Some Books I Was Surprised to Love

Like most fiction readers, I generally stick with what I’m pretty sure I’ll like. For me that means that, unless I’ve heard very good feedback that makes me think the book will stand out from its peers, I tend to avoid science fiction, fantasy, and mystery novels (or genre fiction in general). I’m also leery of magic realism and allegories, as these techniques can so often be cringe-inducing. But occasionally a book will come along that proves me wrong.

For instance, last week I finished To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis. Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!). Once I got into it, I read it extremely quickly – finishing the final 230 pages on one Sunday afternoon and evening – and it provoked a continuous stream of snorts. I can hardly think of anyone I wouldn’t recommend it to.

For instance, last week I finished To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis. Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!). Once I got into it, I read it extremely quickly – finishing the final 230 pages on one Sunday afternoon and evening – and it provoked a continuous stream of snorts. I can hardly think of anyone I wouldn’t recommend it to.

This got me thinking about some other pleasantly surprising books that took me outside of my usual reading comfort zone in recent years:

Dark Eden by Chris Beckett: Six generations ago a pair of astronauts landed on the planet Eden and became matriarch and patriarch of a new race of eerily primitive humans. A young leader, John Redlantern, rises up within the group, determined to free his people from their limited worldview by demythologizing their foundational story. Through events that mirror many of the accounts in Genesis and Exodus, Beckett provides an intriguing counterpoint to the ways Jews and Christians relate to the biblical narrative. Page-turning science fiction with deep theological implications. I liked each of the two sequels less than the book that went before, but they’re still worth reading.

Dark Eden by Chris Beckett: Six generations ago a pair of astronauts landed on the planet Eden and became matriarch and patriarch of a new race of eerily primitive humans. A young leader, John Redlantern, rises up within the group, determined to free his people from their limited worldview by demythologizing their foundational story. Through events that mirror many of the accounts in Genesis and Exodus, Beckett provides an intriguing counterpoint to the ways Jews and Christians relate to the biblical narrative. Page-turning science fiction with deep theological implications. I liked each of the two sequels less than the book that went before, but they’re still worth reading.

The Flavia de Luce mysteries by Alan Bradley: Normally I shy away from series and tire of child narrators – and yet I find the Flavia de Luce novels positively delightful. Why? Well, Canadian author Alan Bradley’s quaintly authentic mysteries are set at Buckshaw, a crumbling country manor house in 1950s England, where the titular eleven-year-old heroine, also the narrator, performs madcap chemistry experiments and solves small-town murders. The Dead in Their Vaulted Arches (#6) is the best yet. In this installment, Flavia finally learns of her unexpected inheritance from her mother. The most recent, Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d (#8), is a close second.

The Flavia de Luce mysteries by Alan Bradley: Normally I shy away from series and tire of child narrators – and yet I find the Flavia de Luce novels positively delightful. Why? Well, Canadian author Alan Bradley’s quaintly authentic mysteries are set at Buckshaw, a crumbling country manor house in 1950s England, where the titular eleven-year-old heroine, also the narrator, performs madcap chemistry experiments and solves small-town murders. The Dead in Their Vaulted Arches (#6) is the best yet. In this installment, Flavia finally learns of her unexpected inheritance from her mother. The most recent, Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d (#8), is a close second.

A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness: The thinking gal’s Twilight. Harkness, a historian of science, draws on her knowledge of everything from medieval alchemy to recent DNA mapping. The main character, reluctant witch Diana Bishop, is studying alchemical treatises at the Bodleian Library. She calls up an enchanted manuscript from Ashmole’s original collection, presumed missing since 1859. There are three excised pages, and the book instantly draws attention from the myriad “creatures” (non-humans) plaguing Oxford. Enter Matthew Clairmont, a mega-hot vampire with a conscience. From rural France to upstate New York, he and Diana fight off rival vampires and the witches who killed Diana’s parents. As with Beckett’s books, the two sequels are a bit of a letdown, but the first book is great fun.

A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness: The thinking gal’s Twilight. Harkness, a historian of science, draws on her knowledge of everything from medieval alchemy to recent DNA mapping. The main character, reluctant witch Diana Bishop, is studying alchemical treatises at the Bodleian Library. She calls up an enchanted manuscript from Ashmole’s original collection, presumed missing since 1859. There are three excised pages, and the book instantly draws attention from the myriad “creatures” (non-humans) plaguing Oxford. Enter Matthew Clairmont, a mega-hot vampire with a conscience. From rural France to upstate New York, he and Diana fight off rival vampires and the witches who killed Diana’s parents. As with Beckett’s books, the two sequels are a bit of a letdown, but the first book is great fun.

You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine by Alexandra Kleeman: A full-on postmodern satire bursting with biting commentary on body image, consumerism and conformity. The narrator, known only as A, lives in a shared suburban apartment. She and her roommate, B, are physically similar and emotionally dependent, egging each other on to paranoid anorexia. Television and shopping are the twin symbolic pillars of a book about the commodification of the body. In a culture of self-alienation where we compulsively buy things we don’t need, have no idea where our food comes from and worry about keeping up a facade of normalcy, Kleeman’s is a fresh voice advocating the true sanity of individuality.

You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine by Alexandra Kleeman: A full-on postmodern satire bursting with biting commentary on body image, consumerism and conformity. The narrator, known only as A, lives in a shared suburban apartment. She and her roommate, B, are physically similar and emotionally dependent, egging each other on to paranoid anorexia. Television and shopping are the twin symbolic pillars of a book about the commodification of the body. In a culture of self-alienation where we compulsively buy things we don’t need, have no idea where our food comes from and worry about keeping up a facade of normalcy, Kleeman’s is a fresh voice advocating the true sanity of individuality.

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North: The theme of a character reliving the same life over and over will no doubt have you thinking of Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life, but I liked this book so much better. Perhaps simply because of the first-person narration, I developed much more of a fondness for Harry August and his multiple life stories than I ever did for Ursula Todd. Harry, the illegitimate son of a servant girl, is born in the same manner each time – on New Year’s Day 1919, in the ladies’ restroom at Berwick-upon-Tweed rail station! – but becomes many people in his different lives.

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North: The theme of a character reliving the same life over and over will no doubt have you thinking of Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life, but I liked this book so much better. Perhaps simply because of the first-person narration, I developed much more of a fondness for Harry August and his multiple life stories than I ever did for Ursula Todd. Harry, the illegitimate son of a servant girl, is born in the same manner each time – on New Year’s Day 1919, in the ladies’ restroom at Berwick-upon-Tweed rail station! – but becomes many people in his different lives.

What books were you surprised to love recently?

Starting the Year as I Mean to Go On?

The houseguests have gone home, the Christmas tree is coming down tomorrow, and it’s darned cold. I’m feeling stuck in a rut in my career, the blog, and so many other areas of life. It’s hard not to think of 2017 as a huge stretch of emptiness with very few bright spots. All I want to do is sit around in my new fuzzy bathrobe and read under the cat. Luckily, I’ve had some great books to accompany me through the Christmas period and have finished five so far this year.

I thought I’d continue the habit of writing two-sentence reviews (or maybe no more than three), except when I’m writing proper full-length reviews on assignment or for blog tours or other websites. Granted, they’re usually long and multi-part sentences, and this isn’t actually a time-saving trick – as Blaise Pascal once said, “I’m sorry I wrote you such a long letter; I didn’t have time to write a short one” – but it feels like good discipline.

So here’s some mini-reviews of what I’ve been reading in late December and early January:

The Dark Flood Rises, Margaret Drabble

The “dark flood” is D.H. Lawrence’s metaphor for death, and here it corresponds to busy seventy-something Fran’s obsession with last words, obituaries and the search for the good death as many of her friends and acquaintances succumb – but also to literal flooding in the west of England and (dubious, this) to mass immigration of Asians and Africans into Europe. This is my favorite of the five Drabble books that I’ve read – it’s closest in style and tone to her sister A.S. Byatt as well as to Tessa Hadley, and the themes of old age and life’s randomness are strong – even though there seem to be too many characters and the Canary Islands subplot mostly feels like an unnecessary distraction. (Public library)

The “dark flood” is D.H. Lawrence’s metaphor for death, and here it corresponds to busy seventy-something Fran’s obsession with last words, obituaries and the search for the good death as many of her friends and acquaintances succumb – but also to literal flooding in the west of England and (dubious, this) to mass immigration of Asians and Africans into Europe. This is my favorite of the five Drabble books that I’ve read – it’s closest in style and tone to her sister A.S. Byatt as well as to Tessa Hadley, and the themes of old age and life’s randomness are strong – even though there seem to be too many characters and the Canary Islands subplot mostly feels like an unnecessary distraction. (Public library)

Hogfather, Terry Pratchett

In Discworld belief causes imagined beings to exist, so when a devious plot to control children’s minds results in a dearth of belief in the Hogfather, the Fat Man temporarily disappears and Death has to fill in for him on this Hogswatch night. I laughed aloud a few times while reading this clever Christmas parody, but I had a bit of trouble following the plot and grasping who all the characters were given that this was my first Discworld book; in general I’d say that Pratchett is another example of British humor that I don’t entirely appreciate (along with Monty Python and Douglas Adams) – he’s my husband’s favorite, but I doubt I’ll try another of his books. (Own copy)

In Discworld belief causes imagined beings to exist, so when a devious plot to control children’s minds results in a dearth of belief in the Hogfather, the Fat Man temporarily disappears and Death has to fill in for him on this Hogswatch night. I laughed aloud a few times while reading this clever Christmas parody, but I had a bit of trouble following the plot and grasping who all the characters were given that this was my first Discworld book; in general I’d say that Pratchett is another example of British humor that I don’t entirely appreciate (along with Monty Python and Douglas Adams) – he’s my husband’s favorite, but I doubt I’ll try another of his books. (Own copy)

Love of Country: A Hebridean Journey, Madeleine Bunting

In a reprise of childhood holidays that inevitably headed northwest, Bunting takes a series of journeys around the Hebrides and weaves together her contemporary travels with the religion, folklore and history of this Scottish island chain, an often sad litany of the Gaels’ poverty and displacement that culminated with the brutal Clearances. Rather than giving an exhaustive survey, she chooses seven islands to focus on and tells stories of unexpected connections – Orwell’s stay on Jura, Lord Leverhulme’s (he of Port Sunlight and Unilever) purchase of Lewis, and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s landing on Eriskay – as she asks how geography influences history and what it truly means to belong to a place. (Public library)

In a reprise of childhood holidays that inevitably headed northwest, Bunting takes a series of journeys around the Hebrides and weaves together her contemporary travels with the religion, folklore and history of this Scottish island chain, an often sad litany of the Gaels’ poverty and displacement that culminated with the brutal Clearances. Rather than giving an exhaustive survey, she chooses seven islands to focus on and tells stories of unexpected connections – Orwell’s stay on Jura, Lord Leverhulme’s (he of Port Sunlight and Unilever) purchase of Lewis, and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s landing on Eriskay – as she asks how geography influences history and what it truly means to belong to a place. (Public library)

Cobwebs and Cream Teas: A Year in the Life of a National Trust House, Mary Mackie

Mackie’s husband was Houseman and then Administrator at Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk in the 1980s – live-in roles that demanded a wide range of skills and much more commitment than the usual 9 to 5 (when he borrowed a pedometer he learned that he walked 15 miles in the average day, without leaving the house!). Her memoir of their first year at Felbrigg proceeds chronologically, from the intense cleaning and renovations of the winter closed season through to the following Christmas’ festivities, and takes in along the way plenty of mishaps and visitor oddities. It will delight anyone who’d like a behind-the-scenes look at the life of a historic home. (Own copy)

Mackie’s husband was Houseman and then Administrator at Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk in the 1980s – live-in roles that demanded a wide range of skills and much more commitment than the usual 9 to 5 (when he borrowed a pedometer he learned that he walked 15 miles in the average day, without leaving the house!). Her memoir of their first year at Felbrigg proceeds chronologically, from the intense cleaning and renovations of the winter closed season through to the following Christmas’ festivities, and takes in along the way plenty of mishaps and visitor oddities. It will delight anyone who’d like a behind-the-scenes look at the life of a historic home. (Own copy)

The Bridge Ladies: A Memoir, Betsy Lerner

When life unexpectedly took the middle-aged Lerner back to her hometown of New Haven, Connecticut, she spent several years sitting in on her mother’s weekly bridge games to learn more about these five Jewish octogenarians who have been friends for 50 years and despite their old-fashioned reserve have seen each other through the loss of careers, health, husbands and children. Although Lerner also took bridge lessons herself, this is less about the game and more about her ever-testy relationship with her mother (starting with her rebellious teenage years), the ageing process, and the ways that women of different generations relate to their family and friends. It wouldn’t be exaggerating to say that every mother and daughter should read this; I plan to shove it in my mother’s and sister’s hands the next time I’m in the States. (Own copy)

When life unexpectedly took the middle-aged Lerner back to her hometown of New Haven, Connecticut, she spent several years sitting in on her mother’s weekly bridge games to learn more about these five Jewish octogenarians who have been friends for 50 years and despite their old-fashioned reserve have seen each other through the loss of careers, health, husbands and children. Although Lerner also took bridge lessons herself, this is less about the game and more about her ever-testy relationship with her mother (starting with her rebellious teenage years), the ageing process, and the ways that women of different generations relate to their family and friends. It wouldn’t be exaggerating to say that every mother and daughter should read this; I plan to shove it in my mother’s and sister’s hands the next time I’m in the States. (Own copy) ![]()

Waiting on the Word, Malcolm Guite

Guite chooses well-known poems (by Christina Rossetti, John Donne, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge et al.) as well as more obscure contemporary ones as daily devotional reading between the start of Advent and Epiphany; I especially liked his sonnet sequence in response to the seven “O Antiphons.” His commentary is learned and insightful, and even if at times I thought he goes into too much in-depth analysis rather than letting the poems speak for themselves, this remains a very good companion to the Christmas season for any poetry lover. (E-book from NetGalley)

Guite chooses well-known poems (by Christina Rossetti, John Donne, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge et al.) as well as more obscure contemporary ones as daily devotional reading between the start of Advent and Epiphany; I especially liked his sonnet sequence in response to the seven “O Antiphons.” His commentary is learned and insightful, and even if at times I thought he goes into too much in-depth analysis rather than letting the poems speak for themselves, this remains a very good companion to the Christmas season for any poetry lover. (E-book from NetGalley)

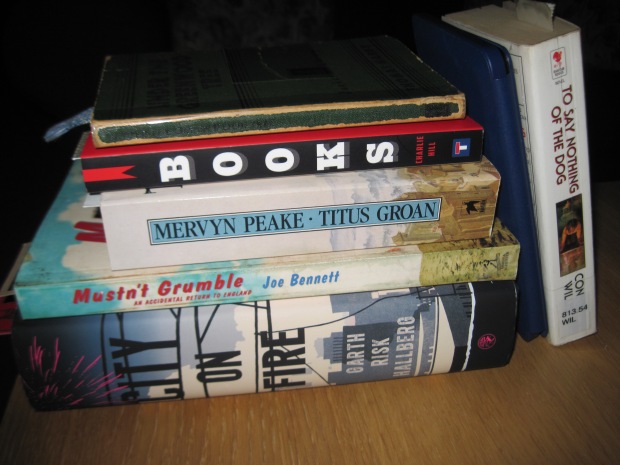

I started too many books over Christmas and have sort of put six of them on hold – including Titus Groan, which I’m thinking of quitting (it takes over 50 pages for one servant to tell another that the master has had a son?!), and City on Fire, which is wonderful but dispiritingly long: even after two good sessions with it in the days after Christmas, I’ve barely made a dent.

I started too many books over Christmas and have sort of put six of them on hold – including Titus Groan, which I’m thinking of quitting (it takes over 50 pages for one servant to tell another that the master has had a son?!), and City on Fire, which is wonderful but dispiritingly long: even after two good sessions with it in the days after Christmas, I’ve barely made a dent.

Stack on left = on hold (the book on top is Under the Greenwood Tree); standing up at right = books I’m actually reading.

However, the three books that I am actively reading I’m loving: To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis is an uproarious blend of time travel science fiction and Victorian pastiche (university library), Pachinko by Min Jin Lee is a compulsive historical saga set in Korea (ARC from NetGalley), and the memoir Birds Art Life by Kyo Maclear has been compared to H Is for Hawk in the way she turns to birdwatching to deal with depression (e-book from Edelweiss). I also will be unlikely to resist my e-galley of the latest Anne Lamott book, Hallelujah Anyway (forthcoming in April, ARC from Edelweiss), for much longer.

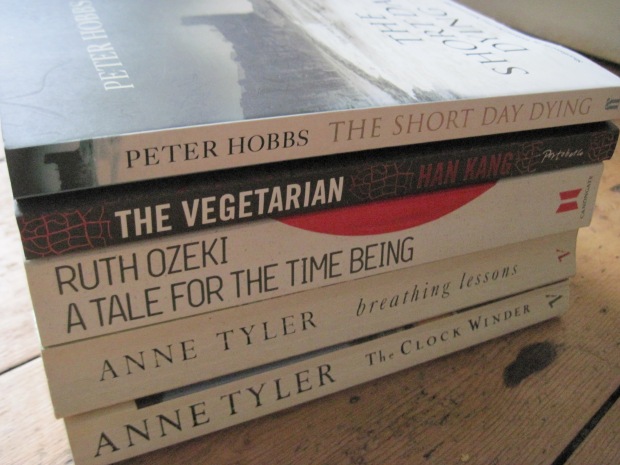

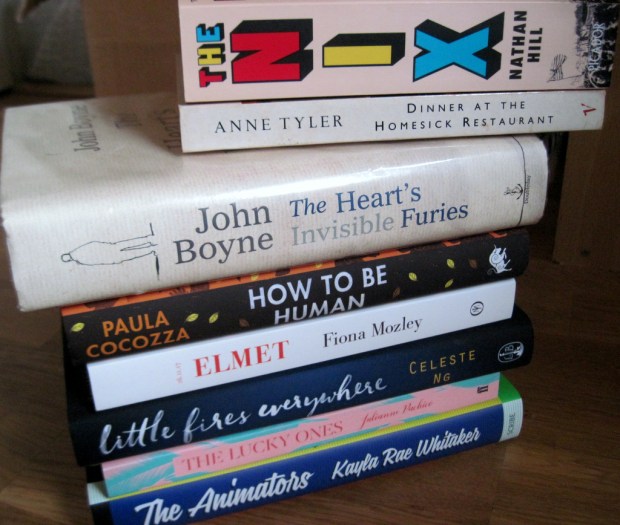

Meanwhile, in post-holiday charity shopping I scored six books for £1.90: one’s been tucked away as a present for later in the year; the Ozeki I’ve already read, but it’s a favorite so I’m glad to own it; and the rest are new to me. I look forward to trying Han Kang; Anne Tyler is a reliable choice for a cozy read; and the Hobbs sounds like a wonderful Victorian-set novel.

All in all, I seem to be starting my year in books as I mean to go on: reading a ton; making sure I review most or all of the books, even if I write just a few sentences; maintaining a balance between my own books, library books, and recent or advance NetGalley/Edelweiss reads; and failing to restrain myself from buying more.

Now if I could just work on my general attitude…

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.  The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

Anything by Bill Bryson

Anything by Bill Bryson

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!).

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!). Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room. Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This isn’t a happy family story. It’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate. Yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right, and it’s pulsing with emotion. One theme is how there can be different interpretations of the same events even within a small family. The novel is particularly strong on atmosphere, reminding me of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea and Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. Fuller also manages her complex structure very well.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This isn’t a happy family story. It’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate. Yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right, and it’s pulsing with emotion. One theme is how there can be different interpretations of the same events even within a small family. The novel is particularly strong on atmosphere, reminding me of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea and Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. Fuller also manages her complex structure very well.