#1962Club: A Dozen Books I’d Read Before

I totally failed to read a new-to-me 1962 publication this year. I’m disappointed in myself as I usually manage to contribute one or two reviews to each of Karen and Simon’s year clubs, and it’s always a good excuse to read some classics.

My mistake this time was to only get one option: Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, which I had my husband borrow for me from the university library. I opened it up and couldn’t make head or tail of it. I’m sure it’s very clever and meta, and I’ve enjoyed Nabokov before (Pnin, in particular), but I clearly needed to be in the right frame of mind for a challenge, and this month I was not.

Looking through the Goodreads list of the top 100 books from 1962, and spying on others’ contributions to the week, though, I can see that it was a great year for literature (aren’t they all?). Here are 12 books from 1962 that I happen to have read before, most of which I’ve reviewed here in the past few years. I’ve linked to those and/or given review excerpts where I have them, and the rest I describe to the best of my muzzy memory.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats – A perennial favourite from my childhood, with a paper-collage style that has influenced many illustrators. Just looking at the cover makes me nostalgic for the sort of wintry American mornings when I’d open an eye to a curiously bright aura from around the window, glance at the clock and realize my mom had turned off my alarm because it was a snow day and I’d have nothing ahead of me apart from sledding, playing boardgames and drinking hot cocoa with my best friend. There was no better feeling.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

Here’s hoping I make a better effort at the next year club!

Love Your Library Begins: October 2021

It’s the opening month of my new Love Your Library meme! I hope some of you will join me in writing about the libraries you use and what you’ve borrowed from them recently. I plan to treat these monthly posts as a sort of miscellany.

Although I likely won’t do thorough Library Checkout rundowns anymore, I’ll show photos of what I’ve borrowed, give links to reviews of a few recent reads, and then feature something random, such as a reading theme or library policy or display.

Do share a link to your own post in the comments, and feel free to use the above image. I’m co-opting a hashtag that is already popular on Twitter and Instagram: #LoveYourLibrary.

Here’s a reminder of my ideas of what you might choose to post (this list will stay up on the project page):

- Photos or a list of your latest library book haul

- An account of a visit to a new-to-you library

- Full-length or mini reviews of some recent library reads

- A description of a particular feature of your local library

- A screenshot of the state of play of your online account

- An opinion piece about library policies (e.g. Covid procedures or fines amnesties)

- A write-up of a library event you attended, such as an author reading or book club.

If it’s related to libraries, I want to hear about it!

Recently borrowed

Stand-out reads

The Echo Chamber by John Boyne

John Boyne is such a literary chameleon. He’s been John Irving (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Patricia Highsmith (A Ladder to the Sky) and David Mitchell (A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom). Now, with this Internet-age state-of-the-nation satire featuring variously abhorrent characters, he’s channelling the likes of Jamie Attenberg, Jonathan Coe, Patricia Lockwood, Lionel Shriver and Emma Straub. Every member of the Cleverley family is a morally compromised fake. Boyne gives his characters amusing tics, and there are also some tremendously funny set pieces, such as Nelson’s speed dating escapade and George’s public outbursts. He links several storylines through the Ukrainian dancer Pylyp, who’s slept with almost every character in the book and has Beverley petsit for his tortoise.

John Boyne is such a literary chameleon. He’s been John Irving (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Patricia Highsmith (A Ladder to the Sky) and David Mitchell (A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom). Now, with this Internet-age state-of-the-nation satire featuring variously abhorrent characters, he’s channelling the likes of Jamie Attenberg, Jonathan Coe, Patricia Lockwood, Lionel Shriver and Emma Straub. Every member of the Cleverley family is a morally compromised fake. Boyne gives his characters amusing tics, and there are also some tremendously funny set pieces, such as Nelson’s speed dating escapade and George’s public outbursts. He links several storylines through the Ukrainian dancer Pylyp, who’s slept with almost every character in the book and has Beverley petsit for his tortoise.

What is Boyne spoofing here? Mostly smartphone addiction, but also cancel culture. I imagined George as Hugh Bonneville throughout; indeed, the novel would lend itself very well to screen adaptation. And I loved how Beverley’s new ghostwriter, never given any name beyond “the ghost,” feels like the most real and perceptive character of all. Surely one of the funniest books I will read this year. (Full review).

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

I was one of those rare readers who didn’t think so much of Normal People, so to me this felt like a return to form. Conversations with Friends was a surprise hit with me back in 2017 when I read it as part of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel the year she won. The themes here are much the same: friendship, nostalgia, sex, communication and the search for meaning. BWWAY is that little bit more existential: through the long-form e-mail correspondence between two friends from college, novelist Alice and literary magazine editor Eileen, we imbibe a lot of philosophizing about history, aesthetics and culture, and musings on the purpose of an individual life against the backdrop of the potential extinction of the species.

I was one of those rare readers who didn’t think so much of Normal People, so to me this felt like a return to form. Conversations with Friends was a surprise hit with me back in 2017 when I read it as part of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel the year she won. The themes here are much the same: friendship, nostalgia, sex, communication and the search for meaning. BWWAY is that little bit more existential: through the long-form e-mail correspondence between two friends from college, novelist Alice and literary magazine editor Eileen, we imbibe a lot of philosophizing about history, aesthetics and culture, and musings on the purpose of an individual life against the backdrop of the potential extinction of the species.

Through their relationships with Felix (a rough-around-the-edges warehouse worker) and Simon (slightly older and involved in politics), Rooney explores the question of whether lasting bonds can be formed despite perceived differences of class and intelligence. The background of Alice’s nervous breakdown and Simon’s Catholicism also bring in sensitive treatments of mental illness and faith. (Full review).

This month’s feature

I spotted a few of these during my volunteer shelving and then sought out a couple more. All five are picture books composed by authors not known for their writing for children.

Islandborn by Junot Díaz (illus. Leo Espinosa): “Every kid in Lola’s school was from somewhere else.” When the teacher asks them all to draw a picture of the country they came from, plucky Lola doesn’t know how to depict the Island. Since she left as a baby, she has to interview relatives and neighbours for their lasting impressions. For one man it’s mangoes so sweet they make you cry; for her grandmother it’s dolphins near the beach. She gathers the memories into a vibrant booklet. The 2D cut-paper style reminded me of Ezra Jack Keats.

Islandborn by Junot Díaz (illus. Leo Espinosa): “Every kid in Lola’s school was from somewhere else.” When the teacher asks them all to draw a picture of the country they came from, plucky Lola doesn’t know how to depict the Island. Since she left as a baby, she has to interview relatives and neighbours for their lasting impressions. For one man it’s mangoes so sweet they make you cry; for her grandmother it’s dolphins near the beach. She gathers the memories into a vibrant booklet. The 2D cut-paper style reminded me of Ezra Jack Keats.

The Islanders by Helen Dunmore (illus. Rebecca Cobb): Robbie and his family are back in Cornwall to visit Tamsin and her family. These two are the best of friends and explore along the beach together, creating their own little island by digging a channel and making a dam. As the week’s holiday comes toward an end, a magical night-time journey makes them wonder if their wish to make their island life their real life forever could come true. The brightly coloured paint and crayon illustrations are a little bit Charlie and Lola and very cute.

The Islanders by Helen Dunmore (illus. Rebecca Cobb): Robbie and his family are back in Cornwall to visit Tamsin and her family. These two are the best of friends and explore along the beach together, creating their own little island by digging a channel and making a dam. As the week’s holiday comes toward an end, a magical night-time journey makes them wonder if their wish to make their island life their real life forever could come true. The brightly coloured paint and crayon illustrations are a little bit Charlie and Lola and very cute.

Rose Blanche by Ian McEwan (illus. Roberto Innocenti): Patriotism is assumed for the title character and her mother as they cheer German soldiers heading off to war. There’s dramatic irony in Rose being our innocent witness to deprivations and abductions. One day she follows a truck out of town and past barriers and fences and stumbles onto a concentration camp. Seeing hungry children’s suffering, she starts bringing them food. Unfortunately, this gets pretty mawkish and, while I liked some of the tableau scenes – reminiscent of Brueghel or Stanley Spencer – the faces are awful. (Based on a story by Christophe Gallaz.)

Rose Blanche by Ian McEwan (illus. Roberto Innocenti): Patriotism is assumed for the title character and her mother as they cheer German soldiers heading off to war. There’s dramatic irony in Rose being our innocent witness to deprivations and abductions. One day she follows a truck out of town and past barriers and fences and stumbles onto a concentration camp. Seeing hungry children’s suffering, she starts bringing them food. Unfortunately, this gets pretty mawkish and, while I liked some of the tableau scenes – reminiscent of Brueghel or Stanley Spencer – the faces are awful. (Based on a story by Christophe Gallaz.)

Where Snow Angels Go by Maggie O’Farrell (illus. Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini): The snow angel Sylvie made last winter comes back to her to serve as her guardian angel, saving her from illness and accident risks. If you’re familiar with O’Farrell’s memoir I Am, I Am, I Am, this presents a similar catalogue of near-misses. For a picture book, it has a lot of words – several paragraphs’ worth on most of its 70 pages – so I imagine it’s more suitable for ages seven and up. I loved the fairy tale atmosphere, touches of humour, and drawing style.

Where Snow Angels Go by Maggie O’Farrell (illus. Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini): The snow angel Sylvie made last winter comes back to her to serve as her guardian angel, saving her from illness and accident risks. If you’re familiar with O’Farrell’s memoir I Am, I Am, I Am, this presents a similar catalogue of near-misses. For a picture book, it has a lot of words – several paragraphs’ worth on most of its 70 pages – so I imagine it’s more suitable for ages seven and up. I loved the fairy tale atmosphere, touches of humour, and drawing style.

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird (illus. Magenta Fox): Kit’s birthday present is Maud, a guinea pig in a judo uniform. None of the other household pets – Derrick the cockatoo, Dora the cat, and Bob the pug – know what to make of her. Like in The Secret Life of Pets, the pets take over, interacting while everyone’s out at school and work. At first Maud tries making herself like the others, but after she spends an afternoon with an eccentric neighbour she realizes all she needs to be is herself. It’s not the first time married couple Smith and Laird have published an in-joke (their 2018 releases – an essay collection and a book of poems, respectively – are both entitled Feel Free): Kit is their daughter’s name and Maud is their pug’s. But this was cute enough to let them off.

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird (illus. Magenta Fox): Kit’s birthday present is Maud, a guinea pig in a judo uniform. None of the other household pets – Derrick the cockatoo, Dora the cat, and Bob the pug – know what to make of her. Like in The Secret Life of Pets, the pets take over, interacting while everyone’s out at school and work. At first Maud tries making herself like the others, but after she spends an afternoon with an eccentric neighbour she realizes all she needs to be is herself. It’s not the first time married couple Smith and Laird have published an in-joke (their 2018 releases – an essay collection and a book of poems, respectively – are both entitled Feel Free): Kit is their daughter’s name and Maud is their pug’s. But this was cute enough to let them off.

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest)

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest) I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf.

I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf. The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)

The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)  The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)

The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)  This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

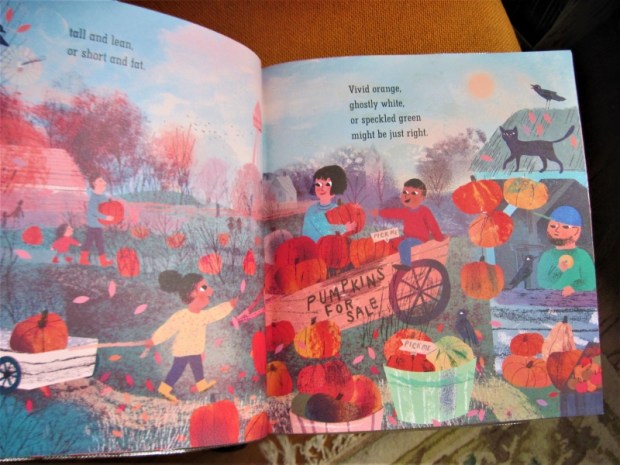

This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections. From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)  Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?

Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?