Winter Reading, Part II: “Snow” Books by Coleman, Rice & Whittell

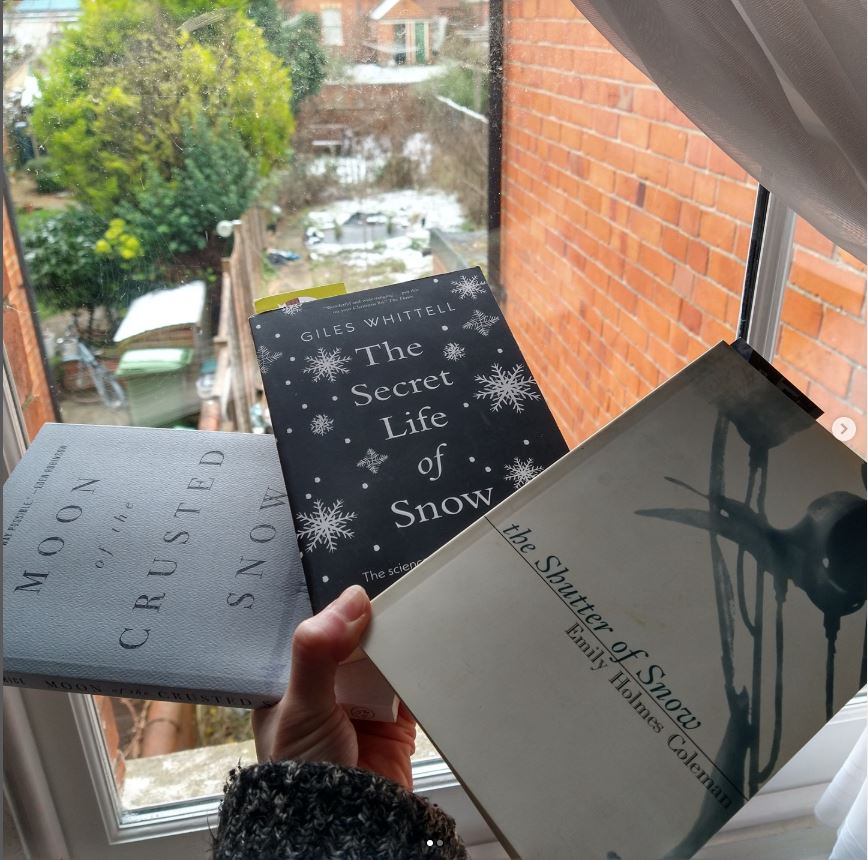

Here I am squeaking in on the day before the spring equinox – when it’s predicted to be warmer than Ibiza here in southern England, as headlines have it – with a few snowy reads that have been on my stack for much of the winter. I started reading this trio when we got a dusting back in January, in case (as proved to be true) it was our only snow of the year. I have an arresting work of autofiction that recreates a period of postpartum psychosis, a mildly dystopian novel by a First Nations Canadian, and a snow-lover’s compendium of science and trivia.

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

Snow had an unreality to it. Was this because of its pace or its beauty? There was an accompanying clarity to snow as well, especially snow, drifting snow. What was and wasn’t important were made distinct. Certain facts became chillingly apparent. Pain, for one.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman (1930)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (2018)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) ![]()

The Secret Life of Snow: The science and the stories behind nature’s greatest wonder by Giles Whittell (2018)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Whittell’s mention of the U.S. East Coast “Snowmaggedon” of February 2010 had me digging out photos my mother sent me of the aftermath at our family home of the time.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately? Or is it looking like spring?

Three on a Theme: Frost Fairs Books

Here in southern England, we’ve just had a couple of weeks of hard frost. The local canal froze over for a time; the other day when I thought it had all thawed, a pair of mallard ducks surprised me by appearing to walk on water. In previous centuries, the entire Thames has been known to freeze through central London. (I’d like to revisit Virginia Woolf’s Orlando for a 17th-century scene of that.) This thematic trio of a children’s book, a historical novel, and a poetry collection came together rather by accident: I already had the poetry collection on my shelf, then saw frost fairs referenced in the blurb of the novel, and later spotted the third book while shelving in the children’s section of the library.

A Night at the Frost Fair by Emma Carroll (2021)

Maya’s mum is visiting family in India; Maya and her dad and sister have just settled Gran into a clinical care home. Christmas is coming, and Gran handed out peculiarly mismatched presents: Maya’s older sister got a lovely brooch, while her own present was a weird brick-shaped brown object Gran says belonged to “Edmund”. Now the family is in a taxi home, crossing London Bridge, when Maya notices snow falling faster than seems possible and finds herself on a busy street of horse-drawn carriages, overlooking booths and hordes of people on the frozen river.

Maya’s mum is visiting family in India; Maya and her dad and sister have just settled Gran into a clinical care home. Christmas is coming, and Gran handed out peculiarly mismatched presents: Maya’s older sister got a lovely brooch, while her own present was a weird brick-shaped brown object Gran says belonged to “Edmund”. Now the family is in a taxi home, crossing London Bridge, when Maya notices snow falling faster than seems possible and finds herself on a busy street of horse-drawn carriages, overlooking booths and hordes of people on the frozen river.

A sickly little boy named Eddie is her tour guide to the games, rides and snacks on offer here in 1788, but there’s a man around who wants to keep him from enjoying the fair. Maya hopes to help Eddie, and Gran, all while figuring out what the gift parcel means. A low page count meant this felt pretty thin, with everything wrapped up too soon. The problem, really, was that – believe it or not – this isn’t the first middle-grade time-slip historical fantasy novel about frost fairs that I’ve read; the other, Frost by Holly Webb, was better. Sam Usher’s Quentin Blake-like illustrations are a bonus, though. (Public library)

The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (2022)

This has been catalogued as science fiction by my library system, but I’d be more likely to describe it as historical fiction with a touch of magic realism, similar to The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock or Things in Jars. I loved the way the action is bookended by the frost fairs of 1789 and 1814. There’s a whiff of the fairy tale in the setup: when we meet Neva, she’s a little girl whose parents operate one of the fair’s attractions, a chess-playing bear. She knows, like no one else seems to, that the ice is shifting and it’s not safe to stay by the Thames. When the predicted tragedy comes, she’s left an orphan and adopted by Victor Friezland, a clockmaker who shares her Russian heritage. He lives in a wonderfully peculiar house made out of ship parts and, between him, Neva, the housekeeper Elise, and other servants, friends and neighbours, they form a delightful makeshift family.

Neva predicts the weather faultlessly, even years ahead. It’s somewhere between synaesthetic and mystical, this ability to hear the ice speaking and see what the clouds hold. While others in their London circle engage in early meteorological prediction, her talent is different. Victor decides to harness it as an attraction, developing “The Weather Woman” as first an automaton and then a magic lantern show, both with Neva behind the scenes giving unerring forecasts. At the same time, Neva brings her childhood imaginary friend to life, dressing in men’s clothing and appearing as Victor’s business partner, Eugene Jonas, in public.

These various disguises are presented as the only way that a woman could be taken seriously in the early 19th century. Gardner is careful to note that Neva does not believe she is, or seek to become, a man; “She thinks she’s been born into the wrong time, not necessarily the wrong sex. As for her mind, that belongs to a different world altogether.” (Whereas there is a trans character and a couple of queer ones; it would also have been interesting for Gardner to take further the male lead’s attraction to Eugene Jonas.) From her early teens on, she’s declared that she doesn’t intend to marry or have children, but in what I suspect is a trope of romance fiction, she changes her tune when she meets the right man. This was slightly disappointing, yet just one of several satisfying matches made over the course of this rollicking story.

London charms here despite its Dickensian (avant la lettre) grime – mudlarks and body snatchers, gambling and trickery, gloomy pubs and shipwrecks, weaselly lawyers and high-society soirees. The plot moves quickly and holds a lot of surprises and diverting secondary characters. While the novel could have done with some trimming – something I’d probably say about the majority of 450-pagers – I remained hooked and found it fun and racy. You’ll want to stick around for a terrific late set-piece on the ice. Gardner had a career in theatre costume design before writing children’s books. I’ll also try her teen novel, I, Coriander. (Public library)

[Two potential anachronisms: “Hold your horses” (p. 202) and calling someone “a card” (p. 209) – both slang uses that more likely date from the 1830s or 1840s.]

The Frost Fairs by John McCullough (2010)

I knew McCullough’s name from his superb 2019 collection Reckless Paper Birds, which was shortlisted for a Costa Prize. This was his debut collection, for which he won a Polari Prize. Appropriately, one poem, “Georgie, Belladonna, Sid,” is crammed full of “Polari words” – “the English homosexual and theatrical slang prevalent in the early to mid 20th century.” The book leans heavily on historical scenes and seaside scenery. “The Other Side of Winter” is the source of the title and the cover image:

I knew McCullough’s name from his superb 2019 collection Reckless Paper Birds, which was shortlisted for a Costa Prize. This was his debut collection, for which he won a Polari Prize. Appropriately, one poem, “Georgie, Belladonna, Sid,” is crammed full of “Polari words” – “the English homosexual and theatrical slang prevalent in the early to mid 20th century.” The book leans heavily on historical scenes and seaside scenery. “The Other Side of Winter” is the source of the title and the cover image:

Overnight the Thames begins to move again.

The ice beneath the frost fair cracks. Tents,

merry-go-rounds and bookstalls glide about

On islands given up for lost. They race,

switch places, touch—the printing press nuzzling

the swings—then part, slip quietly under.

I also liked the wordplay of “The Dictionary Man,” the alliteration and English summer setting of “Miss Fothergill Observes a Snail,” and the sibilance versus jarringly violent imagery of “Severance.” However, it was hard to detect links that would create overall cohesion in the book. (Purchased directly from Salt Publishing)

A Few Bizarre Backlist Reads: McEwan, Michaels & Tremain

I’ve grouped these three prize-winning novels from the late 1980s and 1990s together because they all left me scratching my head, wondering whether they were jumbles of random elements and events or if there was indeed a satisfyingly coherent story. While there were aspects I admired, there were also moments when I thought it indulgent of the authors to pursue poetic prose or plot tangents and not consider the reader’s limited patience. I had to think for ages about how to rate these, but eventually arrived at the same rating for each, reflecting my enjoyment but also my hesitation.

The Child in Time by Ian McEwan (1987)

[Whitbread Prize for Fiction (now Costa Novel Award)]

This is the second-earliest of the 13 McEwan books I’ve read. It’s something of a strange muddle (from the protagonist’s hobbies of Arabic and tennis lessons plus drinking onwards), yet everything clusters around the title’s announced themes of children and time.

This is the second-earliest of the 13 McEwan books I’ve read. It’s something of a strange muddle (from the protagonist’s hobbies of Arabic and tennis lessons plus drinking onwards), yet everything clusters around the title’s announced themes of children and time.

Stephen Lewis’s three-year-old daughter, Kate, was abducted from a supermarket three years ago. The incident is recalled early in the book, as if the remainder will be about solving the mystery of what happened to Kate. But such is not the case. Her disappearance is an unalterable fact of Stephen’s life that drove him and his wife apart, but apart from one excruciating scene later in the book when he mistakes a little girl on a school playground for Kate and interrogates the principal about her, the missing child is just subtext.

Instead, the tokens of childhood are political and fanciful. Stephen, a writer whose novels accidentally got categorized as children’s books, is on a government committee producing a report on childcare. On a visit to Suffolk, he learns that his publisher, Charles Darke, who later became an MP, has reverted to childhood, wearing shorts and serving lemonade up in a treehouse.

Meanwhile, Charles’s wife, Thelma, is a physicist researching the nature of time. For Charles, returning to childhood is a way of recapturing timelessness. There’s also an odd shared memory that Stephen and his mother had four decades apart. Even tiny details add on to the time theme, like Stephen’s parents meeting when his father returned a defective clock to the department store where his mother worked.

This is McEwan, so you know there’s going to be a contrived but very funny scene. Here that comes in Chapter 5, when Stephen is behind a flipped lorry and goes to help the driver. He agrees to take down a series of (increasingly outrageous) dictated letters but gets exasperated at about the same time it becomes clear the young man is not approaching death. Instead, he helps him out of the cab and they celebrate by drinking two bottles of champagne. This doesn’t seem to have much bearing on the rest of the book, but is the scene I’m most likely to remember.

Other noteworthy elements: Stephen has a couple of run-ins with the Prime Minister; though this is clearly Margaret Thatcher, McEwan takes pains to neither name nor so much as reveal the gender of the PM (in fear of libel claims?). Homeless people and gypsies show up multiple times, making Stephen uncomfortable but also drawing his attention. I assumed this was a political point about Thatcher’s influence, with the homeless serving as additional stand-ins for children in a paternalistic society, representing vulnerability and (misplaced) trust.

This is a book club read for our third monthly Zoom meeting, coming up in the first week of June. While it’s odd and not entirely successful, I think it should give us a lot to talk about: the good and bad aspects of reverting to childhood, whether it matters if Kate ever comes back, the caginess about Thatcher, and so on.

Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels (1996)

[Orange Prize (now Women’s Prize for Fiction)]

“One can look deeply for meaning or one can invent it.”

Poland, Greece, Canada; geology, poetry, meteorology. At times it felt like Michaels had picked her settings and topics out of a hat and flung them together. Especially in the early pages, the dreamy prose is so close to poetry that I had trouble figuring out what was actually happening, but gradually I was drawn into the story of Jakob Beer, a Jewish boy rescued like a bog body or golem from the ruins of his Polish village. Raised on a Greek island and in Toronto by his adoptive father, a geologist named Athos who’s determined to combat the Nazi falsifying of archaeological history, Jakob becomes a poet and translator. Though he marries twice, he remains a lonely genius haunted by the loss of his whole family – especially his sister, Bella, who played the piano. Survivor’s guilt never goes away. “To survive was to escape fate. But if you escape your fate, whose life do you then step into?”

Poland, Greece, Canada; geology, poetry, meteorology. At times it felt like Michaels had picked her settings and topics out of a hat and flung them together. Especially in the early pages, the dreamy prose is so close to poetry that I had trouble figuring out what was actually happening, but gradually I was drawn into the story of Jakob Beer, a Jewish boy rescued like a bog body or golem from the ruins of his Polish village. Raised on a Greek island and in Toronto by his adoptive father, a geologist named Athos who’s determined to combat the Nazi falsifying of archaeological history, Jakob becomes a poet and translator. Though he marries twice, he remains a lonely genius haunted by the loss of his whole family – especially his sister, Bella, who played the piano. Survivor’s guilt never goes away. “To survive was to escape fate. But if you escape your fate, whose life do you then step into?”

The final third of the novel, set after Jakob’s death, shifts into another first-person voice. Ben is a student of literature and meteorological history. His parents are concentration camp survivors, so he relates to the themes of loss and longing in Jakob’s poetry. Taking a break from his troubled marriage, Ben offers to go back to the Greek island where Jakob last lived to retrieve his notebooks – which presumably contain all that’s come before. Ben often addresses Jakob directly in the second person, as if to reassure him that he has been remembered. Ultimately, I wasn’t sure what this section was meant to add, but Ben’s narration is more fluent than Jakob’s, so it was at least pleasant to read.

Although this is undoubtedly overwritten in places, too often resorting to weighty one-liners, I found myself entranced by the stylish writing most of the time. I particularly enjoyed the puns, palindromes and rhyming slang that Jakob shares with Athos while learning English, and with his first wife. If I could change one thing, I would boost the presence of the female characters. I was reminded of other books I’ve read about the interpretation of history and memory, Everything Is Illuminated and Moon Tiger, as well as of other works by Canadian women, A Student of Weather and Fall on Your Knees. This won’t be a book for everyone, but if you’ve enjoyed one or more of my readalikes, you might consider giving it a try.

Sacred Country by Rose Tremain (1992)

[James Tait Black Memorial Prize, Prix Fémina Etranger]

In 1952, on the day a two-minute silence is held for the dead king, six-year-old Mary Ward has a distinct thought: “I am not Mary. That is a mistake. I am not a girl. I’m a boy.” Growing up on a Suffolk farm with a violent father and a mentally ill mother, Mary asks to be called Martin and binds her breasts with bandages. Kicked out at age 15, she lives with her retired teacher and then starts to pursue a life on her own terms in London. While working for a literary magazine and dating women, she consults a doctor and psychologist to explore the hormonal and surgical options for becoming the man she believes she’s always been.

Meanwhile, a hometown acquaintance with whom she once shared a dentist’s waiting room, Walter Loomis, gives up his family’s butcher shop to pursue his passion for country music. Both he and Mary/Martin are sexually fluid and, dissatisfied with the existence they were born into, resolve to search for something more. The outsiders’ journeys take them to Tennessee, of all places. But when Martin joins Walter there, it’s an anticlimax. You’d expect their new lives to dovetail together, but instead they remain separate strivers.

At a bare summary, this seems like a simple plot, but Tremain complicates it with many minor characters and subplots. The story line stretches to 1980: nearly three decades’ worth of historical and social upheaval. The third person narration shifts perspective often to show a whole breadth of experience in this small English village, while occasional first-person passages from Mary and from her mother, Estelle, who’s in and out of a mental hospital, lend intimacy. Otherwise, the minor characters feel flat, more like symbols or mouthpieces.

To give a flavor of the book’s many random elements, here’s a decoding of the extraordinary cover on the copy I picked up from the free bookshop:

Crimson background and oval shape = female anatomy, menstruation

Central figure in a medieval painting style, with royal blue cloth = Mary

Masculine muscle structure plus yin-yang at top = blended sexuality

Airplane = Estelle’s mother died in a glider accident

Confederate flag = Tennessee

Cards = fate/chance, conjuring tricks Mary learns at school, fortune teller Walter visits

Cleaver = the Loomis butcher shop

Cricket bat = Edward Harker’s woodcraft; he employs and then marries Estelle’s friend Irene

Guitar = Walter’s country music ambitions

Oyster shell with pearl = Irene’s daughter Pearl, whom young Mary loves so much she takes her (then a baby) in to school for show-and-tell

Cutout torso = the search for the title land (both inward and outer), a place beyond duality

Tremain must have been ahead of the times in writing a trans character. She acknowledged that the premise was inspired by Conundrum by Jan Morris (who, born James, knew he was really a girl from the age of five). I recall that Sacred Country turned up often in the footnotes of Tremain’s recent memoir, Rosie, so I expect it has little autobiographical resonances and is a work she’s particularly proud of. I read this in advance of writing a profile of Tremain for Bookmarks magazine. It feels very different from her other books I’ve read; while it’s not as straightforwardly readable as The Road Home, I’d call it my second favorite from her. The writing is somewhat reminiscent of Kate Atkinson, early A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay, and it’s a memorable exploration of hidden identity and the parts of life that remain a mystery.