Winter Reads: Claire Tomalin, Daniel Woodrell & Picture Books

Mid-February approaches and we’re wondering if the snowdrops and primroses emerging here in the South of England mean that it will be farewell to winter soon, or if the cold weather will return as rumoured. (Punxsutawney Phil didn’t see his shadow, but that early-spring prediction is only valid for the USA, right?) I didn’t manage to read many seasonal books this year, but I did pick up several short works with “Winter” in the title: a little-known biographical play from a respected author, a gritty Southern Gothic novella made famous through a Jennifer Lawrence film, and two picture books I picked up at the library last week.

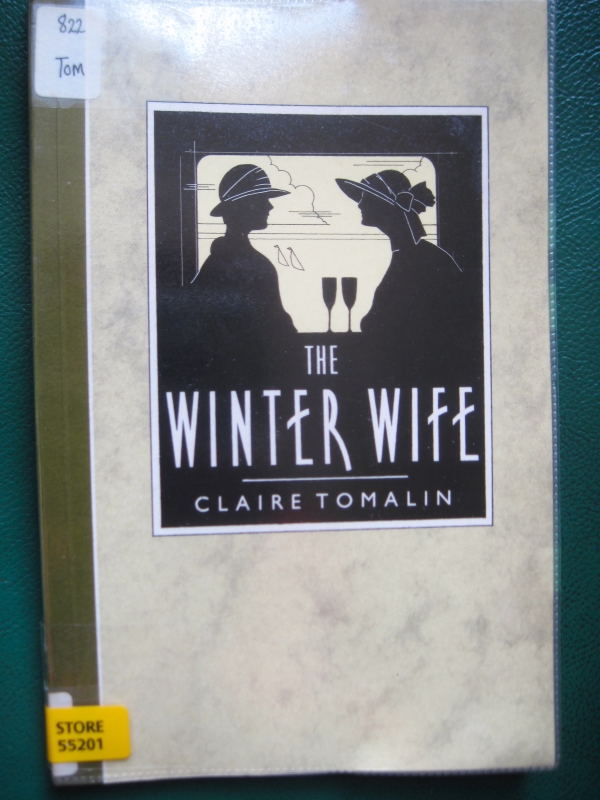

The Winter Wife by Claire Tomalin (1991)

A search of the university library catalogue turned up this Tomalin title I’d never heard of. It turns out to be a very short play (two acts of seven scenes each, but only running to 44 pages in total) about a trip abroad Katherine Mansfield took with her housekeeper?/companion, Ida Baker, in 1920. Ida clucks over Katherine like a nurse or mother hen, but there also seems to be latent, unrequited love there (Mansfield was bisexual, as I knew from fellow New Zealander Sarah Laing’s fab graphic memoir Mansfield and Me). Katherine, for her part, alternately speaks to Ida, whom she nicknames “Jones,” with exasperation and fondness. The title comes from a moment late on when Katherine tells Ida “you’re the perfect friend – more than a friend. You know what you are, you’re what every woman needs: you’re my true wife.” Maybe what we’d call a “work wife” today, but Ida blushes with pride.

Tomalin had already written a full-length biography of Mansfield, but insists she barely referred to it when composing this. The backdrops are minimal: a French sleeper train; Isola Bella, a villa on the French Riviera; and Dr. Bouchage’s office. Mansfield was ill with tuberculosis, and the continental climate was a balm: “The sun gets right into my bones and makes me feel better. All that English damp was killing me. I can’t think why I ever tried to live in England.” There are also financial worries. The Murrys keep just one servant, Marie, a middle-aged French woman who accompanies her on this trip, but Katherine fears they’ll have to let her go if she doesn’t keep earning by her pen.

Through Katherine’s conversations with the doctor, we catch up on her romantic history – a brief first marriage, a miscarriage, and other lovers. Dr. Bouchage believes her infertility is a result of untreated gonorrhea. He echoes Ida in warning Katherine that she’s working too hard – mostly reviewing books for her husband John Middleton Murry’s magazine, but also writing her own short stories – when she should be resting. Katherine retorts, “It is simply none of your business, Jones. Dr Bouchage: if I do not work, I might as well be dead, it’s as simple as that.”

She would die not three years later, a fact that audiences learn through a final flash-forward where Ida, in a monologue, contrasts her own long life (she lived to 90 and Tomalin interviewed her when she was 88) with Katherine’s short one. “I never married. For me, no one ever equalled Katie. There was something golden about her.” Whereas Katherine had mused, “I thought there was going to be so much life then … that it would all be experience I could use. I thought I could live all sorts of different lives, and be unscathed…”

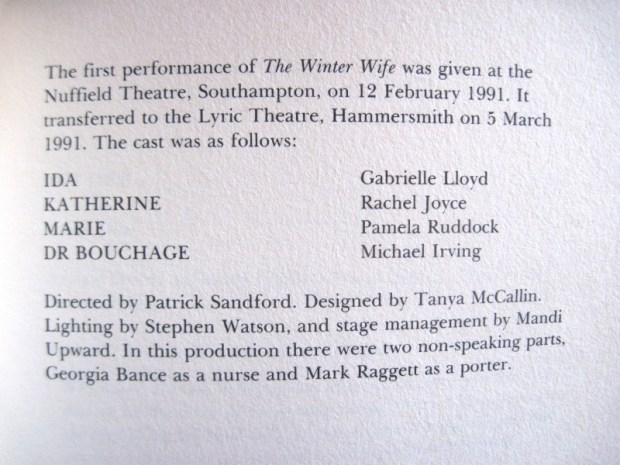

The play is, by its nature, slight, but gives a lovely sense of the subject and her key relationships – I do mean to read more by and about Mansfield. I wonder if it has been performed much since. And how about this for unexpected literary serendipity?

Yes, it’s that Rachel Joyce. (University library)

Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell (2006)

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

Forced to undertake a frozen odyssey to find traces of Jessup, she’s unwelcome everywhere she goes, even among extended family. No one is above hitting a girl, it seems, and just for asking questions Ree gets beaten half to death. Her only comfort is in her best friend, Gail, who’s recently given birth and married the baby daddy. Gail and Ree have long “practiced” on each other romantically. Without labelling anything, Woodrell sensitively portrays the different value the two girls place on their attachment. His prose is sometimes gorgeous –

Pine trees with low limbs spread over fresh snow made a stronger vault for the spirit than pews and pulpits ever could.

– but can be overblown or off-puttingly folksy:

Ree felt bogged and forlorn, doomed to a spreading swamp of hateful obligations.

Merab followed the beam and led them on a slow wamble across a rankled field

This was my second from Woodrell, after the short stories of The Outlaw Album. I don’t think I’ll need to try any more by him, but this was a solid read. (Secondhand – New Chapter Books, Wigtown)

Children’s picture books:

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

Bloggers’ Opinions Must Not Be Bought: A Cautionary Tale

I’m leery of accepting self-published work for review. If this is prejudice on my part, it’s not unjustified: I’ve reviewed hundreds of self-published books during my four years of freelance work for Kirkus, Foreword, BlueInk, Publishers Weekly, and The Bookbag, and although I do find the very occasional gem that could hold its own in a traditional market, the overall quality is poor. When self-published authors get in touch via my blog, I usually delete their enquiries immediately. But for some reason I decided to give a second look to a request I received through Goodreads earlier this year. (All identifying details have been removed.)

I’ll admit it: the flattery probably helped:

This was for a historical novel that had 4-star reviews from two Goodreads friends whose judgment I trust, so I agreed to have the author send a copy to my parents’ house in the States so that it would be waiting for me there when I arrived for my recent trip. When I opened the box, two alarm bells rang at once. First there was this. Uh oh.

![]()

Second of all: the author had taken the trouble of looking up restaurants in my parents’ area and ordered a $60 gift card from one of them to send along with the book parcel. Double uh oh.

I spent weeks wondering what in the world I was going to do about this ethical quandary. I even contacted a Goodreads friend who’d reviewed the book and asked what their experience with the author had been like. The reply was very telling:

I still feel unsettled over my interaction with [name redacted]. I’ve always made it a point not to review unsolicited books. But over a period of several weeks, [they] sent me a number of emails that ranged from flattering to fawning – and always polite and charming. Eventually, I, too, received a $60 gift card to a favorite restaurant that was within blocks of my home. I ended up, I believe, 4 starring [the] book, although the truth is that it was more of a 3-star read. Since reviewing, I have valued my independence – and honesty – and since then, have had the uncomfortable feeling of being “bought”, and for a low price at that.

I cannot tell you what to do. Obviously, I feel as if my own values were compromised. For me, it wasn’t worth what I still believe is a blot on my integrity. If you do decide to review, I’d simply encourage you to be honest because (I learned the hard way) the aftermath isn’t a good feeling.

Well, I’d promised to review the book, so I forced myself to open it, pencil in hand. After I’d corrected 10 problems of punctuation and grammar within the first six pages, I commenced skimming. There were some decent folksy metaphors and a not-half-bad dual narrative of a young woman’s odyssey and a small town’s feuds. But there were also dreadful sex scenes, melodramatic plot turns, and dialogue and slang that didn’t ring true for the time period. If I squinted pretty darn hard, I could see my way to likening the novel to the works of Ron Rash and Daniel Woodrell. But it wasn’t by any means a book I could genuinely recommend.

So when the author checked up a couple of months later to see whether I had gotten the book and what I thought of it, here’s what I replied:

I received the following abject apology, but no helpful information.

To my brief follow-up –

– I received this:

Note the phrase “self-promoted” and the meaningless repetition of “couldn’t put it down!”

And then they went on to disparage me for my age?!

I don’t believe for a minute that this person was ignorant of what they were doing in sending the gift cards. What’s saddest to me is that they have zero interest in getting an honest opinion of the work or hearing constructive criticism that could help them improve. They clearly don’t respect professionals’ estimation, either, or they’d be brave enough to pay for a review from Kirkus or another independent body. Instead, they’ve presumably been ‘paying’ $60 a pop to get fawning but utterly false 5-star reviews. Just imagine how much money they’ve spent on shipping and ‘thank-you gifts’ – easily many thousands of dollars.

And could I really have been the first in 180+ people to express misgivings about what was going on here? How worrying.

I was tempted to be generous and give the novel the briefest of 3-star reviews, perhaps as an addendum to another review on my blog, just so that I could feel justified in keeping the gift card and not have to face a confrontation with the author. But it didn’t feel right. If I want my reviews to have integrity, they have to reflect my honest opinions. As it stands, I have the gift card in an envelope, ready to be returned to the author when I’m in the States for my sister’s wedding next month; the book will most likely get dropped off at a Little Free Library.

If I was a vindictive person, I’d be going on Goodreads and Amazon and giving the book a 1-star review: as a necessary corrective to the bogus 5-star ones, and as a way of exposing this dodgy self-promotional activity. But that would in turn expose all of this person’s readers, including a valued Goodreads friend. And who knows how the author would try to retaliate.

So there you have it. My cautionary tale of a self-published author trying to buy my good opinion. What have I learned? Mostly to be even more wary of self-published work; possibly not to make any promises to review a book until I’ve seen a sample of it. But also to listen to my conscience and, when something is wrong, have the courage to speak out right away.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

Three corkers; two pretty good; four been-there-read-that. My favorites were the first and last stories, “Mrs Fox” and “Evie” (winner of the BBC National Short Story Prize 2013 and shortlisted for the Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award 2013, respectively). Both concern a fairly average marriage derailed when the wife undergoes a transformation. In the former Sophia literally turns into a fox and her husband scrambles for a way to make the relationship last. In “Evie,” Richard’s wife develops a voracious appetite for sweets and sex, and starts talking gibberish. This one is very explicit, but if you can get past that I found it both painful and powerful. I also especially liked “Case Study 2,” about a psychologist’s encounter with a boy who’s been brought up in a commune. It has faint echoes of T.C. Boyle’s “The Wild Child.”

Three corkers; two pretty good; four been-there-read-that. My favorites were the first and last stories, “Mrs Fox” and “Evie” (winner of the BBC National Short Story Prize 2013 and shortlisted for the Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award 2013, respectively). Both concern a fairly average marriage derailed when the wife undergoes a transformation. In the former Sophia literally turns into a fox and her husband scrambles for a way to make the relationship last. In “Evie,” Richard’s wife develops a voracious appetite for sweets and sex, and starts talking gibberish. This one is very explicit, but if you can get past that I found it both painful and powerful. I also especially liked “Case Study 2,” about a psychologist’s encounter with a boy who’s been brought up in a commune. It has faint echoes of T.C. Boyle’s “The Wild Child.”

Based on the first six stories, I was planning a 5-star rating. (How can you resist this opening line? “Once Boshell finally killed his neighbor he couldn’t seem to quit killing him.”) But the second half of the book ended up being much less memorable; I wouldn’t say it wasn’t worth reading, but I got very little out of four of the stories, and the other two were okay but somewhat insubstantial. By contrast, the first two stories, “The Echo of Neighborly Bones” and “Uncle,” are gritty little masterpieces of violence and revenge.

Based on the first six stories, I was planning a 5-star rating. (How can you resist this opening line? “Once Boshell finally killed his neighbor he couldn’t seem to quit killing him.”) But the second half of the book ended up being much less memorable; I wouldn’t say it wasn’t worth reading, but I got very little out of four of the stories, and the other two were okay but somewhat insubstantial. By contrast, the first two stories, “The Echo of Neighborly Bones” and “Uncle,” are gritty little masterpieces of violence and revenge. Bloom was a practicing psychotherapist, so it’s no surprise she has deep insight into her characters’ motivations. This is a wonderful set of stories about people who love who they shouldn’t love. In “Song of Solomon,” a new mother falls for the obstetrician who delivered her baby; in “Sleepwalking,” a woman gives in to the advances of her late husband’s son from a previous marriage; in “Light Breaks Where No Sun Shines,” adolescent Susan develops crushes on any man who takes an interest in her. My favorite was probably “Love Is Not a Pie,” in which a young woman rethinks her impending marriage during her mother’s funeral, all the while remembering the unusual sleeping arrangement her parents had with another couple during their joint summer vacations. The title suggests that love is not a thing to be apportioned out equally until it’s used up, but a more mysterious and fluid entity.

Bloom was a practicing psychotherapist, so it’s no surprise she has deep insight into her characters’ motivations. This is a wonderful set of stories about people who love who they shouldn’t love. In “Song of Solomon,” a new mother falls for the obstetrician who delivered her baby; in “Sleepwalking,” a woman gives in to the advances of her late husband’s son from a previous marriage; in “Light Breaks Where No Sun Shines,” adolescent Susan develops crushes on any man who takes an interest in her. My favorite was probably “Love Is Not a Pie,” in which a young woman rethinks her impending marriage during her mother’s funeral, all the while remembering the unusual sleeping arrangement her parents had with another couple during their joint summer vacations. The title suggests that love is not a thing to be apportioned out equally until it’s used up, but a more mysterious and fluid entity.

Simpson won the inaugural Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for this in 1991. Her protagonists are women disillusioned with the norms of marriage and motherhood. They ditch their safe relationships, or carry on brazen affairs; they fear pregnancy, or seek it out on their own terms. The feminist messages are never strident because they are couched in such brisk, tongue-in-cheek narratives. For instance, in “Christmas Jezebels” three sisters in 4th-century Lycia cleverly resist their father’s attempts to press them into prostitution and are saved by the bishop’s financial intervention; in “Escape Clauses” a middle-aged woman faces the death penalty for her supposed crimes of gardening naked and picnicking on private property, while her rapist gets just three months in prison because she was “asking for it.” (Nearly three decades on, it’s still so timely it hurts.)

Simpson won the inaugural Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for this in 1991. Her protagonists are women disillusioned with the norms of marriage and motherhood. They ditch their safe relationships, or carry on brazen affairs; they fear pregnancy, or seek it out on their own terms. The feminist messages are never strident because they are couched in such brisk, tongue-in-cheek narratives. For instance, in “Christmas Jezebels” three sisters in 4th-century Lycia cleverly resist their father’s attempts to press them into prostitution and are saved by the bishop’s financial intervention; in “Escape Clauses” a middle-aged woman faces the death penalty for her supposed crimes of gardening naked and picnicking on private property, while her rapist gets just three months in prison because she was “asking for it.” (Nearly three decades on, it’s still so timely it hurts.)