Tag Archives: West Virginia

R.I.P. Reads, Part I: Apostolides, Dahl, Harkness, Kingfisher & Kohda

Ghosts, witches, vampires, creepy underground things: It can only be Readers Imbibing Peril time of year! Here’s my first five reviews.

The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides (2025)

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of The Woman in Black, The Thirteenth Tale, and especially Wakenhyrst what with the local eel legends. The subplot about Ellen drifting apart from her best friend, a new mother, felt unnecessary, though I suppose was intended to bolster the main theme of women’s roles. There’s a twist that more seasoned readers of Gothic fiction and ghost stories might see coming. While I found this very readable and perfectly capably written, I didn’t get a sense of where the author hopes to fit in the literary market; she’s previously published a true crime narrative. Full disclosure: I once collaborated with Zoë on a Stylist assignment.

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of The Woman in Black, The Thirteenth Tale, and especially Wakenhyrst what with the local eel legends. The subplot about Ellen drifting apart from her best friend, a new mother, felt unnecessary, though I suppose was intended to bolster the main theme of women’s roles. There’s a twist that more seasoned readers of Gothic fiction and ghost stories might see coming. While I found this very readable and perfectly capably written, I didn’t get a sense of where the author hopes to fit in the literary market; she’s previously published a true crime narrative. Full disclosure: I once collaborated with Zoë on a Stylist assignment. ![]()

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the proof copy for review.

The Witches by Roald Dahl (1983)

I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book – about imagination and making the most of one’s time with grandparents. But in the back of my mind was Jen Campbell’s objection to the stereotypical equating of disfigurement with villainy. The Grand High Witch also speaks with a heavy German accent. It would be understandable to dismiss this as dated and clichéd, but I still found it worthwhile. It also fit into my project to read books from my birth year. (Free from a neighbour)

I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book – about imagination and making the most of one’s time with grandparents. But in the back of my mind was Jen Campbell’s objection to the stereotypical equating of disfigurement with villainy. The Grand High Witch also speaks with a heavy German accent. It would be understandable to dismiss this as dated and clichéd, but I still found it worthwhile. It also fit into my project to read books from my birth year. (Free from a neighbour) ![]()

The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness (2024)

Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to A Discovery of Witches. What I loved about that first novel was how the author drew on her knowledge of the history of science to create a believable backdrop for a story of witches, vampires and other supernatural beings that took place largely in Oxford and its medieval libraries. Each sequel has elaborated further adventures for Diana Bishop, a witch; her vampire husband, Matthew de Clermont; and their family members and other hangers-on. Their twins, especially Becca, have inherited some of Diana’s power. I read the first half of this last year and finally skimmed to the end last week, so I haven’t retained much. Diana is summoned to the ancestral seat of the Bishops in Massachusetts and finds herself part of a community of gossipy, catty witches. (Dahl was right, they’re everywhere!) She has some fun, folksy interactions but things soon get more serious as she girds herself for a showdown with the darker implications of her gift. Overall, this didn’t add much to the ongoing narrative and the love scenes veered too close to romantasy for my liking. (Public library)

Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to A Discovery of Witches. What I loved about that first novel was how the author drew on her knowledge of the history of science to create a believable backdrop for a story of witches, vampires and other supernatural beings that took place largely in Oxford and its medieval libraries. Each sequel has elaborated further adventures for Diana Bishop, a witch; her vampire husband, Matthew de Clermont; and their family members and other hangers-on. Their twins, especially Becca, have inherited some of Diana’s power. I read the first half of this last year and finally skimmed to the end last week, so I haven’t retained much. Diana is summoned to the ancestral seat of the Bishops in Massachusetts and finds herself part of a community of gossipy, catty witches. (Dahl was right, they’re everywhere!) She has some fun, folksy interactions but things soon get more serious as she girds herself for a showdown with the darker implications of her gift. Overall, this didn’t add much to the ongoing narrative and the love scenes veered too close to romantasy for my liking. (Public library) ![]()

What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher [Ursula Vernon] (2025)

The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after What Moves the Dead and What Feasts at Night. Alex Easton is a witty, gender-nonconforming narrator, which is why I persist with these novellas even though I’m underwhelmed by the plots. Denton, the American doctor friend from the first book, begs Easton to come to West Virginia: his cousin Oscar has gone missing in a mine after sending a series of alarming letters about a red light he saw in the depths. Easton and their right-hand man, Angus, soon encounter claustrophobia-inducing cave systems, various kinds of bad air and siphonophore-like marine creatures that can assemble to imitate other beings. (Why aren’t these on the cover, huh?!) In other intriguing matters, Denton seems to have something going on with his friend John Ingold, an Indigenous scientist. Though, as Easton frequently reminds themself, that’s none of our business. There are some great set-pieces and funny, if anachronistic, asides (on learning how to flick a lighter just right: “I used to practice it for hours as a teenager, in hopes of impressing girls. Look, girls were more easily impressed in those days. Shut up.”) But my feeling with all three books is that they’re over before they’ve barely begun, and they never deliver the expected horror. Smart-ass, queer fantasy/horror: these will be some people’s perfect books, just not mine. If you’re intrigued, do at least try the first one, which riffs on Poe. (Read via Edelweiss)

The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after What Moves the Dead and What Feasts at Night. Alex Easton is a witty, gender-nonconforming narrator, which is why I persist with these novellas even though I’m underwhelmed by the plots. Denton, the American doctor friend from the first book, begs Easton to come to West Virginia: his cousin Oscar has gone missing in a mine after sending a series of alarming letters about a red light he saw in the depths. Easton and their right-hand man, Angus, soon encounter claustrophobia-inducing cave systems, various kinds of bad air and siphonophore-like marine creatures that can assemble to imitate other beings. (Why aren’t these on the cover, huh?!) In other intriguing matters, Denton seems to have something going on with his friend John Ingold, an Indigenous scientist. Though, as Easton frequently reminds themself, that’s none of our business. There are some great set-pieces and funny, if anachronistic, asides (on learning how to flick a lighter just right: “I used to practice it for hours as a teenager, in hopes of impressing girls. Look, girls were more easily impressed in those days. Shut up.”) But my feeling with all three books is that they’re over before they’ve barely begun, and they never deliver the expected horror. Smart-ass, queer fantasy/horror: these will be some people’s perfect books, just not mine. If you’re intrigued, do at least try the first one, which riffs on Poe. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

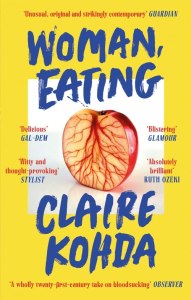

Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda (2022)

A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

More coming up on Halloween (thankfully, including books I liked better on average)!

The Truth According to Us and Safekeeping

They say there are only two basic plots: a stranger comes to town, or the hero sets off on a journey. So far this summer I’ve enjoyed two novels that exemplify one or the other model.

First is The Truth According to Us by Annie Barrows, co-author of the endearing The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. This atmospheric historical novel is set in the sweltering summer of 1938. Layla Beck, a spoiled senator’s daughter, has been sent to Macedonia, West Virginia by the WPA to document the town’s story in advance of its sesquicentennial. Her uncle pulls strings to get her the job even though he thinks his flighty niece is “exactly as fit to work on the project as a chicken is to drive a Buick.”

First is The Truth According to Us by Annie Barrows, co-author of the endearing The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. This atmospheric historical novel is set in the sweltering summer of 1938. Layla Beck, a spoiled senator’s daughter, has been sent to Macedonia, West Virginia by the WPA to document the town’s story in advance of its sesquicentennial. Her uncle pulls strings to get her the job even though he thinks his flighty niece is “exactly as fit to work on the project as a chicken is to drive a Buick.”

From a lunatic Civil War general onwards, Macedonia has certainly had a colorful history. The problem is that all the local lights want to skew history to present themselves in the most favorable light. This applies to the family Layla boards with as well, the Romeyns. Felix and Jottie’s father ran the American Everlasting Hosiery Company until a devastating fire some 20 years ago – blamed on Jottie’s old sweetheart, Vause Hamilton.

Now Felix’s twelve-year-old daughter Willa, who narrates much of the novel, wants to get to the bottom of things. What really happened during that factory fire? Why are the Romeyns snubbed around town? Has her divorcé father turned to bootlegging, and can she stop Miss Beck from bewitching him? Like Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird or Flavia de Luce in Alan Bradley’s mysteries, Willa is a spunky heroine whose curiosity carries the plot.

Once again Barrows makes good use of the epistolary format by inserting the letters Layla sends and receives during her time in Macedonia. Third person narration also gets us into the mind of Jottie, one of the strongest characters. However, later sections of the novel get a little bogged down in Jottie’s romantic history, and overall it is too long by at least a quarter. Barrows is better at capturing everyday speech and routines than momentous activities like a factory strike, but she certainly evokes the oppressive heat of a long American summer.

As Willa concludes, “The truth of other people is a ceaseless business. You try to fix your ideas about them, and you choke on the clot you’ve made.” This novel reminds us that others – whether strangers or family – are always a mystery, and history is a matter of interpretation.

Next up is Safekeeping, the debut novel from Jessamyn Hope. A bit like All the Light We Cannot See, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel from Anthony Doerr, the plot revolves around a priceless jewel. In this case it’s a medieval sapphire brooch that has been passed down through Adam’s family for centuries. In 1994, after the death of his grandfather, a Holocaust survivor, Adam undertakes a quest to return the brooch to the woman he fell in love with on an Israeli kibbutz and never forgot. Adam has his own problems – he’s a recovering junkie and alcoholic – but he feel he owes this to his grandfather’s memory.

Next up is Safekeeping, the debut novel from Jessamyn Hope. A bit like All the Light We Cannot See, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel from Anthony Doerr, the plot revolves around a priceless jewel. In this case it’s a medieval sapphire brooch that has been passed down through Adam’s family for centuries. In 1994, after the death of his grandfather, a Holocaust survivor, Adam undertakes a quest to return the brooch to the woman he fell in love with on an Israeli kibbutz and never forgot. Adam has his own problems – he’s a recovering junkie and alcoholic – but he feel he owes this to his grandfather’s memory.

A kibbutz undergoing the bitter transition from communalism to salaried work provides a vivid contrast to Adam’s native New York City. Hope populates her novel with a wonderful cast of eccentric characters. There’s Ulya, a Belarussian prima donna with a shoplifting habit; Claudette, a French Canadian Catholic crippled by mental health issues; Ziva, a kibbutz veteran who fights the changes tooth and nail despite advancing infirmity; and Ofir, a young man who endeavors to finish his military service early so he can return to his beloved piano.

I loved the way that Hope links the disparate characters in a constellation of connections. Acts of generosity, small or large, make a huge difference, even though betrayals past and present still linger. Close third person narration shifts easily between all the characters’ viewpoints, while two surprising historical interludes add depth. Hope handles flashbacks as elegantly as I’ve ever seen: you follow characters into their thoughts and suddenly snap back to the present right along with them.

I’ll confess I was slightly disappointed with the inconclusive ending. We follow the brooch rather than the characters, which means that in two cases we are left wondering about a person’s fate. Still, I was so impressed with the writing, especially the interweaving of past and present, that I will be eager to watch Hope’s career. Safekeeping is published by Fig Tree Books, a champion of modern Jewish literature, and has one of the most terrific book covers I’ve seen in a while.