Tag Archives: Marxism

May Graphic Novels by Alison Bechdel, Peter Kuper & Craig Thompson

May has been chock-full of new releases for me! For this first batch of reviews, I’m featuring three fantastic graphic novels that have made it onto my Best of 2025 (so far) list. I don’t read graphic books as often as I’d like to – my library tends to major on superhero comics and manga, which aren’t my cup of tea – but I sometimes get a chance to access them for paid review purposes. (The first two below are ones I was sent for potential Shelf Awareness reviews, but I missed the deadlines.) Reading these took me back to the early 2010s when I worked for a university library in South London and would walk to Lambeth Library on my lunch breaks to borrow huge piles of books, mostly taking advantage of their excellent graphic novel selection. That was where my education and fascination began.

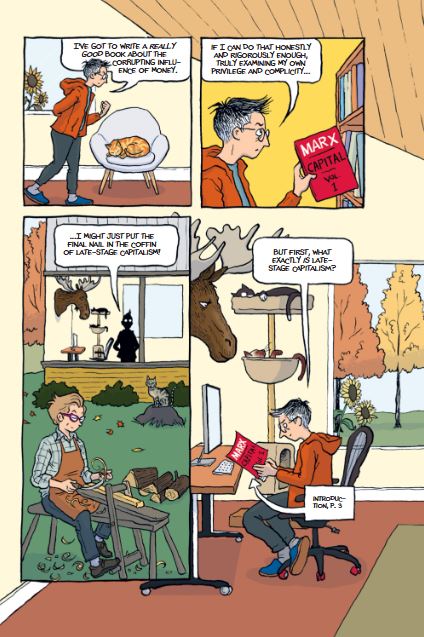

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now. Fun Home was among the first graphic books I read and is a great choice if you’re new to this form of storytelling. It’s a family memoir about her father’s funeral home business and closeted lifestyle, which emerged shortly after her own coming-out – and shortly before his accidental death. In Spent, Alison and her handy wife Holly live on a Vermont pygmy goat farm. Alison has writer’s block and is struggling financially despite her famous memoir about her taxidermist father having been made into a successful TV series, Death & Taxidermy. Mostly, she’s consumed with anxiety about the state of the world, what with the ongoing pandemic, her sister’s right-wing opinions, and the litany of awful headlines. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” she exclaims.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now. Fun Home was among the first graphic books I read and is a great choice if you’re new to this form of storytelling. It’s a family memoir about her father’s funeral home business and closeted lifestyle, which emerged shortly after her own coming-out – and shortly before his accidental death. In Spent, Alison and her handy wife Holly live on a Vermont pygmy goat farm. Alison has writer’s block and is struggling financially despite her famous memoir about her taxidermist father having been made into a successful TV series, Death & Taxidermy. Mostly, she’s consumed with anxiety about the state of the world, what with the ongoing pandemic, her sister’s right-wing opinions, and the litany of awful headlines. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” she exclaims.

Then Alison has an idea for a book – or maybe a reality TV series – called $UM that will wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored in Spent, which is composed of 12 “episodes” titled after Marxist terminology. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living: a commune, a throuple, nonbinary identity, unpaid internships, Just Stop Oil demos, and the influencer lifestyle versus rejection of technology. It’s (auto)fiction exaggerated to the brink of absurdity, with details changed enough to mock but not enough to hide (e.g., she’s published by “Megalopub,” the hardware store is “Home Despot,” her show airs on “Schmamazon”).

Tiny details in the drawings reward close attention, such as Alison and Holly’s five cats’ antics during their morning routine, and a stuffed moose head rolling its eyes. It’s the funniest I can remember Bechdel being, with much broad humour derived from the outrageous screen mangling of her book – cannibalism, volcanoes and dragons come out of nowhere – and her middle-class friends’ hand-wringing over their liberal credentials. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close as Alison has the epiphany that she can’t fix everything herself so must simply do what she can, “with a little help from her annoying, tender-hearted, and utterly luminous friends.”

Accessed as an e-book from Mariner Books. Published in the UK by Jonathan Cape (Penguin).

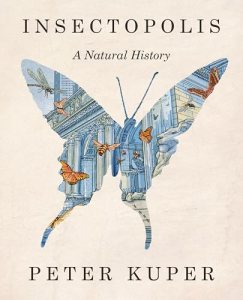

Insectopolis: A Natural History by Peter Kuper

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s Ruins, which features monarch migration and has as protagonist a laid-off Natural History Museum entomologist. Here insects have even more of a starring role. The E. O. Wilson epigraph sets the stage: “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” We follow an African American brother-and-sister pair, the one dubious and the other eager, as they walk downtown to the New York Public Library. The sister, who holds a PhD in entomology, promises that its exhibition on insects is going to be amazing. But just before they reach the building, a red alert flashes up on every smartphone and sirens start blaring. A week later, the city is a ruin of overturned cabs and debris. Only insects remain and, group by group, they guide readers through the empty exhibit, interacting within and across species.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s Ruins, which features monarch migration and has as protagonist a laid-off Natural History Museum entomologist. Here insects have even more of a starring role. The E. O. Wilson epigraph sets the stage: “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” We follow an African American brother-and-sister pair, the one dubious and the other eager, as they walk downtown to the New York Public Library. The sister, who holds a PhD in entomology, promises that its exhibition on insects is going to be amazing. But just before they reach the building, a red alert flashes up on every smartphone and sirens start blaring. A week later, the city is a ruin of overturned cabs and debris. Only insects remain and, group by group, they guide readers through the empty exhibit, interacting within and across species.

It’s a sly blend of science, history, stories and silliness. I loved the scenes of mosquitoes and ants railing against how they’ve been depicted as villainous, and dignified dung beetles resisting scatological jokes and standing up for their importance in ecosystems. There are interesting interludes about insects in literature (not just Kafka and Nabokov, but the Japanese graphic novel The Book of Human Insects by Osamu Tezuka), and unsung heroines of entomology get their moment in the sun. The pages in which Margaret Collins, an African American termite researcher in the 1950s, and Rachel Carson appear to a dragonfly as ghosts and tell their stories of being dismissed by male researchers were among my favourites. Informative and entertaining at once; what could be better? Welcome our insect overlords!

Accessed as an e-book from W. W. Norton & Company.

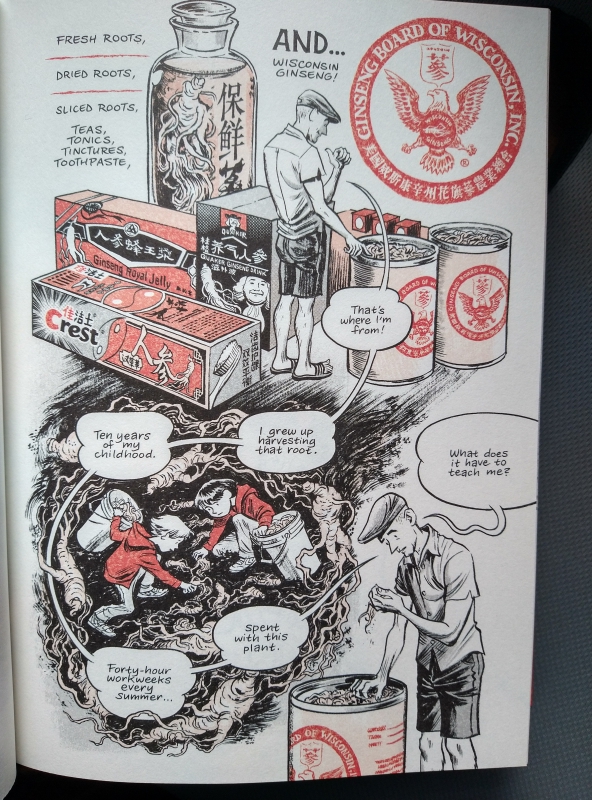

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir, Blankets, about his first love and loss of faith. When I read this blurb, I worried the niche subject couldn’t possibly sustain my attention for nearly 450 pages. But I was wrong; this is a vital book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. Theirs was a blue collar and highly religious family, but Thompson and his little brother Phil were allowed to spend their earnings from the back-breaking labour of weeding and picking rocks as they pleased. Each hour, each dollar, meant a new comic from the pharmacy. “Comics helped me survive my childhood. But what will help me survive my adulthood?” Thompson asks.

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir, Blankets, about his first love and loss of faith. When I read this blurb, I worried the niche subject couldn’t possibly sustain my attention for nearly 450 pages. But I was wrong; this is a vital book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. Theirs was a blue collar and highly religious family, but Thompson and his little brother Phil were allowed to spend their earnings from the back-breaking labour of weeding and picking rocks as they pleased. Each hour, each dollar, meant a new comic from the pharmacy. “Comics helped me survive my childhood. But what will help me survive my adulthood?” Thompson asks.

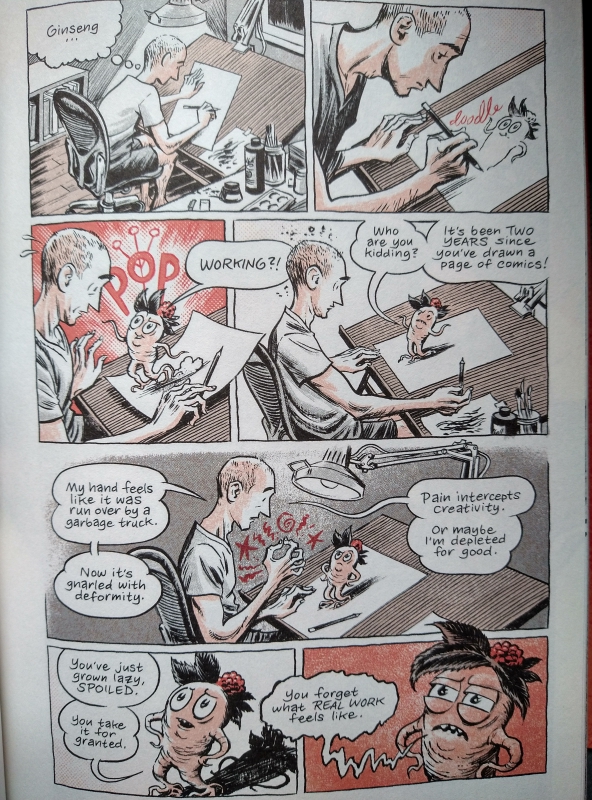

Together with Phil, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation practices, lore, and medicinal uses. As he meets producers – including a Hmong man whose early life mirrors his own – he feels sheepish about how he makes a living: “I carry this working-class guilt – what I do isn’t real work.” When his livelihood is threatened by worsening autoimmune conditions, he tries everything from acupuncture to psychotherapy to save his hands and his creativity.

This chunky book has an appealing earth-tones palette and shifts smoothly between locations and styles, memories and research. When interviewing growers and Chinese medicine practitioners, the depictions are almost photorealistic, but there are also superhero pastiche panels and a cute ginseng mascot who pops up throughout the book. Like Spent, this pulls in class and economic issues in a lighthearted way and also explores its own composition process.

The story of ginseng is often sobering, involving the exploitation of immigrants (in the Notes, Thompson regrets that he was unable to speak with any of the Mexican migrant workers on whom the American ginseng harvest now depends), soil degradation, and pesticide pollution. The roots of the title are both literal and symbolic of the family story that unfolds in parallel. Both strands are captivating, but especially the autobiographical material: Thompson’s relationship with Phil, his new understanding but ongoing frustration with his parents, and the way all three siblings exhibit the damage of their upbringing – Phil’s marriage is crumbling; their sister Sarah, who has moved 26 times as an adult, wonders what she’s running from. A conversation with a Chinese herbal pharmacist gets to the heart of the matter: “I learned home is not WHERE I am. Home is HOW I am.”

Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers out there.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. Published in the USA by Pantheon (Penguin).

Three on a Theme: “Heart”

From a vibrant novel about trauma and second chances to a cultural history of our knowledge of the organ and its symbols, via a true story of the effects of being struck by lightning, what might these three disparate books have to tell us about the human heart on Valentine’s Day?

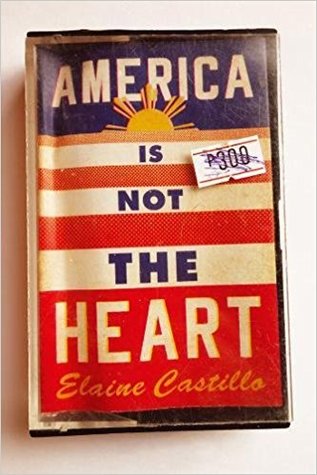

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo (2018)

This was criminally overlooked a few years ago, though I do remember Naomi F. featuring it on The Writes of Womxn. Set in the early 1990s in the Filipino immigrant neighborhoods of the Bay Area in California, it throws you into an unfamiliar culture at the deep end. There are lots of different ethnicities mentioned, and snippets of various languages (not just Tagalog, the one I knew of previously) run through the text, sometimes translated but often not. It’s a complex, confident debut novel that references episodes from the history of the Philippines of which I was mostly ignorant – genocide and reforms, dictatorship and a Marxist resistance.

Geronima is a family name for the De Veras; not many realize that Hero, in her mid-thirties and newly arrived in the USA as an undocumented immigrant, and her cousin Roni, her uncle Pol’s seven-year-old daughter, share the same first name. Hero is estranged from her wealthy parents: they were friendly with the Marcos clan, while she ran away to serve as a doctor in the New People’s Army for 10 years. We gradually learn that she was held in a prison camp for two years and subjected to painful interrogations. Still psychologically as well as physically marked by the torture, she is reluctant to trust anyone. She stays under the radar, just taking Roni to and from school and looking after her while her parents are at work.

Geronima is a family name for the De Veras; not many realize that Hero, in her mid-thirties and newly arrived in the USA as an undocumented immigrant, and her cousin Roni, her uncle Pol’s seven-year-old daughter, share the same first name. Hero is estranged from her wealthy parents: they were friendly with the Marcos clan, while she ran away to serve as a doctor in the New People’s Army for 10 years. We gradually learn that she was held in a prison camp for two years and subjected to painful interrogations. Still psychologically as well as physically marked by the torture, she is reluctant to trust anyone. She stays under the radar, just taking Roni to and from school and looking after her while her parents are at work.

When Roni’s mother Paz, a medical professional, turns to traditional practices for help with Roni’s extreme eczema, Hero takes Roni to the Boy’s BBQ & Grill / Mai’s Hair and Beauty complex to see Adela Cabugao, a Filipina faith healer. The restaurant becomes a refuge for Hero and Roni – a place where they hang out with Adela’s granddaughter, Rosalyn, and her friends in the long hours Paz is away at her hospital jobs, eating and watching videos or reading Asian comics. Over the next few years Rosalyn introduces Hero to American holidays and customs. Castillo is matter-of-fact about Hero’s hook-ups with guys and girls but never strident about a bisexuality label. Hero pursues sex but remains wary of romance.

The everydayness of life here – car rides, cassette tapes, job applications, foil trays of food – contrasts with too-climactic memories. Though the plot can meander, there’s forward motion in that Hero shifts from a survival mindset into an assurance of safety that allows her to start rebuilding her life. I loved the 1990s as a setting. The characters shine and the dialogue (not in speech marks) feels utterly authentic in this fresh immigration story. My only minor disappointment was that second-person narration does not recur beyond a chapter about Paz and one about Rosalyn. The title riffs on a classic of Filipino American literature, America Is in the Heart (1946) by Carlos Bulosan, though I didn’t explore that comparison; it’s a novel that opens up real Google wormholes, should you take up the challenge. Castillo’s vibrant, distinctive voice reminded me of authors from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Viet Thanh Nguyen. Please tell me she has another book in the works.

Favorite line: “Baggage means no matter how far you go, no matter how many times you immigrate, there are countries in you you’ll never leave.”

Words about the heart:

“Hero had no truck with people for whom the heart was a dreamt-up thing, held together by divine saliva, a place where gods of love still made their beds. A heart was something you could buy on the street, six to a skewer … served with garlicky rice and atsuete oil.”

“Hero had never even felt ambivalence toward Pol … She’d only ever known what it felt like to love him, to keep the minor altar of admiration for him in her heart well cleaned, its flowers rotless and blooming. What she hadn’t known was that her love was a room, cavernous, and hate could enter there, too; curl up in the same bed, blanketed and sleep-warm.”

“May tinik sa puso. You know what that means? Like she has a fishbone in the heart. She’s angry about something.”

Source: Free from a neighbor

My rating:

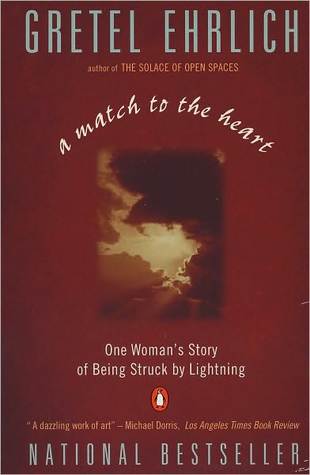

A Match to the Heart by Gretel Ehrlich (1994)

In August 1991, as a summer thunderstorm approached her Wyoming ranch, Ehrlich was struck by lightning. Although she woke up in a pool of blood, her dogs stayed by her side and she was able to haul herself the quarter-mile home and call 911 before she collapsed completely. Being hit by so much electricity (10–30 million volts) had lasting effects on her health. Her heart rhythms were off and she struggled with fatigue for years to come. In a sense, she had died and come back to a subtly different life.

In August 1991, as a summer thunderstorm approached her Wyoming ranch, Ehrlich was struck by lightning. Although she woke up in a pool of blood, her dogs stayed by her side and she was able to haul herself the quarter-mile home and call 911 before she collapsed completely. Being hit by so much electricity (10–30 million volts) had lasting effects on her health. Her heart rhythms were off and she struggled with fatigue for years to come. In a sense, she had died and come back to a subtly different life.

After relocating to the California coast, she shadows her cardiologist and observes open-heart surgery, attends the annual Lightning Strike and Electric Shock Conference, and explores a new liminal land of beaches and islands. Again and again, she uses metaphors of the bardo and the phoenix to make sense of the in-between state she perhaps still inhabits. Full-on medical but also intriguingly mystical, this is another solid memoir from a phenomenal author. I know of her more as a nature/travel writer (This Cold Heaven is fantastic) and have another of her books on the shelf, The Solace of Open Spaces.

Words about the heart:

“Above and beyond the drama of cardiac arrest, or the threat of it, is the metaphorical territory of the heart: if love desists, if passion arrests, if compassion stops circulating through the arteries of society, then civilization, such as it is, will stop.”

“The thoracic cavity must have been the place where human music began, the first rhythm was the beat of the heart, and after that initial thump, waltzes and nocturnes, preludes and tangos rang out, straight up through flesh and capillary, nerve ganglion and epidermal layer, resonating in sternum bone: it wasn’t light that created the world but sound.”

Source: Birthday gift (secondhand) a couple years ago

My rating:

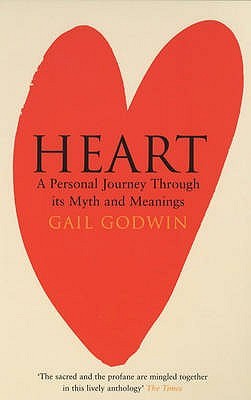

Heart: The Story of Its Myths and Meanings by Gail Godwin (2001)

I’d read one novel and one memoir by Godwin and was excited to learn that she had once written a wide-ranging study of the religious and literary meanings overlaid on the heart. While there are some interesting pinpricks here, the delivery is shaky: she starts off with a dull, quotation-stuffed, chronological timeline, all too thorough in its plod from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Industrial Revolution. I quickly resorted to skimming and my eye alighted on Chinese philosophy (“True knowledge, Confucius taught, lies in the heart. He created and taught an ethical system that emphasized ‘human-heartedness,’ stressing balance in the heart”) and Dickens’s juxtaposition of facts and emotion in Hard Times.

I’d read one novel and one memoir by Godwin and was excited to learn that she had once written a wide-ranging study of the religious and literary meanings overlaid on the heart. While there are some interesting pinpricks here, the delivery is shaky: she starts off with a dull, quotation-stuffed, chronological timeline, all too thorough in its plod from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Industrial Revolution. I quickly resorted to skimming and my eye alighted on Chinese philosophy (“True knowledge, Confucius taught, lies in the heart. He created and taught an ethical system that emphasized ‘human-heartedness,’ stressing balance in the heart”) and Dickens’s juxtaposition of facts and emotion in Hard Times.

Part Two, “Heart Themes in Life and Art,” initially seemed more promising in that it opens with the personal stories of her half-brother’s death in a murder–suicide and her mother’s fatal heart attack while driving a car, but I didn’t glean much from her close readings of, e.g. Joseph Conrad and Elizabeth Bowen. Still, I’ll keep this on the shelf as a reference book for any specific research I might do in the future.

Source: Bookbarn International on February 2020 visit (my last time there)

My rating:

If you read just one … It’s got to be America Is Not the Heart. (Though, if you’re also interested in first-person medical accounts, add on A Match to the Heart.)