Blog Tour: The Secret Life of Mrs. London by Rebecca Rosenberg

I have a weakness for novels about history’s famous wives, whether that’s Zelda Fitzgerald, the multiple Mrs. Hemingways, or the First Ladies of the U.S. presidents. A valuable addition to that delightful sub-genre of fiction is The Secret Life of Mrs. London, the recent debut novel by California lavender farmer Rebecca Rosenberg. I’m pleased to be closing out the blog tour today with a mini review. So many thorough reviews have already appeared that I won’t attempt to compete with them, but will just share a few reasons why I found this a worthwhile read.

I have a weakness for novels about history’s famous wives, whether that’s Zelda Fitzgerald, the multiple Mrs. Hemingways, or the First Ladies of the U.S. presidents. A valuable addition to that delightful sub-genre of fiction is The Secret Life of Mrs. London, the recent debut novel by California lavender farmer Rebecca Rosenberg. I’m pleased to be closing out the blog tour today with a mini review. So many thorough reviews have already appeared that I won’t attempt to compete with them, but will just share a few reasons why I found this a worthwhile read.

Set in 1915 to 1917, this is the story of the last couple of years of Jack London’s life, narrated by his second wife, Charmian, who was five years his senior. The novel opens in California at the Londons’ Beauty Ranch and Wolf House complex and also travels to Hawaii and New York City. Events are condensed and fictionalized, but true to life – thanks to the biography Charmian wrote of Jack and the author’s access to her journals and their letters.

Here are a few things I particularly liked about the novel:

A fantastic opening scene: September 1915: Charmian decides to fix Jack’s hangover with strong coffee and a boxing match – with her! – while their Japanese servant, Nakata, and their house guests look on with bemusement. “Nothing breathes vigor into a marriage like a boxing match.”

A fantastic opening scene: September 1915: Charmian decides to fix Jack’s hangover with strong coffee and a boxing match – with her! – while their Japanese servant, Nakata, and their house guests look on with bemusement. “Nothing breathes vigor into a marriage like a boxing match.”- A glimpse into Jack London’s lesser-known writings: I’ve only ever read White Fang and The Call of the Wild, as a child. But in addition to his adventure stories he also wrote realist/sociopolitical novels and science fiction. At the time when the novel opens, he’s working on The Star Rover. This has inspired me to look into some of his more obscure work.

- The occasional clash of the spouses’ ambitions: Charmian considers it her duty to hold Jack to his promise of writing 1,000 words a day. However, she is an aspiring writer herself, and she often needles Jack to talk to his publisher about accepting her books. (She eventually published two travel books, The Log of the Snark (1915), about their years sailing the Pacific, and Our Hawaii (1917), as well as her biography of her late husband, The Book of Jack London, in 1921.)

- Charmian’s longing for motherhood: Jack London had an ex-wife and two daughters, Joan and Becky. In 1910 Charmian gave birth to a daughter, Joy, who soon died. Even though she is 43 by the time the book opens, she still wants to try again for a baby. Her hopes and disappointments are a poignant part of the story.

- Cameos from other historical figures: Harry Houdini and his wife, especially, have a large part to play in the novel, particularly in the last quarter.

I wasn’t so keen on the sex scenes, which are fairly frequent. However, I can recommend this to fans of Nancy Horan’s work.

My rating:

The Secret Life of Mrs. London was published by Lake Union Publishing on January 30th. I read an e-copy via NetGalley.

Blog Tour Review: Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng

I’m delighted to be helping to close out the UK blog tour for Little Fires Everywhere. Celeste Ng has set an intriguing precedent with her first two novels, 2014’s Everything I Never Told You and this new book, the UK release of which was brought forward by two months after its blockbuster success in the USA. The former opens “Lydia is dead. But they don’t know this yet.” The latter starts “Everyone in Shaker Heights was talking about it that summer: how Isabelle, the last of the Richardson children, had finally gone around the bend and burned the house down.” From the first lines of each novel, then, we know the basics of what happens: Ng doesn’t write mysteries in the generic sense. She doesn’t want us puzzling over whodunit; instead, we need to ask why, examining motivations and the context of family secrets.

Little Fires Everywhere opens in the summer of 1997 in the seemingly idyllic planned community of Shaker Heights, Ohio: “in their beautiful, perfectly ordered city, […] everyone got along and everyone followed the rules and everything had to be beautiful and perfect on the outside, no matter what mess lay within.” That strict atmosphere will take some getting used to for single mother Mia Warren, a bohemian artist who has just moved into town with her fifteen-year-old daughter, Pearl. They’ve been nomads for Pearl’s whole life, but Mia promises that they’ll settle down in Shaker Heights for a while.

Little Fires Everywhere opens in the summer of 1997 in the seemingly idyllic planned community of Shaker Heights, Ohio: “in their beautiful, perfectly ordered city, […] everyone got along and everyone followed the rules and everything had to be beautiful and perfect on the outside, no matter what mess lay within.” That strict atmosphere will take some getting used to for single mother Mia Warren, a bohemian artist who has just moved into town with her fifteen-year-old daughter, Pearl. They’ve been nomads for Pearl’s whole life, but Mia promises that they’ll settle down in Shaker Heights for a while.

Mia and Pearl rent a duplex owned by Elena Richardson, a third-generation Shaker resident, local reporter and do-gooder, and mother of four stair-step teens. Pearl is fascinated by the Richardson kids, quickly developing an admiration of confident Lexie, a crush on handsome Trip, and a jokey friendship with Moody. Izzy, the youngest, is a wild card, but in her turn becomes enraptured with Mia and offers to be her photography assistant. Mia can’t make a living just from her art, so takes the occasional shift in a Chinese restaurant and also starts cleaning the Richardsons’ palatial home in exchange for the monthly rent.

The novel’s central conflict involves a thorny custody case: Mia’s colleague at the restaurant, Bebe Chow, was in desperate straits and abandoned her infant daughter, May Ling, at a fire station in the dead of winter. The baby was placed with the Richardsons’ dear friends and neighbors, the McCulloughs, who yearn for a child and have suffered multiple miscarriages. Now Bebe has gotten her life together and wants her daughter back. Who wouldn’t want a child to grow up in the comfort of Shaker Heights? But who would take a child away from its mother and ethnic identity? The whole community takes sides, and the ideological division is particularly clear between Mia and Mrs. Richardson (as she’s generally known here).

For all that Shaker Heights claims to be colorblind, race and class issues have been hiding under the surface and quickly come to the forefront. Mrs. Richardson’s journalistic snooping and Mia’s warm words – she seems to have a real knack for seeing into people’s hearts – are the two driving forces behind the plot, as various characters decide to take matters into their own hands and make their own vision of right and wrong a reality. Fire is a potent, recurring symbol of passion and protest: “Did you have to burn down the old to make way for the new?” Whether they follow the rules or rebel, every character in this novel is well-rounded and believable: Ng presents no clear villains and no easy answers.

The U.S. cover

There are perhaps a few too many coincidences, and a few metaphors I didn’t love, but I was impressed at how multi-layered this story is; it’s not the simple ethical fable it might at first appear. There are so many different shards in its mosaic of motherhood: infertility, adoption, surrogacy, pregnancy, abortion; estrangement, irritation, longing, pride. “It came, over and over, down to this: What made someone a mother? Was it biology alone, or was it love?” Ng asks. I also loved the late-1990s setting. It’s a time period you don’t often encounter in contemporary fiction, and Ng brings to life the ambiance of my high school years in a way I found convincing: the Clinton controversy, Titanic, the radio hits playing at parties, and so on.

Each and every character earns our sympathy here – a real triumph of characterization, housed in a tightly plotted and beautifully written novel you’ll race through. This may particularly appeal to readers of Curtis Sittenfeld, Pamela Erens and Lauren Groff, but I’d recommend it to any literary fiction reader. One of the best novels of the year.

My rating:

Little Fires Everywhere was published by Little, Brown UK on November 9th. My thanks to Grace Vincent for the review copy.

Blog Tour & Giveaway: The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities

I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: A Yearbook of Forgotten Words by Paul Anthony Jones, which will be published in the UK by Elliott & Thompson on Thursday, October 19th.

I started reading these delightful daily doses of etymology last week, and plan to keep the book at my bedside for the whole of the year to come. By happy coincidence, today is also my birthday, so (if I may so flatter myself) in joint honor of the occasion plus the book’s impending publication, Elliott & Thompson have kindly offered a giveaway copy to one UK-based reader.

Enjoy today’s entry, and leave a comment if you’d like to be in the running for the giveaway. I will choose the winner at random at the end of Saturday the 21st and notify them via e-mail.

14 October

Parthian (adj.) describing or akin to a shot fired while in retreat

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066. Exhausted and depleted from fighting the Battle of Stamford Bridge just nineteen days earlier, the English King Harold’s forces were eventually overcome by those of the invading Norman King William when they began to implement an ingenious and effective tactic. Reportedly, William’s troops pretended to flee from the battle in panic, and as their English attackers pursued them, the Normans suddenly turned back and resumed fighting.

The Normans and their allies, observing that they could not overcome an enemy which was so numerous and so solidly drawn up, without severe losses, retreated, simulating flight as a trick . . . Suddenly the Normans reined in their horses, intercepted and surrounded [the English] and killed them to the last man.

William of Poitiers, Gesta Guillelmi (c.1071)

The Normans weren’t the first to use such a tactic; fighters in ancient Parthia, a region of northeast Iran, were known to continue firing arrows at their enemies while retreating from the battlefield. The ploy proved so effective that the adjective Parthian ultimately came to be used of any shot or attack employed while in retreat, or in the dying moments of an engagement. In that sense, the word first appeared in English in the mid seventeenth century, but while the technique they employed remained familiar, the Parthians themselves did not. Ultimately, the word Parthian became corrupted, and steadily drifted closer to a much more familiar term – so that today this kind of last-minute attack or sally is typically known as a parting shot.

Blog Tour: The Floating Theatre by Martha Conway (Review & Excerpt)

The Floating Theatre, Martha Conway’s fourth novel, opens with a bang – literally. April 1838: twenty-two-year-old seamstress May Bedloe and her cousin, the actress Comfort Vertue, are on the St. Louis-bound steamboat Moselle when its boilers explode (a real-life disaster) and they must evacuate posthaste. Afterwards Comfort accepts a new role giving abolitionist speeches; May takes her sewing skills on board Captain Hugo Cushing’s Floating Theatre, where she will be a Jill of all trades: repairing costumes, printing tickets, publicizing the show in towns along the Ohio River where they moor for performances, and so on.

Conway gives a vivid sense of nineteenth-century theater life, both off-stage and on-, including just the right amount of historical detail so you can picture everything that’s going on. May is a delightfully no-nonsense narrator – she’d probably be diagnosed with Asperger’s nowadays for her literal approach and her initial inability to lie – and she’s supported by a wonderfully Dickensian cast of actors and crew members. The gripping plot takes on a serious dimension as May, too, gets drawn into the abolition movement: soon she’s helping to deliver runaway slaves from one side of the river to freedom on the other.

Conway gives a vivid sense of nineteenth-century theater life, both off-stage and on-, including just the right amount of historical detail so you can picture everything that’s going on. May is a delightfully no-nonsense narrator – she’d probably be diagnosed with Asperger’s nowadays for her literal approach and her initial inability to lie – and she’s supported by a wonderfully Dickensian cast of actors and crew members. The gripping plot takes on a serious dimension as May, too, gets drawn into the abolition movement: soon she’s helping to deliver runaway slaves from one side of the river to freedom on the other.

In America this was published as The Underground River, more clearly advertising its Underground Railroad theme. As it happens, I prefer this to Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, a novel to which it will inevitably be compared. (For one thing, Conway has a much more nuanced slave catcher character.) This is terrific historical fiction I can heartily recommend.

My rating:

The Floating Theatre was released in the UK by Zaffre, an imprint of Bonnier Publishing, on June 15th. My thanks to Imogen Sebba for the free copy for review.

An exclusive extract from The Floating Theatre:

Two figures were standing on the lower deck at the stern of the boat. One of them might have been Hugo, but as I got closer I saw that the other one was certainly not Helena—it was Thaddeus Mason, eating popcorn from a red-and-white striped bag.

“What ho, May!” Thaddeus called out when he saw me, as if he were practicing for a nautical part. I noticed he no longer wore his arm in a sling. The other man turned as I came up the gangplank; like Thaddeus, he wore his hair long, but his coloring was darker and he was half a head taller. There was a band of black crepe around his straw hat, and his shirtsleeves were rolled up past his elbows. Thaddeus introduced me.

“Captain Hugo Cushing,” the man said in a British accent, touching his hat.

“May and I were on the Moselle together,” Thaddeus told him—was that to be his introduction for me from now on? But he went on to say that Hugo’s sister Helena had been on the Moselle, too. “Do you remember the singer at dinner? Helena Cushing, of Hugo and Helena’s Floating Theatre?” Thaddeus took off his hat. “Sadly, she was not as fortunate as we were.”

I looked at Hugo and tried to think of something kind to say. I remembered the singer in her pink dress with the light shining behind her.

“The captain let her on to perform,” Hugo said. “We often made a few extra dollars this way. She was going to get off at the stop after Fulton. I was just pushing off to meet up with her there when the sky broke up with the explosion.”

“Oh,” I said. “That is—that’s very bad…” I trailed off awkwardly, but Thaddeus came in with a string of platitudes, which he spoke with great conviction and aplomb—a terrible disaster, an immense misfortune, the captain was a dastardly fellow.

“Where do you go?” I asked Hugo when Thaddeus finished. “Or do you stay here?”

He looked at me blankly.

“On this boat. Your theatre. Where do you perform?”

“Oh, well then, down along the Ohio, of course. We dock at a different town every day, put on a show, and then the next morning pull up and head for the next town. We go all the way to the Mississippi playing towns until the weather turns. Then we get pushed back up the river—I hire a steamer.” I could see that his boat, a flatboat, had no steam power of its own. “Fourth year at it,” he told me. “My sister and I put it all together. But now…” He made a gesture which I took to understand that for him, like me, his old partnership was over.

“And if that weren’t enough, his boat was damaged by the explosion,” Thaddeus added. “The captain was just telling me. Part of the Moselle’s paddle box shot in like a cannonball.”

“Even worse, my leather boat pump got punctured,” Hugo said. “Don’t know how I’m going to fix it, and a new one costs twenty dollars more than I have.”

“How much does a new one cost?” I asked.

He looked at me as if I were a fool. “Twenty dollars.”

“Where is your company?” Thaddeus asked him. “Maybe you could take up a collection.”

“They skittered off into town. Probably drinking their way into even more uselessness. Damn actors. Excuse me,” he said, but I wasn’t sure he meant the apology for me since he was looking out at the river. I wasn’t offended in any case. I had seen actors humiliate themselves in a variety of ways over the years.

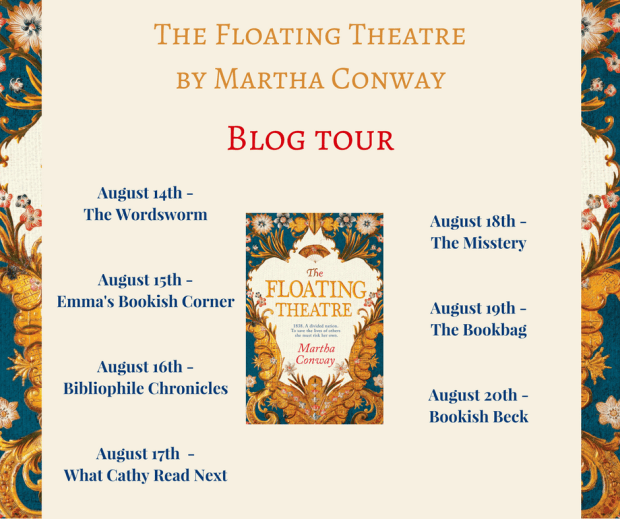

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the blog tour for The Floating Theatre. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared.

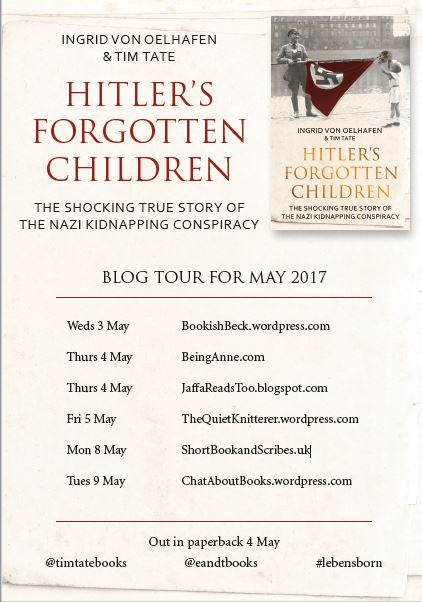

Giveaway: Hitler’s Forgotten Children

Tomorrow Elliott & Thompson are releasing the paperback edition of Hitler’s Forgotten Children by Ingrid von Oelhafen and Tim Tate, a powerful first-person account from a child of the Lebensborn: the Nazis’ program to create an Aryan master race.

The publisher has kindly offered a free copy to one of my readers.

Here’s a bit more information about the book, adapted from the press release:

Forcibly adopted into a Nazi family as part of the Lebensborn program, Ingrid’s heartbreaking story is a quest for identity and an important historical document touching on the untold stories of thousands like her.

By the 1940s, Himmler’s breeding program had failed to provide adequate numbers of ‘racially pure and healthy’ children, so Lebensborn sought to boost the flagging German population by sinister means. Children in the occupied territories were examined and any exhibiting ‘Aryan’ qualities were forcibly taken from their parents to be raised by the regime.

In 1942 Erika, a baby girl from Yugoslavia, was examined by the Nazi occupiers, declared an ‘Aryan’ and removed from her mother. Her true identity erased, she became Ingrid von Oelhafen. Later, as Ingrid began to uncover her true identity, the full scale of the Lebensborn scheme became clear – including the kidnapping of up to half a million babies like her, and the deliberate murder of children born into the program who were deemed ‘substandard’.

We learn of Ingrid’s subsequent troubled childhood in Germany; first during the war, then a harrowing escape from the GDR, time in children’s homes and the shock of discovering as a teenager that she was adopted. Later, the search for the truth took her to Nuremberg Trials records and, ultimately, back to Yugoslavia, where she discovered the full story: the Nazis substituted ‘Ingrid’ with another child who was raised as ‘Erika’ by her family.

And here’s an exclusive extract:

Cilli, German-occupied Yugoslavia, 3–7 August 1942

The schoolyard was crowded. Hundreds of women – young and old – clutched the hands of their children and found what space they could in the packed courtyard. Nearby, Wehrmacht soldiers, rifles slung over their shoulders, looked on as the families slowly drifted in from towns and villages across the area. These women had been summoned by their new German masters, ordered to bring their children to the school for ‘medical tests’. Upon arrival they were arrested and told to wait. Otto Lurker, commander of the police and security services for the region, watched relaxed and impassive – his hands resting comfortably in his pockets – as the yard filled with families. Once, Lurker had been Hitler’s gaoler: now he was the Führer’s leading henchman in Lower Styria. He held the rank of SS-Standartenführer – the paramilitary equivalent of a full colonel in the army – but that summer’s morning he was casually dressed in a two-piece civilian suit.

Among them was a family from the nearby village of Sauerbrunn. Johann Matko came from a family of known partisans: his brother, Ignaz, had been one of those lined up and shot against the wall of Cilli prison in July. Johann had been dragged off to Mauthausen concentration camp. After seven months in the camp he was allowed to return home to his wife, Helena, and their three children: eight-year-old Tanja, her brother Ludvig – then six – and nine-month-old baby Erika. When all the families were accounted for, an order was given to separate them into three groups – one each for the children, the women, and the men.

Under Lurker’s direction the soldiers moved in and pulled children from the grasp of their mothers; a local photographer, Josip Pelikan, recorded the harrowing scene for the Reich’s obsessive archivists. His rolls of film captured the fear and alarm of women and children alike: his shots included scores of toddlers held in low pens of straw inside the school buildings. As the mothers waited outside, Nazi officials began a cursory examination of the children.

Working with charts and clipboards, they painstakingly noted each child’s facial and physical characteristics. These, though, were not ‘medical tests’ as any doctor would know them: instead they were crude assessments of ‘racial value’ which assigned each youngster to one of four categories. Those who met Himmler’s strict criteria for what a child of true German blood should look like were placed in Category 1 or 2: this formally registered them as potentially useful additions to the Reich population.

By contrast, any hint or trace of Slavic features – and certainly any sign of ‘Jewish heritage’– consigned a child to the lowest racial status of Categories 3 and 4. Thus branded as Untermensch, their value was no more than future slave labour for the Nazi state. By the following day this rudimentary sifting had finished. Those children deemed racially worthless were handed back to their families. But 430 other youngsters, from young babies to twelve-year-old boys and girls, were taken away by their captors. Marshalled by nurses from the German Red Cross, they were packed into trains and transported across the Yugoslavian border to an Umsiedlungslager – or transit camp – at Frohnleiten, near the Austrian town of Graz.

They did not stay long in this holding centre. By September 1942, a further selection had been made – this time by trained ‘race assessors’ from one of the myriad organisations established by Himmler to preserve and strengthen the pool of ‘good blood’. Noses were measured and compared to the official ideal length and shape; lips, teeth, hips and genitals were likewise prodded, poked and photographed to sort the genetically precious human wheat from the less-valuable chaff.

This finer, more rigorous sieving re-assigned the captives within the four racial categories. Older children newly listed in Categories 3 or 4 were shipped off to re-education camps across Bavaria in the heartland of Nazi Germany. The best of the younger ones in the top two categories would – in time – be handed over to a secretive project run by the Reichsführer himself. Its name was Lebensborn and among the infants assigned to its care was nine-month-old Erika Matko.

If you’re interested in winning a paperback copy of Hitler’s Forgotten Children, simply leave a comment to that effect below. The competition will be open through the end of Friday the 12th and I will choose a winner at random on Saturday the 13th (announced via the comments and a personal e-mail). Sorry, U.K. entries only. Good luck!

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the paperback release blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features will be appearing soon.

Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Ed Yong’s I Contain Multitudes

Ed Yong is a London-based science writer for The Atlantic and is part of National Geographic’s blogging network. I had trouble believing that I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes within Us and a Grander View of Life is his first book; it’s so fluent and engaging that it immediately draws you into the microbial world and keeps you marveling at its strange yet fascinating workings. Yong writes like a journalist rather than a scientist, and that’s a good thing: with an eye to the average reader, he uses a variety of examples and metaphors, intersperses personal anecdotes of visiting researchers at their labs or in the field, and is careful to recap important facts in a lucid way.

The book opens with a visit to San Diego Zoo (see the exclusive extract following my review), where we meet Baba the pangolin. But “Baba is not just a pangolin. He is also a teeming mass of microbes,” Yong explains. “Some of them live inside him, mostly in his gut. Others live on the surface of his face, belly, paws, claws, and scales.” Believe it or not, but we are roughly half and half human cells and microbial cells, making each of us – like all creatures – more of an ecosystem (another term is “holobiont”) than a single entity.

Microbes vary between species but also within species, so each individual’s microbiome in some ways reflects a unique mixture of genes and experiences. This is why people’s underarms smell subtly different, and how hyenas use their scent glands to convey messages. The microbiome may well be tailored to different creatures’ functions, so researchers at San Diego Zoo are testing swabs from their animals to see if there could be discernible signatures for burrowing or flying activities, or for disease. I was struck by the breadth of species considered here: not just mammals, but also invertebrates like beetles, cicadas, and squid – my entomologist husband would surely be proud. The “Us” in the subtitle is thus used very inclusively to speak of the way that microbes live in symbiosis with all living things.

I love the textured dust jacket too.

If I were to boil down Yong’s book to one message, it’s that microbes are not simply “bad” or “good” but have different roles depending on the context and the host. You can hardly dismiss all bacteria as germs that must be eradicated when there are thousands of benign species in your gut (versus fewer than 100 kinds that cause infectious diseases). If it weren’t for the microbes passed on to us at birth, we wouldn’t be able to digest the complex sugars in our mothers’ milk. Other creatures rely on bacteria to help them develop to adulthood, like the tube worms that thrive on Navy ship hulls at Pearl Harbor.

Yet Yong feels too little attention is given to beneficial microbes, and in many cases we continue the campaign to rid ourselves of them through overuse of antibiotics and taking cleanliness to unhelpful extremes. “We have been tilting at microbes for too long, and created a world that’s hostile to the ones we need,” he asserts.

The book is full of lines like that one that combine a nice turn of phrase and a clever literary allusion. In the title alone, after all, you have references to Walt Whitman (“I contain multitudes” is from his “Song of Myself”) and Charles Darwin (“there is grandeur in this view of life” is part of the closing sentence in his On the Origin of Species). Yong also sets up helpful analogies, comparing the immune system to a thermostat and antibiotics to “shock-and-awe weapons … like nuking a city to deal with a rat.”

History and future are also brought together very effectively, with the narrative looking backwards to Leeuwenhoek’s early microscope work and Pasteur and Koch’s germ theory, but also forwards to the prospects that current research into microbes might enable: eliminating elephantiasis, protecting frogs from deadly fungi via probiotics in the soil, fecal microbiota transplants to cure C. diff infections, and so on.

The possibilities seem endless, and this is a book that will keep you shaking your head in amazement. I’d liken Yong’s style to David Quammen’s or Rebecca Skloot’s. His clear and intriguing science writing succeeds in inspiring wonder at the natural world and at the bodies that carry us through it.

With thanks to Joe Pickering at The Bodley Head for the review copy.

My rating:

An exclusive extract from “PROLOGUE: A TRIP TO THE ZOO”

I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong

(The Bodley Head)

All of us have an abundant microscopic menagerie, collectively known as the microbiota or microbiome.1 They live on our surface, inside our bodies, and sometimes inside our very cells. The vast majority of them are bacteria, but there are also other tiny organisms including fungi (such as yeasts) and archaea, a mysterious group that we will meet again later. There are viruses too, in unfathomable numbers – a virome that infects all the other microbes and occasionally the host’s cells. We can’t see any of these minuscule specks. But if our own cells were to mysteriously disappear, they would perhaps be detectable as a ghostly microbial shimmer, outlining a now-vanished animal core.2

In some cases, the missing cells would barely be noticeable. Sponges are among the simplest of animals, with static bodies never more than a few cells thick, and they are also home to a thriving microbiome.3 Sometimes, if you look at a sponge under a microscope, you will barely be able to see the animal for the microbes that cover it. The even simpler placozoans are little more than oozing mats of cells; they look like amoebae but they are animals like us, and they also have microbial partners. Ants live in colonies that can number in their millions, but every single ant is a colony unto itself. A polar bear, trundling solo through the Arctic, with nothing but ice in all directions, is completely surrounded. Bar-headed geese carry microbes over the Himalayas, while elephant seals take them into the deepest oceans. When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon, they were also taking giant steps for microbe-kind.

When Orson Welles said ‘We’re born alone, we live alone, we die alone’, he was mistaken. Even when we are alone, we are never alone. We exist in symbiosis – a wonderful term that refers to different organisms living together. Some animals are colonised by microbes while they are still unfertilised eggs; others pick up their first partners at the moment of birth. We then proceed through our lives in their presence. When we eat, so do they. When we travel, they come along. When we die, they consume us. Every one of us is a zoo in our own right’– a colony enclosed within a single body. A multi-species collective. An entire world.

Footnotes

- In this book, I use the terms ‘microbiota’ and ‘microbiome’ interchangeably. Some scientists will argue that microbiota means the organisms themselves, while microbiome refers to their collective genes. But one of the very first uses of microbiome, back in 1988, used the term to talk about a group of microbes living in a given place. That definition persists today – it emphasises the ‘biome’ bit, which refers to a community, rather than the ‘ome’ best, which refers to the world of genomes.

- This imagery was first used by the ecologist Clair Folsome (Folsome, 1985).

- Sponges: Thacker and Freeman, 2012; placozoans: personal communication from Nicole Dubilier and Margaret McFall-Ngai.

My gut feeling: This book is a fine example of popular science writing, and has much to teach us about the everyday workings of our bodies. It’s one of my three favorites from the shortlist.

See also: Paul’s review at Nudge

Shortlist strategy: Tomorrow I’ll post a quick response to David France’s How to Survive a Plague, and on Sunday we will announce our shadow panel winner.

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

And if you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to one of the shortlist events being held this Saturday and Sunday.

Blog Tour: My Mourning Year by Andrew Marshall

Andrew G. Marshall is the author of 18 self-help books about relationships. He has written for newspapers, appeared on television and radio programs, and worked as a marriage therapist. However, he has shared little about his own experience of relationships until now. Twenty years have passed since the death of his long-term partner, Thomas Hartwig. Sharing this diary of Thom’s death with several friends and family members who’d suffered recent bereavements seemed to help, so he’s hoping that in book form it can be of wider benefit to those who are in the midst of grief.

Marshall met Thom, then the headmaster of a German language school, on a holiday to Spain in September 1989. They alternated between Germany and England every other weekend for years, and in 1995 Thom finally relocated to join Marshall near Brighton. Thom had plans to start an interior design business, but fell ill just six months later. By early 1997, he had a diagnosis of liver failure and was given weeks to live. They traveled to Germany to get Thom a second opinion and, despite his resolution to die back in England, he breathed his last at the German hospital on March 9th, aged 43.

The above constitutes a brief Part One, while the rest of the book recounts the first full year after Thom’s death. Marshall tracks the changes in several areas of his life:

Family Life: “People become counselors to make sense of their difficult families, and of course I am no exception,” Marshall notes. He grew up in a conservative middle-class family in Bedford and didn’t come out until he was nearly 30. Hugely disappointed that his parents and sister didn’t make it to Thom’s memorial service, Marshall moves from not talking to his family at all to making tentative overtures of reconciliation. There’s a particularly touching scene where he confronts his parents about the way they repressed emotion while he was growing up and hears the words “I love you” from his father for the first time.

Career: For part of his mourning year, Marshall worked on the Agony television program as an “agony uncle.” He took a break from Relate counseling, but continued to write freelance articles, many of them touching on illness and death, and contributed a “Revelations” celebrity profile column to the Independent, in which he interviewed authors and pop stars about life’s turning points. Two of my favorite moments in the book arise from this: Jim Crace (promoting Quarantine) tells how he realized the emptiness of atheism when burying his father; and Carol Shields’s Larry’s Party provides Marshall’s gateway into literary fiction, which he’d never attempted before.

Career: For part of his mourning year, Marshall worked on the Agony television program as an “agony uncle.” He took a break from Relate counseling, but continued to write freelance articles, many of them touching on illness and death, and contributed a “Revelations” celebrity profile column to the Independent, in which he interviewed authors and pop stars about life’s turning points. Two of my favorite moments in the book arise from this: Jim Crace (promoting Quarantine) tells how he realized the emptiness of atheism when burying his father; and Carol Shields’s Larry’s Party provides Marshall’s gateway into literary fiction, which he’d never attempted before.

Home Life: “There is something terribly sad about the clutter we accumulate,” Marshall sighs. “I was loved and I did love, but now all I had was this debris.” Thom moved to England with 87 packing cases; even at the hospital in Germany there were two bags of stuff to look through. Back in England, though Marshall tries to navigate around “Thom-shaped holes” in his life, especially near holidays, he realizes this relationship hasn’t ended: he kisses his lover’s ashes goodnight, and heeds Thom’s late advice to replace the vacuum cleaner. Meanwhile he goes on short vacations, sees friends, dogsits, and even tries counseling – but finds it’s “like watching a conjurer saw a lady in half, but knowing how he does it.”

Spirituality: Marshall has several experiences he has trouble explaining. For instance, at certain points he smells vanilla all around him and chooses to take it as a sign of Thom’s enduring presence – a trace of the vanilla candle that burned beside his deathbed. He also has some psychic messages conveyed, by both friends and strangers, and attends a spiritualist service. But it is an interview with forensics expert Kathy Reichs that helps him to once and for all detach the idea of Thom’s dead body from that of his spirit.

Self-Expression: Writing the “Revelations” column and this diary proved better therapy for Marshall than traditional counseling sessions. Towards the end of this book he also takes an introduction to playwriting course, and in the intervening years several of the plays he has written have been performed around the UK.

Love: After Thom’s death, Marshall was desperate for physical comfort, and temporarily found it with Peter, whom he met at a gay sauna. I admired Marshall’s honesty about this fling; it must have been tempting to excise it from the record to make himself look better. But their relationship never went beyond a few dates. This sad story has a happy coda, though: In 2001 Marshall met Ignacio, who became his civil partner in 2008 and his husband in 2015.

I’ve read many bereavement memoirs, but the diary format makes this one a unique blend of momentous occasions – Princess Diana’s funeral and the preparations for a catered dinner party on the anniversary of Thom’s death – and the challenges of everyday life. I would not hesitate to recommend it to anyone who has experienced or is currently enduring bereavement; it will be reassuring to read about the flux in Marshall’s emotions and see an example of how to rebuild after loss.

Perhaps this is the reality of mourning: you never get over the loss but reassemble the daily minutiae into a new life. At the beginning it feels like a box of flat-pack furniture with the instructions in Swedish, but finally you discover that tab A can slide into slot B. Eventually you own something quite functional – even though there are always a few screws left over and it never looks as good as it does in the catalogue.

Whether the clairvoyants are correct and Thom has become my guardian spirit is not important[;] he is always with me. I have integrated his personality into mine and in that way he lives on through me.

(For more on the author, and Thom, see the book’s website.)

My Mourning Year will be released by RedDoor Publishing on Thursday, April 20th. Thanks to Anna Burtt for the review copy.

My rating:

Blog Tour: Two Voices, One Story

“[B]eing an adoptive parent is like parenting in Technicolor: everything is just a little more intense. This means the highs can be really high, but it also means that the lows are going to be really low. You have to prepare yourself.”

~Sharon Roszia, quoted in A Book about Love, by Jonah Lehrer

Two Voices, One Story is a mother–daughter memoir that splits narration duties between Elaine Rizzo and Amy Masters, the now-teenage daughter she adopted from China in 1999. Elaine’s sections provide the main thread of their story, while Amy’s passages, generally shorter and printed in italics, chime in to give her perspective on various events and relationships that have been important in her life.

Elaine is forthright about her infertility and the miscarriage that led to her decision to adopt. In the late 1990s, China’s one-child policy was still in place, but it was the severe flooding of the Yangtze River that led directly to Amy’s adoption. Thousands died and millions more were displaced. Given the context, it’s not so surprising that baby Amy was left outside a welfare center. She was given the Chinese name Tong Fang – “Copper Child.”

Elaine is forthright about her infertility and the miscarriage that led to her decision to adopt. In the late 1990s, China’s one-child policy was still in place, but it was the severe flooding of the Yangtze River that led directly to Amy’s adoption. Thousands died and millions more were displaced. Given the context, it’s not so surprising that baby Amy was left outside a welfare center. She was given the Chinese name Tong Fang – “Copper Child.”

For me the highlight of the book was Elaine and Lee’s trip to China to pick up Amy. Although they were nervous and disoriented, they experienced the kindness of strangers and responded with compassion of their own, taking along extra toiletries and clothes of different sizes and leaving the surplus with the care center. Amy had bronchitis, one more worry on top of all the paperwork and red tape they had to go through to finalize the adoption.

Back in England, Amy had some behavioral problems that were likely vestiges of her time at the orphanage. She hated noise, especially thunderstorms; she hit herself and others; and she often woke up screaming. Private schooling ensured she wouldn’t get left behind, and there were many happy times with extended family and holidays to Australia and the west coast of Wales, where Elaine and Amy would later settle with Elaine’s second husband.

But life wasn’t always rosy: Amy was strong-willed and uncooperative – perhaps nothing out of the ordinary for a teenager, but still a challenge for her parents. Elaine recalls a social worker telling them “that very often adoptive parents don’t feel like they have the right to tell their child off, or that they think they shouldn’t say or do anything which might upset the child, because they are trying to compensate for what has happened prior to the adoption.”

Lengthy commuting to her job back in England and years-long house renovations demanded much of Elaine’s attention, yet she remained alert to what was going on with Amy. Unfortunately, in her teen years Amy experienced racism from a few schoolmates, including abusive Facebook messages that drove the family to contact the police. Amy herself, though, always comes across as easygoing about being different: “Every Christmas we used to do a Nativity show and I remember being an angel first and then one of the kings, which I suppose was the right role for me because I really do come from the East.”

Even though this is a very quick read, my interest waxed and waned. The telling can be clichéd and sentimental, and I felt too much space was given to banal details that added little to an understanding of the central mother–daughter relationship. This self-published book has a very appealing cover but needs another look from an experienced editor who could fix the fairly frequent typos and punctuation issues and cut out the bullet points (nine pages’ worth) and speech tics like “I will also say…” and “I have to comment…”

I would certainly recommend this book to those who have a personal experience of or interest in adoption, particularly from overseas (for a fictional take on adoption from China, you might also try The Fortunes by Peter Ho Davies, The Red Thread by Ann Hood, and This Must Be the Place by Maggie O’Farrell), as well as to anyone wondering how to parent or educate a child who is in some way different.

I’ll end with some lovely words from Amy:

when my Chinese mum left me outside the gates of the welfare center almost eighteen years ago now, because there was nothing left for me in Tongling, she must have had the desperate hope that I would find a happy life with people who loved me. I can only say that her wish did come true.

My rating:

Two Voices, One Story will be published by Clink Street Publishing on March 21st. Thanks to Rachel Gilbey of Authoright Marketing & Publicity for arranging my free copy for review.

I was pleased to participate in the blog tour for Two Voices, One Story.

The book proper opens with a visit to

The book proper opens with a visit to