Later than intended, I’m reporting back on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, which I started in late November, and a long-neglected 500+-page novel I plucked from my shelves. Both offered page-turning intrigue and a blend of history, magic, and pure weirdness. Many thanks to Laura for hosting Doorstoppers in December, which encouraged me to pick them up!

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood (2025)

I gave some initial thoughts about the book here to tie in with Margaret Atwood Reading Month. What I said then proved true of the book as a whole: it’s delightful though dense with detail and historical context. I did get a little bogged down in the names and details of decades worth of publishing, but there is some tasty gossip, such as the fact that Margaret Laurence spread mean rumours about her (and was a drunk) but later changed her ways. It’s been a lucky window of time for Atwood to live through: she has known simplicity and the need for do-it-yourself practicality, but has also experienced privilege, even luxury (multiple homes and worldwide travel). Mostly, she had the good fortune of being at the start of Canada’s literary boom. In the early 1960s, only five Canadian novels were published per year. Through her involvement with literary magazines and House of Anansi Press and her books on Susanna Moodie and the tropes of Canadian literature, she helped create the scene.

I gave some initial thoughts about the book here to tie in with Margaret Atwood Reading Month. What I said then proved true of the book as a whole: it’s delightful though dense with detail and historical context. I did get a little bogged down in the names and details of decades worth of publishing, but there is some tasty gossip, such as the fact that Margaret Laurence spread mean rumours about her (and was a drunk) but later changed her ways. It’s been a lucky window of time for Atwood to live through: she has known simplicity and the need for do-it-yourself practicality, but has also experienced privilege, even luxury (multiple homes and worldwide travel). Mostly, she had the good fortune of being at the start of Canada’s literary boom. In the early 1960s, only five Canadian novels were published per year. Through her involvement with literary magazines and House of Anansi Press and her books on Susanna Moodie and the tropes of Canadian literature, she helped create the scene.

There are frequent mentions of how people or events made their way into her fiction and poetry. Coyly, she writes, “I just have a teeming imagination. Also, like all novelists, I’m a kleptomaniac.” The page or two of context on each book is illuminating and it never becomes the tedious “I published this book … then I published this book” that she mentioned wanting to avoid in the introduction. Rather, these sections made me want to go reread lots of her books to appreciate them anew. I was also reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time, with topics and details that seem prophetic (she proposed Payback before the financial crisis hit, for instance). Some elements felt particularly timely: she experienced casual misogyny and an alarming number of near-misses – she says things like “I won’t give his name … you know who you are … though you’re probably dead” – and, through her involvement in bird conservation, she’s well aware of the disastrous environmental trajectory we’re on.

For a memoir, this is not especially forthcoming about the author’s inner life and emotions. Where it is, she masks the material in a layer of technique. So when she’s confessing to having an affair while married to Jim Polk (whom she met at Harvard), she writes it like a fairytale scene in which she went into the woods with a wolf. When she was fretting about Graeme Gibson’s reluctance to divorce her first wife and marry her, she imagines letters to her ‘inner advice columnist’. (Note: Gibson was her long-time partner and his sons were like her stepchildren but they never did marry – and he only ‘allowed’ her the one child, though she wanted two of her own. One ‘Jess Gibson’ has a speculative short story collection, The Good Eye, coming out in May 2026. No doubt her work will be compared with her mother’s, but bully for her for not using the name Atwood to try to ride her coattails.)

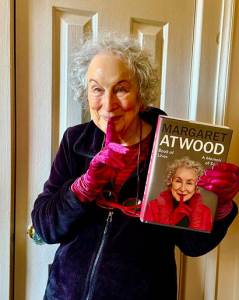

A cute pic from her Substack in November

One of the successful literary touches is the recurring “We Nearly Lose Graeme” segments about his risky behaviour and various mishaps. He had dementia and mini strokes before suffering a major one while in London with her for The Testaments tour; he died five days later. Her reflections on his death are poignant, but generic: “We can all believe three things simultaneously: The person is in the ground. The person is in the Afterlife. The person is in the next room. You keep expecting to see him. Even when you know it’s coming, a death is a shock.” At the crucial moment, she turns to the first-person plural and the second person.

I skimmed some of the bits about Graeme’s earlier life and the behind-the-scenes of publishing; I felt that he and many of her literary pals are more important to her than they are to readers. But that’s okay. The same goes for her earlier life; I noted that the account of her time as a summer camp counsellor felt more detailed than necessary. However, with her gift for storytelling, even the smallest incident can be rendered amusing. She looks for the humour, coincidence, or irony in any situation, and her summations and asides are full of dry humour. Some examples:

- “Spoiler: Jim and I eventually got married, one of the odder things to happen to both of us.”

- “After a while, the hand [at the window of her Harvard student accommodation] went away. It’s what you wish for in a disembodied hand.”

- “Eventually the iguana [inherited from her roommate] was given a new home at a zoo among other iguanas, where it was probably happier. Hard to tell.”

It’s not a book for the casual reader who kinda liked one or two Atwood novels; it’s more for the diehard fans among us, and offers a veritable trove of stories and photographs. But don’t expect a tell-all. Think of this more as a companion to her oeuvre. The title feels literal in that it’s as if she’s lived several lives: the wilderness kid, the literary ingénue, the family and career woman, the philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all of her incarnations into one, instead leaving all of the threads trailing into the beyond. If anything, “Peggy Nature” (her name from summer camp) is the role that has persisted. I probably liked the childhood material most, which makes sense as it’s what she’s looking back on with most fondness. Towards the close, Atwood mentions her heart condition and seems perfectly accepting of the fact that she won’t be around for much longer. But her body of work will endure. I’m so grateful for it and for the gift of this self-disclosure, however coy. (Can I be greedy and hope for another novel?) She leaves this message: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.” [570 pages] (Public library) ![]()

The End of Mr. Y by Scarlett Thomas (2006)

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

The plot is pretty bonkers and I’m not sure I can satisfactorily explain its internal logic now, but as is true of the best doorstoppers, it absorbed me completely. I read it very quickly (for me) and even read 120 pages in one sitting thanks to my cat pinning me to the sofa. It also felt prescient in discussing “machine consciousness” – a topic adjacent to artificial intelligence. Ariel is a Disaster Woman avant la lettre, living on noodles and cut-price wine. Her current ‘relationship’ consisting of rough sex with a married professor is the latest in a string of unhealthy connections. But time travel offers the possibility not just of reversing her own mistakes, but of going right back to the start of humanity. Verging on steampunk, this was much better than the other Thomas novels I’ve read, The Seed Collectors and Oligarchy. It was longlisted for the Orange (Women’s) Prize and would be a great choice for readers of Nicola Barker and Susanna Clarke. [502 pages] (Secondhand – Book-Cycle, Exeter; it’s been on my shelves since 2016!) ![]()

Does the Atwood bio say anything about A. S. Byatt?

LikeLike

Alas, I’ve had to return it to the library so I can’t check the index for you. Anyone else who owns a copy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, sorry, I got her mixed up with Margaret Drabble. It serves me right for not looking it up before I asked.

LikeLike

No worries! It is entirely possible that there is a passing comment to A.S. Byatt in this too.

LikeLike

[…] Rebecca @ Bookish Beck: Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas […]

LikeLike

Scarlett Thomas is one of those writers I see around a lot but am never sure whether or not to try. I’m glad you liked this one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Her early works earned comparisons with Douglas Coupland. I think by this one she’d found her stride. I enjoyed it a lot!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hoever good they are , you have to be In The Mood for doorstoppers. And I’m just – not – at the moment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very true. Luckily these two went down a treat. I did start a few others that I didn’t have staying power with, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hats off on two doorstoppers! And good on your cat for pinning you down 🙂 sometimes it is better when you have an excuse for not getting up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He is rarely a lap cat so it was a lucky treat. (Because I had the comfy blankie on me.)

LikeLike

It doesn’t surprise me that Atwood keeps her emotions behind a veil of devices. That seems in keeping with her writing. I will eventually pick this one up and probably skim it as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s well worth it for a fan, but I think it would also be possible to read it parts at a time, or just pick out the bits that apply to a certain novel you want to reread.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood: For diehard fans, this companion to her oeuvre is a trove of stories and photographs. The context on each book is illuminating and made me want to reread lots of her work. I was reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time. The title feels literal in that Atwood has been wilderness kid, literary ingénue, family and career woman, philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all her incarnations into one, instead leaving the threads trailing into the beyond. […]

LikeLike

I appreciated the fact that MA makes it clear that ML was very nice and kind when she wasn’t drinking but, during the course of a day, would sink into a sort of “darkness” as she called it. so that we understand clearly that it was the alcoholism, not a personality issue. And I thought it was shocking that ML’s daughter would so casually say that her mother was a “drunk” and there was nothing anyone could do about it, but THEN spread around like gossip (including to another writer, Adele Wiseman) the fact that anyone called to enquire. But there you have it, just a few lines in a 600+ page memoir and there’s something to say about it. Like you, I found the amount of material almost overwhelming, and I already plan to reread. Like you, I also enjoyed the early parts more; I felt it was written more novelistically. I”m not sure I would have wanted a tell-all, but I agree that it never feels like that and anyone looking for it would be very disappointed. When that Scarlett Thomas was nominated for the (then) Orange Prize, I was shocked to find myself racing through it. It had seemed the one that would take the longest to read, but it was definitely not! (No Byatt or Drabble in the index of TBofL, BTW.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Soooo many stories. So much to take in. I’m sure you have your own copy to refer back to?

LikeLike

I splurged and used MARM as justification, when I found out it was going to be published in November. The library hold lists on her books up here stretch for years, literally.

LikeLike

[…] favourite books as a child. Especially early on, I found this as thrilling as The Absolute Book and The End of Mr. Y. Whereas those doorstoppers held my interest all the way through, though, this became a trudge at a […]

LikeLike