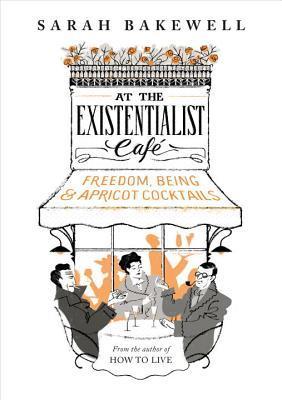

At the Existentialist Café by Sarah Bakewell

I’ve long meant to read Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live, a biography of Montaigne that also promises to be a deep examination of philosophical and ethical issues. When I heard she had a new book out, I jumped at the chance to learn more about existentialism. I’ve come away from At the Existentialist Café with only a nebulous sense of what existentialism actually means (though Bakewell’s bullet-pointed list of points towards a definition on page 34 is helpful), but certainly with more knowledge about and appreciation for Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, two of her main subjects. This is appropriate given the shift in Bakewell’s thinking: “When I first read Sartre and Heidegger, I didn’t think the details of a philosopher’s personality or biography were important. … Thirty years later, I have come to the opposite conclusion. Ideas are interesting, but people are vastly more so.”

I’ve long meant to read Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live, a biography of Montaigne that also promises to be a deep examination of philosophical and ethical issues. When I heard she had a new book out, I jumped at the chance to learn more about existentialism. I’ve come away from At the Existentialist Café with only a nebulous sense of what existentialism actually means (though Bakewell’s bullet-pointed list of points towards a definition on page 34 is helpful), but certainly with more knowledge about and appreciation for Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, two of her main subjects. This is appropriate given the shift in Bakewell’s thinking: “When I first read Sartre and Heidegger, I didn’t think the details of a philosopher’s personality or biography were important. … Thirty years later, I have come to the opposite conclusion. Ideas are interesting, but people are vastly more so.”

Some of the interesting characters herein, apart from Sartre and de Beauvoir (always referred to in these pages as “Beauvoir,” which irked me unduly), are Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Hannah Arendt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Albert Camus. It’s a large cast; you may well find yourself flipping back and forth to the helpful who’s who list in the back of the book. I was amused to see that Freiburg, Germany is the seat of phenomenology (which gave rise to existentialism) – I’m heading there in June to stay with friends at the start of a mini European tour. Husserl was the chair of philosophy at Freiburg, and Heidegger his colleague.

The best I can make out, Heidegger’s philosophy was about describing experience to get to the heart of things. Disregard peripherals and focus on the self’s knowledge of the world, he advised. His best known work, Being and Time, contrasted individual beings with Being itself (i.e. ontology). Think of him as an experimental, modernist novelist, Bakewell advises; understanding what he’s doing with his philosophy is difficult otherwise. Existentialism built on this framework but emphasized freedom and how it is exercised in particular situations.

World War II, especially the year 1945, was a turning point for many of the philosophers discussed. Sartre was held in a POW camp but his eye troubles gave him a way out. Many left Europe for America due to anti-Semitism, including Hannah Arendt and Bruno Bettelheim. Although Heidegger contrasted “the they” (das Man – more similar, perhaps, to the English phrase “the Man”) with the voice of conscience in such a way that suggested one should resist totalitarianism, he would later be exposed as a Nazi. In the following years, the United States became very popular culturally: jazz music, film noir, Hemingway. At the same time, the French were shocked at America’s racial inequality. Sartre believed that one should always take the opinion of the “least favored” or most oppressed party in any situation, which would lead him to speak out for minorities and the colonized, as in the Algerian liberation movement of the 1950s–60s. In the meantime, the rise of the Soviet Union and the development of the atom bomb would emerge as imminent societal threats.

Sartre and de Beauvoir had an open relationship but clearly relied on and felt deeply about each other, especially when it came to their writing. Bakewell convinced me of Sartre’s surprising sex appeal, despite his unprepossessing appearance: “down-turned grouper lips, a dented complexion, prominent ears, and eyes that pointed in different directions.” Apparently he had a silly side and would even do Donald Duck impressions. At the same time, he had rock-solid convictions, as evidenced by his refusal of the Légion d’Honneur and the Nobel Prize. I also learned that he was a biographer of Jean Genet and Gustave Flaubert; his biography of the latter, in three volumes, stretched to 2800 pages! Bakewell waxes anti-lyrical in her account of the disheartening experience of reading it: “Occasional lightning flashes strike the primordial soup, although they never quite spark it into life, and there is no way to find them except by dredging through the bog for as long as you can stand it.”

From the title and subtitle (“Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails”), I expected this book to be a bit more of a jolly narrative than it was. The frequent Left Bank Paris setting is atmospheric, but the tone is never as blithe as promised. I would also have liked some additional autobiographical material from Bakewell, who grew up in Reading, England (where I currently live) and met the existentialists through Sartre’s Nausea at age 16.

In the end the fault may not be her book’s but mine: I wasn’t up for fully engaging with a multi-subject biography packed with history and hard-to-grasp philosophical ideas. I’d recommend this to readers who long for bohemian Paris and have enjoyed either an existentialist work or a philosophical novel like Sophie’s World (Jostein Gaarder) or 36 Arguments for the Existence of God (Rebecca Goldstein).

My rating:

With thanks to Chatto & Windus for the review copy.

Further reading: If anything, I think I’m likely to try de Beauvoir’s autobiographical works – the descriptive language Bakewell quotes from them sounds appealing, and of course she was fundamental in paving the way for modern feminism.

You can read an excerpt from At the Existentialist Café, about de Beauvoir’s composition of The Second Sex, at Flavorwire. See also Bakewell’s Guardian list of 10 reasons why we should still be reading the existentialists.

Have you read anything by the existentialists? What would you recommend?

One for angsty, bookish types. In 2012 Anne Gisleson, a New Orleans-based creative writing teacher, her husband, sister and some friends formed an Existential Crisis Reading Group (which, for the record, I think would have been a better title). Each month they got together to discuss their lives and their set readings – both expected and off-beat selections, everything from Kafka and Tolstoy to Kingsley Amis and Clarice Lispector – over wine and snacks.

One for angsty, bookish types. In 2012 Anne Gisleson, a New Orleans-based creative writing teacher, her husband, sister and some friends formed an Existential Crisis Reading Group (which, for the record, I think would have been a better title). Each month they got together to discuss their lives and their set readings – both expected and off-beat selections, everything from Kafka and Tolstoy to Kingsley Amis and Clarice Lispector – over wine and snacks.

I enjoy Tom Perrotta’s novels: they’re funny, snappy, current and relatable; it’s no surprise they make great movies. I’ve somehow read seven of his nine books now, without even realizing it. Mrs. Fletcher is more of the same satire on suburban angst, but with an extra layer of raunchiness that struck me as unnecessary. It seemed something like a sexual box-ticking exercise. But for all the deliberately edgy content, this book isn’t really doing anything very groundbreaking; it’s the same old story of temptations and bad decisions, but with everything basically going back to a state of normality by the end. If you haven’t read any Perrotta before and are interested in giving his work a try, let me steer you towards Little Children instead. That’s his best book by far.

I enjoy Tom Perrotta’s novels: they’re funny, snappy, current and relatable; it’s no surprise they make great movies. I’ve somehow read seven of his nine books now, without even realizing it. Mrs. Fletcher is more of the same satire on suburban angst, but with an extra layer of raunchiness that struck me as unnecessary. It seemed something like a sexual box-ticking exercise. But for all the deliberately edgy content, this book isn’t really doing anything very groundbreaking; it’s the same old story of temptations and bad decisions, but with everything basically going back to a state of normality by the end. If you haven’t read any Perrotta before and are interested in giving his work a try, let me steer you towards Little Children instead. That’s his best book by far.

I read “We Love You Crispina” (13%), about the string of awful hovels a family of Chinese immigrants is forced to move between in early 1990s New York City. You’d think it would be unbearably sad reading about cockroaches and shared mattresses and her father’s mistress, but Zhang’s deadpan litanies are actually very funny: “After Woodside we moved to another floor, this time in my mom’s cousin’s friend’s sister’s apartment in Ocean Hill that would have been perfect except for the nights when rats ran over our faces while we were sleeping and even on the nights they didn’t, we were still being charged twice the cost of a shitty motel.” Perhaps I’m out of practice in reading short story collections, but after I finished this first story I felt absolutely no need to move on to the rest of the book.

I read “We Love You Crispina” (13%), about the string of awful hovels a family of Chinese immigrants is forced to move between in early 1990s New York City. You’d think it would be unbearably sad reading about cockroaches and shared mattresses and her father’s mistress, but Zhang’s deadpan litanies are actually very funny: “After Woodside we moved to another floor, this time in my mom’s cousin’s friend’s sister’s apartment in Ocean Hill that would have been perfect except for the nights when rats ran over our faces while we were sleeping and even on the nights they didn’t, we were still being charged twice the cost of a shitty motel.” Perhaps I’m out of practice in reading short story collections, but after I finished this first story I felt absolutely no need to move on to the rest of the book.

Impressive in scope and structure, but rather frustrating. If you’re hoping for another History of Love, you’re likely to come away disappointed: while that book touched the heart; this one is mostly cerebral. Metafiction, the Kabbalah, and some alternative history featuring Kafka are a few of the major elements, so think about whether those topics attract or repel you. Looking a bit deeper, this is a book about Jewish self-invention and reinvention. Now, when I read a novel with a dual narrative, especially when the two strands share a partial setting – here, the Tel Aviv Hilton – I fully expect them to meet up at some point. In Forest Dark that never happens. At least, I don’t think so.* I sometimes found “Nicole” (the author character) insufferably clever and inward-gazing. All told, there’s a lot to think about here: more questions than answers, really. Interesting, for sure, but not the return to form I’d hoped for.

Impressive in scope and structure, but rather frustrating. If you’re hoping for another History of Love, you’re likely to come away disappointed: while that book touched the heart; this one is mostly cerebral. Metafiction, the Kabbalah, and some alternative history featuring Kafka are a few of the major elements, so think about whether those topics attract or repel you. Looking a bit deeper, this is a book about Jewish self-invention and reinvention. Now, when I read a novel with a dual narrative, especially when the two strands share a partial setting – here, the Tel Aviv Hilton – I fully expect them to meet up at some point. In Forest Dark that never happens. At least, I don’t think so.* I sometimes found “Nicole” (the author character) insufferably clever and inward-gazing. All told, there’s a lot to think about here: more questions than answers, really. Interesting, for sure, but not the return to form I’d hoped for.