Six Degrees of Separation: From Ruth Ozeki to Ruth Padel

This month we begin with The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, which recently won the Women’s Prize for Fiction. It happens to be my least favourite of her books that I’ve read so far, but I was pleased to see her work recognised nonetheless. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

#1 One of the peripheral characters in Ozeki’s novel is an Eastern European philosopher who goes by “The Bottleman.” I had to wonder if he was based on avant-garde Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Back in 2010, when I was working at a university library in London and had access to nearly any book I could think of – and was still committed to trying to read the sorts of books I thought I should enjoy rather than what I actually did – I skimmed a couple of Žižek’s works, including First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (2009), which arose from 9/11 and the global financial crisis and questions whether we can ever stop history repeating itself without undermining capitalism.

#1 One of the peripheral characters in Ozeki’s novel is an Eastern European philosopher who goes by “The Bottleman.” I had to wonder if he was based on avant-garde Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Back in 2010, when I was working at a university library in London and had access to nearly any book I could think of – and was still committed to trying to read the sorts of books I thought I should enjoy rather than what I actually did – I skimmed a couple of Žižek’s works, including First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (2009), which arose from 9/11 and the global financial crisis and questions whether we can ever stop history repeating itself without undermining capitalism.

#2 In searching my archives for farces I’ve read, I came across one I took notes on but never wrote up back in 2013: Japanese by Spring by Ishmael Reed (1993), an academic comedy set at “Jack London College” in Oakland, California. The novel satirizes almost every ideology prevalent in the 1960s–80s: multiculturalism, racism, xenophobia, nationalism, feminism, affirmative action and various literary critical methods. Reed sets up exaggerated and polarized groups and opinions. (You know it’s not to be taken entirely seriously when you see character names like Chappie Puttbutt, President Stool and Professor Poop, short for Poopovich.) The college is sold off to the Japanese and Ishmael Reed himself becomes a character. There are some amusing lines but I ended up concluding that Reed wasn’t for me. If you’ve enjoyed work by Paul Beatty and Percival Everett, he might be up your street.

#2 In searching my archives for farces I’ve read, I came across one I took notes on but never wrote up back in 2013: Japanese by Spring by Ishmael Reed (1993), an academic comedy set at “Jack London College” in Oakland, California. The novel satirizes almost every ideology prevalent in the 1960s–80s: multiculturalism, racism, xenophobia, nationalism, feminism, affirmative action and various literary critical methods. Reed sets up exaggerated and polarized groups and opinions. (You know it’s not to be taken entirely seriously when you see character names like Chappie Puttbutt, President Stool and Professor Poop, short for Poopovich.) The college is sold off to the Japanese and Ishmael Reed himself becomes a character. There are some amusing lines but I ended up concluding that Reed wasn’t for me. If you’ve enjoyed work by Paul Beatty and Percival Everett, he might be up your street.

#3 “Call me Ishmael” – even if, like me, you have never gotten through Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851), you probably know that famous opening line. I took an entire course on Nathaniel Hawthorne and Melville as an undergraduate and still didn’t manage to read the whole thing! Even my professor acknowledged that Melville could have done with a really good editor to rein in his ideas and cut out some of his digressions.

#3 “Call me Ishmael” – even if, like me, you have never gotten through Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851), you probably know that famous opening line. I took an entire course on Nathaniel Hawthorne and Melville as an undergraduate and still didn’t manage to read the whole thing! Even my professor acknowledged that Melville could have done with a really good editor to rein in his ideas and cut out some of his digressions.

#4 A favourite that I can recommend instead is Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn (2011). It’s just the kind of random, wide-ranging nonfiction I love: part memoir, part travelogue, part philosophical musing on human culture and our impact on the environment. In 1992 a pallet of “Friendly Floatees” bath toys fell off a container ship in a storm in the North Pacific. Over the next two decades those thousands of plastic animals made their way around the world, informing oceanographic theory and delighting children. Hohn’s obsessive quest for the origin of the bath toys and the details of their high seas journey takes on the momentousness of his literary antecedent. He visits a Chinese factory and sees plastics being made; he volunteers on a beach-cleaning mission in Alaska. (I’d not seen the Ozeki cover that appears in Kate’s post, but how pleasing to note that it also has a rubber duck on it!)

#4 A favourite that I can recommend instead is Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn (2011). It’s just the kind of random, wide-ranging nonfiction I love: part memoir, part travelogue, part philosophical musing on human culture and our impact on the environment. In 1992 a pallet of “Friendly Floatees” bath toys fell off a container ship in a storm in the North Pacific. Over the next two decades those thousands of plastic animals made their way around the world, informing oceanographic theory and delighting children. Hohn’s obsessive quest for the origin of the bath toys and the details of their high seas journey takes on the momentousness of his literary antecedent. He visits a Chinese factory and sees plastics being made; he volunteers on a beach-cleaning mission in Alaska. (I’d not seen the Ozeki cover that appears in Kate’s post, but how pleasing to note that it also has a rubber duck on it!)

#5 Alongside Moby-Duck on my “uncategorizable” Goodreads shelf is The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen (1978), one of my Books of Summer from 2019. A nature/travel classic that turns into something more like a spiritual memoir, it’s about a trip to Nepal in 1973, with Matthiessen joining a zoologist to study Himalayan blue sheep – and hoping to spot the elusive snow leopard. He had recently lost his partner to cancer, and relied on his Buddhist training to remind himself of tenets of acceptance and transience.

#5 Alongside Moby-Duck on my “uncategorizable” Goodreads shelf is The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen (1978), one of my Books of Summer from 2019. A nature/travel classic that turns into something more like a spiritual memoir, it’s about a trip to Nepal in 1973, with Matthiessen joining a zoologist to study Himalayan blue sheep – and hoping to spot the elusive snow leopard. He had recently lost his partner to cancer, and relied on his Buddhist training to remind himself of tenets of acceptance and transience.

#6 Ruth Padel is one of my favourite contemporary poets and a fixture at the New Networks for Nature conference I attend each year. She has a collection named The Soho Leopard (2004), whose title sequence is about urban foxes. The natural world and her travels are always a major element of her books. From one Ruth to another, then, by way of philosophy, farce, whaling, rubber ducks and mountain adventuring.

#6 Ruth Padel is one of my favourite contemporary poets and a fixture at the New Networks for Nature conference I attend each year. She has a collection named The Soho Leopard (2004), whose title sequence is about urban foxes. The natural world and her travels are always a major element of her books. From one Ruth to another, then, by way of philosophy, farce, whaling, rubber ducks and mountain adventuring.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point is a wildcard: use the book you finished with this month (or, if you haven’t done an August chain, the last book you’ve read).

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Booker Prize Longlist Thoughts and Reading Plan

Yesterday the 2022 Booker Prize longlist was announced.

It’s an intriguing selection that for the most part avoids the usual suspects – although a few of these authors have previously been shortlisted, they’re not from the standard crop of staid white men. The website is making much of two pieces of trivia: that the longlist includes the youngest and oldest authors ever (Leila Mottley at 20 and Alan Garner at 87); and that Small Things Like These is the shortest book to be nominated.

I happen to have read two from the longlist so far, and I’m surprised by how many of the rest I want to read. I’ll go through each of the ‘Booker Dozen’ of 13 below (the brief summaries are from the Booker Prize announcement e-mail):

Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo

“This energetic and exhilarating joyride … is the story of an uprising, told by a vivid chorus of animal voices that help us see our human world more clearly.”

- Zimbabwean author Bulawayo was shortlisted for her debut novel, We Need New Names, in 2013. I’ve never been drawn to read that one, and have to wonder why we needed an extended Animal Farm remake…

Trust by Hernan Diaz

“A literary puzzle about money, power, and intimacy, Trust challenges the myths shrouding wealth, and the fictions that often pass for history.”

- I’m looking forward to this one after all the buzz from its U.S. release, and have a copy on the way to me from Picador.

The Trees by Percival Everett

“A violent history refuses to be buried in … Everett’s striking novel, which combines an unnerving murder mystery with a powerful condemnation of racism and police violence.”

- Susan is a fan of Everett’s. He’s known for his satirical fiction, whereas the only book of his that I happen to have read was poetry – not representative of his work. I’d happily read this if given the chance, but Everett’s stuff is hard to find over here.

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

“Fowler’s epic novel about an ill-fated family of thespians, drinkers and dreamers, whose most infamous son is destined to commit a terrible and violent act.”

- I reviewed this for BookBrowse earlier in the year. (It’s Fowler’s second nomination, after We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, a very different novel.) The present-tense narration helps it be less of a dull group biography, and there are two female point-of-view characters. The issues of racial equality, political divisions and mistrust of the government are just as important in our own day. However, the foreshadowing is sometimes heavy-handed, the extended timeline means there is some skating over of long periods, and the novel as a whole is low on scenes and dialogue, with Fowler conveying a lot of information through exposition. I gave it a tepid

.

.

Treacle Walker by Alan Garner

“This latest fiction from a remarkable and enduring talent brilliantly illuminates an introspective young mind trying to make sense of the world around him.”

- Garner is a beloved fantasy writer in the UK. Though I didn’t care for The Owl Service when I read it in 2019, given that this is just over 150 pages, there would be no harm in taking a chance on it.

Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka

“Karunatilaka’s rip-roaring epic is a searing, mordantly funny satire set amid the murderous mayhem of a Sri Lanka beset by civil war.”

- This is the sort of Commonwealth novel I’m wary of, fearing Rushdie-like indulgence. My library system tends to order all the Booker nominees, so I would gladly borrow this and try the early pages to see how I get on.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

“Keegan’s tender tale of hope and quiet heroism is both a celebration of compassion and a stern rebuke of the sins committed in the name of religion.”

- I read and reviewed this late last year and appreciated it as a spare and heartwarming yuletide fable. A coal merchant in 1980s Ireland comes to value his quiet family life all the more when he sees how difficult existence is for the teen mothers sent to work in the local convent’s laundry service. I was familiar with the Magdalene Laundries from the movie The Magdalene Sisters and found this a fairly predictable narrative, with the nuns cartoonishly villainous. So I’m not as enthusiastic as many others have been, but feel like a Scrooge for saying so.

Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet

“Graeme Macrae Burnet offers a dazzlingly inventive – and often wickedly humorous – meditation on the nature of sanity, identity and truth itself.”

- Macrae Burnet was a dark horse in the 2016 Booker race for the terrific His Bloody Project. This new novel was one of Clare’s top picks for the longlist and sounds like a clever and playful book about a psychoanalyst and his patient; again the author blends fact and fiction and relies on ‘found documents’. I have it on request from the library.

The Colony by Audrey Magee

“In … Magee’s lyrical and brooding fable, two outsiders visit a small island off the west coast of Ireland, with unforeseen and haunting consequences.”

- One of Clare and Susan’s joint correct predictions (Susan’s review). On the face of it, it sounds too similar to one I read from last year’s longlist, An Island. I can’t say I’m particularly interested, though if this were to be shortlisted I might have a go.

Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer

“Under attack from within, Lia tries to keep the landscapes of her past, her present and her body separate. But time and bodies are porous, and unpredictable.”

- This Desmond Elliott Prize winner was already on my TBR for its medical theme and is one of two nominees I’m most excited about. It potentially sounds long and challenging, but has been received well by my Goodreads friends. I’ll hope my library system acquires a copy soon.

Nightcrawling by Leila Mottley

“At once agonising and mesmerising, Nightcrawling presents a haunting vision of marginalised young people navigating the darkest corners of an adult world.”

- Like many, I had this brought to my attention anew by Ruth Ozeki’s shout-out during her Women’s Prize acceptance speech (Mottley was her student). I’d already heard some chatter about it from its Oprah’s Book Club selection. The subject matter – sex workers in Oakland, California – will be tough, but I hope the prose and storytelling will make up for it. I have it on request from the library.

After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz

“A joyous reimagining of the lives of a brilliant group of feminists, sapphists, artists and writers from the past, as they battle for control over their lives, for liberation and for justice.”

- The other novel I’m most excited about. It was totally new to me but sounds fantastic. It only came out this month, so I’ll see if Galley Beggar might be willing to send out a review copy.

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

“Strout returns to her beloved heroine Lucy Barton in a luminous novel about love, loss, and the family secrets that can erupt and bewilder us at any time.”

- I DNFed this one after just 20 or so pages last year, finding Lucy too annoyingly scatter-brained this time around (I’d enjoyed My Name Is Lucy Barton but not read the sequel). But I’m willing to give it another try, so have placed a library hold.

There we have it: 2 read, 4 I have immediate plans to read, 3 I’m keen to read if I can find them, 4 I’m less likely to read – but, unlike in most years, there are no entries I’m completely uninterested in or averse to reading.

Earlier this year my book club took part in a Women’s Prize shadowing project run by the Reading Agency. They’re organizing a similar thing on behalf of the Booker Prize, but the six groups (for six shortlisted books) will be chosen by the Prize organizers this time, so we’ve been encouraged to apply again. It’s a better deal in that members of successful groups will be invited to attend the shortlist party and then the awards ceremony. I’ll meet up with my co-leader later this week to work on our application.

What have you read from the longlist? Which book(s) do you most want to find?

Book Serendipity, March to April 2022

This is a bimonthly feature of mine. I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. Because I usually 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

(I always like hearing about your bookish coincidences, too! Laura had what she thought must be the ultimate Book Serendipity when she reviewed two novels with the same setup: Groundskeeping by Lee Cole and Last Resort by Andrew Lipstein.)

- The same sans serif font is on Sea State by Tabitha Lasley and Lean Fall Stand by Jon McGregor – both released by 4th Estate. I never would have noticed had they not ended up next to each other in my stack one day. (Then a font-alike showed up in my TBR pile, this time from different publishers, later on: What Strange Paradise by Omar El Akkad and When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo.)

- Kraftwerk is mentioned in The Facebook of the Dead by Valerie Laws and How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu.

- The fact that bacteria sometimes form biofilms is mentioned in Hybrid Humans by Harry Parker and Slime by Susanne Wedlich.

- The idea that when someone dies, it’s like a library burning is repeated in The Reactor by Nick Blackburn and In the River of Songs by Susan Jackson.

- Espresso martinis are consumed in If Not for You by Georgina Lucas and Wahala by Nikki May.

- Prosthetic limbs turn up in Groundskeeping by Lee Cole, The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, and Hybrid Humans by Harry Parker.

- A character incurs a bad cut to the palm of the hand in After You’d Gone by Maggie O’Farrell and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki – I read the two scenes on the same day.

- Catfish is on the menu in Groundskeeping by Lee Cole and in one story of Antipodes by Holly Goddard Jones.

Reading two novels with “Paradise” in the title (and as the last word) at the same time: Paradise by Toni Morrison and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

Reading two novels with “Paradise” in the title (and as the last word) at the same time: Paradise by Toni Morrison and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

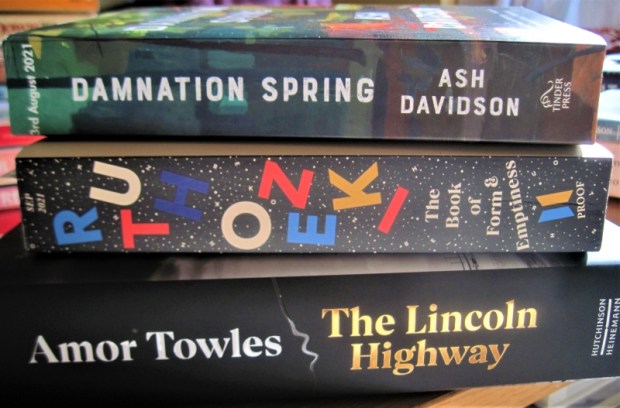

- Reading two books by a Davidson at once: Damnation Spring by Ash and Tracks by Robyn.

- There’s a character named Elwin in The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade and one called Elvin in The Two Lives of Sara by Catherine Adel West.

- Tea is served with lemon in The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald and The Two Lives of Sara by Catherine Adel West.

- There’s a Florence (or Flo) in Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin, These Days by Lucy Caldwell and Pictures from an Institution by Randall Jarrell. (Not to mention a Flora in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich.)

There’s a hoarder character in Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

There’s a hoarder character in Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- Reading at the same time two memoirs by New Yorker writers releasing within two weeks of each other (in the UK at least) and blurbed by Jia Tolentino: Home/Land by Rebecca Mead and Lost & Found by Kathryn Schulz.

- Three children play in a graveyard in Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier and Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith.

- Shalimar perfume is worn in These Days by Lucy Caldwell and The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade.

- A relative is described as “very cold” and it’s wondered what made her that way in Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso and one of the testimonies in Regrets of the Dying by Georgina Scull.

Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild is mentioned in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which I was reading at around the same time. (As is The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, which I’d recently finished.)

Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild is mentioned in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which I was reading at around the same time. (As is The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald, which I’d recently finished.)

- From one poetry collection with references to Islam (Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire) to another (Auguries of a Minor God by Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe).

- Two children’s books featuring a building that is revealed to be a theatre: Moominsummer Madness by Tove Jansson and The Unadoptables by Hana Tooke.

- Reading two “braid” books at once: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer and French Braid by Anne Tyler.

- Protests and teargas in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- Jellyfish poems in Honorifics by Cynthia Miller and Love Poems in Quarantine by Sarah Ruhl.

- George Floyd’s murder is a major element in The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and Love Poems in Quarantine by Sarah Ruhl.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

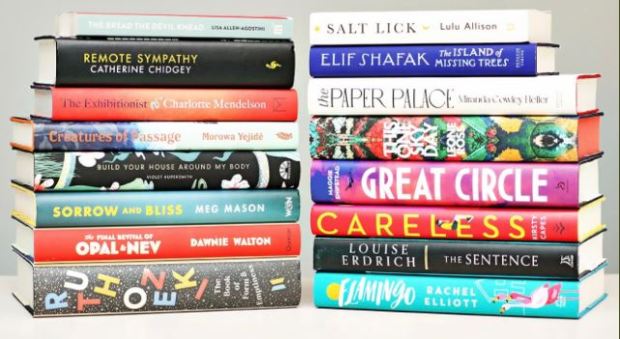

Quick Thoughts on the Women’s Prize 2022 Longlist & My Reading Plans

Tuesday is my volunteering morning at the library, but at 9:45 I nipped onto one of the public access PCs so I could find out which books were on the Women’s Prize longlist. I just couldn’t wait until I got home! It’s a surprising list. Those who thought Rooney and Yanagihara would be snubbed were absolutely right. Debuts and historical fiction aren’t as plentiful as forecast, but there are two doorstoppers on there, plus another 450+-pager. And it is great to see a list that is half by BIPOC women.

Of my wishes and predictions, 1 and 2 were correct, so I got 3 right overall, with my wildcard choice being the only nominee I’ve read in full so far. I’m currently reading another 2 and have 3 more set to read – the moment I got the news I marched over to borrow a couple more.

Fair play to the judges – I hadn’t even HEARD of these SIX titles:

- The Bread the Devil Knead by Lisa Allen-Agostini

- Salt Lick by Lulu Allison

- Careless by Kirsty Capes

- Remote Sympathy by Catherine Chidgey

- Flamingo by Rachel Elliott

- Creatures of Passage by Morowa Yejidé

I haven’t had a chance to look into these half-dozen, but will do so later on. I’m only likely to pick them up if a) others rave about them and/or b) they’re shortlisted.

Read:

Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason: They say turning 40 can do weird things to you. Martha Friel gets a tattoo – so far, so stereotypical – but also blows up her marriage to Patrick, who’s been devoted to her since they were teens and met as family friends. In the year that follows, she looks back on a life that’s been defined by mental illness. As a young woman she was told she should never have children, but recently she met a new psychiatrist who gave her a proper diagnosis and told her motherhood was not out of the question. But is it too late for Martha and Patrick? Martha’s narration is a delight, wry and deadpan but also with moments of wrenching emotion. Her relationship with her sister, Ingrid, who gives birth to her first child on their aunt’s bathroom floor and eventually has four under the age of nine, is a highlight, and it’s touching to see how their mother and their aunt, both initially standoffish, end up being pillars of support. (My full review)

Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason: They say turning 40 can do weird things to you. Martha Friel gets a tattoo – so far, so stereotypical – but also blows up her marriage to Patrick, who’s been devoted to her since they were teens and met as family friends. In the year that follows, she looks back on a life that’s been defined by mental illness. As a young woman she was told she should never have children, but recently she met a new psychiatrist who gave her a proper diagnosis and told her motherhood was not out of the question. But is it too late for Martha and Patrick? Martha’s narration is a delight, wry and deadpan but also with moments of wrenching emotion. Her relationship with her sister, Ingrid, who gives birth to her first child on their aunt’s bathroom floor and eventually has four under the age of nine, is a highlight, and it’s touching to see how their mother and their aunt, both initially standoffish, end up being pillars of support. (My full review)

Currently reading:

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith – I’m just over half done, and loving it. A weird and magical and slightly horror-tinged story set in Vietnam past and present, it builds on her debut ghost stories. Sort of plays the role Our Wives Under the Sea would have had on the longlist (though I dearly wish it could have been nominated as well).

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith – I’m just over half done, and loving it. A weird and magical and slightly horror-tinged story set in Vietnam past and present, it builds on her debut ghost stories. Sort of plays the role Our Wives Under the Sea would have had on the longlist (though I dearly wish it could have been nominated as well).

Set aside last year because it’s twee and annoying, but will now continue (ARGH + le sigh):

Set aside last year because it’s twee and annoying, but will now continue (ARGH + le sigh):

The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

Own and will read soon (this was a treat to self with birthday money last year):

Own and will read soon (this was a treat to self with birthday money last year):

The Final Revival of Opal and Nev by Dawnie Walton

Borrowed from library:

Borrowed from library:

The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

DNFed last year (twice); will not attempt again:

DNFed last year (twice); will not attempt again:

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

On request from the library:

On request from the library:

The Sentence by Louise Erdrich

The Exhibitionist by Charlotte Mendelson

Not interested in reading:

This One Sky Day by Leone Ross – I saw Ross speak about this and read an excerpt as part of a Faber showcase. I have a limited tolerance for magic realism and don’t think this appeals.

Above: my reading plans. Plenty to be getting on with before the shortlist announcement on 27th April!

What have you read, or might you read, from the longlist?

Book Serendipity, September to October 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20–30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck. This used to be a quarterly feature, but to keep the lists from getting too unwieldy I’ve shifted to bimonthly.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Young people studying An Inspector Calls in Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi and Heartstoppers, Volume 4 by Alice Oseman.

- China Room (Sunjeev Sahota) was immediately followed by The China Factory (Mary Costello).

- A mention of acorn production being connected to the weather earlier in the year in Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian and Noah’s Compass by Anne Tyler.

- The experience of being lost and disoriented in Amsterdam features in Flesh & Blood by N. West Moss and Yearbook by Seth Rogen.

- Reading a book about ravens (A Shadow Above by Joe Shute) and one by a Raven (Fox & I by Catherine Raven) at the same time.

- Speaking of ravens, they’re also mentioned in The Elements by Kat Lister, and the Edgar Allan Poe poem “The Raven” was referred to and/or quoted in both of those books plus 100 Poets by John Carey.

- A trip to Mexico as a way to come to terms with the death of a loved one in This Party’s Dead by Erica Buist (read back in February–March) and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading from two Carcanet Press releases that are Covid-19 diaries and have plague masks on the cover at the same time: Year of Plagues by Fred D’Aguiar and 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici. (Reviews of both coming up soon.)

- Descriptions of whaling and whale processing and a summary of the Jonah and the Whale story in Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs and The Woodcock by Richard Smyth.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

- After having read two whole nature memoirs set in England’s New Forest (Goshawk Summer by James Aldred and The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell), I encountered it again in one chapter of A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Cranford is mentioned in Corduroy by Adrian Bell and Cut Out by Michèle Roberts.

- Kenneth Grahame’s life story and The Wind in the Willows are discussed in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading two books by a Jenn at the same time: Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Other Mothers by Jenn Berney.

- A metaphor of nature giving a V sign (that’s equivalent to the middle finger for you American readers) in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- Quince preserves are mentioned in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- There’s a gooseberry pie in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo.

- The ominous taste of herbicide in the throat post-spraying shows up in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

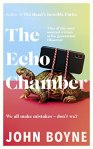

- People’s rude questioning about gay dads and surrogacy turns up in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and the DAD anthology from Music.Football.Fatherhood.

- A young woman dresses in unattractive secondhand clothes in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A mention of the bounty placed on crop-eating birds in medieval England in Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates and A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Hedgerows being decimated, and an account of how mistletoe is spread, in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- Listening to a dual-language presentation and observing that the people who know the original language laugh before the rest of the audience in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A character imagines his heart being taken out of his chest in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- A younger sister named Nina in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and Sex Cult Nun by Faith Jones.

- Adulatory words about George H.W. Bush in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Thinking Again by Jan Morris.

- Reading three novels by Australian women at the same time (and it’s rare for me to read even one – availability in the UK can be an issue): Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason, The Performance by Claire Thomas, and The Weekend by Charlotte Wood.

- There’s a couple who met as family friends as teenagers and are still (on again, off again) together in Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- The Performance by Claire Thomas is set during a performance of the Samuel Beckett play Happy Days, which is mentioned in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

- Nicholas Royle (whose White Spines I was also reading at the time) turns up on a Zoom session in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

- Richard Brautigan is mentioned in both The Mystery of Henri Pick by David Foenkinos and White Spines by Nicholas Royle.

- The Wizard of Oz and The Railway Children are part of the plot in The Book Smugglers (Pages & Co., #4) by Anna James and mentioned in Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

October Reading Plans and Books to Catch Up On

My plans for this month’s reading include:

Autumn-appropriate titles & R.I.P. selections, pictured below.

October releases, including some poetry and the debut memoir by local nature writer Nicola Chester – some of us are going on a book club field trip to see her speak about it in Hungerford on Saturday.

October releases, including some poetry and the debut memoir by local nature writer Nicola Chester – some of us are going on a book club field trip to see her speak about it in Hungerford on Saturday.

A review book backlog dating back to July. Something like 18 books, I think? A number of them also fall into the set-aside category, below.

An alarming number of doorstoppers:

- Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson (a buddy read underway with Marcie of Buried in Print; technically it’s 442 pages, but the print is so danged small that I’m calling it a doorstopper even though my usual minimum is 500 pages)

- The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki (in progress for blog review)

- Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead (a library hold on its way to me to try again now that it’s on the Booker Prize shortlist)

- The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles (in progress for BookBrowse review)

Also, I’m aware that we’re now into the last quarter of the year, and my “set aside temporarily” shelf – which is the literal top shelf of my dining room bookcase, as well as a virtual Goodreads shelf – is groaning with books that I started earlier in the year (or, in some cases, even late last year) and for whatever reason haven’t finished yet.

Setting books aside is a dangerous habit of mine, because new arrivals, such as from the library or from publishers, and more timely-seeming books always edge them out. The only way I have a hope of finishing these before the end of the year is to a) include them in challenges wherever possible (so a few long-languishing books have gone up to join my novella stacks in advance of November) and b) reintroduce a certain number to my current stacks at regular intervals. With just 13 weeks or so remaining, two per week seems like the necessary rate.

Do you have realistic reading goals for the final quarter of the year? (Or no goals at all?)

“Until the future, whatever it was going to be.” (This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub)

“Until the future, whatever it was going to be.” (This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub)

for me)

for me)

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

Tookie, the narrator, has a tough exterior but a tender heart. When she spent 10 years in prison for a misunderstanding-cum-body snatching, books helped her survive, starting with the dictionary. Once she got out, she translated her love of words into work as a bookseller at

Tookie, the narrator, has a tough exterior but a tender heart. When she spent 10 years in prison for a misunderstanding-cum-body snatching, books helped her survive, starting with the dictionary. Once she got out, she translated her love of words into work as a bookseller at  Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties.

Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties. What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working, and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was utterly rewarding.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working, and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was utterly rewarding. Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks: In 1665, with the Derbyshire village of Eyam in the grip of the Plague, the drastic decision is made to quarantine it. Frustration with the pastor’s ineffectuality attracts people to religious extremism. Anna’s intimate first-person narration and the historical recreation are faultless, and there are so many passages that feel apt.

Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks: In 1665, with the Derbyshire village of Eyam in the grip of the Plague, the drastic decision is made to quarantine it. Frustration with the pastor’s ineffectuality attracts people to religious extremism. Anna’s intimate first-person narration and the historical recreation are faultless, and there are so many passages that feel apt. Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler: Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin. Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? This is a book full of nostalgia and small-town atmosphere. All the characters wonder whether they’ve made the right decisions or gotten stuck. A lot of bittersweet moments, but also comic ones.

Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler: Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin. Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? This is a book full of nostalgia and small-town atmosphere. All the characters wonder whether they’ve made the right decisions or gotten stuck. A lot of bittersweet moments, but also comic ones. Kindred by Octavia E. Butler: A perfect time-travel novel for readers who quail at science fiction. Dana, an African American writer in Los Angeles, is dropped into early-nineteenth-century Maryland. This was such an absorbing read, with first-person narration that makes you feel you’re right there alongside Dana on her perilous travels.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler: A perfect time-travel novel for readers who quail at science fiction. Dana, an African American writer in Los Angeles, is dropped into early-nineteenth-century Maryland. This was such an absorbing read, with first-person narration that makes you feel you’re right there alongside Dana on her perilous travels. Dominicana by Angie Cruz: Ana Canción is just 15 when she arrives in New York from the Dominican Republic on the first day of 1965 to start her new life as the wife of Juan Ruiz. An arranged marriage and arriving in a country not knowing a word of the language: this is a valuable immigration story that stands out for its plucky and confiding narrator.

Dominicana by Angie Cruz: Ana Canción is just 15 when she arrives in New York from the Dominican Republic on the first day of 1965 to start her new life as the wife of Juan Ruiz. An arranged marriage and arriving in a country not knowing a word of the language: this is a valuable immigration story that stands out for its plucky and confiding narrator. Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn: A book of letters in multiple sense. Laugh-out-loud silliness plus a sly message about science and reason over superstition = a rare combination that made this an enduring favorite. On my reread I was more struck by the political satire: freedom of speech is endangered in a repressive society slavishly devoted to a sacred text.

Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn: A book of letters in multiple sense. Laugh-out-loud silliness plus a sly message about science and reason over superstition = a rare combination that made this an enduring favorite. On my reread I was more struck by the political satire: freedom of speech is endangered in a repressive society slavishly devoted to a sacred text. Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich: Interlocking stories that span half a century in the lives of a couple of Chippewa families that sprawl out from a North Dakota reservation. Looking for love, looking for work. Getting lucky, getting even. Their problems are the stuff of human nature and contemporary life. I adored the descriptions of characters and of nature.

Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich: Interlocking stories that span half a century in the lives of a couple of Chippewa families that sprawl out from a North Dakota reservation. Looking for love, looking for work. Getting lucky, getting even. Their problems are the stuff of human nature and contemporary life. I adored the descriptions of characters and of nature. Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale: Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of a bipolar artist and her interactions with her husband and children. Their Quakerism sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows family secrets to proliferate. The novel questions patterns of inheritance and the possibility of happiness.

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale: Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of a bipolar artist and her interactions with her husband and children. Their Quakerism sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows family secrets to proliferate. The novel questions patterns of inheritance and the possibility of happiness. Confession with Blue Horses by Sophie Hardach: When Ella’s parents, East German art historians who came under Stasi surveillance, were caught trying to defect, their children were taken away from them. Decades later, Ella is determined to find her missing brother and learn what really happened to her mother. Eye-opening and emotionally involving.

Confession with Blue Horses by Sophie Hardach: When Ella’s parents, East German art historians who came under Stasi surveillance, were caught trying to defect, their children were taken away from them. Decades later, Ella is determined to find her missing brother and learn what really happened to her mother. Eye-opening and emotionally involving. The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley: Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend July at his school friend’s home, Brandham Hall. You know from the famous first line on that this juxtaposes past and present. It’s masterfully done: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches.

The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley: Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend July at his school friend’s home, Brandham Hall. You know from the famous first line on that this juxtaposes past and present. It’s masterfully done: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches. Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf: Addie is a widow; Louis is a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to fretting about what they could have done better. Would he like to come over to her house at night to talk and sleep? Matter-of-fact prose, delivered without speech marks, belies a deep undercurrent of emotion. Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect.

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf: Addie is a widow; Louis is a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to fretting about what they could have done better. Would he like to come over to her house at night to talk and sleep? Matter-of-fact prose, delivered without speech marks, belies a deep undercurrent of emotion. Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect. The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud: A 9/11 novel. The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up; now it’s time to get out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassess what is admirable and who is expendable. This was thoroughly engrossing. Great American Novel territory, for sure.

The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud: A 9/11 novel. The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up; now it’s time to get out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassess what is admirable and who is expendable. This was thoroughly engrossing. Great American Novel territory, for sure. My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki: A Japanese-American filmmaker is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. There is a clear message here about cheapness and commodification, but Ozeki filters it through the wrenching stories of two women with fertility problems. Bold if at times discomforting.

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki: A Japanese-American filmmaker is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. There is a clear message here about cheapness and commodification, but Ozeki filters it through the wrenching stories of two women with fertility problems. Bold if at times discomforting. Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields: An impeccable novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes. Something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, it’s laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life.

Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields: An impeccable novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes. Something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, it’s laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Larry’s Party by Carol Shields: The sweep of Larry’s life, from youth to middle age, is presented chronologically through chapters that are more like linked short stories: they focus on themes (family, friends, career, sex, clothing, health) and loop back to events to add more detail and new insight. I found so much to relate to in Larry’s story; Larry is really all of us.

Larry’s Party by Carol Shields: The sweep of Larry’s life, from youth to middle age, is presented chronologically through chapters that are more like linked short stories: they focus on themes (family, friends, career, sex, clothing, health) and loop back to events to add more detail and new insight. I found so much to relate to in Larry’s story; Larry is really all of us. Abide with Me by Elizabeth Strout: Tyler Caskey is a widowed pastor whose five-year-old daughter has gone mute and started acting up. As usual, Strout’s characters are painfully real, flawed people, often struggling with damaging obsessions. She tenderly probes the dark places of the community and its minister’s doubts, but finds the light shining through.

Abide with Me by Elizabeth Strout: Tyler Caskey is a widowed pastor whose five-year-old daughter has gone mute and started acting up. As usual, Strout’s characters are painfully real, flawed people, often struggling with damaging obsessions. She tenderly probes the dark places of the community and its minister’s doubts, but finds the light shining through. The Wife by Meg Wolitzer: On the way to Finland, where her genius writer husband will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. Alternating between the trip and earlier in their marriage, this is deceptively thoughtful with a juicy twist. Joan’s narration is witty and the point about the greater value attributed to men’s work is still valid.

The Wife by Meg Wolitzer: On the way to Finland, where her genius writer husband will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. Alternating between the trip and earlier in their marriage, this is deceptively thoughtful with a juicy twist. Joan’s narration is witty and the point about the greater value attributed to men’s work is still valid. Winter Journal by Paul Auster: Approaching age 64, the winter of his life, Auster decided to assemble his most visceral memories: scars, accidents and near-misses, what his hands felt and his eyes observed. The use of the second person draws readers in. I particularly enjoyed the tour through the 21 places he’s lived. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read.

Winter Journal by Paul Auster: Approaching age 64, the winter of his life, Auster decided to assemble his most visceral memories: scars, accidents and near-misses, what his hands felt and his eyes observed. The use of the second person draws readers in. I particularly enjoyed the tour through the 21 places he’s lived. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read. Heat by Bill Buford: Buford was an unpaid intern at Mario Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo. In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic sessions of food prep, Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London. Exactly what I want from food writing: interesting trivia, quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions.

Heat by Bill Buford: Buford was an unpaid intern at Mario Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo. In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic sessions of food prep, Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London. Exactly what I want from food writing: interesting trivia, quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions. Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins: Collins moved to Hay-on-Wye with his wife and toddler son, hoping to make a life there. As he edited the manuscript of his first book, he started working for Richard Booth, the eccentric bookseller who crowned himself King of Hay. Warm, funny, and nostalgic. An enduring favorite of mine.

Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins: Collins moved to Hay-on-Wye with his wife and toddler son, hoping to make a life there. As he edited the manuscript of his first book, he started working for Richard Booth, the eccentric bookseller who crowned himself King of Hay. Warm, funny, and nostalgic. An enduring favorite of mine. A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee: From a life spent watching birds, Dee weaves a mesh of memories and recent experiences, meditations and allusions. He moves from one June to the next and from Shetland to Zambia. The most powerful chapter is about watching peregrines at Bristol’s famous bridge – where he also, as a teen, saw a man commit suicide.

A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee: From a life spent watching birds, Dee weaves a mesh of memories and recent experiences, meditations and allusions. He moves from one June to the next and from Shetland to Zambia. The most powerful chapter is about watching peregrines at Bristol’s famous bridge – where he also, as a teen, saw a man commit suicide. The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange: While kayaking down the western coast of the British Isles and Ireland, Gange delves into the folklore, geology, history, local language and wildlife of each region and island group – from the extreme north of Scotland at Muckle Flugga to the southwest tip of Cornwall. An intricate interdisciplinary approach.

The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange: While kayaking down the western coast of the British Isles and Ireland, Gange delves into the folklore, geology, history, local language and wildlife of each region and island group – from the extreme north of Scotland at Muckle Flugga to the southwest tip of Cornwall. An intricate interdisciplinary approach. Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith by Anne Lamott: There is a lot of bereavement and other dark stuff here, yet an overall lightness of spirit prevails. A college dropout and addict, Lamott didn’t walk into a church and get clean until her early thirties. Each essay is perfectly constructed, countering everyday angst with a fumbling faith.

Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith by Anne Lamott: There is a lot of bereavement and other dark stuff here, yet an overall lightness of spirit prevails. A college dropout and addict, Lamott didn’t walk into a church and get clean until her early thirties. Each essay is perfectly constructed, countering everyday angst with a fumbling faith. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: This has my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scene, gleefully does away with chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory, and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to interrogate her experience of same-sex domestic violence. (Second-person narration again!)

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: This has my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scene, gleefully does away with chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory, and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to interrogate her experience of same-sex domestic violence. (Second-person narration again!) Period Piece by Gwen Raverat: Raverat was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. This is a portrait of what it was like to grow up in a particular time and place (Cambridge from the 1880s to about 1909). Not just an invaluable record of domestic history, it is a funny and impressively thorough memoir that serves as a model for how to capture childhood.

Period Piece by Gwen Raverat: Raverat was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. This is a portrait of what it was like to grow up in a particular time and place (Cambridge from the 1880s to about 1909). Not just an invaluable record of domestic history, it is a funny and impressively thorough memoir that serves as a model for how to capture childhood. The Universal Christ by Richard Rohr: I’d read two of the Franciscan priest’s previous books but was really blown away by the wisdom in this one. The argument in a nutshell is that Western individualism has perverted the good news of Jesus, which is renewal for everything and everyone. A real gamechanger. My copy is littered with Post-it flags.

The Universal Christ by Richard Rohr: I’d read two of the Franciscan priest’s previous books but was really blown away by the wisdom in this one. The argument in a nutshell is that Western individualism has perverted the good news of Jesus, which is renewal for everything and everyone. A real gamechanger. My copy is littered with Post-it flags. First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger: The octogenarian folk singer and activist has packed in enough adventure and experience for multiple lifetimes, and in some respects has literally lived two: one in America and one in England; one with Ewan MacColl and one with a female partner. Her writing is punchy and impressionistic. She’s my new hero.

First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger: The octogenarian folk singer and activist has packed in enough adventure and experience for multiple lifetimes, and in some respects has literally lived two: one in America and one in England; one with Ewan MacColl and one with a female partner. Her writing is punchy and impressionistic. She’s my new hero. A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas: A memoir in essays about her husband’s TBI and what kept her going. Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. It is one of the first memoirs I remember reading; it made a big impression the first time, but I loved it even more on a reread.

A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas: A memoir in essays about her husband’s TBI and what kept her going. Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. It is one of the first memoirs I remember reading; it made a big impression the first time, but I loved it even more on a reread. On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe: Explores the fragmentary history of the manmade Neolithic mound and various attempts to excavate it, but ultimately concludes we will never understand how and why it was made. A flawless integration of personal and wider history, as well as a profound engagement with questions of human striving and hubris.

On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe: Explores the fragmentary history of the manmade Neolithic mound and various attempts to excavate it, but ultimately concludes we will never understand how and why it was made. A flawless integration of personal and wider history, as well as a profound engagement with questions of human striving and hubris.