Tag Archives: memoir in essays

The Best Books from the First Half of 2025

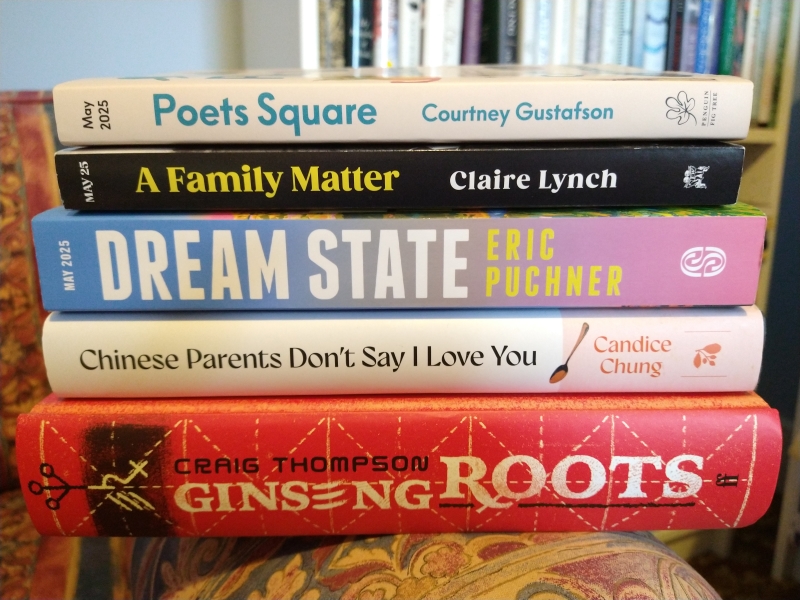

Hard to believe it, but it’s that time of year already. It’s the ninth year in a row that I’ve been making a first-half superlatives list. It remains to be seen how many of these will make it onto my overall best-of year rundown, but for now, these are my 16 favourite 2025 releases that I’ve read so far (representing the top ~21% of my current-year reading). Pictured below are the ones I read in print; all the others were e-copies. Links are to my full reviews.

Fiction

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or maybe a reality TV series – called $UM that will wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or maybe a reality TV series – called $UM that will wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse: Twelve first-person narratives voiced by people in crisis, for whom encounters with strangers tender the possibility of transformation. In the title story, the narrator is taken hostage in a convenience store hold-up. Others are set in Thailand and Japan as well as various U.S. states. Krouse focuses on young women presented with dilemmas and often eschews tidy endings, leaving characters on the brink and allowing readers to draw inferences. Fans of Danielle Evans and Lauren Groff have a treat in store.

Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse: Twelve first-person narratives voiced by people in crisis, for whom encounters with strangers tender the possibility of transformation. In the title story, the narrator is taken hostage in a convenience store hold-up. Others are set in Thailand and Japan as well as various U.S. states. Krouse focuses on young women presented with dilemmas and often eschews tidy endings, leaving characters on the brink and allowing readers to draw inferences. Fans of Danielle Evans and Lauren Groff have a treat in store.

Insectopolis: A Natural History by Peter Kuper: “If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” (E. O. Wilson) After an unspecified apocalypse, only insects remain. Group by group, they guide readers through an empty New York Public Library exhibit, interacting within and across species. It’s a sly blend of science, history, stories and silliness. There are interludes about insects in literature and unsung heroines of entomology. Informative and entertaining at once; what could be better? Welcome our insect overlords!

Insectopolis: A Natural History by Peter Kuper: “If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” (E. O. Wilson) After an unspecified apocalypse, only insects remain. Group by group, they guide readers through an empty New York Public Library exhibit, interacting within and across species. It’s a sly blend of science, history, stories and silliness. There are interludes about insects in literature and unsung heroines of entomology. Informative and entertaining at once; what could be better? Welcome our insect overlords!

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Cross Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Cross Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Nonfiction

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung: A vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. Chung reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” The essays range in time and style, delicately contrasting past and present, singleness and being partneredr.

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung: A vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. Chung reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” The essays range in time and style, delicately contrasting past and present, singleness and being partneredr.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Edge of the World: An Anthology of Queer Travel Writing, ed. Alden Jones: Sixteen authors of diverse sexual orientations and genders contrast here and there and then and now as they narrate sensory memories and personal epiphanies. In these pieces, time abroad sparks clarity. There’s power in queer solidarity, whether one is in Berlin or Key West. Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s piece is the highlight. A stellar anthology of miniature travelogues that are as illuminating about identity as they are about the places they feature.

Edge of the World: An Anthology of Queer Travel Writing, ed. Alden Jones: Sixteen authors of diverse sexual orientations and genders contrast here and there and then and now as they narrate sensory memories and personal epiphanies. In these pieces, time abroad sparks clarity. There’s power in queer solidarity, whether one is in Berlin or Key West. Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s piece is the highlight. A stellar anthology of miniature travelogues that are as illuminating about identity as they are about the places they feature.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Essays on the Future that Never Was) by Colette Shade: Shade’s debut collection contains 10 perceptive essays that contrast the promise and political pitfalls of “the Y2K Era” (1997–2008). The author recalls the thrill of early Internet use and celebrity culture. Consumerism was a fundamental doctrine but the financial crash prompted a loss of faith in progress. Outer space motifs, reality television, Smashmouth lyrics: it’s a feast of millennial nostalgia. Yet this hard-hitting work of cultural criticism, recommended to Jia Tolentino fans, reminisces only to burst bubbles.

Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Essays on the Future that Never Was) by Colette Shade: Shade’s debut collection contains 10 perceptive essays that contrast the promise and political pitfalls of “the Y2K Era” (1997–2008). The author recalls the thrill of early Internet use and celebrity culture. Consumerism was a fundamental doctrine but the financial crash prompted a loss of faith in progress. Outer space motifs, reality television, Smashmouth lyrics: it’s a feast of millennial nostalgia. Yet this hard-hitting work of cultural criticism, recommended to Jia Tolentino fans, reminisces only to burst bubbles.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Poetry

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine: McAlpine’s second collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes. She expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets; mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Just my sort of poetry: sweet on the ear, rooted in nature and the everyday.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine: McAlpine’s second collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes. She expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets; mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Just my sort of poetry: sweet on the ear, rooted in nature and the everyday.

Which of these grab your attention? What other 2025 releases should I catch up on?

Reading Ireland Month, Part II: Barrett, More Donoghue, O’Farrell x 2

My second set of contributions to Cathy’s Reading Ireland Month. Emma Donoghue also appeared in my first instalment of reviews. Today I’m featuring her latest novel, published just a couple of weeks ago, and taking a quick look at a few other Irish books I’ve read recently: a light-hearted debut featuring small-town criminals, and two by Maggie O’Farrell: a reread of her only nonfiction work to date (for book club), and her newest children’s book.

Wild Houses by Colin Barrett (2024)

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in Trespasses. Overall, I felt that this was nicely written but that Barrett’s talent was somewhat wasted on a thin story. I’ve encountered similar plots in better books by Paul Murray and Donal Ryan. (Free from the publisher)

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in Trespasses. Overall, I felt that this was nicely written but that Barrett’s talent was somewhat wasted on a thin story. I’ve encountered similar plots in better books by Paul Murray and Donal Ryan. (Free from the publisher) ![]()

The Paris Express by Emma Donoghue

Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters.

Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters.

The premise is appealing: a train hurtling toward catastrophe is in a sense a locked room, seeding much drama and intrigue. A young female radical is on board with a bomb, so all along you speculate about whether she’ll set it off and when. While I found the general thrust engaging, it was harder to develop interest in the large cast of characters. I also found the passages personifying the train (she “carries death in her belly”) hokey and thought that, as has sometimes been the case with Donoghue’s historical work, there’s too much research that’s there just for the sake of it, because she came across a fact she found fascinating and couldn’t bear to leave out (“These days every public building has three rubbish bins—one for the reclaiming of paper and cloth, the next for glass, ceramics, and oyster shells, and the last for perishables, which is where she drops the handkerchief.”). So this was enjoyable enough but not among her best. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell (2017)

This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle.

This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle.

My original review from 2018:

We are, all of us, wandering about in a state of oblivion, borrowing our time, seizing our days, escaping our fates, slipping through loopholes, unaware of when the axe may fall.

O’Farrell captures fragments of her life through 17 essays on life-threatening illnesses and other narrow escapes she’s experienced. The pieces aren’t in chronological order and aren’t intended to be comprehensive. Instead, they crystallize the fear and pain of particular moments in time, and are rendered with the detail you’d expect from a scene in one of her novels. (Indeed, you can spot a lot of the real-life influences on her fiction, particularly This Must Be the Place – travels in China and Chile; eczema and stammering.)

She’s been mugged at machete point, has nearly drowned several times, had a risky first labour, and was almost the victim of a serial killer. (My life feels awfully uneventful by comparison!) But the best section of the book is its final quarter: an essay about her childhood encephalitis and its lasting effects, followed by another about her daughter’s extreme allergies. Only now, as a mother, can she understand how terrifying it must have been for her parents to wait at her side during days when she might not have survived. O’Farrell depicts parenthood better than any other author I can think of – letting those of us who haven’t experienced it do so vicariously. (Gift from my wish list)

My original rating (2018): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

When the Stammer Came to Stay by Maggie O’Farrell (2024)

This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

When the Stammer Came to Stay is a perfect follow-on to I Am, I Am, I Am because it, too, draws on O’Farrell’s personal struggles. It’s the fable-like story of two sisters, Bea and Min, who share an attic room. The one is perfectly tidy; the other is a messy tomboy. When the stammer, pictured as a blob of silver ectoplasm above the shoulder, starts stealing Min’s words, they gather advice from their parents and the lodgers about how she can accept her new reality instead of fighting it or closing herself off by not speaking at all. The mycologist’s symbiosis metaphor is perhaps a bit too neat, but it contrasts with the impish connotations of the dibbuk, another useful parallel the girls discover. With this I’ve now read O’Farrell’s complete published works! ![]()