Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

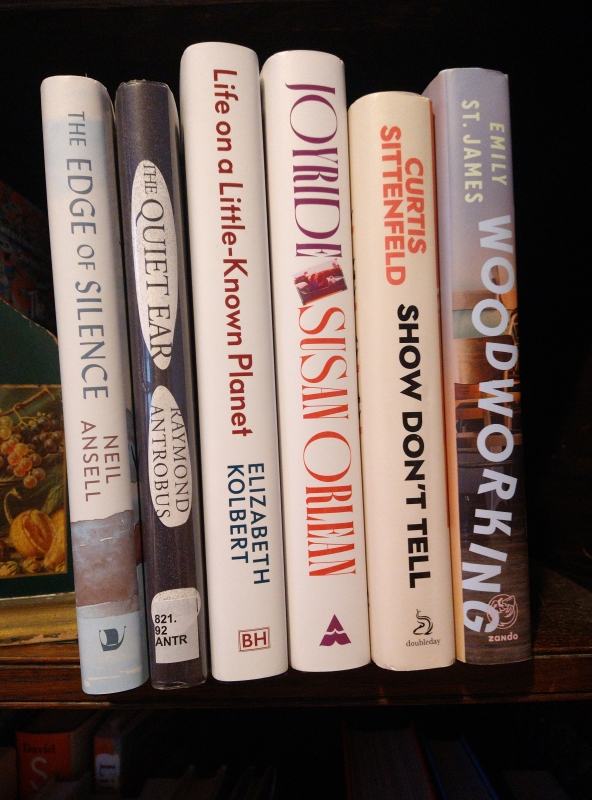

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Book Serendipity, Mid-June through August

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A description of the Y-shaped autopsy scar on a corpse in Pet Sematary by Stephen King and A Truce that Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews.

- Charlie Chaplin’s real-life persona/behaviour is mentioned in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus and Greyhound by Joanna Pocock.

- The manipulative/performative nature of worship leading is discussed in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and Jarred Johnson’s essay in the anthology Queer Communion: Religion in Appalachia. I read one scene right after the other!

- A discussion of the religious impulse to celibacy in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- Hanif Kureishi has a dog named Cairo in Shattered; Amelia Thomas has a son by the same name in What Sheep Think About the Weather.

- A pilgrimage to Virginia Woolf’s home in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd.

- Water – Air – Earth divisions in the Nature Matters (ed. Mona Arshi and Karen McCarthy Woolf) and Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthologies.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- Inappropriate sexual comments made to female bar staff in The Most by Jessica Anthony and Isobel Anderson’s essay in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology.

- Charlie Parker is mentioned in The Most by Jessica Anthony and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The metaphor of an ark for all the elements that connect one to a language and culture was used in Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis, which I read earlier in the year, and then again in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- A scene of first meeting their African American wife (one of the partners being a poet) and burning a list of false beliefs in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The Kafka quote “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us” appears in Shattered by Hanif Kureishi and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd. They also both quote Dorothea Brande on writing.

- The simmer dim (long summer light) in Shetland is mentioned in Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield and Sally Huband’s piece in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology (not surprising as they both live in Shetland!).

- A restaurant applauds a proposal or the news of an engagement in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Likeness by Samsun Knight.

- Noticing that someone ‘isn’t there’ (i.e., their attention is elsewhere) in Woodworking by Emily St. James and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and Leaving Church by Barbara Brown Taylor – which involves her literally leaving Atlanta to be the pastor of a country church – at the same time. (I was also reading Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam.)

- A mention of an adolescent girl wearing a two-piece swimsuit for the first time in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han, and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A discussion of John Keats’s concept of negative capability in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A mention of JonBenét Ramsey in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and the new introduction to Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A character drowns in a ditch full of water in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A woman who’s dying of stomach cancer in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A woman’s genitals are referred to as the “mons” in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- A girl doesn’t like her mother asking her to share her writing with grown-ups in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A girl is not allowed to walk home alone from school because of a serial killer at work in the area, and is unprepared for her period so lines her underwear with toilet paper instead in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A character named Stefan in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- A father who is a bad painter in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce.

- The goddess Minerva is mentioned in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A woman finds lots of shed hair on her pillow in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević and The Dig by John Preston.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- The narrator ponders whether she would make a good corpse in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano. The former concludes that she would, while the latter struggles to lie still during savasana (“Corpse Pose”) in yoga – ironic because she has terminal ALS.

- Harry the cat in The Wedding People by Alison Espach; Henry the cat in Calls May Be Recorded by Katharina Volckmer.

- The protagonist has a blood test after rapid weight gain and tiredness indicate thyroid problems in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- It’s said of an island that nobody dies there in Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave by Mariana Enríquez and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- A woman whose mother died when she was young and whose father was so depressed as a result that he was emotionally detached from her in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

- There’s a ghost in the cellar in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević, The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- Mention of harps / a harpist in The Wedding People by Alison Espach, The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce, and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- “You use people” is an accusation spoken aloud in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- Let’s not beat around the bush: “I want to f*ck you” is spoken aloud in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins; “Want to/Wanna f*ck?” is also in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller.

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

- A shawl is given as a parting gift in How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell and one story of What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- The author has Long Covid in Alec Finlay’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and Pluck by Adam Hughes.

- An old woman applies suncream in Kate Davis’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell.

- There’s a leper colony in What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- There’s a missionary kid in South America in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- A teen brother and sister wander the woods while on vacation with their parents in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- Using a famous fake name as an alias for checking into a hotel in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Seascraper by Benjamin Wood.

- A woman punches someone in the chest in the title story of Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?