationship to technology. I compose all my reviews on a 19-year-old personal computer that’s not connected to the Internet. I don’t listen to the radio and have seen maybe three films in the past two years. We’ve been television-free for a decade and I have never regretted it (Berry: “It is easy – it is even a luxury – to deny oneself the use of a television set, and I zealously practice that form of self-denial. Every time I see television (at other people’s houses), I am more inclined to congratulate myself on my deprivation.”).

I find it so hard to adjust to new tech that my reluctance may have shaded into suspicion. I’m certainly no early adopter, but I’d also object to the label “Luddite”: since 2013 I’ve been using e-readers, which are invaluable in my reviewing work. But for 15 years or more I have been looking at other people and their smartphones with disdain. I prided myself on my resistance. Stubbornness seemed like a virtue when the alternative was spending a lot of money on something I didn’t need.

Receiving my first cell phone in July 2004 (with my dad at left; at Dulles airport).

Two months ago, though, I finally gave in and accepted a hand-me-down Motorola Android phone from my father-in-law, after nearly 20 years of using an old-style mobile phone. As we were renegotiating our phone and Internet contract, I got virtually unlimited minutes and data on this device for £6/month, with no initial outlay. Had I been forced to make a purchase, I think I would still be holding out. But I had gotten to the point where refusal was cutting off my nose to spite my face. Why keep martyring myself – saying I couldn’t make important household phone calls because they drained my pay-as-you-go credit; learning complex workarounds to post to Instagram from my PC; taking crap photos on a digital camera held together with a rubber band? Why resist utility just for the sake of it?

To be clear, this was not a matter of saving time. I’m not a busy person. Plus I believe there is value in slowing down and acting deliberately. (See this book-based article I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2018 on the benefits of “wasting time.”) Mindless scrolling is as much a temptation on a PC as on a phone, so avoiding social media was not a motive for me; others with addictive tendencies may decide otherwise. Nor did I view convenience as reason enough per se. However, I admit I was attracted to the efficiency of a pocket-sized device that can at once replace a computer, pager, telephone, Rolodex, phonebook, camera, photo album, television screen, music player, camcorder, Dictaphone, stopwatch, calculator, map, satnav, flashlight, encyclopaedia, Kindle library, calendar, diary, Post-It notes, notebook, alarm clock and mirror. (Have I missed anything?) Talk about multi-tasking!

Out with the old, in with the new?

I would still say that I object to tech serving as a status symbol or a basis for self-importance, and I’d be pretty dubious about it ever being a worthwhile hobby. Should this phone fail me in future, I’ll copy my husband’s habit of buying a secondhand handset for £60–80. I wouldn’t acquire something that represented new extraction of rare resources. Treating things (or people) as disposable is anathema to me, something about which I know Berry would agree. I’m naturally parsimonious, obsessive about keeping things going for as long as possible and recycling them responsibly when they reach their end of life.

It’s one reason why I’ve gotten involved in the Repair Café movement. I volunteer for our local branch, which started up in February, on the admin and publicity side of things. The old-fashioned, make-do-and-mend ethos appeals to me. It’s the same spirit evoked in the lyrics of American singer-songwriter Mark Erelli’s “Analog Hero”:

He’s the fix-it man, the fix-it man

If he can’t put it back together, then it was never worth a damn

Maybe he’s crazy for trying to save what’s already gone

Now it ain’t even broken and we’re going for the upgrade

Nobody thinks twice ’bout what we’re really throwing away

It’s out with the old, in with the new…

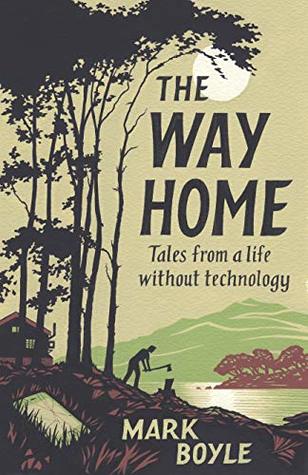

I can imagine Wendell Berry still pecking out his words on a typewriter on his Kentucky farm. He’s an analogue hero, too. And he doesn’t go nearly as far as Mark Boyle, whose radical life experiment is recounted in The Way Home: Tales from a life without technology, which I reviewed for Shiny New Books in 2019.

I have pretty much made my peace with owning a smartphone. I have few apps and am still more likely to work at my PC or on paper. I’ll concede that I enjoy being able to post to X or Instagram wherever I am, and to keep up with messages on the go. (I used to have to say cryptic things to friends like, “once I leave the house, I will be unavailable except by text.”) Mostly, I’m relieved to have shed the frustrations of outmoded tech. Though I still keep my Nokia brick by my bedside as a trusty alarm clock – and a torch for when the cat wakes me between 2 and 5 each morning.

Ultimately, I feel, a smartphone is a tool like any other. It’s how you use it. Salman Rushdie comes to much the same conclusion about the would-be murder weapon wielded against him: “a knife is a tool, and acquires meaning from the use we make of it. It is morally neutral” (from Knife).

Berry’s argument about overreliance on energy remains a good one, but we are all so complicit in so many ways – even more so than in the late 1980s when he was writing – that avoiding the computer, and now the smartphone, doesn’t seem to hold particular merit. While this pamphlet will be but a quaint curio piece for most readers (rather than a parallel to the battle of wills I’ve conducted with myself), it is engaging and convincing, and the societal issues it considers are still ones to be wrestled with.

My copy was purchased with part of a £30 voucher I received free from Penguin UK for being part of their “Bookmarks” online community – answering polls, surveys, etc.

Too Male! (A Few Recent Reviews for Shiny New Books and TLS)

I tend to wear my feminism lightly; you won’t ever hear me railing about the patriarchy or the male gaze. But there have been five reads so far this year that had me shaking my head and muttering, “too male!” While aspects of these books were interesting, the macho attitude or near-complete dearth of women irked me. Two of them I’ve already written about here: Ernest Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden was a previous month’s classic and book club selection, while Chip Cheek’s Cape May was part of my reading in America. The other three I reviewed for Shiny New Books or the Times Literary Supplement; I give excerpts below, with links to visit the full reviews in two cases, plus ideas for a book or two by a woman that should help neutralize the bad taste these might leave.

Shiny New Books

The Way Home: Tales from a Life without Technology by Mark Boyle

Boyle lives without electricity in a wooden cabin on a smallholding in County Galway, Ireland. He speaks of technology as an addiction and letting go of it as a detoxification process. For him it was a gradual shift that took place at the same time as he was moving away from modern conveniences. The Way Home is split into seasonal sections in which the author’s past and present intermingle. The writing consciously echoes Henry David Thoreau’s. Without even considering the privilege that got Boyle to the point where he could undertake this experiment, though, there are a couple of problems with this particular back-to-nature model. One is that it is a very male enterprise. Another is that Boyle doesn’t really have the literary chops to add much to the canon. Few of us could do what he has done, whether because of medical challenges, a lack of hands-on skills or family commitments. Still, the book is worth engaging with. It forces you to question your reliance on technology and ask whether making life easier is really a valuable goal.

Boyle lives without electricity in a wooden cabin on a smallholding in County Galway, Ireland. He speaks of technology as an addiction and letting go of it as a detoxification process. For him it was a gradual shift that took place at the same time as he was moving away from modern conveniences. The Way Home is split into seasonal sections in which the author’s past and present intermingle. The writing consciously echoes Henry David Thoreau’s. Without even considering the privilege that got Boyle to the point where he could undertake this experiment, though, there are a couple of problems with this particular back-to-nature model. One is that it is a very male enterprise. Another is that Boyle doesn’t really have the literary chops to add much to the canon. Few of us could do what he has done, whether because of medical challenges, a lack of hands-on skills or family commitments. Still, the book is worth engaging with. It forces you to question your reliance on technology and ask whether making life easier is really a valuable goal.

The Remedy: Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies, which I’m currently reading for a TLS review. Davies crosses Boyle’s Thoreauvian language about solitude and a place in nature with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during the ongoing housing crisis, she moves into the shed near Land’s End that once served as her father’s architecture office and embarks on turning it into a home.

The Remedy: Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies, which I’m currently reading for a TLS review. Davies crosses Boyle’s Thoreauvian language about solitude and a place in nature with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during the ongoing housing crisis, she moves into the shed near Land’s End that once served as her father’s architecture office and embarks on turning it into a home.

Doggerland by Ben Smith

This debut novel has just two main characters: ‘the old man’ and ‘the boy’ (who’s not really a boy anymore), who are stationed on an enormous offshore wind farm. The distance from the present day is indicated in slyly throwaway comments like “The boy didn’t know what potatoes were.” Smith poses questions about responsibility and sacrifice, and comments on modern addictions and a culture of disposability. He has certainly captured something of the British literary zeitgeist. From page to page, though, Doggerland grew tiresome for me. There is a lot of maritime vocabulary and technical detail about supplies and maintenance. The location is vague and claustrophobic, the pace is usually slow, and there are repetitive scenes and few conversations. To an extent, this comes with the territory. But it cannot be ignored that this is an entirely male world. Fans of the themes and style of The Old Man and the Sea and The Road will get on best with Smith’s writing. I most appreciated the moments of Beckettian humor in the dialogue and the poetic interludes that represent human history as a blip in the grand scheme of things.

This debut novel has just two main characters: ‘the old man’ and ‘the boy’ (who’s not really a boy anymore), who are stationed on an enormous offshore wind farm. The distance from the present day is indicated in slyly throwaway comments like “The boy didn’t know what potatoes were.” Smith poses questions about responsibility and sacrifice, and comments on modern addictions and a culture of disposability. He has certainly captured something of the British literary zeitgeist. From page to page, though, Doggerland grew tiresome for me. There is a lot of maritime vocabulary and technical detail about supplies and maintenance. The location is vague and claustrophobic, the pace is usually slow, and there are repetitive scenes and few conversations. To an extent, this comes with the territory. But it cannot be ignored that this is an entirely male world. Fans of the themes and style of The Old Man and the Sea and The Road will get on best with Smith’s writing. I most appreciated the moments of Beckettian humor in the dialogue and the poetic interludes that represent human history as a blip in the grand scheme of things.

The Remedy: I’m not a big fan of dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction in general, but a couple of the best such novels that I’ve read by women are Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins.

The Remedy: I’m not a big fan of dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction in general, but a couple of the best such novels that I’ve read by women are Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins.

Times Literary Supplement

The Knife’s Edge: The Heart and Mind of a Cardiac Surgeon by Stephen Westaby

In this somewhat tepid follow-up to Fragile Lives, Westaby’s bravado leaves a bad taste and dilutes the work’s ostensibly confessional nature. He has a good excuse, he argues: a head injury incurred while playing rugby in medical school transformed him into a risk taker. It’s widely accepted that such boldness may be a boon in a discipline that requires quick thinking and decisive action. So perhaps it’s no great problem to have a psychopath as your surgeon. But how about a sexist? Westaby’s persistent references to women staff as “lady GP” and “registrar lady” don’t mitigate surgeons’ macho reputation. It’s a shame to observe such casual sexism, because it’s clear Westaby felt deeply for his patients of any gender. And yet any talk of empathy earns his derision. It seems the specific language of compassion is a roadblock for him. The book is strongest when the author recreates dramatic sequences based on several risky surgeries. Alas, at its close he sounds bitter, and the NHS bears the brunt of his anger. Compared to Fragile Lives, one of my favorite books of 2017, this gives the superhero surgeon feet of clay. But it’s a lot less pleasing to read. (Forthcoming in TLS.)

In this somewhat tepid follow-up to Fragile Lives, Westaby’s bravado leaves a bad taste and dilutes the work’s ostensibly confessional nature. He has a good excuse, he argues: a head injury incurred while playing rugby in medical school transformed him into a risk taker. It’s widely accepted that such boldness may be a boon in a discipline that requires quick thinking and decisive action. So perhaps it’s no great problem to have a psychopath as your surgeon. But how about a sexist? Westaby’s persistent references to women staff as “lady GP” and “registrar lady” don’t mitigate surgeons’ macho reputation. It’s a shame to observe such casual sexism, because it’s clear Westaby felt deeply for his patients of any gender. And yet any talk of empathy earns his derision. It seems the specific language of compassion is a roadblock for him. The book is strongest when the author recreates dramatic sequences based on several risky surgeries. Alas, at its close he sounds bitter, and the NHS bears the brunt of his anger. Compared to Fragile Lives, one of my favorite books of 2017, this gives the superhero surgeon feet of clay. But it’s a lot less pleasing to read. (Forthcoming in TLS.)

The Remedy: I’m keen to read Direct Red by Gabriel Weston, a memoir by a female surgeon.

The Remedy: I’m keen to read Direct Red by Gabriel Weston, a memoir by a female surgeon.

(Crikey! This was my 600th blog post.)