Grief in Literature: Michel Faber and Cathy Rentzenbrink

On Tuesday night I had the chance to see Michel Faber in conversation with Cathy Rentzenbrink at Foyles bookstore in London. The topic was grief in literature, and specifically Faber’s book of poems in honor of his late wife, Undying: A Love Story (which I reviewed here in July). Faber had always written occasional poems, he said, “sort of kind of clever” stuff that he would have taken little note of if he encountered it from another author; the only really good ones, he thought, were about illness, based on his time as a nurse. So when there came this huge uprising of poems about Eva’s last illness, he felt they were a more appropriate way of commemorating her life than a novelistic narrative.

A six-floor bookshop: heaven for book lovers.

Rentzenbrink mentioned two things that particularly struck her: how Eva emerges in the fullness of her personality in the course of these poems, and the fact that the book is not angry. Faber explained that Eva herself was not angry. She did not think of multiple myeloma as her enemy and had no illusions about ‘beating’ cancer; instead, she just tried to achieve the best quality of life and the longest lifespan possible. In fact, she found cancer interesting, Faber recalled: she researched it as much as she could and followed its course with a certain curiosity. He contrasted her experience with that of an acquaintance in the Scottish Highlands who had the same disease and wanted to know nothing about it, leaving it all in the hands of her doctors. Faber believes this ignorance shortened their friend’s life unnecessarily.

Making sure that Eva came through as a real person in the poems was a struggle, Faber confessed. To start with his editors at Canongate, many of whom knew Eva, were frustrated that Undying was mercilessly medical, describing the process and aftermath of cancer treatment. A few poems, then, he wrote as a direct response to that criticism, almost as if ‘on commission’, he said, to infuse the book with more of Eva’s personality.

Only two of the poems were written while Eva was still alive, Faber noted. One was “Nipples,” written at her bedside just 10 days before her death. Eva had dealt with the pain and indignity of her illness admirably, but plasmacytomas – big purple welts all over her skin – truly broke her spirit, he revealed. His poem is a strangely erotic take on these blemishes: “Excited peaks of plasma. … Your flesh is riotous with the pleasure / of predatory cells.”

Cathy Rentzenbrink and Michel Faber

There’s irony there, and a certain dark humor in many of the rest. “There are so many absurdities when a body is breaking down spectacularly,” Faber said. And yet the last two years of Eva’s life were “incredibly intimate and tender,” as a fiercely independent woman ended up very frail and completely dependent on him as her carer. Likewise, Faber had to shift from creativity to practicality to cope with household tasks plus caregiving.

Cathy Rentzenbrink was the perfect person to interview Faber. She is the author of a bereavement memoir, The Last Act of Love, about her brother’s death after eight years in a vegetative state. Moreover, her mother survived a bout with cancer at the same age as Eva; she was heavily involved with that process through accompanying her to chemotherapy appointments. I was a bit disappointed that Rentzenbrink didn’t get to speak more about her own grief and the experience of crafting a narrative out of it. Faber said he too had envisioned more of a dialogue, but that Rentzenbrink thought it would be inappropriate for her to talk about herself and generously kept the focus on his work instead.

I also would have appreciated more context about grief literature in general, and poetry in particular. Faber did mention that there are many kinds of grief poetry. For instance, Thomas Hardy was still writing poems about his first wife decades after her death. Faber consciously avoided writing elegant, well-formed poetry like some that he’s read; instead he wanted his poems to be raw, direct, even shocking. Contrast that with the rainbows and heavenly visions of much of what’s out there. This came home to me a few weeks ago at my husband’s uncle’s funeral. Three poems were recited in the course of the ceremony, all of them heavily clichéd and unfailingly rhymed. This meant that the speakers ended up using singsong voices. In Faber’s poems, though, end rhymes are rare. I noticed them more, along with the sibilance and internal rhymes, through the emphasis he lent when reading aloud.

Rentzenbrink insisted there is still life to be lived for the grieving. As if to reinforce her point, Faber openly admitted to his relationship with a fellow writer who also lost a longtime partner, Louisa Young, whom he met the year after Eva’s death. He’s aware that this poses a marketing problem: he’s no longer the disconsolate soul in rumpled clothing, barely surviving without his spouse. (Indeed, he looked well put together and hip in his blue leather jacket and bright orange shoes, and his blond mop makes him appear much younger than he is.) Thinking also of a widower friend, Rentzenbrink said that her feeling was “he looked after her for so many years; he can have a little fun now!”

Rentzenbrink insisted there is still life to be lived for the grieving. As if to reinforce her point, Faber openly admitted to his relationship with a fellow writer who also lost a longtime partner, Louisa Young, whom he met the year after Eva’s death. He’s aware that this poses a marketing problem: he’s no longer the disconsolate soul in rumpled clothing, barely surviving without his spouse. (Indeed, he looked well put together and hip in his blue leather jacket and bright orange shoes, and his blond mop makes him appear much younger than he is.) Thinking also of a widower friend, Rentzenbrink said that her feeling was “he looked after her for so many years; he can have a little fun now!”

As to Faber’s professional future, he reiterated that he does not plan to write any more novels for adults. All of his fiction is about characters desperate to transcend, he said, and now it’s time for him to do that in his own life. He’s pondered a couple of nonfiction projects about aesthetics and music, but for now his next goal is a YA adventure novel. Whenever plaintive readers beg him for future novels, he cheekily asks whether they’ve read his whole back catalogue – including two collections of short stories, always a hard sell for novel readers. I have six more of Faber’s books to get to myself, so that’s plenty to fuel me in the years ahead. I came away from this event with a greater appreciation for the poems in Undying and a deep respect for a man aware of the seasons of his life, writing and caregiving among them.

Happy 200th Birthday, Charlotte Brontë!

Today marks a big anniversary: the bicentennial of Charlotte Brontë’s birth. I’ve noticed a whole cluster of books being published or reissued in time for her 200th birthday, many of which I’ve reviewed with enjoyment; some of which I’ve sampled and left unfinished. I hope you’ll find at least one book on this list that will take your fancy. There could be no better time for going back to Charlotte Brontë’s timeless stories and her quiet but full life story.

Short Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre

MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD.

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, edited by Tracy Chevalier

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, edited by Tracy Chevalier

A mixed bag. Although there are some very good stand-alone stories (from Tessa Hadley, Sarah Hall, Emma Donoghue and Elizabeth McCracken, as you might expect), ultimately the theme is not strong enough to tie them all together and some seem like pieces the authors had lying around and couldn’t figure out what else to do with. Think about it this way: what story isn’t about romance and the decision to marry?

A few of the tales do put an interesting slant on this age-old storyline by positing a lesbian relationship for the protagonist or offering the possibility of same-sex marriage. Then there are the stories that engage directly with the plot and characters of Jane Eyre, giving Grace Poole’s (Helen Dunmore) or Mr. Rochester’s (Salley Vickers) side of things, putting Jane and Rochester in couples therapy (Francine Prose), or making Jane and Helen Burns part of a post-WWII Orphan Exchange (Audrey Niffenegger). My feeling with these spinoff stories was, I’m afraid, what’s the point? Plus there were a number of others that just felt tedious.

My least favorites were probably by Lionel Shriver (incredibly boring!), Kirsty Gunn (unrealistic, and she gives the name Mr. Rochester to a dog!) and Susan Hill (the title story, but she’s made it about Wallis Simpson – and has the audacity to admit, as if proudly, that she’s never read Jane Eyre!). On the other hand, one particular standout is by Elif Shafak. A Turkish Muslim falls in love with a visiting Dutch student but is so unfamiliar with romantic cues that she doesn’t realize he isn’t equally taken with her.

In Patricia Park’s story, my favorite of all, a Korean girl from Buenos Aires moves to New York City to study English. Park turns Jane Eyre on its head by having Teresa give up on the chance of romance to gain stability by marrying Juan, the St. John Rivers character. I loved getting a glimpse into a world I was entirely ignorant of – who knew there was major Korean settlement in Argentina? This also redoubled my wish to read Park’s novel, Re Jane. She’s working on a second novel set in Buenos Aires, so perhaps it will expand on this story.

The Bookbag reviews

Charlotte Brontë’s Secret Love by Jolien Janzing

by Jolien Janzing

Charlotte and Emily Brontë’s time in Belgium – specifically, Charlotte’s passion for her teacher, Constantin Heger – is the basis for this historical novel. The authoritative yet inviting narration is a highlight, but some readers may be uncomfortable with the erotic portrayal; it doesn’t seem to fit the historical record, which suggests an unrequited love affair.

Sanctuary by Robert Edric

by Robert Edric

Branwell Brontë narrates his final year of life, when alcoholism, mental illness and a sense of disgrace hounded him to despair. I felt I never came to understand Branwell’s inner life, beneath the decadence and all the feeling sorry for himself. This gives a sideways look at Charlotte, Emily and Anne, though the sisters are little more than critical voices here; none of them has a distinctive personality.

Mutable Passions : Charlotte Brontë: A Disquieting Affair by Philip Dent

: Charlotte Brontë: A Disquieting Affair by Philip Dent

Dent focuses on a short period in Charlotte Brontë’s life: with all her siblings dead and Villette near completion, a surprise romance with her father’s curate lends a brief taste of happiness. Given her repeated, vociferous denial of feelings for Mr. Nicholls, I had trouble believing that, just 20 pages later, his marriage proposal would provoke rapturous happiness. To put this into perspective, I felt Dent should have referenced the three other marriage proposals Brontë is known to have received. Overwritten and suited to readers of romance novels than to Brontë enthusiasts, this might work well as a play. Dent is better at writing individual scenes and dialogue than at providing context.

Two Abandonees

I had bad luck with these two novels, which both sounded incredibly promising but I eventually abandoned (along with Yuki Chan in Brontë Country, featured in last month’s Six Books I Abandoned Recently post):

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

Jane Steele is not quite Jane Eyre, though her life seems to mirror that of Brontë’s heroine in most particulars. How she differs is in her violent response to would-be sexual abusers. She’s a feminist vigilante wreaking vengeance on her enemies, whether her repulsive cousin or the vindictive master of “Lowan Bridge” (= Cowan Bridge, Brontë’s real-life school + Lowood, Jane Eyre’s). I stopped reading because I didn’t honestly think Faye was doing enough to set her book apart. “Reader, I murdered him” – nice spin-off line, but there wasn’t enough original material here to hold my attention. (Read the first 22%.)

The Madwoman Upstairs by Catherine Lowell

The Madwoman Upstairs by Catherine Lowell

There was every reason for me to love this novel – awkward American narrator, Oxford setting, Brontë connections aplenty, snarky literary criticism – but I got bored with it. Perhaps it was the first-person narration: being stuck in sarcastic Samantha Whipple’s head means none of the other characters feel real; they’re just paper dolls, with Orville a poor excuse for a Mr. Rochester substitute. I did laugh out loud a few times at Samantha’s unorthodox responses to classic literature (“Agnes Grey is, without question, the most boring book ever written”), but I gave up when I finally accepted that I had no interest in how the central mystery/treasure hunt played out. (Read the first 56%.)

An Excellent Biography

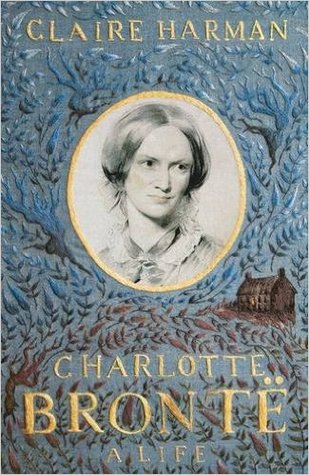

If I could recommend just one book from the recent flurry of Brontëana, it would be Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman, which I reviewed for For Books’ Sake back in November.

If I could recommend just one book from the recent flurry of Brontëana, it would be Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman, which I reviewed for For Books’ Sake back in November.

One of the things Harman’s wonderful biography does best is to trace how the Brontës’ childhood experiences found later expression in their fiction. A chapter on the publication of Jane Eyre (1847) is a highlight. Diehard fans might not encounter lots of new material, but Harman does make a revelation concerning Charlotte’s cause of death – not TB, as previously believed, but hyperemesis gravidarum, or extreme morning sickness. This will help you appreciate afresh the work of a “poet of suffering” whose novels were “all the more subversive because of [their] surface conventionality.” Interesting piece of trivia for you: this and the Janzing novel (above) open with the same scene from Charlotte’s time in Belgium.

Have you read any of these, or other recent Brontë-themed books? What were your thoughts?

Alive, Alive Oh!: Diana Athill in Person

Last night I was lucky enough to see 98-year-old literary legend Diana Athill in conversation with Erica Wagner at Foyles bookstore in London. Athill, born in 1917, has been an inspiration to me ever since I discovered her work five or so years ago. She didn’t publish anything until she was in her forties, and didn’t reach true acclaim until her eighties, when she released an incredible series of memoirs. Hers is an encouraging story of late-life success and what can be achieved with diligence and good fortune.

What strikes you immediately about Athill is her elegance. Although her hair is thinning and she speaks with a slight slur out of the left side of her mouth, she retains her eagle eye and hawkish profile. That cut-glass BBC pronunciation is not just “the Queen’s English” but a voice just like the Queen’s – she even occasionally used “One” to speak about her own experience. Her look, too, was perfectly put together: a beautiful, multicolored Nehru jacket over a blue silk blouse, accessorized with chunky blue and silver jewelry. Though she was brought in by wheelchair and needed a lot of help getting on the podium – she apologized for her belabored entry – she hardly seems on the brink of death.

Diana Athill and Erica Wagner.

Erica Wagner, too, is one of my heroes: an American expat who served as literary editor of the London Times from 1996 to 2013 and is now a contributing writer with New Statesman and a Harper’s Bazaar consulting literary editor. She drew Athill out on many of the topics from her latest memoir, Alive, Alive Oh! And Other Things that Matter, including the unexpected pregnancy and miscarriage she experienced in her forties, memories of visiting Tobago, and the downsizing that preceded her move into a retirement home.

Athill recalled the absolute joy she felt upon waking up from her miscarriage, a medical emergency that could well have ended in her death. It was a feeling that started in her stomach and rose up through her body – “I’m alive!” she remembered exulting. Losing her chance at motherhood was not a haunting sadness for her, she remarked; to her surprise, she got over it easily. Part of it was that she had never felt maternal yearning; she vividly pictures being 19, looking at someone’s baby lying on a bed and wondering to herself how she should feel about this creature. Ultimately, she decided, “I’d much rather pick up a puppy!”

Athill recalled the absolute joy she felt upon waking up from her miscarriage, a medical emergency that could well have ended in her death. It was a feeling that started in her stomach and rose up through her body – “I’m alive!” she remembered exulting. Losing her chance at motherhood was not a haunting sadness for her, she remarked; to her surprise, she got over it easily. Part of it was that she had never felt maternal yearning; she vividly pictures being 19, looking at someone’s baby lying on a bed and wondering to herself how she should feel about this creature. Ultimately, she decided, “I’d much rather pick up a puppy!”

That sort of forthrightness was evident in a number of pithy responses Athill gave to audience members’ questions. Asked “is it better to have loved and lost than never to have loved?” she replied with a simple, emphatic “YES!” Does she have anything planned for her 100th birthday? “I choose not to think about it,” she quipped. Has age mellowed her? “A bit,” she hedged, before adding that she is now more tolerant and minds less what others think of her.

One of her key pieces of advice is to avoid romanticism and possessiveness. That certainly played out in her unconventional personal life: she never married but was with her partner, a black man, for some four decades, and after he divorced his wife they formed an unusual household arrangement with his new lover and her family.

If Athill was never possessive in love affairs, however, she did struggle with it in terms of belongings. It was agonizing, she noted, to give up most of her things – especially her books – when moving into a tiny room in a Highgate retirement home. Now, though, she doesn’t mind at all. “When you get very old you really don’t need much,” she insisted. Early on she adopted Montaigne’s practice of thinking about death once a day to get used to the idea. None of the 40 residents at her home minds the thought of being dead; what they don’t like is the idea of dying. Each one hopes to bypass the horrid death and have the easy one instead.

Writing started as a therapeutic exercise for Athill. She wrote Instead of a Letter, about a painful love affair from her youth, because she had a deep sense of failure as a woman. After writing about it, though, she felt completely better, like a new person. Several of her other nonfiction books had a similar motivation: they were a way of getting rid of sad experiences, her own or others’ that she was close to.

When encouraged to write about her long career as a literary editor, she initially thought she couldn’t do it; she only wrote to “cure nasty things” by getting to the bottom of them as honestly as possible. However, she managed to convince herself she could also write for fun, and Stet, about her work with André Deutsch, was the delightful result. Asked for some of her favorite authors, she named Molly Keane (as a person as well as a writer), Jean Rhys, and Philip Roth (not as a person, she hastened to add!). Rhys and V.S. Naipaul, two of her illustrious clients, never needed a word editing, she recalled; however, they did occasionally need a nanny.

When encouraged to write about her long career as a literary editor, she initially thought she couldn’t do it; she only wrote to “cure nasty things” by getting to the bottom of them as honestly as possible. However, she managed to convince herself she could also write for fun, and Stet, about her work with André Deutsch, was the delightful result. Asked for some of her favorite authors, she named Molly Keane (as a person as well as a writer), Jean Rhys, and Philip Roth (not as a person, she hastened to add!). Rhys and V.S. Naipaul, two of her illustrious clients, never needed a word editing, she recalled; however, they did occasionally need a nanny.

Having seen publishing from the other side now, as an author, Athill believes that being read with absolute attention by an editor – as opposed to getting halfway through a review and finding one’s work hasn’t been understood at all – is heaven. So although she was initially surprised that she would be given an editor, she joked, in the end she was grateful. Publishing is now much more of a business, she acknowledges, but she still feels that many people are in it for the right reason: simply because they love books.

In the wider world, so much has changed for the worse over the past near-century she’s been alive, but medicine and education are two things that have gotten better. “Long live the National Health!” she cried. (Hear, hear!) On the other hand, it was particularly interesting to hear Athill sigh that she hasn’t been a very good feminist; although she supports the idea, she feels she should have been more engaged. For example, she knew very well that she earned less than a man in her position would have at André Deutsch, but never made anything of it.

In the wider world, so much has changed for the worse over the past near-century she’s been alive, but medicine and education are two things that have gotten better. “Long live the National Health!” she cried. (Hear, hear!) On the other hand, it was particularly interesting to hear Athill sigh that she hasn’t been a very good feminist; although she supports the idea, she feels she should have been more engaged. For example, she knew very well that she earned less than a man in her position would have at André Deutsch, but never made anything of it.

In the end, Athill thinks of luck as what’s given to you rather than something you make. “On the whole, I have been so lucky in my life,” she marveled towards the close of last night’s wonderful event. “I can’t really complain about anything.”

I’ve now read all Athill’s work, even her rather obscure novel and short story collection. Her latest book doesn’t live up to her few best memoirs, but it’s an essential read for a devoted fan. For readers new to her work, I’d recommend starting with Somewhere Towards the End, followed by Stet. From there you might try her book of correspondence with American poet Edward Field, Instead of a Book, or her memoir of childhood, Yesterday Morning.

I’ve now read all Athill’s work, even her rather obscure novel and short story collection. Her latest book doesn’t live up to her few best memoirs, but it’s an essential read for a devoted fan. For readers new to her work, I’d recommend starting with Somewhere Towards the End, followed by Stet. From there you might try her book of correspondence with American poet Edward Field, Instead of a Book, or her memoir of childhood, Yesterday Morning.

Psssssst! I have the dirt on a forthcoming Athill publication – and here I thought Alive, Alive Oh! would be her last book for sure. It will be the diary of a trip she took to Florence in 1948. Italy seemed to have bounced back from six years of wartime much more quickly than England, so after that sense of imprisonment it was a chance to enjoy life once again. I’ll be keen to read this rare ‘found document’.

A Book-Themed Concert and Goody Bag

On Saturday my husband and I headed to Hungerford to see The Bookshop Band for the second time. A year and a half ago I first had the chance to see them live at the 2014 Hungerford Literary Festival, when they gave a performance tied in with Rachel Joyce’s release of The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy.

The band formed about five years ago to provide music for author events at their local bookshop, Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, England. Since then they’ve written somewhere between 120 and 150 songs inspired by books. Their basic genre is indie folk, with plenty of guitar, ukulele and cello as well as a bunch of improvised percussion and three intermingled voices. Depending on the book in question, though, the feel can vary widely, ranging from sweet to bizarre or haunting. Especially when I’ve read the book being sung about, it’s intriguing to see what the musicians have picked up on – often something very different from what I would as a reader and reviewer.

This year the band (now down to two members) is making an effort to record and release all their songs in 10 albums. I participated in a crowdfunding project so am lucky enough to receive all their new releases in digital format before they’re available as printed CDs. The first album is Curious and Curiouser, the title track of which was inspired by Alice in Wonderland. Other sets of songs are based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the steampunk novel The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder, while “Once Upon a Time,” a commission for radio, strings together famous first lines from fiction.

This year the band (now down to two members) is making an effort to record and release all their songs in 10 albums. I participated in a crowdfunding project so am lucky enough to receive all their new releases in digital format before they’re available as printed CDs. The first album is Curious and Curiouser, the title track of which was inspired by Alice in Wonderland. Other sets of songs are based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the steampunk novel The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder, while “Once Upon a Time,” a commission for radio, strings together famous first lines from fiction.

My favorite Bookshop Band song (so far) is “Bobo and the Cattle,” inspired by Alexandra Fuller’s Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight. Two great ones new to me from Saturday’s performance were “Faith in Weather,” based on Central European fairy tales, and “You Make the Best Plans, Thomas,” about Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies.

You can listen to lots of their songs on their Bandcamp page and dozens of videos of their performances are on YouTube and Vimeo (I’ve linked to several above). When performing events they often get the authors to play with them: Louis de Bernières pitched in with mandolin on a song about The Dust that Falls from Dreams, and Yann Martel played glockenspiel while promoting The High Mountains of Portugal.

We had started off the day with lunch at a Berkshire country pub, The Pot Kiln, where we didn’t mind the 40-minute wait for food because we had books and half-pints of beer and cider to while away the time over as sunshine poured through the windows. The menu is mostly based around game shot by the chef himself in the fields opposite the pub, so we indulged in a venison and wild boar hot dog and venison Scotch eggs before setting off on a windy several-mile walk near Combe Gibbet and then continuing on to Hungerford.

Now for the goody bag: on the venue tables the owner of Hungerford Bookshop had placed a ten-question literary quiz to work on and hand in during the intermission. I was fairly confident on some of my answers, had a guess at the others, and after literally about 45 minutes of wrestling with anagrams finally figured out that “Lobbing Slates” gives the name of novelist Stella Gibbons. We won with 7 out of 10 correct; an elderly lady joked that we’d Googled all the answers, but I pointed out that we don’t own a smartphone between us! Now, I suspect we were actually the only entry, but that doesn’t diminish our accomplishment, right?! I was delighted to win a couple of free books I hadn’t necessarily intended on reading but now certainly will, plus a metal bookmark and a notebook, all in a limited-edition “Books Are My Bag” tote designed by Tracey Emin.

All in all, a fantastic and mostly bookish day out!

If you live in the UK and get the chance, don’t hesitate to go see The Bookshop Band play; they’re touring widely this year.

Dickens: Not Just for Christmas

Charles Dickens is almost singlehandedly responsible for creating our view of the traditional Christmas. It’s no surprise, then, that many people associate him with the holiday season. An armchair next to a fire somehow seems like the ideal place for curling up with one of his chunky tomes. I know some readers who try to pick up one of his books every winter, like Lucy over at Literary Relish. This year my husband is reading a facsimile edition of the original serialized version of Hard Times (re-issued by Stanford University’s Discovering Dickens project in 2005) in the run-up to Christmas, and also plans to get through The Cricket on the Hearth. One of my goals for 2016 is to return to Dombey and Son, which I got about 200 pages into a few years ago but never managed to finish.

We’ve also been lucky enough to catch a number of Dickens-themed theatre productions over the years: in London, Patrick Stewart’s one-man production of A Christmas Carol and Simon Callow’s one-man The Mystery of Charles Dickens, an open-air version of A Christmas Carol that took place around the streets of York, and, this year, Dickens Abridged at Norden Farm Centre for the Arts near Maidenhead. This was from Adam Long, the same brilliant mind that, as a founding member of The Reduced Shakespeare Company, helped create The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged) as well as The Complete History of America (abridged) and The Bible: The Complete Word of God (abridged). I’ve seen four of their shows now, and all were utterly hilarious.

A spooky scene: walking the streets of York for a wandering production of A Christmas Carol.

York Christmas Carol: stopping for a scene in a graveyard.

To our surprise, Dickens Abridged was basically a musical in a comedy folk style. We were reminded of Flight of the Conchords or Folk On. There were just four male actors on stage playing all the historical and fictional roles, including, of course, all the female ones. Some of Dickens’s novels didn’t even get a mention (though did I really expect Barnaby Rudge to turn up?!), others got the briefest of nods, and some came in for extensive treatment.

There were long scenes from Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities, and A Christmas Carol, whereas some of the more obscure works merited just few-line limericks sung to a simple guitar accompaniment. The problem with these was that the actor was singing so quickly and without amplification that, if you didn’t already know the novel’s storyline, his extremely abridged version would leave you none the wiser.Among the show’s highlights were the guillotine scene in A Tale of Two Cities, Tiny Tim’s amazing transforming crutch, and the refrain sung by Dickens: “I am a man of anxiety and sorrow” – sung in a 1980s power ballad style, if you can imagine that.

What I found most remarkable about this production was how it was not just the abridged works of Dickens but also the abridged life of Dickens. His time at the blacking factory and his marriage to Catherine Hogarth are two turning points that the play emphasized to good effect. Some readers only vaguely familiar with Dickens might not know about his troubled marriage and the divorce case that left Catherine in disgrace as Dickens took up with a mistress, young actress Nelly Ternan. So while Dickens Abridged was heavy on the laughs, it was also informative and thoughtful.

Dickens: not just for Christmas, but it’s a good time to dive into his works if you haven’t already.

Is Dickens part of your regular holiday reading? Who are some of your other favorite authors to read at this time of year?

What Is Nature (Poetry) For?

I’ve been pondering this question thanks to an excellent conference my husband and I attended in Stamford in the middle of November: New Networks for Nature. This is the third year my husband (a teaching associate in the biology department at the University of Reading) has participated, and the second year in a row I’ve chosen one day to go. Last year I had the privilege of seeing some truly phenomenal nature writers. Dave Goulson spoke about his efforts to protect bumblebees; Helen Macdonald gave a reading from H is for Hawk; and Paul Evans and Mark Cocker were on a panel about being Guardian country diarists.

This year one of the conference highlights was a debate between Guardian journalist and rewilding proponent George Monbiot (Feral) and Tony Juniper (What Has Nature Ever Done for Us?), former head of Friends of the Earth. The topic: Is nature an economic resource or a thing of intrinsic value? Both gentlemen came out swinging and were at their most convincing.

Unless we make an economic case for preserving nature (pollinators, hydroelectric power, ecotourism), Juniper believes, we will lose it. If we reframe our approach to play on bastard politicians’ turf, Monbiot counters, we’ve already lost our integrity. Nature is worth saving for its own sake; the problem is not our arguments but our lack of power.

I tended to agree with Juniper: we aren’t winning the conservation debate in any other way, so why not introduce financial incentives? This doesn’t stop us from appreciating nature for aesthetic and spiritual reasons; it’s just another strategy.

I amused myself by imagining the opponents as a solitary noble knight waving the flag of idealism (Monbiot) and a new Noah packing nature into a money-papered Trojan horse to trick the pesky government (Juniper).

Male house sparrow. Courtesy of Chris Foster

If these two, in a roundabout way, pondered what nature is for, the previous session had asked more specifically what nature poetry is for. Led by Ruth Padel, one of my favorite poets, the roster also included Jo Shapcott and Pascale Petit. Each read from her work for 15 minutes and then together they answered audience questions as a panel.

I’d never heard of Petit but ended up loving her poems – they were the highlight of my day. One was about the piece of land her mother left her in France; she asked herself in what sense she could possess the place, and soon realized that it was really a pair of resident kingfishers who owned it. She writes around her difficult childhood, imagining a father who could never be cruel to birds – but then picturing him polishing off an ortolan bunting as his last meal, as Mitterrand was said to do. Along with birds, big cats provide many of the metaphors in her work, including Aramis, a black jaguar in the Paris Zoo, and the jaguar corridor in Belize.

Padel read “The Alligator’s Great Need and Great Desire,” followed by several poems from The Mara Crossing that she had written for members of the conference steering committee, such as one about storm petrels off the Skelligs and a snippet of biographical verse about Audubon. The lovely “Nocturne” commemorates nightly jellyfish migration, a “ghostly flotilla.”

She also read one that she said was the closest she gets to an angry poem: “The Forest, the Corrupt Official and a Bowl of Penis Soup” (from 2004’s The Soho Leopard), on the absurdity of killing rare animals – in this case the tiger – so their parts can be used in medicine or cuisine. Her final reading, from memory, was “Tiger Drinking at Forest Pool”; I nearly teared up when she spoke of “Sadness healed. Haven, in the mind, // To anyone hurt by littleness.”

Shapcott read two series of wildlife-themed poems. The first set, commissioned by Padel for the Zoological Society of London, was about the slender loris, which is also suffering from its use in traditional medicine as well as habitat loss. The second was a sequence about beekeeping, from the perspective of a woman who has just been left by a beekeeper. “Telling the Bees” reflects the folk belief that you have to inform bees of major events or they will leave; it ends “he’s gone, honeys; now you’re mine.” As the poem cycle continues, the hive becomes incorporated into her body until she can’t be separated from the bees.

Padel prefaced the discussion by asking how poetry should be in the face of extinctions and the destruction of the planet. She believes a sophistication of voice and expression is required; it’s not a matter of grabbing people by the lapels and saying “LOOK AT THIS,” but of putting the details together and being a witness.

Buff-tailed bumblebee. Courtesy of Chris Foster.

Shapcott echoed her with Heidegger’s query – what is the poet for in a desperate time? She reiterated that the poet should hold up key questions and let them resonate in people’s imaginations, not force-feed answers. Petit added that in her poetry birds are metaphors for the exploitation for the weak. All three agreed poetry is about embodiment, sensory response to the world – essential since we live least in our bodies of any species, Shapcott observed.

The theme of this year’s conference was “Place and Belonging,” and it struck me that all three poets were responding to the idea that nature belongs to us and can be used like any other possession. Instead, they reply, we should think about the places we belong to, and how we can serve rather than exploit nature. But the key is not to spell that out in polemic verse, but rather to speak of life’s particulars and hope that we manage to point to the universal.

I’ll end with part of a stanza from Padel’s “The Watcher” that seems to reinforce the personal, spiritual value of nature that so much of the conference suggested:

Quest for the sacred. And if I

could track that one stork down

on its winter ground, maybe I’d know

what has become of life and me

and where to go. I’d pour libations, follow

the omen, set up sacrifice

to the god of wayfarers, even pay a call

on the seer who decodes

the flight of birds. I’d prophesy.

![A Christmas Carol: Mr. Fezziwig's Ball. John Leech [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://bookishbeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/a_christmas_carol_-_mr-_fezziwigs_ball.jpg?w=229&h=300)