Two “Summer” Reads: Knausgaard and Trevor

Last year at about this time I reviewed Jonathan Smith’s Summer in February and Elizabeth Taylor’s In a Summer Season, two charming English novels about how love can upend ordinary life. This month I read my first William Trevor novel, Love and Summer, which is very much in that vein. My other selection, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s last of four seasonal installments written for his young daughter, is a mostly nonfiction hybrid.

Summer by Karl Ove Knausgaard (2016; English translation, 2018)

Illustrated by German artist Anselm Kiefer.

I’ve now read three volumes from the Seasons Quartet – all but Spring. The series started with Knausgaard addressing his fourth child in utero. By now she’s two years old but still the recipient of his nostalgic, slightly didactic essays on seasonal topics, as well as the “you” some of his journal entries are written to. I wasn’t so keen on Autumn, but Winter and Summer are both brilliant for how they move from tangibles – ice cream cones, camping, fruit flies, seagulls, butterflies and the circus – into abstract notions of thought, memory, identity and meaning. That fluidity is especially notable here when Knausgaard drifts in and out of the imagined experience of an elderly woman of his grandfather’s acquaintance who fell in love with an Austrian soldier and abandoned her children during World War II.

I especially enjoyed two stories: traveling with his son to Brazil for a literary festival where he ran into English surgeon Henry Marsh, and fainting at an overcrowded publisher party in London. He’s always highly aware of himself (he never gives open-mouthed smiles because of his awful teeth) and of others (this woman at the party is desperate to appear young). But more so than these stand-out events and his memories of childhood, he gives pride of place to everyday life, things like chauffeuring his three older children to their various activities and shopping at the supermarket for barbecue food. “By writing it I reveal that not only do I think about it, I attach importance to it. … I love repetition. Repetitions turn time into a place, turn the days into a house.” I highlighted dozens of passages in the Kindle book. I’ll need to catch up on Spring, and then perhaps return to the My Struggle books; I only ever read the first.

My rating:

Love and Summer by William Trevor (2009)

Trevor (1928–2016) was considered a writer’s writer and a critic’s dream for the simple profundity of his prose. I had long meant to try his work. This short novel is set over the course of one summer in a small Irish town in the 1950s, and opens on the day of the funeral of old Mrs. Connulty. A stranger is seen taking photographs around town, and there is much murmuring about who he might be. He is Florian Kilderry, who recently inherited his Anglo-Italian artist parents’ crumbling country house. It’s impossible to pay the debts and keep the house going, so he plans to sell it and its contents as soon as possible and move abroad, perhaps to Scandinavia.

Trevor (1928–2016) was considered a writer’s writer and a critic’s dream for the simple profundity of his prose. I had long meant to try his work. This short novel is set over the course of one summer in a small Irish town in the 1950s, and opens on the day of the funeral of old Mrs. Connulty. A stranger is seen taking photographs around town, and there is much murmuring about who he might be. He is Florian Kilderry, who recently inherited his Anglo-Italian artist parents’ crumbling country house. It’s impossible to pay the debts and keep the house going, so he plans to sell it and its contents as soon as possible and move abroad, perhaps to Scandinavia.

But he hasn’t passed through Rathmoye without leaving ripples. Ellie Dillahan, a young farmer’s wife who was raised by nuns and initially moved to Dillahan’s as his housekeeper, falls in love with the stranger almost before she meets him, and they embark on a short-lived liaison. Blink and you’ll miss that the relationship is actually sexual; Trevor only uses the word “embraced” twice, I think. That reticence keeps it from being a torrid affair, yet we do get a sense of how wrenching the thought of Florian leaving becomes for Ellie. Trevor often moves from descriptions of nature or farm chores straight into Ellie’s thoughts, or vice versa.

“In the crab-apple orchard she scattered grain and the hens came rushing to her. She hadn’t been aware that she didn’t love her husband. Love hadn’t come into it”

“He [Florian] would be gone, as the dead are gone, and that would be there all day, in the kitchen and in the yard, when she brought in anthracite for the Rayburn, when she scalded the churns, while she fed the hens and stacked the turf.”

This is quietly beautiful writing – perhaps too quiet for me, despite the quirky secondary characters around the town (including the busybody Connulty daughter and the madman Orpen Wren) – but I would recommend Trevor to readers of Mary Costello and Colm Tóibín. I would also like to try Trevor’s short stories, for which he was particularly known; I think in small doses his subtle relationship studies and gentle writing would truly shine.

My rating:

Summery reading options for next year: The Heat of the Day by Elizabeth Bowen, One Summer: America, 1927 by Bill Bryson, and The Go-Between by L. P. Hartley (set over a long, hot summer). I may also get Sunburn by Laura Lippman and Heat Wave by Penelope Lively out from the library.

Have you read any “Summer” books lately?

20 Books of Summer, #5–8: Anderson, Cusk, Fitch & L’Engle

I’ve been reading a feminist memoir set on Cape Cod, a subtle novel about the inner life and outward experiences of a writer, a soapy literary thriller about a troubled mother and teen daughter, and a slightly melancholy reminiscence of an aged mother succumbing to dementia.

A Walk on the Beach: Tales of Wisdom from an Unconventional Woman by Joan Anderson (2004)

This is the third volume in a loose autobiographical trilogy about Anderson’s experiment with taking a break from her marriage and living alone in a Cape Cod cottage to figure out what she really wanted from the rest of her life. Specifically, this book is about the inspirational relationship she formed with Joan Erikson, who moved to the area in her eighties when her husband, the famous psychologist Erik Erikson, was admitted to a care home. Joanie was a thinker and author in her own right, publishing books on life’s stages, especially those of older age. She encouraged Anderson to have the confidence to write her own story, and to take up challenges like a trip to Peru and learning to weave on a loom. Joanie’s aphoristic advice is valuable, but there’s a fair bit of overlap between this book and A Year by the Sea, which I would recommend over this.

This is the third volume in a loose autobiographical trilogy about Anderson’s experiment with taking a break from her marriage and living alone in a Cape Cod cottage to figure out what she really wanted from the rest of her life. Specifically, this book is about the inspirational relationship she formed with Joan Erikson, who moved to the area in her eighties when her husband, the famous psychologist Erik Erikson, was admitted to a care home. Joanie was a thinker and author in her own right, publishing books on life’s stages, especially those of older age. She encouraged Anderson to have the confidence to write her own story, and to take up challenges like a trip to Peru and learning to weave on a loom. Joanie’s aphoristic advice is valuable, but there’s a fair bit of overlap between this book and A Year by the Sea, which I would recommend over this.

My rating:

Some of Joan Erikson’s words of wisdom:

“Doing something with your hands, rather than your head, is often the best route to clarity.”

“wisdom comes from life’s experiences well digested. Stop relying so much on your mind and get in touch with experience.”

“The struggle is to try and obtain a sense of participation in your life the whole way through. We must treasure old age, but not wallow in nostalgia.”

Transit by Rachel Cusk (2016)

I finally made it through a Rachel Cusk book! (This was my third attempt; I made it just a few pages into Aftermath and 60 pages through Outline.) I suspected this would make a good plane read, and thankfully I was right. Each chapter is a perfectly formed short story, a snapshot of one aspect of Faye’s life and the relationships that have shaped her: a former lover she bumps into in London, a builder who tells her the flat she’s bought is a lost cause, the awful downstairs neighbors who hate her with a passion, the fellow writers (based on Edmund White and Karl Ove Knausgaard?) at a literary festival event who hog most of the time, the jolly Eastern European construction workers who undertake her renovations, a childless friend who works in fashion design, and a country cousin who’s struggling with his new blended family.

I finally made it through a Rachel Cusk book! (This was my third attempt; I made it just a few pages into Aftermath and 60 pages through Outline.) I suspected this would make a good plane read, and thankfully I was right. Each chapter is a perfectly formed short story, a snapshot of one aspect of Faye’s life and the relationships that have shaped her: a former lover she bumps into in London, a builder who tells her the flat she’s bought is a lost cause, the awful downstairs neighbors who hate her with a passion, the fellow writers (based on Edmund White and Karl Ove Knausgaard?) at a literary festival event who hog most of the time, the jolly Eastern European construction workers who undertake her renovations, a childless friend who works in fashion design, and a country cousin who’s struggling with his new blended family.

Like in Outline, the novel is based largely on the conversations Faye overhears or participates in (“I had found out more, I said, by listening than I had ever thought possible”), but I sensed more of her personality this time, and could relate to her questioning: Why do her neighbors hate her so? How much of her life is fated, and how much has she chosen? I doubt I’ll read another book by Cusk, but I ended up surprisingly grateful to have gotten hold of this one as a free proof copy of the new paperback edition from the Faber Spring Party.

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

“we examine least what has formed us the most, and instead find ourselves driven blindly to re-enact it.”

“Without children or partner, without meaningful family or a home, a day can last an eternity: a life without those things is a life without a story, a life in which there is nothing – no narrative flights, no plot developments, no immersive human dramas – to alleviate the cruelly meticulous passing of time.”

White Oleander by Janet Fitch (1999)

Man, that Oprah knows how to pick ’em! This was a terrific read; I’m not sure why I’d never gotten to it before. I read huge chunks during my travel to the States and then slowed down quite a bit, which was a shame because it meant I felt less connected to Astrid’s later struggles in the foster care system. It’s an atmospheric novel full of oppressive Los Angeles heat and a classic noir flavor that shades into gritty realism as it goes on, taking us from when Astrid is 12 to when she’s a young woman out in the world on her own.

Man, that Oprah knows how to pick ’em! This was a terrific read; I’m not sure why I’d never gotten to it before. I read huge chunks during my travel to the States and then slowed down quite a bit, which was a shame because it meant I felt less connected to Astrid’s later struggles in the foster care system. It’s an atmospheric novel full of oppressive Los Angeles heat and a classic noir flavor that shades into gritty realism as it goes on, taking us from when Astrid is 12 to when she’s a young woman out in the world on her own.

Astrid’s mother Ingrid, an elitist poet, becomes obsessed with a lover who spurned her and goes to jail for his murder. Bouncing between foster homes and children’s institutions, Astrid is plunged into a world of sex, drugs, violence and short-lived piety. “Like a limpet I attached to anything, anyone who showed me the least attention,” she writes. Her role models change over the years, but always in the background is the icy influence of her mother, through letters and visits.

Fitch’s writing is sumptuous, as in a house “the color of a tropical lagoon on a postcard thirty years out of date, a Gauguin syphilitic nightmare.” I might have liked a tiny bit more of Ingrid in the book, but I can still recommend this one wholeheartedly as summer reading.

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

The knock-out opening two lines: “The Santa Anas blew in hot from the desert, shriveling the last of the spring grass into whiskers of pale straw. Only the oleanders thrived, their delicate poisonous blossoms, their dagger green leaves.”

“I couldn’t imagine my mother in prison. She didn’t smoke or chew on toothpicks. She didn’t say ‘bitch’ or ‘fuck.’ She spoke four languages, quoted T. S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas, drank Lapsang souchong out of a porcelain cup. She had never been inside a McDonald’s. She had lived in Paris and Amsterdam. Freiburg and Martinique. How could she be in prison?”

The Summer of the Great-Grandmother by Madeleine L’Engle (1974)

L’Engle is better known for children’s books, but wrote tons for adults, too. In this second volume of The Crosswicks Journal, she recounts her family history as a way of remembering on behalf of her mother, who at age 90 was slipping into dementia in her final summer. “I talked awhile, earlier this summer, about wanting my mother to have a dignified death. But there is nothing dignified about incontinence and senility.” L’Engle found herself in the unwanted position of being like her mother’s mother, and had to accept that she had no control over the situation. “This summer is practice in dying for me as well as for my mother.”

L’Engle is better known for children’s books, but wrote tons for adults, too. In this second volume of The Crosswicks Journal, she recounts her family history as a way of remembering on behalf of her mother, who at age 90 was slipping into dementia in her final summer. “I talked awhile, earlier this summer, about wanting my mother to have a dignified death. But there is nothing dignified about incontinence and senility.” L’Engle found herself in the unwanted position of being like her mother’s mother, and had to accept that she had no control over the situation. “This summer is practice in dying for me as well as for my mother.”

One of the reasons L’Engle was driven to write science fiction was because she couldn’t reconcile the idea of permanent human extinction with her Christian faith, but nor could she honestly affirm every word of the Creed. Hers is a more broad-minded, mystical spirituality that really appeals to me. (Her early life reminds me of May Sarton’s, as recounted in I Knew a Phoenix: both were born right around World War I, raised partially in Europe and sent to boarding school; a frequent theme in their nonfiction is the regenerative power of solitude and of the writing process itself.)

My rating:

Some favorite lines:

“I said [in a lecture] that the artist’s response to the irrationality of the world is to paint or sing or write, not to impose restrictive rules but to rejoice in pattern and meaning, for there is something in all artists which rejects coincidence and accident. And I went on to say that we must meet the precariousness of the universe without self-pity, and with dignity and courage.”

“Our lives are given a certain dignity by their very evanescence. If there were never to be an end to my quiet moments at the brook, if I could sit on the rock forever, I would not treasure these minutes so much. If our associations with the people we love were to have no termination, we would not value them as much as we do.”

20 Books of Summer #4 + Substitutes & Plane Reading

You’ll have to excuse me posting twice in one day. I’ve just finished packing the last few things for my three weeks in America, and want to get my latest #20BooksofSummer review out there before I fly early tomorrow. What with a layover in Toronto, it will be a very long day of travel, so I think the volume of reading material I’m taking is justified! (See the last photo of the post.)

Four Wings and a Prayer: Caught in the Mystery of the Monarch Butterfly by Sue Halpern (2001)

I admire nonfiction books that successfully combine lots of genres into a dynamic narrative. This one incorporates travel, science, memoir, history, and even politics. Halpern spent a year tracking monarch butterflies on their biannual continent-wide migrations, which were still not well understood at that point. She rides through Texas into Mexico with Bill Calvert, field researcher extraordinaire; goes gliding with David Gibo, a university biologist, in fields near Toronto; and hears from scientists and laymen alike about the monarchs’ habits and outlook. It happened to be a worryingly poor year for the butterflies, yet citizen science initiatives provided valuable information that could be used to predict their future.

I admire nonfiction books that successfully combine lots of genres into a dynamic narrative. This one incorporates travel, science, memoir, history, and even politics. Halpern spent a year tracking monarch butterflies on their biannual continent-wide migrations, which were still not well understood at that point. She rides through Texas into Mexico with Bill Calvert, field researcher extraordinaire; goes gliding with David Gibo, a university biologist, in fields near Toronto; and hears from scientists and laymen alike about the monarchs’ habits and outlook. It happened to be a worryingly poor year for the butterflies, yet citizen science initiatives provided valuable information that could be used to predict their future.

The book is especially insightful about clashes between environmentalist initiatives and local livelihoods in Mexico (tree huggers versus subsistence loggers) and the joy of doing practical science with simple tools you make yourself. It’s also about how focused attention becomes passion. “Science, like belief, starts with wonder, and wonder starts with a question,” Halpern writes.

The style is engaging, though at nearly 20 years old the book feels a bit dated, and I might have liked more personal reflections than interviews with (middle-aged, white, male) scientists. I only realized on the very last page, through the acknowledgments, that the author is married to Bill McKibben, a respected environment writer. [She frequently mentions Fred Urquhart, a Toronto zoology professor; I wondered if he could be related to Jane Urquhart, a Canadian novelist whose novel Sanctuary Line features monarchs. (Turns out: no relation. Oh well!)]

Readalikes: Farther Away by Jonathan Franzen & Ruins by Peter Kuper

My rating:

I’ve already done some substituting on my 20 Books of Summer. I decided against reading Vendela Vida’s Girls on the Verge after perusing the table of contents and the first few pages and gauging reader opinions on Goodreads. I have a couple of review books, Twister by Genanne Walsh and The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr, that I’m enjoying but will have to leave behind while I’m in the States, so I may need that little extra push to finish them once I get back. I’ve also been rereading a favorite, Paulette Bates Alden’s memoir Crossing the Moon, which has proved an excellent follow-up to Sheila Heti’s Motherhood.

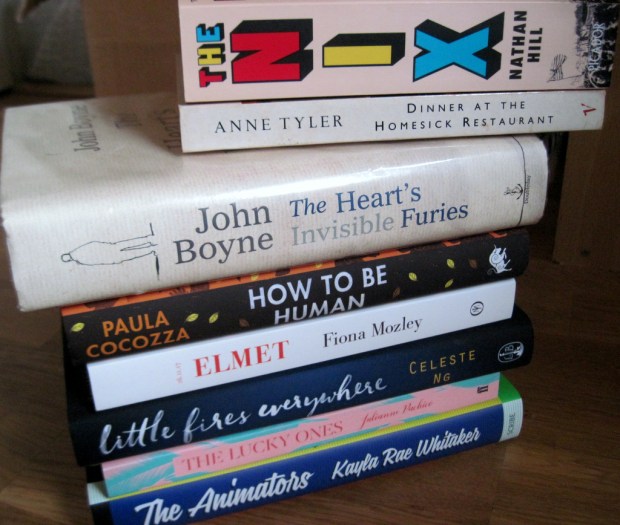

(What I haven’t determined yet is which books these will be standing in for.) Waiting in the wings in case further substitutions are needed is this stack of review books:

Also from the #20Books list and coming with me on the flight are Madeleine L’Engle’s The Summer of the Great-Grandmother and Janet Fitch’s White Oleander, which are both terrific thus far. The final print book joining me for the journey is Transit by Rachel Cusk. I have attempted to read her twice before and failed to get through a whole book, so we’ll see if it’s third time lucky. It seems like the perfect book to read in transit to Canada, after all.

Finally, in progress on the Kindle are Summer by Karl Ove Knausgaard, the last in his set of four seasonal essay collections, and The Late Bloomers’ Club by Louise Miller, another cozy novel set in fictional Guthrie, Vermont, which she introduced in her previous book, The City Baker’s Guide to Country Living.

It’ll be a busy few weeks helping my parents pack up their house and moving my mom into her new place, plus doing a reduced freelance work load for the final two weeks. It’s also going to be a strange time because I have to say goodbye to a house that’s been a part of my life for 13 years, and sort through box after box of mementoes before putting everything into medium-term storage.

I won’t be online all that much, and can’t promise to keep up with everyone else’s blogs, but I’ll try to pop in with a few reviews.

Happy July reading!

December Reading Plans & Year-End Goals

Somehow the end of the year is less than four weeks away, so it’s time to start getting realistic about what I can read before 2018 begins. I wish I was the sort of person who was always reading books 4+ months before the release date and setting trends, but I’ve only read three 2018 releases so far, and it’s doubtful I’ll get to more than another handful before the end of the year. Any that I do read and can recommend I will round up briefly in a couple weeks or so.

I’m at least feeling pleased with myself for resuming and/or finishing all but two of the 14 books I had on hold as of last month; one I finally DNFed (The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen) and another I’m happy to put off until the new year (Paradise Road: Jack Kerouac’s Lost Highway and My Search for America by Jay Atkinson – since he’s recreating the journey taken for On the Road, I should look over a copy of that first). Ideally, the plan is to finish all the books I’m currently reading to clear the decks for a new year.

Some other vague reading plans for the month:

I might do a Classic of the Month (I’m currently reading The Awakening by Kate Chopin) … but a Doorstopper isn’t looking likely unless I pick up Hillary Clinton’s Living History. However, there are a few books of doorstopper length pictured in the piles below.

Christmas-themed books. The title-less book with the ribbon is Seven Days of Us by Francesca Hornak, a Goodreads giveaway win. I think I’ll start that plus the Amory today since I’m going to a carol service this evening. On Kindle: A Very Russian Christmas, a story anthology I read about half of last year and might finish this year.

Winter-themed books. On Kindle: currently reading When the Professor Got Stuck in the Snow by Dan Rhodes; Winter by Karl Ove Knausgaard is to be read. (The subtitle of Spufford’s book is “Ice and the English Imagination”.)

As the holidays approach, I start to daydream about what books I might indulge in during the time off. (I’m giving myself 11 whole days off of editing, though I may still have a few paid reviews to squeeze in.) The kinds of books I would like to prioritize are:

Absorbing reads. Books that promise to be thrilling (says the person who doesn’t generally read crime thrillers); books I can get lost in (often long ones). On Kindle: The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden.

Cozy reads. Animal books, especially cat books, generally fall into this category, as do funny books and children’s books. My mother and I love Braun’s cat mysteries; I read them all starting when I was about 11. I’ve never reread any, so I’d like to see how they stand up years later. Goodreads has been trying to recommend me Duncton Wood for ages, which is funny as I’ve had my eye on it anyway. My husband read the series when he was a kid and we still own some well-worn copies. Given how much I loved Watership Down and Brian Jacques’ novels as a child, I’m hoping it’s a pretty safe bet.

Books I’ve been meaning to read for ages. ’Nuff said. On Kindle: far too many.

And, as always, I’m in the position of wishing I’d gotten to many more of this year’s releases. In fact, there are at least 22 books from 2017 on my e-readers that I still intend to read:

- A Precautionary Tale: How One Small Town Banned Pesticides, Preserved Its Food Heritage, and Inspired a Movement by Philip Ackerman-Leist

- In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

The Floating World by C. Morgan Babst

The Floating World by C. Morgan Babst- The Day that Went Missing by Richard Beard

- The Best American Series taster volume (skim only?)

- The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne*

- Guesswork: A Memoir in Essays by Martha Cooley

- The Night Brother by Rosie Garland

- Difficult Women by Roxane Gay

- The Twelve-Mile Straight by Eleanor Henderson

- Eco-Dementia by Janet Kauffman [poetry]

- The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy

- A Stitch of Time: The Year a Brain Injury Changed My Language and Life by Lauren Marks

- Hug Everyone You Know: A Year of Community, Courage, and Cancer by Antoinette Truglio Martin

Homing Instinct: Early Motherhood on a Midwestern Farm by Sarah Menkedick

Homing Instinct: Early Motherhood on a Midwestern Farm by Sarah Menkedick- One Station Away by Olaf Olafsson

- Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone by Richard Lloyd Parry

- Memory’s Last Breath: Field Notes on My Dementia by Gerda Saunders

- See What I Have Done by Sarah Schmidt

- What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories by Laura Shapiro

- Midnight at the Bright Ideas Bookstore by Matthew J. Sullivan

- Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward*

* = The two I most want to read, and thus will try hardest to get to before the end of the year. But the Boyne sure is long.

[The 2017 book I most wanted to read but never got hold of in any form was The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas.]

Are there any books from my stacks or lists that you want to put in a good word for?

How does December’s reading look for you?

Library Checkout Reboot

The Library Checkout blog meme was created by Shannon of River City Reading and previously hosted by Charleen of It’s a Portable Magic. I’m taking over as the host as of this month. There’s nothing too complicated about this challenge; it’s just a way of celebrating the libraries that you frequent, whether that’s your local public library branch or another specialist library. Maybe keeping track of your borrowing habits will encourage you to make even more use of libraries. Use ’em or lose ’em, after all.

I usually post this on the last Monday of the month, but you can post whenever is convenient for you. I’ll look into a proper link-up service, but for now just paste a link to your own post in the comments. (Feel free to use the above image, too.) The basic categories are: Library Books Read; Currently Reading; Checked Out, To Be Read; On Hold; and Returned Unread. Others I sometimes add are Skimmed Only and Returned Unfinished. I generally add in star ratings and links to reviews of any books I’ve managed to read.

A couple of weeks ago I went nuts at the university library on my husband’s campus. As a staff member he can borrow 25 books pretty much indefinitely (unless they’re requested). One or both of us has been associated with the University of Reading for over 15 years now, so the library there is a nostalgic place I love visiting. It’s technically currently undergoing a major renovation, but the books are still available, so it doesn’t make much difference to me.

LIBRARY BOOKS READ

- Interlibrary Loan Sharks and Seedy Roms: Cartoons from Libraryland by Benita L. Epstein

(So dated, I’m afraid! A few good ones, though.)

(So dated, I’m afraid! A few good ones, though.) - Fall Down 7 Times, Get Up 8 by Naoki Higashida

- Autumn by Karl Ove Knausgaard

- A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [university library]

SKIMMED ONLY

- Option B by Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant

CURRENTLY READING

- Slade House by David Mitchell

- Halfway to Silence by May Sarton [poetry; university library]

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

A manageable selection from the public library:

Plus loads of books from lots of different genres from the university library; these will keep me going well past Christmas, I reckon!

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Seventh Function of Language by Laurent Binet

Have you been taking advantage of your local libraries? What appeals from my library stacks?

Library Checkout: September 2017

I’ve mostly been reading review copies, books from my own shelves, and Kindle books this month, though I did manage one library read during our trip to Amsterdam. While I was at the public library on Thursday, however, I was tempted by several titles from the bestsellers display – these are two-week loans with no renewals, so I have to devote some serious time to them this week and into early October. I’ve read and enjoyed one previous book each by Binet, Knausgaard and Higashida (I just realized those are all translated – how about that? Usually I have to urge myself to remember to read literature in translation!), so will be interested to see how their most recent work stacks up.

LIBRARY BOOKS READ

- Tulip Fever by Deborah Moggach

CURRENTLY READING

- The Seventh Function of Language by Laurent Binet

- Autumn by Karl Ove Knausgaard

- A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [from university library]

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Fall Down 7 Times, Get Up 8, Naoki Higashida

(Hosted by Charleen of It’s a Portable Magic.)

Have you been taking advantage of your local libraries? What appeals from my list?

Four Recommended June Releases

Here are four enjoyable books due out next month that I was lucky enough to read in advance. The first is the sophomore novel from an author whose work I’ve enjoyed before, the second is a highly anticipated memoir from an author new to me, and the third and fourth – both among my favorite books of 2017 so far – strike me as 2018 Wellcome Book Prize hopefuls: one is a highly autobiographical novel about bereavement, and the other is a courageous memoir about facing terminal cancer. I’ve pulled 250-word extracts from my full reviews and hope you’ll be tempted by one or more of these.

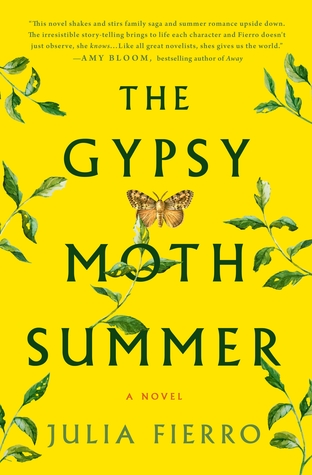

The Gypsy Moth Summer by Julia Fierro

(Coming from St. Martin’s Press on June 6th)

It’s the summer of 1992 and a plague of gypsy moth caterpillars has hit Avalon Island, a community built around Grudder Aviation. The creatures are just one of many threats to this would-be fairy tale world. For Maddie Pencott LaRosa, it’s no simple Sweet Sixteen time of testing out drugs and sex at parties. Her grandfather, Grudder’s president, is back in town with her grandmother, Veronica, and they’re eager to hide the fact that he’s losing his marbles. Also recently returned is Leslie Day Marshall, daughter of the previous Grudder president; she’s inherited “The Castle” and shocked everyone with the family she brought back: Jules, an African-American landscape architect, and their two mixed-race children.

It’s the summer of 1992 and a plague of gypsy moth caterpillars has hit Avalon Island, a community built around Grudder Aviation. The creatures are just one of many threats to this would-be fairy tale world. For Maddie Pencott LaRosa, it’s no simple Sweet Sixteen time of testing out drugs and sex at parties. Her grandfather, Grudder’s president, is back in town with her grandmother, Veronica, and they’re eager to hide the fact that he’s losing his marbles. Also recently returned is Leslie Day Marshall, daughter of the previous Grudder president; she’s inherited “The Castle” and shocked everyone with the family she brought back: Jules, an African-American landscape architect, and their two mixed-race children.

Depending on when you were born, you might not think of the 1990s as “history,” but this novel does what the best historical fiction does: expertly evoke a time period. Moving between the perspectives of six major characters, the novel captures all the promise and peril of life, especially for those who love the ‘wrong’ people. I especially loved small meetings of worlds, like Maddie and Veronica getting together for tea and Oprah.

My main criticism would be that there is a lot going on here – racism, domestic violence, alcohol and prescription drug abuse, cancer, teen sex (a whole lotta sex in general) – and that can make things feel melodramatic. But in general I loved the atmosphere: a sultry summer of Gatsby-esque glittering parties and garden mazes, a time dripping with secrets, sex and caterpillar poop.

[It felt like I kept seeing references to gypsy moths in the run-up to reading this book, like a passage from Amy Poehler’s Yes Please, and a random secondhand book I spotted in Hay-on-Wye (though in that case it’s actually the name of a ship and is a record of a sea voyage).]

Read-alike: The Seed Collectors by Scarlett Thomas

My rating:

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body by Roxane Gay

(Coming from HarperCollins on June 13th [USA] and from Corsair on August 3rd [UK])

I’d never read anything by Roxane Gay before, but somehow already knew the basics of her story: the daughter of Haitian immigrants to the American Midwest, she was gang raped at age 12, and to some extent everything she’s done and become since then has been influenced by that one horrific experience. Not least her compulsive overeating: “I ate and ate and ate to build my body into a fortress,”she writes. At her heaviest Gay was super morbidly obese according to her BMI, a term that “frames fat people like we are the walking dead.”

I’d never read anything by Roxane Gay before, but somehow already knew the basics of her story: the daughter of Haitian immigrants to the American Midwest, she was gang raped at age 12, and to some extent everything she’s done and become since then has been influenced by that one horrific experience. Not least her compulsive overeating: “I ate and ate and ate to build my body into a fortress,”she writes. At her heaviest Gay was super morbidly obese according to her BMI, a term that “frames fat people like we are the walking dead.”

Though presented as a memoir, this is more like a collection of short autobiographical essays (88 of them, in six sections). The portions that could together be dubbed her life story take up about a third of the book, and the rest is riffs around a cluster of related topics: weight, diet, exercise and body image. The writing style is matter-of-fact (e.g. “My body is a cage of my own making”), which means she never comes across as self-pitying. I appreciate how she holds opposing notions in tension: she doesn’t know how she developed such an “unruly” body; she knows exactly how it happened.

The structure of the book made it a little repetitive for me, but I think what Gay has written will be of tremendous value, not just to rape victims or those whose BMI is classed as obese, but to anyone who has struggled with body image – so pretty much everyone, especially women.

Read-alike: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

My rating:

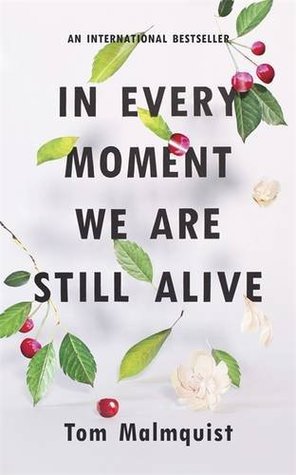

In Every Moment We Are Still Alive by Tom Malmquist

(Coming on from Sceptre on June 1st [UK] and from Melville House on February 6, 2018 [USA])

In this autobiographical novel from a Swedish poet, Tom faces the loss of his partner and his father in quick succession. The novel opens in medias res at Söder hospital, where Tom’s long-time girlfriend, Karin, has been rushed for breathing problems. Doctors initially suspect pneumonia or a blood clot, but a huge increase in her white blood cells confirms leukemia. This might seem manageable if it weren’t for Karin, 33, being pregnant with their first child. The next morning she’s transferred to another hospital for a Cesarean section and, before he can catch his breath, Tom is effectively a single parent to Livia, delivered six weeks early.

In this autobiographical novel from a Swedish poet, Tom faces the loss of his partner and his father in quick succession. The novel opens in medias res at Söder hospital, where Tom’s long-time girlfriend, Karin, has been rushed for breathing problems. Doctors initially suspect pneumonia or a blood clot, but a huge increase in her white blood cells confirms leukemia. This might seem manageable if it weren’t for Karin, 33, being pregnant with their first child. The next morning she’s transferred to another hospital for a Cesarean section and, before he can catch his breath, Tom is effectively a single parent to Livia, delivered six weeks early.

Malmquist does an extraordinary job of depicting Tom’s bewilderment. He records word for word what busy doctors and jobsworth nurses have to say, but because there are no speech marks their monologues merge with Tom’s thoughts, conversations and descriptions of the disorienting hospital atmosphere to produce a seamless narrative of frightened confusion. There is an especially effective contrast set up between Karin’s frantic emergency room treatment and the peaceful neonatal ward where Livia is being cared for.

While it’s being marketed as a novel, this reads more like a stylized memoir. Similar to Karl Ove Knausgaard’s books, it features the author as the central character and narrator, and the story of grief it tells is a highly personal one.With its frank look at medical crises, this is a book I fully expect to see on next year’s Wellcome Book Prize shortlist.

Read-alike: Mend the Living by Maylis de Kerangal

My rating:

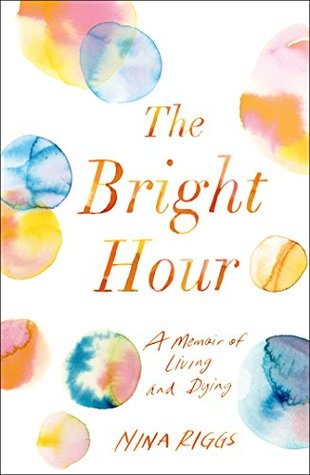

The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs

(Coming on June 6th from Simon & Schuster [USA] and from Text Publishing on August 3rd [UK])

You’re going to hear a lot about this one. It’s been likened to When Breath Becomes Air, an apt comparison given the beauty of the prose and the literary and philosophical approach to terminal cancer. It’s a wonderful book, so wry and honest, with a voice that reminds me of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth McCracken.

You’re going to hear a lot about this one. It’s been likened to When Breath Becomes Air, an apt comparison given the beauty of the prose and the literary and philosophical approach to terminal cancer. It’s a wonderful book, so wry and honest, with a voice that reminds me of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth McCracken.

It started with a tiny spot of cancer in the breast. “No one dies from one small spot,” Nina Riggs and her husband told themselves. Until it wasn’t just a spot but a larger tumor that required a mastectomy. And then there was the severe back pain that alerted them to metastases in her spine, and later in her lungs. Riggs was a great-great-great-granddaughter of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and she quotes from her ancestor’s essays as well as from Michel de Montaigne’s philosophy of life to put things in perspective.

Riggs started out as a poet, and you can tell. She’s an expert at capturing the moments that make life alternately euphoric and unbearable – sometimes both at once. Usually these moments are experienced with family: her tough mother, who died after nine years with multiple myeloma, providing her with a kind of “morbid test drive” for her own death; and her husband and their two precocious sons. Whether she’s choosing an expensive couch, bringing home a puppy, or surprising her sons with a trip to Universal Studios, she’s always engaged in life. You never get a sense of resignation or despair.

Some of my favorite lines:

“inside the MRI machine, where it sounded like hostile aliens had formed a punk band”

“my pubic hair all falls out at once in the shower and shows up like a drowned muskrat in the drain.”

“My wig smells toxic and makes me feel like a bank robber. But maybe it is just a cloak for riding out into suspicious country.”

“‘Merry Christmas,’ says a nurse who is measuring my urine into a jug in the bathroom. ‘Do you want some pain meds? Do you want another stool softener?’”

(Nina Riggs died at age 39 on February 23, 2017.)

Read-alike: A Series of Catastrophes and Miracles by Mary Elizabeth Williams

My rating:

In this second book of the Farthing Wood series, the animals endure a harsh winter in their new home, the White Deer Park. When Badger falls down a slope and injures his leg, he’s nursed back to health at the Warden’s cottage, where Ginger Cat tempts him to join in a life of comfort and plenty. Meanwhile, Fox, Tawny Owl and the others are near starvation, and resort to leaving the park and stealing food from farms and rubbish bins. They have to band together and use their cunning to survive. This was a sweet book that reminded me of my childhood love of anthropomorphized animal stories (like Watership Down and the Redwall series). I doubt I’ll read another from the series, but this was a quaint read for the season.

In this second book of the Farthing Wood series, the animals endure a harsh winter in their new home, the White Deer Park. When Badger falls down a slope and injures his leg, he’s nursed back to health at the Warden’s cottage, where Ginger Cat tempts him to join in a life of comfort and plenty. Meanwhile, Fox, Tawny Owl and the others are near starvation, and resort to leaving the park and stealing food from farms and rubbish bins. They have to band together and use their cunning to survive. This was a sweet book that reminded me of my childhood love of anthropomorphized animal stories (like Watership Down and the Redwall series). I doubt I’ll read another from the series, but this was a quaint read for the season.

Once a year or so I encounter a book that’s so flawlessly written you could pick out just about any sentence and marvel at its construction. That’s certainly the case here. I never want to go to Greenland; English winters are quite dark and cold enough for me, and I don’t know if I could stomach seal meat at all, let alone for most meals and often raw. But that’s okay: I don’t need to book a flight to Qaanaaq, because through reading this I’ve already been in Greenland in every season, and I thoroughly enjoyed my armchair trek. Impressively, Ehrlich is always describing the same sorts of scenery, and yet every time finds a fresh way to write about ice and sun glare and frigid temperatures. I’ll be looking into her other books for sure.

Once a year or so I encounter a book that’s so flawlessly written you could pick out just about any sentence and marvel at its construction. That’s certainly the case here. I never want to go to Greenland; English winters are quite dark and cold enough for me, and I don’t know if I could stomach seal meat at all, let alone for most meals and often raw. But that’s okay: I don’t need to book a flight to Qaanaaq, because through reading this I’ve already been in Greenland in every season, and I thoroughly enjoyed my armchair trek. Impressively, Ehrlich is always describing the same sorts of scenery, and yet every time finds a fresh way to write about ice and sun glare and frigid temperatures. I’ll be looking into her other books for sure. This short novel from 2005 deserves to be better known. It reminded me of

This short novel from 2005 deserves to be better known. It reminded me of  This is my favorite of the three Knausgaard books I’ve read so far, and miles better than his Autumn. These short essays successfully evoke the sensations of winter and the conflicting emotions elicited by family life and childhood memories. The series is, loosely speaking, a set of instruction manuals for his unborn daughter, who is born a month premature in the course of this volume. So in the first book he starts with the basics of bodily existence – orifices, bodily fluids and clothing – and now he’s moving on to slightly more advanced but still everyday things she’ll encounter, like coins, stuffed animals, a messy house, toothbrushes, and the moon. I’ll see out this series, and see afterwards if I have the nerve to return to My Struggle.

This is my favorite of the three Knausgaard books I’ve read so far, and miles better than his Autumn. These short essays successfully evoke the sensations of winter and the conflicting emotions elicited by family life and childhood memories. The series is, loosely speaking, a set of instruction manuals for his unborn daughter, who is born a month premature in the course of this volume. So in the first book he starts with the basics of bodily existence – orifices, bodily fluids and clothing – and now he’s moving on to slightly more advanced but still everyday things she’ll encounter, like coins, stuffed animals, a messy house, toothbrushes, and the moon. I’ll see out this series, and see afterwards if I have the nerve to return to My Struggle. Many poetry volumes get a middling rating from me because some of the poems are memorable but others do nothing for me. This is on the longer side for a collection at 120+ pages, but only a handful of its poems fell flat. The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe (my cover depicts the Avebury stone circle in the gloom), menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. The title poem, which appears first, has a slightly melancholy tone with its focus on the short days of winter, but the poet defiantly asserts meaning despite the mood: “Even the dead of winter: it seethes with more / than I can ever live to name and speak.” Piercy was a great discovery, and I’ll be trying lots more of her books from various genres.

Many poetry volumes get a middling rating from me because some of the poems are memorable but others do nothing for me. This is on the longer side for a collection at 120+ pages, but only a handful of its poems fell flat. The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe (my cover depicts the Avebury stone circle in the gloom), menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. The title poem, which appears first, has a slightly melancholy tone with its focus on the short days of winter, but the poet defiantly asserts meaning despite the mood: “Even the dead of winter: it seethes with more / than I can ever live to name and speak.” Piercy was a great discovery, and I’ll be trying lots more of her books from various genres. The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden: Some striking turns of phrase, an enchanting wintry atmosphere … but a little Disney-fied for me. I got this free for Kindle so may come back to it at some point.

The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden: Some striking turns of phrase, an enchanting wintry atmosphere … but a little Disney-fied for me. I got this free for Kindle so may come back to it at some point. Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!).

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!). Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room. Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This isn’t a happy family story. It’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate. Yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right, and it’s pulsing with emotion. One theme is how there can be different interpretations of the same events even within a small family. The novel is particularly strong on atmosphere, reminding me of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea and Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. Fuller also manages her complex structure very well.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This isn’t a happy family story. It’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate. Yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right, and it’s pulsing with emotion. One theme is how there can be different interpretations of the same events even within a small family. The novel is particularly strong on atmosphere, reminding me of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea and Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. Fuller also manages her complex structure very well.