Happy 200th Birthday, Charlotte Brontë!

Today marks a big anniversary: the bicentennial of Charlotte Brontë’s birth. I’ve noticed a whole cluster of books being published or reissued in time for her 200th birthday, many of which I’ve reviewed with enjoyment; some of which I’ve sampled and left unfinished. I hope you’ll find at least one book on this list that will take your fancy. There could be no better time for going back to Charlotte Brontë’s timeless stories and her quiet but full life story.

Short Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre

MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD.

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, edited by Tracy Chevalier

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, edited by Tracy Chevalier

A mixed bag. Although there are some very good stand-alone stories (from Tessa Hadley, Sarah Hall, Emma Donoghue and Elizabeth McCracken, as you might expect), ultimately the theme is not strong enough to tie them all together and some seem like pieces the authors had lying around and couldn’t figure out what else to do with. Think about it this way: what story isn’t about romance and the decision to marry?

A few of the tales do put an interesting slant on this age-old storyline by positing a lesbian relationship for the protagonist or offering the possibility of same-sex marriage. Then there are the stories that engage directly with the plot and characters of Jane Eyre, giving Grace Poole’s (Helen Dunmore) or Mr. Rochester’s (Salley Vickers) side of things, putting Jane and Rochester in couples therapy (Francine Prose), or making Jane and Helen Burns part of a post-WWII Orphan Exchange (Audrey Niffenegger). My feeling with these spinoff stories was, I’m afraid, what’s the point? Plus there were a number of others that just felt tedious.

My least favorites were probably by Lionel Shriver (incredibly boring!), Kirsty Gunn (unrealistic, and she gives the name Mr. Rochester to a dog!) and Susan Hill (the title story, but she’s made it about Wallis Simpson – and has the audacity to admit, as if proudly, that she’s never read Jane Eyre!). On the other hand, one particular standout is by Elif Shafak. A Turkish Muslim falls in love with a visiting Dutch student but is so unfamiliar with romantic cues that she doesn’t realize he isn’t equally taken with her.

In Patricia Park’s story, my favorite of all, a Korean girl from Buenos Aires moves to New York City to study English. Park turns Jane Eyre on its head by having Teresa give up on the chance of romance to gain stability by marrying Juan, the St. John Rivers character. I loved getting a glimpse into a world I was entirely ignorant of – who knew there was major Korean settlement in Argentina? This also redoubled my wish to read Park’s novel, Re Jane. She’s working on a second novel set in Buenos Aires, so perhaps it will expand on this story.

The Bookbag reviews

Charlotte Brontë’s Secret Love by Jolien Janzing

by Jolien Janzing

Charlotte and Emily Brontë’s time in Belgium – specifically, Charlotte’s passion for her teacher, Constantin Heger – is the basis for this historical novel. The authoritative yet inviting narration is a highlight, but some readers may be uncomfortable with the erotic portrayal; it doesn’t seem to fit the historical record, which suggests an unrequited love affair.

Sanctuary by Robert Edric

by Robert Edric

Branwell Brontë narrates his final year of life, when alcoholism, mental illness and a sense of disgrace hounded him to despair. I felt I never came to understand Branwell’s inner life, beneath the decadence and all the feeling sorry for himself. This gives a sideways look at Charlotte, Emily and Anne, though the sisters are little more than critical voices here; none of them has a distinctive personality.

Mutable Passions : Charlotte Brontë: A Disquieting Affair by Philip Dent

: Charlotte Brontë: A Disquieting Affair by Philip Dent

Dent focuses on a short period in Charlotte Brontë’s life: with all her siblings dead and Villette near completion, a surprise romance with her father’s curate lends a brief taste of happiness. Given her repeated, vociferous denial of feelings for Mr. Nicholls, I had trouble believing that, just 20 pages later, his marriage proposal would provoke rapturous happiness. To put this into perspective, I felt Dent should have referenced the three other marriage proposals Brontë is known to have received. Overwritten and suited to readers of romance novels than to Brontë enthusiasts, this might work well as a play. Dent is better at writing individual scenes and dialogue than at providing context.

Two Abandonees

I had bad luck with these two novels, which both sounded incredibly promising but I eventually abandoned (along with Yuki Chan in Brontë Country, featured in last month’s Six Books I Abandoned Recently post):

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

Jane Steele is not quite Jane Eyre, though her life seems to mirror that of Brontë’s heroine in most particulars. How she differs is in her violent response to would-be sexual abusers. She’s a feminist vigilante wreaking vengeance on her enemies, whether her repulsive cousin or the vindictive master of “Lowan Bridge” (= Cowan Bridge, Brontë’s real-life school + Lowood, Jane Eyre’s). I stopped reading because I didn’t honestly think Faye was doing enough to set her book apart. “Reader, I murdered him” – nice spin-off line, but there wasn’t enough original material here to hold my attention. (Read the first 22%.)

The Madwoman Upstairs by Catherine Lowell

The Madwoman Upstairs by Catherine Lowell

There was every reason for me to love this novel – awkward American narrator, Oxford setting, Brontë connections aplenty, snarky literary criticism – but I got bored with it. Perhaps it was the first-person narration: being stuck in sarcastic Samantha Whipple’s head means none of the other characters feel real; they’re just paper dolls, with Orville a poor excuse for a Mr. Rochester substitute. I did laugh out loud a few times at Samantha’s unorthodox responses to classic literature (“Agnes Grey is, without question, the most boring book ever written”), but I gave up when I finally accepted that I had no interest in how the central mystery/treasure hunt played out. (Read the first 56%.)

An Excellent Biography

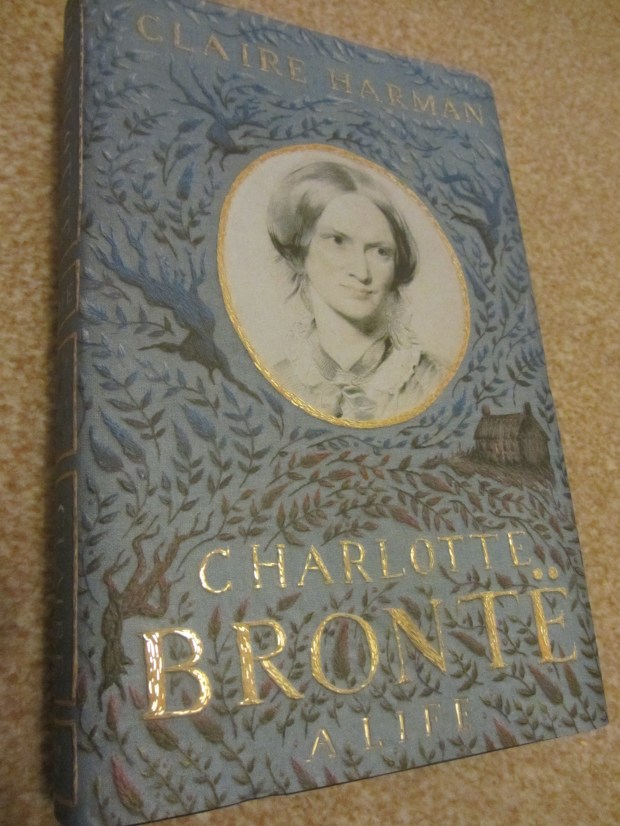

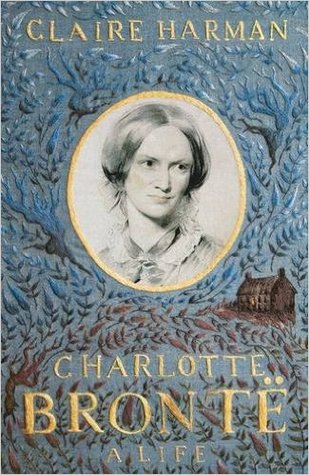

If I could recommend just one book from the recent flurry of Brontëana, it would be Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman, which I reviewed for For Books’ Sake back in November.

If I could recommend just one book from the recent flurry of Brontëana, it would be Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman, which I reviewed for For Books’ Sake back in November.

One of the things Harman’s wonderful biography does best is to trace how the Brontës’ childhood experiences found later expression in their fiction. A chapter on the publication of Jane Eyre (1847) is a highlight. Diehard fans might not encounter lots of new material, but Harman does make a revelation concerning Charlotte’s cause of death – not TB, as previously believed, but hyperemesis gravidarum, or extreme morning sickness. This will help you appreciate afresh the work of a “poet of suffering” whose novels were “all the more subversive because of [their] surface conventionality.” Interesting piece of trivia for you: this and the Janzing novel (above) open with the same scene from Charlotte’s time in Belgium.

Have you read any of these, or other recent Brontë-themed books? What were your thoughts?

Books as Objects of Beauty

At least half of my reading nowadays is e-books, usually downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss and read on my Kindle. All the same, I still love the feel and smell of paper books, and it’s a special treat when the books are things of beauty in their own right. A few books I’ve reviewed recently have been absolutely stunning physical objects. Here are some photographs and a rundown of their key attributes:

The Water Book by Alok Jha – Just look at that gorgeous, shiny cover! I was less taken with the contents of the book itself, but never mind. (My review is forthcoming at Nudge.)

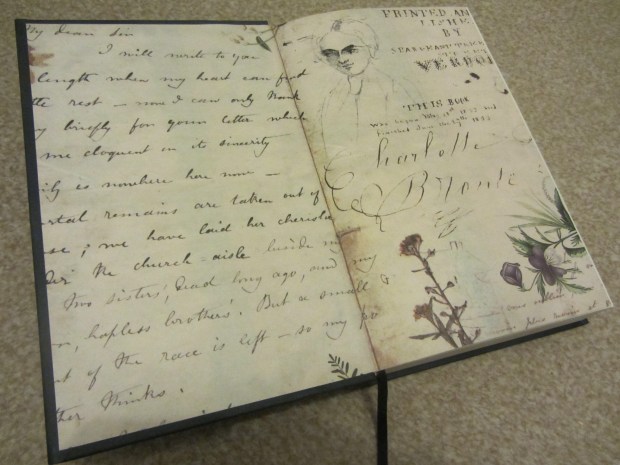

Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman – Embossed embroidery effect on the cover, handwriting and sketches (including the only known C. Brontë self-portrait, only recently identified) on the endpapers, and built-in ribbon bookmark. (My review will go up at For Books’ Sake on Wednesday.)

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James – The dustjacket of this Booker Prize winner is lovely enough, but take it off and you still hold a striking object, in appropriately Rastafarian colors. (Full review in December issue of Third Way magazine.)

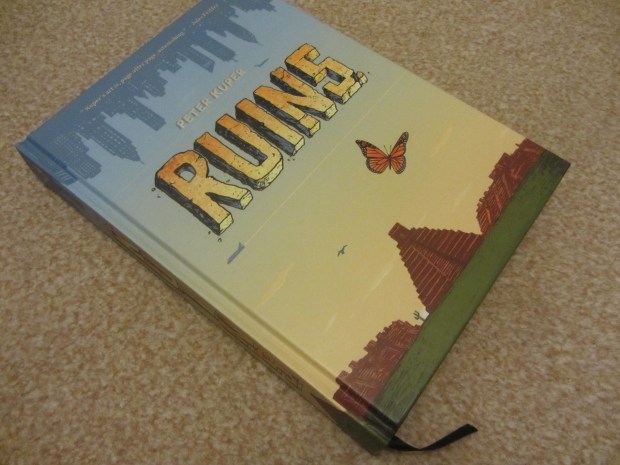

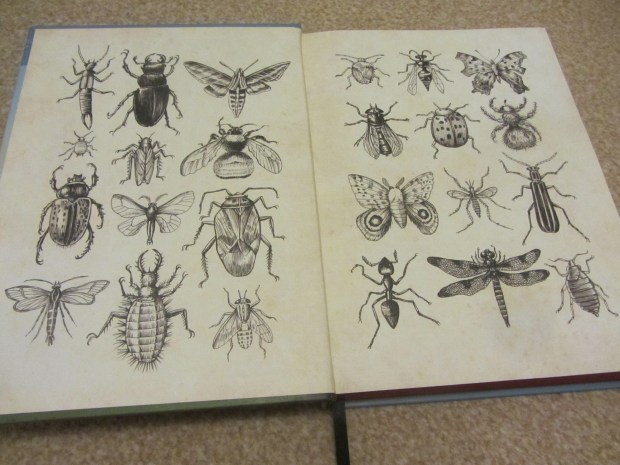

Ruins by Peter Kuper – Embossed title on the cover, with the monarch in matte; entomological drawings on the endpapers; alternating monochrome and full-color sequences; plus a built-in ribbon bookmark. (To be reviewed here in the near future.)

To survive in this modern age, physical books have to be more than just words on a page, because e-books do that much more efficiently. They simply have to be beautiful.

What are some of the most eye-catching books you’ve encountered recently?

Two Trips to the Theatre

Jane Eyre at the National Theatre

On October 3rd I was lucky enough to see a new production of Jane Eyre at London’s National Theatre. Thanks to theatre vouchers I had lying around, I paid all of £8 for my back-row seat, from which I had an excellent view, especially thanks to the pair of mini binoculars. Ten actors and musicians share all the roles. Sometimes a change of dress or hat is all that makes the distinction. For instance, the same actress (Laura Elphinstone) plays Helen Burns, Grace Poole, Adèle Varens, and St. John Rivers. One actor even plays Pilot the dog. His persistent “whoo-whoo” bark and habit of flopping at people’s feet make for charming comedy.

But the play belongs, of course, to Jane, and Madeleine Worrall is perfectly cast: unassuming yet passionate, a little firebrand. I can’t say for certain, but my impression is that she never leaves the stage during the entire production. She plays Jane at all ages: she voices a creepy baby cry when the bundle of cloth representing her infant self appears; other actors help her in and out of various dresses over a simple white shift as she grows up. The addition of a corset and petticoat indicates that she is now an adult, and a wedding dress and veil are the symbols of true love dangled before her eyes and then snatched away.

Set, props and music are all used to great effect. The action takes place on a complex of boardwalks, staircases and ladders, and most of the props are also wood and metal: stools, crates and window frames moved around to model different settings. The multiple levels allow for comings and goings but also for subtle displays of power relations. Objects hanging from the ceiling help to create location – family portraits and ominous red lighting signify Gateshead (the Reed house), simple sacking garments characterize Lowood School, and window frames and bare bulbs that flicker to Bertha’s laughs quite effectively evoke Thornfield Hall.

There is live musical backing at many points, with a piano, guitar, double bass and drums tucked off center under one of the boardwalks. The music ranges from instrumentals that wouldn’t be out of place in Downton Abbey or The Lord of the Rings to pop songs. An opera singer in a red satin dress wanders around singing snatches of folk spirituals and contemporary numbers. I certainly didn’t expect to hear Cee Lo Green’s “Crazy” during an adaptation of a nineteenth-century novel, but somehow it fits brilliantly.

The play is admirably true to the book. The two climactic fire scenes work very well, better than one might expect, and the romantic moments between Jane and Rochester are touchingly believable. I especially liked how journeys are suggested: a huddle of actors stand in the center of the stage and run in place to a percussion backing and a chant of destinations. One coach journey is even interrupted by a ‘piddle break’! Deaths are marked by opening a trap door near the edge of the stage and a character slowly descending some stairs out of sight.

The play started life in Bristol as a two-part adaptation stretching to four hours; for its move to London it has been condensed to just over three hours, but this still feels long, especially towards the end of the first act or in the aftermath of the revelation about Bertha. The St. John material, especially, drags – though that is true of the book as well. My main criticism of the production would be the way it sometimes tries to externalize Jane’s thoughts by having her ‘talk to herself’ via three or four other actors arguing. An angsty monologue à la Hamlet would have done the job just fine. Revealing Jane’s feelings for Rochester through a performance of the song “Mad About the Boy” likewise struck me as unsubtle.

![Painted by Evert A. Duyckinck, based on a drawing by George Richmond [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons/](https://bookishbeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/charlotte_bronte_coloured_drawing.png?w=620)

Charlotte Brontë. Painted by Evert A. Duyckinck, based on a drawing by George Richmond [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

A big anniversary is coming up: 2016 is the bicentennial of Charlotte Brontë’s birth. I’ve noticed a cluster of books being published or reissued in advance of her 200th birthday, such as Claire Harman’s biography, which I’ll review for For Books’ Sake, and a novel translated from the Dutch about Emily and Charlotte’s time in Belgium, Charlotte Brontë’s Secret Love by Jolien Janzing, which I’ll read for The Bookbag. There could be no better time for going back to her timeless stories, whether through the books themselves or another artistic expression.

To compare the thoughts of some professional theatregoers and see a few photos, check out the reviews on the Guardian and Telegraph websites.

When We Are Married by the Twyford & Ruscombe Players

J.B Priestley (1894–1984) is not a very familiar name for me, but my husband assures me he’s well known and loved here in England, if only for the play An Inspector Calls, which he studied at GCSE (it’s still a set text) and saw on stage. When We Are Married, one of the prolific Yorkshire author’s many plays, was first performed in 1938, though it’s set in 1908. I went to see it in our local village hall this past Saturday night.

The premise is simple: three couples (the Helliwells, Parkers and Soppitts) are celebrating their silver wedding anniversary, having all been married in the same chapel on the same morning. They even have a photo commemorating the occasion, and today they hope to recreate that shot. Over the years they have done well for themselves: one man is an alderman and another a counsellor; all three are heavily involved in their local chapel.

Press photograph of the original 1938 production: (clockwise from top left) Raymond Huntley, Lloyd Pearson, Ernest Butcher, Ethel Coleridge, Muriel George, and Helena Pickard. (From “The World of the Theatre,” Illustrated London News, 5 November 1938.)

All is not well in this small Yorkshire village, however. They are disappointed with their newly hired organist, a la-di-da southerner named Gerald Forbes who has been seen stepping out with young ladies at night. The whole play takes place in the drawing room of Alderman Helliwell’s home, and in an early scene the three gentlemen summon Gerald with the intention of dismissing him. However, he has his own surprise: a letter from the parish’s former parson, confessing that he wasn’t properly licensed to perform wedding ceremonies at the time. Consequently, these three pillars of the community are not legally married after all.

The news soon gets out thanks to a sullen cook who was listening behind the door and broadcasts the story at the local pub. In Act II the couples – including Gerald and his secret sweetheart, the Helliwells’ niece – take it in turns to come on stage for private chats. They spend time imagining what could be different in their lives if they really were single. Henpecked Herbert Soppitt gets his own back after years of cowering, while Mrs. Parker finally tells the Counsellor how dull and stingy she’s always found him to be.

The two best characters are Ruby Birtle, the Helliwells’ garrulous maid, and Henry Ormonroyd, a drunken photographer sent by the Yorkshire Argus. He functions like the Fool in this Shakespearean comedy of reversals, and happens to have some of the most profound lines. Will these unlucky couples get their anniversary photograph after all?

This was an enjoyable local production. The simple set was easy to maintain, and the acting – especially the Yorkshire accents – unimpeachable. The audience was in three sections in a rough semicircle around the action; my chair was just five feet behind a chaise longue on set. My only criticism would be that one of the three wives looked 20 years younger than the rest. I’ll certainly venture out for another show by the Twyford & Ruscombe Players.

Literary Tourism in Manchester

Over the August bank holiday weekend, my husband and I went to Manchester for the first time. Big cities aren’t our usual vacation destinations of choice, but we were going for the Sufjan Stevens gig at the O2 Apollo on the 31st and wanted to do the city justice while we were there, so stayed two nights at a chain hotel and worked out everything we wanted to see and do there, including two literary pilgrimages for me: Elizabeth Gaskell’s House and Chetham’s Library, where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels met and discussed ideas in the summer of 1845. Armed only with a two-page map sliced out of an eleven-year-old Rough Guide, we felt perhaps a little ill-equipped, but managed to have a nice time nonetheless.

In preparation, I read The Communist Manifesto on the train ride north. It’s only 50 pages, and even with an introduction and multiple prefaces my Vintage Classics copy only comes to 70-some pages. That’s not to say it’s an easy read. I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the thread of the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. In fact, it had never occurred to me that this was first issued in Marx’s native German; like Darwin’s Origin of Species, another seminal Victorian text, it has so many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors that have entered into common discourse that I simply assumed it was composed in English.

After leaving our bags at the hotel on Sunday afternoon, we wandered over to the Gaskell House. It’s only open a few days a week, so we were lucky to be around during its opening hours. All of the house’s contents were sold at auction early in the twentieth century, so none of the furnishings are original, but the current contents have been painstakingly chosen to suggest what the house would have looked like at the time Gaskell and her family – a Unitarian minister husband and their four daughters – lived there. I especially enjoyed seeing William’s study and hearing how Charlotte Brontë hid behind the curtains in the drawing room so she wouldn’t have to socialize with the Gaskells’ visitors. The staff are knowledgeable and unfussy; unlike in your average National Trust house, they let you sit on the furniture and touch the objects. The gardens are also beautifully landscaped.

Talk about a contrast, though: look across the street and you see council housing and rubbish piled up on the pavement. In Gaskell’s time this was probably a genteel suburb, but now it’s an easy walk from the city center and in a considerably down-at-heel area. Indeed, we were taken aback by how grimy parts of Manchester were, and by how many homeless we encountered.

I’ve read four of Gaskell’s books: Mary Barton, North and South, Cranford and The Life of Charlotte Brontë. She’s not one of my favorite Victorian novelists, but I enjoyed each of those and intend to – someday – read Sylvia’s Lovers and Wives and Daughters, which was a few pages from completion when Gaskell died of a sudden heart attack in their second home in Hampshire, aged 55, in 1865.

Afterwards we stopped into the city’s Art Gallery and then headed to Mr Thomas’s Chop House for roast lamb and corned beef hash, then on to Sugar Junction to meet a blogger friend, the fabulous Lucy (aka Literary Relish), who I’d been corresponding with online for about two years but never met in real life. She graciously treated us to drinks and dessert at this cute café (one of the city’s many hip eateries) where she often hosts the Manchester Book Club, and we chatted about books and travel spots for a pleasant hour and a half.

On Monday we explored the Castlefield area with its canals and Roman ruins and went round both the Museum of Science and Industry and the People’s Museum, which together give a powerful sense of the city’s industrial and revolutionary past. We also toured the cathedral, took a peek at a Special Collections exhibit on the Gothic plus the main reading room at John Rylands Library, and browsed the huge selection at the main Waterstones branch. (On a future visit we are reliably informed that we must go find Sharston Books, a warehouse-scale secondhand shop out of town.) After a necessary pit stop for caffeine at The Foundation Coffee House and the best pizza we’ve ever had in the UK at Slice (including a Nutella and banana calzone for pudding), we headed over to the gig, which was terrific but not the purpose of this blog post.

Contrast between old and new Manchester: the hideous Beetham Tower on the left and Roman ruins in the foreground.

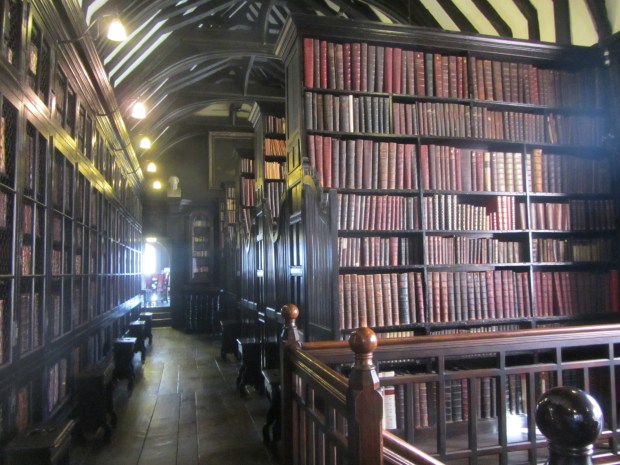

Our trip only spanned a Sunday and a bank holiday, so we missed seeing the inside of the hugely impressive Central Library and the 19th-century Portico Library. On Tuesday morning, though, we had just enough time before our train back to stop into Chetham’s Library. It’s a beautiful old library with rank after rank of leather-bound books sheltering amidst dark wood and mullioned windows. I love being in these kinds of places. They smell divine, and you can imagine holing up in a corner and reading all day, with the atmosphere beaming all kinds of lofty thoughts into your brain. We had the place to ourselves on this sunny morning and sat for a while in the bright alcove where Marx and Engels studied.

Apart from The Communist Manifesto, my reading on this trip was largely unrelated: My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff, a delightful literary memoir (review coming later this month); Number 11 by Jonathan Coe, a funny and mildly disturbing state-of-England and coming-of-age novel (releases November 11th); and The Mountain Can Wait by Sarah Leipciger, an atmospheric family novel set in the forests of Canada.

What have been some of your recent literary destinations? Do you like to read books related to the place you’re going, or do you choose your holiday reading at random?

After Me Comes the Flood was rejected by 14 publishers; even her viva examiners, who passed her without corrections, were “ungracious,” she remarked. What it comes down to, she thinks, is simply that no one liked the book or knew what to make of it. It seemed unmarketable because it didn’t fit into a particular genre. At this point I was sheepishly keeping my head down, glad that Perry couldn’t possibly know about my largely unfavorable review in Third Way magazine. I confess that my reaction was roughly similar to the general consensus: “Not quite an allegory, [the book] still suffers from that genre’s pitfalls, such as one-dimensional characters,” I wrote.

After Me Comes the Flood was rejected by 14 publishers; even her viva examiners, who passed her without corrections, were “ungracious,” she remarked. What it comes down to, she thinks, is simply that no one liked the book or knew what to make of it. It seemed unmarketable because it didn’t fit into a particular genre. At this point I was sheepishly keeping my head down, glad that Perry couldn’t possibly know about my largely unfavorable review in Third Way magazine. I confess that my reaction was roughly similar to the general consensus: “Not quite an allegory, [the book] still suffers from that genre’s pitfalls, such as one-dimensional characters,” I wrote. It will be interesting to see how she imagines a platonic friendship between the sexes in a historical setting, and the Dickensian and Gothic touches, even from the little taster I got, were delicious. I was especially intrigued to learn about her research into the friendship ‘triangle’ (betrayal! early death! forgiveness!) between William Ewart Gladstone, Alfred Tennyson, and Arthur Henry Hallam. Perry said she thinks the tide may be turning, that friendships rather than romantic love could be starting to dominate fiction; perhaps Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life from last year would be a good example.

It will be interesting to see how she imagines a platonic friendship between the sexes in a historical setting, and the Dickensian and Gothic touches, even from the little taster I got, were delicious. I was especially intrigued to learn about her research into the friendship ‘triangle’ (betrayal! early death! forgiveness!) between William Ewart Gladstone, Alfred Tennyson, and Arthur Henry Hallam. Perry said she thinks the tide may be turning, that friendships rather than romantic love could be starting to dominate fiction; perhaps Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life from last year would be a good example. In the other sessions I attended, a group of clergy revealed the shortlist for the £10,000

In the other sessions I attended, a group of clergy revealed the shortlist for the £10,000  Chaired by contemporary Anglican novelist

Chaired by contemporary Anglican novelist

The Tsar of Love and Techno

The Tsar of Love and Techno

Mad Feast

Mad Feast

Addiction Is Addiction

Addiction Is Addiction The Gratitude Diaries by Janice Kaplan: We can all do with a little encouragement to appreciate what we already have. In so many areas of life – finances, career, relationship, even the weather – we’re all too often hoping for more or better than what we are currently experiencing. Here Kaplan undertakes a year-long experiment to see if gratitude can improve every aspect of her life. She draws her information from interviews with researchers and celebrities, quotes from philosophers, and anecdotes from her own and friends’ lives. It’s easy, pleasant reading I’d recommend to fans of Gretchen Rubin.

The Gratitude Diaries by Janice Kaplan: We can all do with a little encouragement to appreciate what we already have. In so many areas of life – finances, career, relationship, even the weather – we’re all too often hoping for more or better than what we are currently experiencing. Here Kaplan undertakes a year-long experiment to see if gratitude can improve every aspect of her life. She draws her information from interviews with researchers and celebrities, quotes from philosophers, and anecdotes from her own and friends’ lives. It’s easy, pleasant reading I’d recommend to fans of Gretchen Rubin. The Water Book by Alok Jha: An interdisciplinary look at water’s remarkable properties and necessity for life on earth. For the most part, Jha pitches his work at an appropriate level. However, if it’s been a while since you studied chemistry at school, you may struggle. Part IV, on the search for water in space, is too in-depth for popular science and tediously long. In December 2013 Jha was part of a month-long Antarctic expedition. He uses the trip as an effective framing device, but I would have liked more memoiristic passages. All in all, I was hoping for less hard science and more reflection on water’s importance to human culture.

The Water Book by Alok Jha: An interdisciplinary look at water’s remarkable properties and necessity for life on earth. For the most part, Jha pitches his work at an appropriate level. However, if it’s been a while since you studied chemistry at school, you may struggle. Part IV, on the search for water in space, is too in-depth for popular science and tediously long. In December 2013 Jha was part of a month-long Antarctic expedition. He uses the trip as an effective framing device, but I would have liked more memoiristic passages. All in all, I was hoping for less hard science and more reflection on water’s importance to human culture. Claxton: Field Notes from a Small Planet by Mark Cocker: Mark Cocker is the Guardian’s country diarist for Norfolk. The short pieces in this book are reprints of his columns, some expanded or revised. I would advise keeping this as a bedside or coffee table book from which you read no more than one or two entries a week, so that you always stay in chronological sync. You’ll appreciate the book most if you experience nature along with Cocker, rather than reading from front cover to back in a few sittings. The problem with the latter approach is that there is inevitable repetition of topics across years. All told, after spending a vicarious year in Claxton, you’ll agree: “How miraculous that we are all here, now, in this one small place.”

Claxton: Field Notes from a Small Planet by Mark Cocker: Mark Cocker is the Guardian’s country diarist for Norfolk. The short pieces in this book are reprints of his columns, some expanded or revised. I would advise keeping this as a bedside or coffee table book from which you read no more than one or two entries a week, so that you always stay in chronological sync. You’ll appreciate the book most if you experience nature along with Cocker, rather than reading from front cover to back in a few sittings. The problem with the latter approach is that there is inevitable repetition of topics across years. All told, after spending a vicarious year in Claxton, you’ll agree: “How miraculous that we are all here, now, in this one small place.” A Mile Down by David Vann: Vann, better known for fiction, tells the real-life story of his ill-fated journeys at sea. He hired a Turkish crew to build him a boat of his own, and before long shoddy workmanship, language difficulties, bureaucracy, and debts started to make it all seem like a very bad idea. Was he cursed? Would he follow his father into suicide? The day-to-day details of boat-building and sailing can be tedious, and there’s an angry tone that’s unpleasant; Vann seems to think everybody else was incompetent or a crook. However, he does an incredible job of narrating two climactic storms he sailed through.

A Mile Down by David Vann: Vann, better known for fiction, tells the real-life story of his ill-fated journeys at sea. He hired a Turkish crew to build him a boat of his own, and before long shoddy workmanship, language difficulties, bureaucracy, and debts started to make it all seem like a very bad idea. Was he cursed? Would he follow his father into suicide? The day-to-day details of boat-building and sailing can be tedious, and there’s an angry tone that’s unpleasant; Vann seems to think everybody else was incompetent or a crook. However, he does an incredible job of narrating two climactic storms he sailed through.

Running on the March Wind by Lenore Keeshig: Keeshig is a First Nations Canadian; these poems are full of images of Nanabush the Trickster, language from legal Indian acts, and sly subversion of stereotypes – cowboys and Indians, the only good Indian is a dead Indian (in “Making New”), the white man’s burden, and so on. In places I found these more repetitive and polemical than musical, though I did especially like the series of poems on trees.

Running on the March Wind by Lenore Keeshig: Keeshig is a First Nations Canadian; these poems are full of images of Nanabush the Trickster, language from legal Indian acts, and sly subversion of stereotypes – cowboys and Indians, the only good Indian is a dead Indian (in “Making New”), the white man’s burden, and so on. In places I found these more repetitive and polemical than musical, though I did especially like the series of poems on trees. Very British Problems Abroad

Very British Problems Abroad Purity

Purity A Brief History of Seven Killings

A Brief History of Seven Killings Kitchens of the Great Midwest

Kitchens of the Great Midwest The Japanese Lover

The Japanese Lover Accidental Saints: Finding God in All the Wrong People

Accidental Saints: Finding God in All the Wrong People The Road to Little Dribbling: Adventures of an American in Britain by Bill Bryson: Bryson’s funniest book for many years. It meant a lot to me since I am also an American expat in England. Two points of criticism, though: although he moves roughly from southeast to northwest in the country, the stops he makes are pretty arbitrary, and his subjects of mockery are often what you’d call easy targets. Do we really need Bryson’s lead to scorn litterbugs and reality television celebrities? Still, I released many an audible snort of laughter while reading.

The Road to Little Dribbling: Adventures of an American in Britain by Bill Bryson: Bryson’s funniest book for many years. It meant a lot to me since I am also an American expat in England. Two points of criticism, though: although he moves roughly from southeast to northwest in the country, the stops he makes are pretty arbitrary, and his subjects of mockery are often what you’d call easy targets. Do we really need Bryson’s lead to scorn litterbugs and reality television celebrities? Still, I released many an audible snort of laughter while reading. Shaler’s Fish

Shaler’s Fish

Landfalls

Landfalls Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill: Not as innovative or profound as I was expecting given the rapturous reviews from so many quarters. It’s an attempt to tell an old, old story in a new way: wife finds out her husband is cheating. Offill’s style is fragmentary and aphoristic. Some of the facts and sayings are interesting, but most just sit there on the page and don’t add to the story. What I did find worthwhile was tracing the several tense and pronoun changes: from first-person, past tense into present tense, then to third-person and back to first-person for the final page.

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill: Not as innovative or profound as I was expecting given the rapturous reviews from so many quarters. It’s an attempt to tell an old, old story in a new way: wife finds out her husband is cheating. Offill’s style is fragmentary and aphoristic. Some of the facts and sayings are interesting, but most just sit there on the page and don’t add to the story. What I did find worthwhile was tracing the several tense and pronoun changes: from first-person, past tense into present tense, then to third-person and back to first-person for the final page. As Far As I Know by Roger McGough: A bit silly for my tastes; lots of puns and other plays on words. In style they feel like children’s poems, but with vocabulary and themes more suited to adults. I did like “Indefinite Definitions,” especially BRUPT: “A brupt is a person, curt and impolite / Brusque and impatient / Who thinks he’s always right.” The whole series is like that: words with the indefinite article cut off and an explanation playing on the original word’s connotations. From the “And So to Bed” concluding cycle, I loved Camp bed: “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu / on the bedside table / Gardenia on the pillow / Silk pyjamas neatly folded.”

As Far As I Know by Roger McGough: A bit silly for my tastes; lots of puns and other plays on words. In style they feel like children’s poems, but with vocabulary and themes more suited to adults. I did like “Indefinite Definitions,” especially BRUPT: “A brupt is a person, curt and impolite / Brusque and impatient / Who thinks he’s always right.” The whole series is like that: words with the indefinite article cut off and an explanation playing on the original word’s connotations. From the “And So to Bed” concluding cycle, I loved Camp bed: “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu / on the bedside table / Gardenia on the pillow / Silk pyjamas neatly folded.” The Penguin Lessons: What I Learned from a Remarkable Bird

The Penguin Lessons: What I Learned from a Remarkable Bird