20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

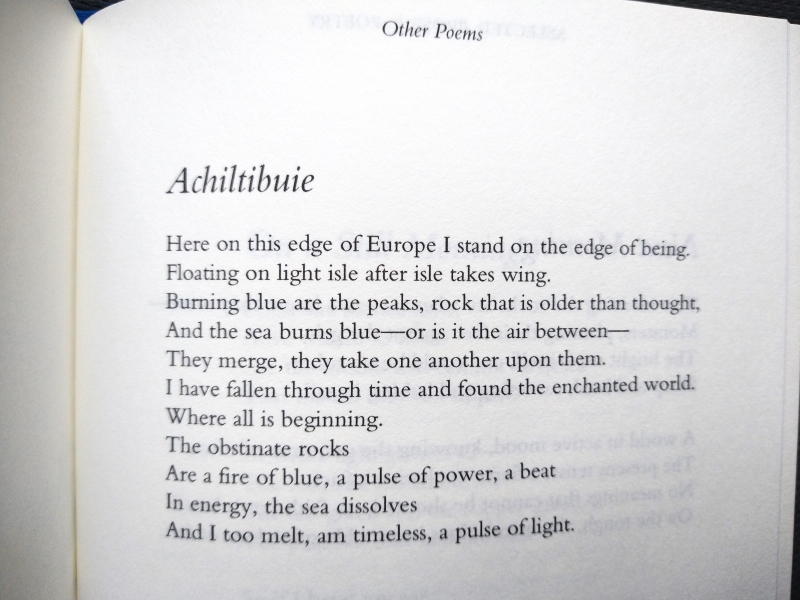

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

New Networks for Nature 2021 Conference in Bath

Hard to believe, but this past weekend was my seventh time attending the New Networks for Nature conference. It was held in Bath on this occasion, after a number of years in Stamford plus once each in Cambridge, York, and online (last year, of course). I happen to have written about it in most other years (2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 and 2020), and this year’s programme was so brilliant it would be a shame not to commemorate it. The weekend in Bath started off in a wonderful way: I was finally able to meet Susan of A life in books in person. We talked blogs and book prizes (and Covid and cats) over hot drinks by the Abbey square, and I even got her to sign my copy of her book, the Bloomsbury Essential Guide for Reading Groups.

Hard to believe, but this past weekend was my seventh time attending the New Networks for Nature conference. It was held in Bath on this occasion, after a number of years in Stamford plus once each in Cambridge, York, and online (last year, of course). I happen to have written about it in most other years (2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 and 2020), and this year’s programme was so brilliant it would be a shame not to commemorate it. The weekend in Bath started off in a wonderful way: I was finally able to meet Susan of A life in books in person. We talked blogs and book prizes (and Covid and cats) over hot drinks by the Abbey square, and I even got her to sign my copy of her book, the Bloomsbury Essential Guide for Reading Groups.

As I’ve mentioned before, what makes New Networks for Nature special is the interdisciplinary approach: artists, poets, musicians, activists, academics and conservationists attend and speak. The audience, let alone the speakers’ roster, is a who’s who of familiar names and faces from the UK nature writing world. So although the event might seem geared more towards my ecologist husband, there’s always plenty to interest me, too. The conference planners make ongoing efforts to diversify the programme: this year there were several all-female panels and seven BIPOC appeared on stage. It was a hybrid event in two senses: people could live-stream from home if not comfortable attending in person, and a few speakers appeared on the screen from locations as far-flung as India and New Zealand.

Exploring the Kennet & Avon canal (which also runs behind our house) one lunchtime. Photo by Chris Foster.

I hadn’t had much time to peruse the programme before the conference began. Without exception, the sessions surpassed my expectations. The opening event on the Friday evening was, fittingly, about the question of inclusivity. Nicola Chester, author of On Gallows Down; Anita Roy, part of the Transition Town Wellington movement and co-editor of Gifts of Gravity and Light; and David Lindo, known as “The Urban Birder,” had a discussion with Seb Choudhury about access to ‘the countryside’, which they agreed is perhaps an unhelpful term that discourages people from going out and experiencing the wildlife on their doorstep.

Saturday opened with a panel on art and environmental awareness. Harriet Mead welds sculptures out of found objects, Rachel Taylor is a scientist who makes birds out of glass, and Sarah Gillespie is a landscape painter whose prints of moths are so lifelike you’d swear they’re photographs. Gillespie spoke for all of them when she said that attention breaks down the dualism between self and other, creating an exchange of energies, with the artist serving as the watchman. These observations appeared to hold true for nature writing as well.

Scientists and writers alike commented on plastics in the environment and species migration. Did you know that 500,000 tons of plastic food packaging is created in the UK per year? Or that dolphins form allyships and have a culture? In the afternoon we met three teenage climate activists who have been involved in school strikes, COP26 protests, and volunteering to cultivate green spaces. Their public speaking ability was phenomenal. A final session of the day was with Julian Hector, head of the BBC Natural History Unit. He showed clips from some of the most famous nature documentaries made during his tenure and polled the room about how they feel about the use of music for emotional manipulation.

Speaking of music, the highlight of the conference came about due to the unlikely friendship between Mary Colwell, writer and curlew conservation activist, and singer/songwriter David Gray, who met her after he donated to one of her campaigns and has since gone along on one of her fundraising walks, narrated and scored a short documentary on curlews (you can watch it here), and contributed a song to a forthcoming RSPB-funded album inspired by curlews. We had the absolute treat of attending his first public performance in over two years on the Saturday evening at St Swithin’s Church, a venue that holds perhaps 200 people – versus next year he’ll be filling 20,000-seat stadiums for his White Ladder 20th anniversary tour.

This was carefully billed as an evening in conversation with David Gray rather than a gig, but in the end we got seven songs performed live at the church piano, as opposed to the three originally planned, so I call that a win! Other song excerpts were played over the sound system: “Let the Truth Sting” from his ‘angry young man’ phase, “Accumulates” as an anti-consumerism screed, and “Gulls” (based on an obscure Belgian poem) and “The Sapling” to illustrate how nature imagery enters into his lyrics.

Raised in Pembrokeshire, Gray loved going out on a fishing boat with his neighbours and seeing the seabirds massing around Skomer Island. He said he doesn’t think he’s ever gotten over those childhood experiences, and now he welcomes every sighting of a barn owl near his home in Norfolk (and encouraged us all to start gluing ourselves to roads). One of the songs he performed was indeed “The White Owl,” from Skellig, released early this year. Subtler than some of his albums, it was mostly recorded in a live setup and is built around simple, almost chant-like repeats and harmonies. That incantatory beauty was evident on another song he played live, “No False Gods,” which I didn’t realize has at its core a line from a Nan Shepherd poem: “We are love’s body or we are undone.”

Gray finished the official programme with his unreleased curlew song, “The Arc,” but came back for an encore of “Birds of the High Arctic,” “All that We Asked For” and “Sail Away” – this last to great cheers of recognition. He couldn’t figure out how to finish it after the whistling so just gave a few last plinks and then a hearty laugh as he returned to the stage to answer questions. We were impressed with his eloquence, sense of humour and BIG voice, especially on “Ain’t No Love” (from what has been our favourite of his albums, 2005’s Life in Slow Motion) – I got the feeling he barely needed a microphone to fill the whole church.

Sunday morning opened, appropriately, with a panel on nature and spirituality, featuring Satish Kumar, an octogenarian peace pilgrim to nuclear sites; Jini Reddy, author of Wanderland; and Nick Mayhew-Smith, who’s travelled to places of Celtic spirituality around the British Isles, such as hermits’ caves. Kumar led us in a meditation on gratitude and belonging, and suggested that we are all connected, and all spiritual, because we all share the same breath. He described the world’s religions as many tributaries of the same river.

Perhaps my favourite session of all was on the role of nature in weird and Gothic literature. Authors Maggie Gee and Laura Jean McKay (both appearing via video link), and Ruth Padel, a New Networks stalwart, conversed with Bath Spa professor Richard Kerridge. Gee has been writing about climate change in her novels for nearly 40 years; she said the challenge is to make the language fresh again and connect with readers subliminally and emotionally, without preaching or lecturing. She called The Red Children, coming out in March, a future fairy tale, comic and hopeful, and read from the beginning, including a raven’s speech.

This connected with McKay’s The Animals in That Country, from which she read the passage where Jean realizes she can hear the lab mice talking to her. McKay said speculative fiction has been edging ever closer to reality in recent years; she recently realized she was reading Ling Ma’s zombie novel Severance as a guide to surviving the pandemic. In her opinion, novels are to open doors and ask questions – the opposite of what politicians do. Padel added that attention can be an antidote to eco-grief, with art a framework for creating resolution.

This connected with McKay’s The Animals in That Country, from which she read the passage where Jean realizes she can hear the lab mice talking to her. McKay said speculative fiction has been edging ever closer to reality in recent years; she recently realized she was reading Ling Ma’s zombie novel Severance as a guide to surviving the pandemic. In her opinion, novels are to open doors and ask questions – the opposite of what politicians do. Padel added that attention can be an antidote to eco-grief, with art a framework for creating resolution.

Longer sessions were punctuated with readings (from On Gallows Down and Samantha Walton’s Everybody Needs Beauty), performances (Merlyn Driver, who grew up without electricity and not going to school on Orkney, proposed the curlew album to the RSPB and played his song “Simmer Dim”) or short films – one on the plastic pollution encountered by a stand-up paddle boarder travelling the length of the Severn river and another on the regenerative farming a young couple are doing in Spain at Wild Finca.

Longer sessions were punctuated with readings (from On Gallows Down and Samantha Walton’s Everybody Needs Beauty), performances (Merlyn Driver, who grew up without electricity and not going to school on Orkney, proposed the curlew album to the RSPB and played his song “Simmer Dim”) or short films – one on the plastic pollution encountered by a stand-up paddle boarder travelling the length of the Severn river and another on the regenerative farming a young couple are doing in Spain at Wild Finca.

The closest we came to a debate over the weekend was with the final session on ecotourism. Representing the pro side was Ian Redmond, who works with mountain gorillas in Rwanda. The $1500 fee that each group of tourists pays to be taken into the reserve goes directly to conserving their habitat. But to get there people burn carbon flying long distances, and Nick Acheson finds that unconscionable. After 20 years as a wildlife guide to the amazing animals of Madagascar and South America, he’s vowed never to fly again. He stays close to home in Norfolk and travels by bike. His statistics were arresting and his argumentation hard to counter. Think hard about your motivation, he challenged. If you truly want to help local people and wildlife, donate money instead. The white saviour mentality is a danger here, too.

Much food for thought, then, though always in the back of the mind is the knowledge that (as some speakers did say aloud) this event preaches to the choir. How to reach those who haven’t fallen in love with the natural world, or haven’t woken up to the climate crisis? Those questions remain, but each year we have NNN to recharge the batteries.

Next time the conference will be back to York for the first weekend of November, with a tagline of “Survive, Thrive, Revive.” I’m looking forward to it already!