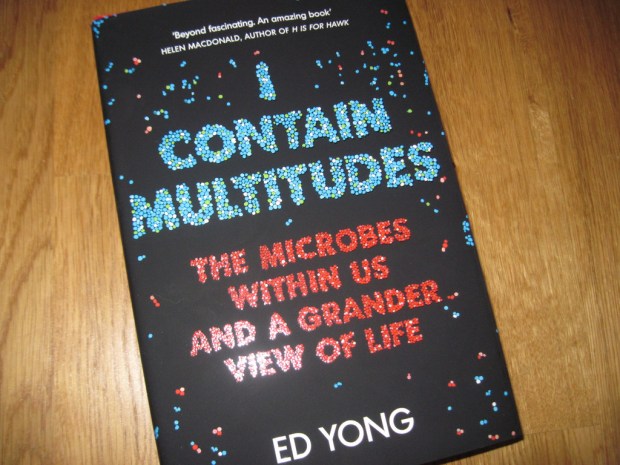

Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Ed Yong’s I Contain Multitudes

Ed Yong is a London-based science writer for The Atlantic and is part of National Geographic’s blogging network. I had trouble believing that I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes within Us and a Grander View of Life is his first book; it’s so fluent and engaging that it immediately draws you into the microbial world and keeps you marveling at its strange yet fascinating workings. Yong writes like a journalist rather than a scientist, and that’s a good thing: with an eye to the average reader, he uses a variety of examples and metaphors, intersperses personal anecdotes of visiting researchers at their labs or in the field, and is careful to recap important facts in a lucid way.

The book opens with a visit to San Diego Zoo (see the exclusive extract following my review), where we meet Baba the pangolin. But “Baba is not just a pangolin. He is also a teeming mass of microbes,” Yong explains. “Some of them live inside him, mostly in his gut. Others live on the surface of his face, belly, paws, claws, and scales.” Believe it or not, but we are roughly half and half human cells and microbial cells, making each of us – like all creatures – more of an ecosystem (another term is “holobiont”) than a single entity.

Microbes vary between species but also within species, so each individual’s microbiome in some ways reflects a unique mixture of genes and experiences. This is why people’s underarms smell subtly different, and how hyenas use their scent glands to convey messages. The microbiome may well be tailored to different creatures’ functions, so researchers at San Diego Zoo are testing swabs from their animals to see if there could be discernible signatures for burrowing or flying activities, or for disease. I was struck by the breadth of species considered here: not just mammals, but also invertebrates like beetles, cicadas, and squid – my entomologist husband would surely be proud. The “Us” in the subtitle is thus used very inclusively to speak of the way that microbes live in symbiosis with all living things.

I love the textured dust jacket too.

If I were to boil down Yong’s book to one message, it’s that microbes are not simply “bad” or “good” but have different roles depending on the context and the host. You can hardly dismiss all bacteria as germs that must be eradicated when there are thousands of benign species in your gut (versus fewer than 100 kinds that cause infectious diseases). If it weren’t for the microbes passed on to us at birth, we wouldn’t be able to digest the complex sugars in our mothers’ milk. Other creatures rely on bacteria to help them develop to adulthood, like the tube worms that thrive on Navy ship hulls at Pearl Harbor.

Yet Yong feels too little attention is given to beneficial microbes, and in many cases we continue the campaign to rid ourselves of them through overuse of antibiotics and taking cleanliness to unhelpful extremes. “We have been tilting at microbes for too long, and created a world that’s hostile to the ones we need,” he asserts.

The book is full of lines like that one that combine a nice turn of phrase and a clever literary allusion. In the title alone, after all, you have references to Walt Whitman (“I contain multitudes” is from his “Song of Myself”) and Charles Darwin (“there is grandeur in this view of life” is part of the closing sentence in his On the Origin of Species). Yong also sets up helpful analogies, comparing the immune system to a thermostat and antibiotics to “shock-and-awe weapons … like nuking a city to deal with a rat.”

History and future are also brought together very effectively, with the narrative looking backwards to Leeuwenhoek’s early microscope work and Pasteur and Koch’s germ theory, but also forwards to the prospects that current research into microbes might enable: eliminating elephantiasis, protecting frogs from deadly fungi via probiotics in the soil, fecal microbiota transplants to cure C. diff infections, and so on.

The possibilities seem endless, and this is a book that will keep you shaking your head in amazement. I’d liken Yong’s style to David Quammen’s or Rebecca Skloot’s. His clear and intriguing science writing succeeds in inspiring wonder at the natural world and at the bodies that carry us through it.

With thanks to Joe Pickering at The Bodley Head for the review copy.

My rating:

An exclusive extract from “PROLOGUE: A TRIP TO THE ZOO”

I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong

(The Bodley Head)

All of us have an abundant microscopic menagerie, collectively known as the microbiota or microbiome.1 They live on our surface, inside our bodies, and sometimes inside our very cells. The vast majority of them are bacteria, but there are also other tiny organisms including fungi (such as yeasts) and archaea, a mysterious group that we will meet again later. There are viruses too, in unfathomable numbers – a virome that infects all the other microbes and occasionally the host’s cells. We can’t see any of these minuscule specks. But if our own cells were to mysteriously disappear, they would perhaps be detectable as a ghostly microbial shimmer, outlining a now-vanished animal core.2

In some cases, the missing cells would barely be noticeable. Sponges are among the simplest of animals, with static bodies never more than a few cells thick, and they are also home to a thriving microbiome.3 Sometimes, if you look at a sponge under a microscope, you will barely be able to see the animal for the microbes that cover it. The even simpler placozoans are little more than oozing mats of cells; they look like amoebae but they are animals like us, and they also have microbial partners. Ants live in colonies that can number in their millions, but every single ant is a colony unto itself. A polar bear, trundling solo through the Arctic, with nothing but ice in all directions, is completely surrounded. Bar-headed geese carry microbes over the Himalayas, while elephant seals take them into the deepest oceans. When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon, they were also taking giant steps for microbe-kind.

When Orson Welles said ‘We’re born alone, we live alone, we die alone’, he was mistaken. Even when we are alone, we are never alone. We exist in symbiosis – a wonderful term that refers to different organisms living together. Some animals are colonised by microbes while they are still unfertilised eggs; others pick up their first partners at the moment of birth. We then proceed through our lives in their presence. When we eat, so do they. When we travel, they come along. When we die, they consume us. Every one of us is a zoo in our own right’– a colony enclosed within a single body. A multi-species collective. An entire world.

Footnotes

- In this book, I use the terms ‘microbiota’ and ‘microbiome’ interchangeably. Some scientists will argue that microbiota means the organisms themselves, while microbiome refers to their collective genes. But one of the very first uses of microbiome, back in 1988, used the term to talk about a group of microbes living in a given place. That definition persists today – it emphasises the ‘biome’ bit, which refers to a community, rather than the ‘ome’ best, which refers to the world of genomes.

- This imagery was first used by the ecologist Clair Folsome (Folsome, 1985).

- Sponges: Thacker and Freeman, 2012; placozoans: personal communication from Nicole Dubilier and Margaret McFall-Ngai.

My gut feeling: This book is a fine example of popular science writing, and has much to teach us about the everyday workings of our bodies. It’s one of my three favorites from the shortlist.

See also: Paul’s review at Nudge

Shortlist strategy: Tomorrow I’ll post a quick response to David France’s How to Survive a Plague, and on Sunday we will announce our shadow panel winner.

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

And if you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to one of the shortlist events being held this Saturday and Sunday.

Bibliotherapy for the New Year

In January lots of us tend to think about self-improvement for the New Year. Books can help! I’m resurrecting a post I first wrote as part of a series for Bookkaholic in April 2013 in hopes that those new to the concept of bibliotherapy will find it interesting.

I happen to believe – and I’m not the only one, not by a long shot – that a relationship with books can increase wellbeing. The right book at the right time can be a powerful thing, not just amusing and teaching, but also reassuring and even healing. Indeed, an ancient Greek library at Thebes bore an inscription on the lintel naming it a “Healing-Place for the Soul.”

The term “bibliotherapy,” from the Greek biblion (books) + therapeia (healing), was coined in 1916 by Samuel McChord Crothers (1857-1927). Crothers, a Unitarian minister and essayist, introduced the word in an Atlantic Monthly piece called “A Literary Clinic.” The use of books as a therapeutic tool then came to the forefront in America during the two world wars, when librarians received training in how to suggest helpful books to veterans recuperating in military hospitals. Massachusetts General Hospital had founded one of the first patients’ libraries, in 1844, and many other state institutions – particularly mental hospitals – had followed suit by the time of the First World War. Belief in the healing powers of reading was becoming more widespread; whereas once it had been assumed that only religious texts could edify, now it was clear that there could be benefits to secular reading too.

Read this for what ails you

Clinical bibliotherapy is still a popular strategy, often used in combination with other medical approaches to treat mental illness. Especially in the UK, where bibliotherapy is offered through official National Health Service (NHS) channels, library and health services work together to give readers access to books that may aid the healing process. Over half of England’s public library systems offer bibliotherapy programs, with a total of around 80 schemes documented as of 2006. NHS doctors will often write patients a ‘prescription’ for a recommended book to borrow at a local library. These books will usually fall under the umbrella of “self-help,” with a medical or mental health leaning: guides to overcoming depression, building self-confidence, dealing with stress, and so on.

Books can serve as one component of cognitive behavioral therapy, which aims to modify behavior through the identification of irrational thoughts and emotions. Bibliotherapy has also been shown to be an effective method of helping children and teenagers cope with problems: everything from parents’ divorce to the difficulties of growing up and resisting peer pressure. Overall, bibliotherapy is an appealing strategy for medical professionals to use with patients because it is low-cost and low-risk but disproportionately effective.

In addition to clinical bibliotherapy, libraries also support what is known as “creative bibliotherapy” – mining fiction and poetry for their healing powers. Library pamphlets and displays advertise their bibliotherapy services under names such as “Read Yourself Well” or “Reading and You,” with eclectic, unpredictable lists of those novels and poems that have proved to be inspiring or consoling. With all of these initiatives, the message is clear: books have the power to change lives by reminding ordinary, fragile people that they are not alone in their struggles.

The School of Life

London’s School of Life, founded by Alain de Botton, offers classes, psychotherapy sessions, secular ‘sermons,’ and a library of recommended reading tackle subjects such as job satisfaction, creativity, parenting, ethics, finances, and facing death with dignity. In addition, the School offers bibliotherapy sessions (one-on-one, for adults or children, or, alternatively, for couples) that can take place in person or online. A prospective reader fills out a reading history questionnaire before meeting the bibliotherapist, and can expect to walk away from the session with one instant book prescription. A full prescription of another 5-10 books arrives within a few days.

In 2011 The Guardian sent six of its writers on School of Life bibliotherapy sessions; their consensus seemed to be that, although the sessions produced some intriguing book recommendations, at £80 (or $123) each they were an unnecessarily expensive way of deciding what to read next – especially compared to asking a friend or skimming newspapers’ reviews of new books. Nonetheless, it is good to see bibliotherapy being taken seriously in a modern, non-medical context.

A consoling canon

You don’t need a doctor’s or bibliotherapist’s prescription to convince you that reading makes you feel better. It cheers you up, makes you take yourself less seriously, and gives you a peaceful space for thought. Even if there is no prospect of changing your situation, getting lost in a book at least allows you to temporarily forget your woes. In Comfort Found in Good Old Books (1911), a touching work he began writing just 10 days after his son’s sudden death, George Hamlin Fitch declared “it has been my constant aim to preach the doctrine of the importance of cultivating the habit of reading good books, as the chief resource in time of trouble and sickness.”

Indeed, as Rick Gekoski noted last year in an article entitled “Some of my worst friends are books,” literary types have always turned to reading to help them through grief. He cites the examples of Joan Didion coming to grips with her husband’s death in The Year of Magical Thinking, or John Sutherland facing up to his alcoholism in The Boy Who Loved Books. Gekoski admits to being “struck and surprised, both envious and a little chagrined, by how literary their frame of reference is. In the midst of the crisis…a major reflex is to turn, for consolation and understanding, to favorite and esteemed authors.” Literary critic Harold Bloom confirms that books can provide comfort; in The Western Canon he especially recommends William Wordsworth, Walt Whitman, and Emily Dickinson as “great poets one can read when one is exhausted or even distraught, because in the best sense they console.”

Just as in a lifetime of reading you will develop your own set of personal classics, you are also likely to build up a canon of favorite books to consult in a crisis – books that you turn to again and again for hope, reassurance, or just some good laughs. For instance, in More Book Lust Nancy Pearl swears by Bill Bryson’s good-natured 1995 travel book about England, Notes from a Small Island: “This is the single best book I know of to give someone who is depressed, or in the hospital.” (With one caveat: beware, your hospitalized reader may well suffer a rupture or burst stitches from laughing.)

Just what you needed

There’s something magical about that serendipitous moment when a reader comes across just the right book at just the right time. Charlie D’Ambrosio confides that he approaches books with a quiet wish: “I hope in my secret heart someone, somewhere, mysteriously influenced and moved, has written exactly what I need” (his essay “Stray Influences” is collected in The Most Wonderful Books). Yet this is not the same as superstitiously expecting to open a book and find personalized advice. Believe it or not, this has been an accepted practice at various points in history. “Bibliomancy” means consulting a book at random to find prophetic help – usually the Bible, as in the case of St. Augustine and St. Francis of Assisi. St. Francis’s first biographer, Thomas of Celano, wrote that “he humbly prayed that he might be shown, at his first opening the book, what would be most fitting for him to do” (in his First Life of St Francis of Assisi).

Perhaps meeting the right book is less like a logical formula and more like falling in love. You can’t really explain how it happened, but there’s no denying that it’s a perfect match. Nick Hornby likens this affair of the mind to a dietary prescription – echoing that medical tone bibliotherapy can often have: “sometimes your mind knows what it needs, just as your body knows when it’s time for some iron, or some protein” (in More Baths, Less Talking).

Entirely by happenstance, a book that recently meant a lot to me is one of the six inaugural School of Life titles, How to Stay Sane by psychotherapist Philippa Perry. Clearly and practically written, with helpful advice on how to develop wellbeing through self-observation, healthy relationships, optimism, and exercise, Perry’s book turned out to offer just what I needed.

I’ve been busy visiting family in the States but I’ll be back soon with a review of The Novel Cure from School of Life bibliotherapists Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin.