Adventures in Rereading: The History of Love by Nicole Krauss for Valentine’s Day

Special Valentine’s edition. Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet manage a themed post featuring one or more books with “Love” or “Heart” in the title. This is the ninth year in a row, in fact – after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024!

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library)

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Finishing my reread during a coffee date in Hungerford this morning.

My original rating (2011): ![]()

When I first read this, I mostly considered it in comparison to Krauss’s former husband Jonathan Safran Foer’s work. (I’ve long since read everything by both of them.) I noted then that it

has a lot of elements in common with Everything is Illuminated, such as a preoccupation with Eastern European and Jewish ancestry, quirky methods of narration including multiple voices, and a sweet humour that lies alongside such heart-rending stories of family and loss that tears are never far from your eyes. Leo Gursky and Alma Singer are delightful and distinct characters. I wasn’t sure about the missing/plagiarized/mistaken The History of Love itself; the ruined copies, the different translations, the way the manuscript was constantly changing hands – all this was intriguing, but the book itself was a postmodern jumble of magic realism and pointless meanderings of thought.

Dang, I was harsh! But admirably pithy about the plot. It’s intriguing that I’ve successfully reread Krauss but failed with Foer when I attempted Everything is Illuminated again in 2020. Reading the first, 9/11-set section of Confessions by Catherine Airey, I’ve also been recalling his Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and thinking it probably wouldn’t stand up to a reread either. I suspect I’d find it mawkish, especially with its child narrator. Alma evades that trap, perhaps by being that little bit older, though she sounds young because of how geeky and sheltered she is.

Book Serendipity, Late 2020 into 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list some of my occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. The following are in chronological order.

- The Orkney Islands were the setting for Close to Where the Heart Gives Out by Malcolm Alexander, which I read last year. They showed up, in one chapter or occasional mentions, in The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange and The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields, plus I read a book of Christmas-themed short stories (some set on Orkney) by George Mackay Brown, the best-known Orkney author. Gavin Francis (author of Intensive Care) also does occasional work as a GP on Orkney.

- The movie Jaws is mentioned in Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe and Landfill by Tim Dee.

- The Sámi people of the far north of Norway feature in Fifty Words for Snow by Nancy Campbell and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave.

- Twins appear in Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe and Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey. In Vesper Flights Helen Macdonald mentions that she had a twin who died at birth, as does a character in Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce. A character in The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard is delivered of twins, but one is stillborn. From Wrestling the Angel by Michael King I learned that Janet Frame also had a twin who died in utero.

- Fennel seeds are baked into bread in The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave and The Strays of Paris by Jane Smiley. Later, “fennel rolls” (but I don’t know if that’s the seed or the vegetable) are served in Monogamy by Sue Miller.

- A mistress can’t attend her lover’s funeral in Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan and Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey.

- A sudden storm drowns fishermen in a tale from Christmas Stories by George Mackay Brown and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave.

Silver Spring, Maryland (where I lived until age 9) is mentioned in one story from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss and is also where Peggy Seeger grew up, as recounted in her memoir First Time Ever. Then it got briefly mentioned, as the site of the Institute of Behavioral Research, in Livewired by David Eagleman.

Silver Spring, Maryland (where I lived until age 9) is mentioned in one story from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss and is also where Peggy Seeger grew up, as recounted in her memoir First Time Ever. Then it got briefly mentioned, as the site of the Institute of Behavioral Research, in Livewired by David Eagleman.

- Lamb is served with beans at a dinner party in Monogamy by Sue Miller and Larry’s Party by Carol Shields.

- Trips to Madagascar in Landfill by Tim Dee and Lightning Flowers by Katherine E. Standefer.

Hospital volunteering in My Year with Eleanor by Noelle Hancock and Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession.

Hospital volunteering in My Year with Eleanor by Noelle Hancock and Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession.

- A Ronan is the subject of Emily Rapp’s memoir The Still Point of the Turning World and the author of Leonard and Hungry Paul (Hession).

- The Magic Mountain (by Thomas Mann) is discussed in Scattered Limbs by Iain Bamforth, The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, and Snow by Marcus Sedgwick.

- Frankenstein is mentioned in The Biographer’s Tale by A.S. Byatt, The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, and Snow by Marcus Sedgwick.

- Rheumatic fever and missing school to avoid heart strain in Foreign Correspondence by Geraldine Brooks and Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller. Janet Frame also had rheumatic fever as a child, as I discovered in her biography.

- Reading two novels whose titles come from The Tempest quotes at the same time: Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame and This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson.

- A character in Embers by Sándor Márai is nicknamed Nini, which was also Janet Frame’s nickname in childhood (per Wrestling the Angel by Michael King).

- A character loses their teeth and has them replaced by dentures in America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo and The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Also, the latest cover trend I’ve noticed: layers of monochrome upturned faces. Several examples from this year and last. Abstract faces in general seem to be a thing.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Thinking Realistically about Reading Plans for the Rest of the Year

The other year I did something dangerous: I started an exclusive Goodreads shelf (i.e., an option besides the standard “Read,” “Currently Reading” and “Want to Read”) called “Set Aside Temporarily,” where I stick a book I have to put on hiatus for whatever reason, whether I’d read 20 pages or 200+. This enabled me to continue in my bad habit of leaving part-read books lying around. I know I’m unusual for taking multi-reading to an extreme with 20‒30 books on the go at a time. For the most part, this works for me, but it does mean that less compelling books or ones that don’t have a review deadline attached tend to get ignored.

I swore I’d do away with the Set Aside shelf in 2020, but it hasn’t happened. In fact, I made another cheaty shelf, “Occasional Reading,” for bedside books and volumes I read a few pages in once a week or so (e.g. devotional works on lockdown Sundays), but I don’t perceive this one to be a problem; no matter if what’s on it carries over into 2021.

Looking at the five weeks left in the year and adapting the End of the Year Book Tag Laura did recently, I’ve been thinking about what I can realistically read in 2020.

Is there a book that you started that you still need to finish by the end of the year?

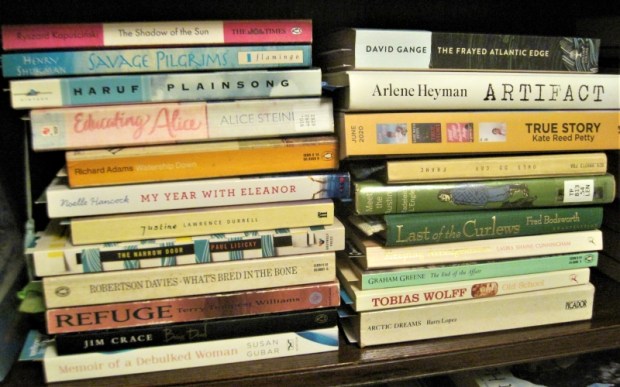

So many! I hope to finish most, if not all, of the books I’m currently reading, plus I’d like to clear these set aside stacks as much as possible. If nothing else, I have to finish the two review books (Gange and Heyman, on the top of the right-hand stack).

Name some books you want to read by the end of the year.

I still have these four print books to review on the blog. The Shields, a reissue, is for a December blog tour; I might save the snowy one for later in the winter.

I will also be reading an e-copy of Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce for a BookBrowse review.

The 2020 releases I’d placed holds on are still arriving to the library for me. Of them, I’d most like to get to:

The 2020 releases I’d placed holds on are still arriving to the library for me. Of them, I’d most like to get to:

- Mr Wilder & Me by Jonathan Coe

- Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways by Derek Gow

- To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss

My Kindle is littered with 2020 releases I purchased or downloaded from NetGalley and intended to get to this year, including buzzy books like My Dark Vanessa. I don’t read so much on my e-readers anymore, but I’ll see if I can squeeze in one or two of these:

Fat by Hanne Blank

Fat by Hanne Blank- Marram by Leonie Charlton

- D by Michel Faber

- Alone Together: Love, Grief, and Comfort in the Time of COVID-19, edited by Jennifer Haupt

- Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann

- Avoid the Day by Jay Kirk*

- World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil*

*These were on my Most Anticipated list for the second half of 2020.

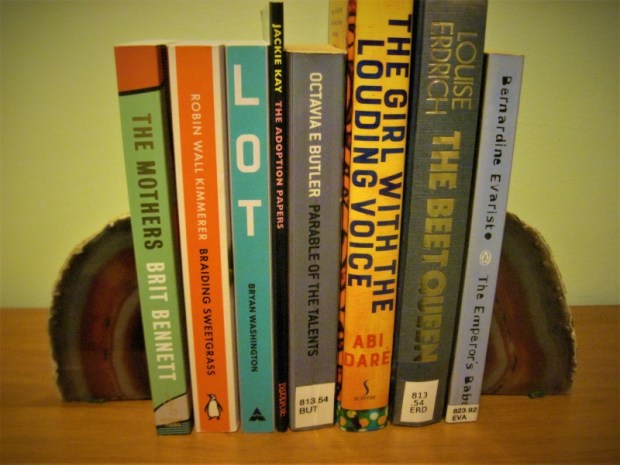

The Nezhukumatathil would also count towards the #DiverseDecember challenge Naomi F. is hosting. I assembled this set of potentials: four books that I own and am eager to read on the left, and four books from libraries on the right.

Is there a book that could still shock you and become your favorite of the year?

Two books I didn’t finish until earlier this month, The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel and Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald, leapt into contention for first place for the year in fiction and nonfiction, respectively, and it’s entirely possible that something I’ve got out from the library or on my Kindle (as listed above) could be just as successful. That’s why I wait until the last week of the year to finalize Best Of lists.

Do you have any books that are partly read and languishing? How do you decide on year-end reading priorities?

Paul Auster Reading Week: Oracle Night and Report from the Interior

Paul Auster Reading Week continues! Be sure to check out Annabel’s excellent post on why you should try Auster. On Monday I reviewed Winter Journal and the New York Trilogy. Adding in last year’s review of Timbuktu, I’ve now read six of Auster’s books and skimmed another one (the sequel to Winter Journal). It’s been great to have this project as an excuse to get more familiar with his work and start to recognize some of the recurring tropes.

Oracle Night (2003)

This reminded me most of The Locked Room, the final volume of the New York Trilogy. There’s even a literal locked room in a book within the book by the narrator, a writer named Sidney Orr. It’s 1982 and Orr is convalescing from a sudden, life-threatening illness. At a stationer’s shop, he buys a fine blue notebook from Portugal, hoping its beauty will inspire him to resume his long-neglected work. When he and his wife Grace go to visit John Trause, Grace’s lifelong family friend and a fellow novelist, Orr learns that Trause uses the same notebooks. Only the blue ones, mind you. No other color fosters the same almost magical creativity.

For long stretches of the novel, Orr is lost in his notebook (“I was there, fully engaged in what was happening, and at the same time I wasn’t there—for the there wasn’t an authentic there anymore”), writing in short, obsessive bursts. In one project, a mystery inspired by an incident from The Maltese Falcon, Nick Bowen, a New York City editor, has a manuscript called Oracle Night land on his desk. Spooked by a near-death experience, he flees to Kansas City, where he gets a job working on a cabdriver’s phone book archive, “The Bureau of Historical Preservation,” which includes a collection from the Warsaw ghetto. But then he gets trapped in the man’s underground bunker … and Orr has writer’s block, so leaves him there. Even though it’s fiction (within fiction), I still found that unspeakably creepy.

For long stretches of the novel, Orr is lost in his notebook (“I was there, fully engaged in what was happening, and at the same time I wasn’t there—for the there wasn’t an authentic there anymore”), writing in short, obsessive bursts. In one project, a mystery inspired by an incident from The Maltese Falcon, Nick Bowen, a New York City editor, has a manuscript called Oracle Night land on his desk. Spooked by a near-death experience, he flees to Kansas City, where he gets a job working on a cabdriver’s phone book archive, “The Bureau of Historical Preservation,” which includes a collection from the Warsaw ghetto. But then he gets trapped in the man’s underground bunker … and Orr has writer’s block, so leaves him there. Even though it’s fiction (within fiction), I still found that unspeakably creepy.

In the real world, Orr’s life accumulates all sorts of complications over just nine September days. Some of them are to do with Grace and her relationship with Trause’s family; some of them concern his work. There’s a sense in which what he writes is prescient. “Maybe that’s what writing is all about, Sid,” Trause suggests. “Not recording events from the past, but making things happen in the future.” The novel has the noir air I’ve come to expect from Auster, while the layering of stories and the hints of the unexplained reminded me of Italo Calvino and Haruki Murakami. I even caught a whiff of What I Loved, the novel Auster’s wife Siri Hustvedt published the same year. (It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve spotted similar themes in husband‒wife duos’ work – cf. Jonathan Safran Foer and Nicole Krauss; Zadie Smith and Nick Laird.)

This is a carefully constructed and satisfying novel, and the works within the work are so absorbing that you as the reader get almost as lost in them as Orr himself does. I’d rank this at the top of the Auster fiction I’ve read so far, followed closely by City of Glass.

Report from the Interior (2013)

This sequel to Winter Journal came out a year later. Again, the autobiographical rendering features second-person narration and a fragmentary style. I had a ‘been there, done that’ feeling about the book and only gave it a quick skim. It might be one to try another time.

In the first 100-page section Auster highlights key moments from the inner life of a child. For instance, he remembers that the epiphany that a writer can inhabit another mind came while reading Robert Louis Stevenson’s poetry, and he emulated RLS in his own first poetic attempts. The history and pop culture of the 1950s, understanding that he was Jewish, and reaping the creative rewards of boredom are other themes. I especially liked a final anecdote about smashing his seventh-grade teacher’s reading challenge and being driven to tears when the man disbelieved that he’d read so many books and accused him of cheating.

In the first 100-page section Auster highlights key moments from the inner life of a child. For instance, he remembers that the epiphany that a writer can inhabit another mind came while reading Robert Louis Stevenson’s poetry, and he emulated RLS in his own first poetic attempts. The history and pop culture of the 1950s, understanding that he was Jewish, and reaping the creative rewards of boredom are other themes. I especially liked a final anecdote about smashing his seventh-grade teacher’s reading challenge and being driven to tears when the man disbelieved that he’d read so many books and accused him of cheating.

Other sections give long commentary on two films (something he also does in Winter Journal with 10 pages on the 1950 film D.O.A.), select from letters he wrote to his first wife in the late 1960s while living in Paris, and collect an album of black-and-white period images such as ads, film stills and newspaper photographs. There’s a strong nostalgia element, such that the memoir would appeal to Auster’s contemporaries and those interested in learning about growing up in the 1950s.

Ultimately, though, this feels unnecessary after Winter Journal. Auster repeats a circular aphorism he wrote at age 20: “The world is in my head. My body is in the world. You will stand by that paradox, which was an attempt to capture the strange doubleness of being alive, the inexorable union of inner and outer”. But I’m not sure that body and mind can be so tidily separated as these two works posit. I got more of an overall sense of Auster’s character from the previous book, even though it was ostensibly focused on his physical existence.

The library at the university where my husband works holds another four Auster novels, but I’ll wait until next year to dive back into his work. After reading other people’s reviews, I’m now most keen to try The Brooklyn Follies, Invisible and In the Country of Last Things.

Have you tried anything by Paul Auster this week?

Most Anticipated Releases for the Second Half of 2017

Back in December I previewed some of the books set to be released in 2017 that I was most excited about. Out of those 30 titles, here’s how I fared:

- Read: 16 [Disappointments: 2]

- Currently reading: 1

- Abandoned partway through: 2

- Lost interest in: 4

- Haven’t managed to find yet: 2

- Languishing on my Kindle; I still have vague intentions to read: 5

The latter half of the year promises plenty of big-name releases, such as long-awaited novels from Nicole Krauss and Jennifer Egan and a memoir by Maggie O’Farrell. Here are 24 books that happen to be on my radar for the coming months; this is by no means a full picture.

The descriptions below are adapted from the publisher blurbs on Goodreads, NetGalley or Amazon. Some of these books I already have access to in print or galley form; others I’ll be looking to get hold of. (In chronological order, generally by first publication date.)

July

How Saints Die by Carmen Marcus [July 13, Harvill Secker]: “Ten years old and irrepressibly curious, Ellie lives with her fisherman father, Peter, on the wild North Yorkshire coast. This vivacious and deeply moving novel portrays adult breakdown through the eyes of a child and celebrates the power of stories to shape, nourish and even save us.”

Moving Kings by Joshua Cohen [July 20, Fitzcarraldo Editions]: “Two young Israeli soldiers travel to New York after fighting in the Gaza War and find work as eviction movers. It’s a story of the housing and eviction crisis in poor Black and Hispanic neighborhoods that also shines new light on the world’s oldest conflict in the Middle East.” (print ARC)

August

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang [Aug. 1, Lenny]: “Centered on a community of immigrants who have traded their endangered lives as artists in China and Taiwan for the constant struggle of life at the poverty line in 1990s New York City, Zhang’s exhilarating collection examines the many ways that family and history can weigh us down and also lift us up.”

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang [Aug. 1, Lenny]: “Centered on a community of immigrants who have traded their endangered lives as artists in China and Taiwan for the constant struggle of life at the poverty line in 1990s New York City, Zhang’s exhilarating collection examines the many ways that family and history can weigh us down and also lift us up.”

The Education of a Coroner: Lessons in Investigating Death by John Bateson [Aug. 15, Scribner]: “An account of the hair-raising and heartbreaking cases handled by the coroner of Marin County, California throughout his four decades on the job—from high-profile deaths to serial killers, to Golden Gate Bridge suicides.”

The Futilitarians: Our Year of Thinking, Drinking, Grieving, and Reading by Anne Gisleson [Aug. 22, Little, Brown and Company]: “A memoir of friendship and literature chronicling a search for meaning and comfort in great books, and a beautiful path out of grief.” (currently reading via NetGalley)

Midwinter Break by Bernard McLaverty [Aug. 22, W. W. Norton]: “A retired couple fly from their home in Scotland to Amsterdam for a long weekend. … [A] tender, intimate, heart-rending story … a profound examination of human love and how we live together, a chamber piece of real resonance and power.” (to review for BookBrowse)

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell [Aug. 22, Tinder Press]: “A childhood illness she was not expected to survive. A terrifying encounter on a remote path. A mismanaged labor in an understaffed hospital … 17 encounters at different ages, in different locations, reveal to us a whole life in a series of tense, visceral snapshots.”

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell [Aug. 22, Tinder Press]: “A childhood illness she was not expected to survive. A terrifying encounter on a remote path. A mismanaged labor in an understaffed hospital … 17 encounters at different ages, in different locations, reveal to us a whole life in a series of tense, visceral snapshots.”

What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah [Aug. 24, Tinder Press]: “A dazzlingly accomplished debut collection explores the ties that bind parents and children, husbands and wives, lovers and friends to one another and to the places they call home.” (print ARC to review for Shiny New Books)

Madness Is Better than Defeat by Ned Beauman [Aug. 24, Sceptre]: “In 1938, rival expeditions set off for a lost Mayan temple, one intending to shoot a screwball comedy on location, the other to disassemble the temple and ship it to New York. … Showcasing the anarchic humor and boundless imagination of one of the finest writers of his generation.”

Forest Dark by Nicole Krauss [Aug. 24, Harper/Bloomsbury]: “A man in his later years and a woman novelist, each drawn to the Levant on a journey of self-discovery. Bursting with life and humor, this is a profound, mesmerizing novel of metamorphosis and self-realization – of looking beyond all that is visible towards the infinite.” (currently reading via NetGalley)

My Absolute Darling by Gabriel Tallent [Aug. 29, Riverhead Books/4th Estate] “A brilliant and immersive, all-consuming read about one fourteen-year-old girl’s heart-stopping fight for her own soul. … Shot through with striking language in a fierce natural setting.” (e-ARC to review for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

My Absolute Darling by Gabriel Tallent [Aug. 29, Riverhead Books/4th Estate] “A brilliant and immersive, all-consuming read about one fourteen-year-old girl’s heart-stopping fight for her own soul. … Shot through with striking language in a fierce natural setting.” (e-ARC to review for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

September

Dinner at the Center of the Earth by Nathan Englander [Sept. 5, Knopf]: “[A] political thriller that unfolds in the highly charged territory of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and pivots on the complex relationship between a secret prisoner and his guard. … Englander has woven a powerful, intensely suspenseful portrait of a nation riven by insoluble conflict.”

George and Lizzie by Nancy Pearl [Sept. 5, Touchstone]: “[A]n emotionally riveting debut novel about an unlikely marriage at a crossroads. … With pitch-perfect prose and compassion and humor to spare, George and Lizzie is an intimate story of new and past loves, the scars of childhood, and an imperfect marriage at its defining moments.”

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng [Sept. 7, Little, Brown]: “In Shaker Heights, a placid, progressive suburb of Cleveland, everything is meticulously planned. … [E]xplores the weight of long-held secrets and the ferocious pull of motherhood-and the danger of believing that planning and following the rules can avert disaster, or heartbreak.”

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng [Sept. 7, Little, Brown]: “In Shaker Heights, a placid, progressive suburb of Cleveland, everything is meticulously planned. … [E]xplores the weight of long-held secrets and the ferocious pull of motherhood-and the danger of believing that planning and following the rules can avert disaster, or heartbreak.”

Afterglow (A Dog Memoir) by Eileen Myles [Sept. 12, Grove Press]: “A probing investigation into the dynamics between pet and pet-owner. Through this lens, we examine Myles’s experiences with intimacy and spirituality, celebrity and politics, alcoholism and recovery, fathers and family history.”

October

From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death by Caitlin Doughty [Oct. 3, W. W. Norton]: “Fascinated by our pervasive terror of dead bodies, mortician Caitlin Doughty set out to discover how other cultures care for their dead. Featuring Gorey-esque illustrations by artist Landis Blair.”

Manhattan Beach by Jennifer Egan [Oct. 3, Scribner/Corsair]: “The pace and atmosphere of a noir thriller and a wealth of detail about organized crime … Egan’s first historical novel is a masterpiece, a deft, startling, intimate exploration of a transformative moment in the lives of women and men, America, and the world.”

Dunbar by Edward St. Aubyn [Oct. 3, Hogarth Shakespeare]: “Henry Dunbar, once all-powerful head of a family firm, has handed it over to his two eldest daughters, Abby and Megan. Relations quickly soured. Now imprisoned in a Lake District care home with only an alcoholic comedian as company, Dunbar starts planning his escape.” (print ARC)

The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell [Oct. 5, Profile Books]: “Bythell owns The Bookshop, Wigtown – Scotland’s largest second-hand bookshop. … These wry and hilarious diaries provide an inside look at the trials and tribulations of life in the book trade, from struggles with eccentric customers to wrangles with his own staff.”

The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell [Oct. 5, Profile Books]: “Bythell owns The Bookshop, Wigtown – Scotland’s largest second-hand bookshop. … These wry and hilarious diaries provide an inside look at the trials and tribulations of life in the book trade, from struggles with eccentric customers to wrangles with his own staff.”

In Shock by Rana Awdish [Oct. 17, St. Martin’s]: “Dr. Awdish spent months fighting for her life, enduring consecutive major surgeries and experiencing multiple overlapping organ failures. At each step of the recovery process, she was faced with repeated cavalier behavior from her fellow physicians. … A brave road map for anyone navigating illness.”

American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West by Nate Blakeslee [Oct. 17, Crown]: “[I]n recent decades, conservationists have brought wolves back to the Rockies, igniting a battle over the very soul of the West. With novelistic detail, Nate Blakeslee tells the gripping story of one of these wolves, alpha female O-Six.” (print ARC)

November

The White Book by Han Kang [Nov. 2, Portobello Books]: “Writing while on a residency in Warsaw, the narrator finds herself haunted by the story of her older sister, who died a mere two hours after birth. A fragmented exploration of white things … the most autobiographical and experimental book to date from [the] South Korean master.”

Radio Free Vermont: A Fable of Resistance by Bill McKibben [Nov. 7, Blue Rider Press]: “Follows a band of Vermont patriots who decide that their state might be better off as its own republic. … McKibben imagines an eccentric group of activists who carry out their own version of guerrilla warfare … a fictional response to the burgeoning resistance movement.”

Radio Free Vermont: A Fable of Resistance by Bill McKibben [Nov. 7, Blue Rider Press]: “Follows a band of Vermont patriots who decide that their state might be better off as its own republic. … McKibben imagines an eccentric group of activists who carry out their own version of guerrilla warfare … a fictional response to the burgeoning resistance movement.”

Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich [Nov. 14, Harper]: “Evolution has reversed itself, affecting every living creature on earth. … A chilling dystopian novel both provocative and prescient … a moving meditation on female agency, self-determination, biology, and natural rights that speaks to the troubling changes of our time.”

December

(Nothing as of yet…)

Which of these tempt you? What other books from the latter half of 2017 are you most looking forward to?

Literary Power Couples: An Inventory

With Valentine’s Day on the way, I’ve been reading a bunch of books with “Love” in the title to round up in a mini-reviews post next week. One of them was What I Loved by Siri Hustvedt – my second taste of her brilliant fiction after The Blazing World. Yet I’ve not tried a one of her husband Paul Auster’s books. There’s no particular reason for that; I’ve even had his New York Trilogy out from the library in the past, but never got around to reading it.

How about some other literary power couples? Here’s some that came to mind, along with an inventory of what I’ve read from each half. It’s pretty even for the first two couples, but in most of the other cases there’s a clear winner.

Zadie Smith: 5

Nick Laird: 5 (= ALL)

Zadie Smith in 2011. By David Shankbone (CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve read all of Zadie Smith’s work apart from NW; I only got a few pages into it when it first came out, but I’m determined to try again someday. To my surprise, I’ve read everything her husband Nick Laird has ever published, which includes three poetry collections and two fairly undistinguished ‘lad lit’ novels. I’m pleased to see that his new novel Modern Gods, coming out on June 27th, is about two sisters and looks like a stab at proper literary fiction.

Jonathan Safran Foer: 4 (= ALL)

Nicole Krauss: 3 (= ALL)

Alas, they’re now an ex-couple. In any case, they’re both on the fairly short list of authors I’d read anything by. Foer has published three novels and the nonfiction polemic Eating Animals. Krauss, too, has three novels to her name, but a new one is long overdue after the slight disappointment of 2010’s Great House.

Margaret Drabble: 5

Michael Holroyd: 0

Michael Holroyd is a biographer and general nonfiction dabbler. I have a few of his books on my TBR but don’t feel much compulsion to seek them out. By contrast, I’ve read four novels and a memoir by Margaret Drabble and am likely to devour more of her fiction in the future.

Margaret Drabble in 2011. By summonedbyfells [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)%5D via Wikimedia Commons.

Claire Tomalin: 2

Michael Frayn: 1

Claire Tomalin’s masterful biographies of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy are pillars of my nonfiction collection, and I have her books on Nelly Ternan and Samuel Pepys on the shelf to read as well. From her husband, celebrated playwright Michael Frayn, however, I’ve only read the comic novel Skios. It is very funny indeed, though, about a case of mistaken identity at an academic conference on a Greek island.

Plus a few I only recently found out about:

Ian McEwan: 7 (+ an 8th in progress)

Annalena McAfee: 1 (I’ll be reviewing her novel Hame here on Thursday)

Katie Kitamura: 1 (I just finished A Separation yesterday)

Hari Kunzru: 0

Madeleine Thien: 1 (Do Not Say We Have Nothing)

Rawi Hage: 0

Afterwards I consulted the lists of literary power couples on Flavorwire and The Huffington Post and came up with a few more that had slipped my mind:

Michael Chabon: 1

Ayelet Waldman: 0

I loved Moonglow and am keen to try Michael Chabon’s other novels, but I also have a couple of his wife Ayelet Waldman’s books on my TBR.

Dave Eggers: 5

Vendela Vida: 0

I’ve read a decent proportion of Dave Eggers’s books, fiction and nonfiction, but don’t know anything by his wife and The Believer co-founder Vendela Vida.

David Foster Wallace: 2

Mary Karr: 1

I didn’t even know they were briefly a couple. From Wallace I’ve read the essay collection Consider the Lobster and the commencement address This Is Water. I’ve definitely got to get hold of Karr’s memoirs, having so far only read her book about memoir (The Art of Memoir).

And some classics:

Ted Hughes: 1 (Crow)

Sylvia Plath: 0

F. Scott Fitzgerald: 2 (The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night)

Zelda Fitzgerald: 0

![F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald in 1921. By Kenneth Melvin Wright (Minnesota Historical Society) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://bookishbeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/f_scott_fitzgerald_and_wife_zelda_september_1921.jpg?w=208&h=300)

F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald in 1921. By Kenneth Melvin Wright (Minnesota Historical Society) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

How have you fared with these or other literary power couples? Do you generally gravitate towards one or the other from a pair?

Six Books that Disappointed Me Recently

I had high hopes for all of these: long-awaited novels from Jonathan Safran Foer (10 years after his previous one), Maria Semple and Zadie Smith; a Project Gutenberg download from the reliably funny Jerome K. Jerome; a brand new psychological thriller from James Lasdun, whose memoir and poetry I’ve loved; and a horse racing epic that generated Great American Novel buzz. But they all failed to live up to expectations.

Here I Am

By Jonathan Safran Foer

Is it a simple account of the implosion of two Washington, D.C. fortysomethings’ marriage? Or is it a sweeping epic of Judaism from the biblical patriarchs to imagined all-out Middle Eastern warfare? Can it succeed in being both? I didn’t really think so. The dialogue between this couple as they face the fallout is all too real and cuts to the quick. I enjoyed the preparations for Sam’s bar mitzvah and I could admire Julia’s clear-eyed capability and Sam, Max and Benjy’s almost alarming intelligence and heart at the same time as I wondered to what extent she was Foer’s ex-wife Nicole Krauss and they were the authors’ kids. But about halfway through I thought the book got away from Foer, requiring him to throw in a death, a natural disaster, and a conflict with global implications. This feels more like a novel by Philip Roth or Howard Jacobson, what with frequent masturbation and sex talk on the one hand and constant quarreling about what Jewishness means on the other. The central message about being present for others’ suffering, and your own, got a little lost under the flood of events.

Is it a simple account of the implosion of two Washington, D.C. fortysomethings’ marriage? Or is it a sweeping epic of Judaism from the biblical patriarchs to imagined all-out Middle Eastern warfare? Can it succeed in being both? I didn’t really think so. The dialogue between this couple as they face the fallout is all too real and cuts to the quick. I enjoyed the preparations for Sam’s bar mitzvah and I could admire Julia’s clear-eyed capability and Sam, Max and Benjy’s almost alarming intelligence and heart at the same time as I wondered to what extent she was Foer’s ex-wife Nicole Krauss and they were the authors’ kids. But about halfway through I thought the book got away from Foer, requiring him to throw in a death, a natural disaster, and a conflict with global implications. This feels more like a novel by Philip Roth or Howard Jacobson, what with frequent masturbation and sex talk on the one hand and constant quarreling about what Jewishness means on the other. The central message about being present for others’ suffering, and your own, got a little lost under the flood of events.

My rating:

Three Men on the Bummel

By Jerome K. Jerome

By Jerome K. Jerome

Jerome’s digressive style can be amusing in small doses, but this book is almost nothing but asides. I did enjoy the parts that most closely resemble a travelogue of the cycle trip through Germany, but these are drowned under a bunch of irrelevant memories and anecdotes. I much preferred Diary of a Pilgrimage.

My rating:

The Fall Guy

By James Lasdun

This is a capable psychological thriller about an out-of-work chef who becomes obsessed with the idea that his wealthy cousin’s alluring wife is cheating on him during a summer spent with them in their upstate New York bolthole. I liked hearing about Matthew’s cooking and Chloe’s photography, and it’s interesting how Lasdun draws in a bit about banking and the Occupy movement. However, the complicated Anglo-American family backstory between Matthew and Charlie feels belabored, and the fact that we only see things from Matthew’s perspective is limiting in a bad way. There’s a decent Hitchcock vibe in places, but overall this is somewhat lackluster.

This is a capable psychological thriller about an out-of-work chef who becomes obsessed with the idea that his wealthy cousin’s alluring wife is cheating on him during a summer spent with them in their upstate New York bolthole. I liked hearing about Matthew’s cooking and Chloe’s photography, and it’s interesting how Lasdun draws in a bit about banking and the Occupy movement. However, the complicated Anglo-American family backstory between Matthew and Charlie feels belabored, and the fact that we only see things from Matthew’s perspective is limiting in a bad way. There’s a decent Hitchcock vibe in places, but overall this is somewhat lackluster.

My rating:

The Sport of Kings

By C.E. Morgan

I found this Kentucky-based horse racing novel to be florid and overlong. The novel doesn’t achieve takeoff until Allmon comes on the scene at about page 180. Although there are good descriptions of horses, the main plot – training Hellsmouth to compete in the 2006 Derby – mostly passed me by. Meanwhile, the interpersonal relationships become surprisingly melodramatic, more fit for a late Victorian novel or maybe something by Faulkner. My favorite character was Maryleen, the no-nonsense black house servant. Henry himself, though, makes for pretty unpleasant company. Morgan delivers the occasional great one-liner (“Childhood is the country of question marks, and the streets are solid answers”), but her prose is on the whole incredibly overwritten. There’s a potent message in here somewhere about ambition, inheritance and race, but it’s buried under an overwhelming weight of words. (See my full Nudge review.)

I found this Kentucky-based horse racing novel to be florid and overlong. The novel doesn’t achieve takeoff until Allmon comes on the scene at about page 180. Although there are good descriptions of horses, the main plot – training Hellsmouth to compete in the 2006 Derby – mostly passed me by. Meanwhile, the interpersonal relationships become surprisingly melodramatic, more fit for a late Victorian novel or maybe something by Faulkner. My favorite character was Maryleen, the no-nonsense black house servant. Henry himself, though, makes for pretty unpleasant company. Morgan delivers the occasional great one-liner (“Childhood is the country of question marks, and the streets are solid answers”), but her prose is on the whole incredibly overwritten. There’s a potent message in here somewhere about ambition, inheritance and race, but it’s buried under an overwhelming weight of words. (See my full Nudge review.)

My rating:

Today Will Be Different

By Maria Semple

Bernadette fans, prepare for disappointment. There’s nothing that bad about the story of middle-aged animator Eleanor Flood, her hand-surgeon-to-the-stars husband Joe, and their precocious kid Timby, but nor is there anything very interesting about it. The novel is one of those rare ones that take place all in one day, a setup that enticed me, but all Eleanor manages to fit into her day – despite the title resolution – is an encounter with a pet poet who listens to her reciting memorized verse, another with a disgruntled former employee, some pondering of her husband’s strange behavior, and plenty of being downright mean to her son (as if his name wasn’t punishment enough). “In the past, I’d often been called crazy. But it was endearing-crazy, kooky-crazy, we’re-all-a-little-crazy-crazy,” Eleanor insists. I didn’t think so. I didn’t like being stuck in her head. In general, it seems like a bad sign if you’re eager to get away from a book’s narrator and her scatty behavior. Compared to Semple’s previous novel, it feels like quirkiness for quirkiness’ sake, with a sudden, contrived ending.

Bernadette fans, prepare for disappointment. There’s nothing that bad about the story of middle-aged animator Eleanor Flood, her hand-surgeon-to-the-stars husband Joe, and their precocious kid Timby, but nor is there anything very interesting about it. The novel is one of those rare ones that take place all in one day, a setup that enticed me, but all Eleanor manages to fit into her day – despite the title resolution – is an encounter with a pet poet who listens to her reciting memorized verse, another with a disgruntled former employee, some pondering of her husband’s strange behavior, and plenty of being downright mean to her son (as if his name wasn’t punishment enough). “In the past, I’d often been called crazy. But it was endearing-crazy, kooky-crazy, we’re-all-a-little-crazy-crazy,” Eleanor insists. I didn’t think so. I didn’t like being stuck in her head. In general, it seems like a bad sign if you’re eager to get away from a book’s narrator and her scatty behavior. Compared to Semple’s previous novel, it feels like quirkiness for quirkiness’ sake, with a sudden, contrived ending.

My rating:

Swing Time

By Zadie Smith

Smith’s fifth novel spans 25 years and journeys from London to New York City and West Africa in tracing the different paths two black girls’ lives take. The narrator (who is never named) and Tracey, both biracial, meet through dance lessons at age seven in 1982 and soon become inseparable. The way this relationship shifts over time is the most potent element of the novel, and will appeal to fans of Elena Ferrante. The narrator alternates chapters about her friendship with Tracey with chapters about her work for pop star Aimee in Africa. Unfortunately, the Africa material is not very convincing or lively and I was impatient for these sections to finish. The Aimee subplot and the way Tracey turns out struck me as equally clichéd. Despite the geographical and chronological sprawl, the claustrophobic narration makes this feel insular, defusing its potential messages about how race, money and class still define and divide us. A new Zadie Smith novel is an event; this one is still worth reading, but it definitely disappointed me in comparison to White Teeth and On Beauty. (Releases Nov. 15th.)

Smith’s fifth novel spans 25 years and journeys from London to New York City and West Africa in tracing the different paths two black girls’ lives take. The narrator (who is never named) and Tracey, both biracial, meet through dance lessons at age seven in 1982 and soon become inseparable. The way this relationship shifts over time is the most potent element of the novel, and will appeal to fans of Elena Ferrante. The narrator alternates chapters about her friendship with Tracey with chapters about her work for pop star Aimee in Africa. Unfortunately, the Africa material is not very convincing or lively and I was impatient for these sections to finish. The Aimee subplot and the way Tracey turns out struck me as equally clichéd. Despite the geographical and chronological sprawl, the claustrophobic narration makes this feel insular, defusing its potential messages about how race, money and class still define and divide us. A new Zadie Smith novel is an event; this one is still worth reading, but it definitely disappointed me in comparison to White Teeth and On Beauty. (Releases Nov. 15th.)

My rating:

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African-American twins’ paths divide in 1950s Louisiana. Perceptive and beautifully written, this has characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African-American twins’ paths divide in 1950s Louisiana. Perceptive and beautifully written, this has characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent. Piranesi by Susanna Clarke: To start with, Piranesi traverses his watery labyrinth like he’s an eighteenth-century adventurer, his resulting notebooks reading rather like Alexander von Humboldt’s writing. I admired how the novel moved from the fantastical and abstract into the real and gritty. Read it even if you say you don’t like fantasy.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke: To start with, Piranesi traverses his watery labyrinth like he’s an eighteenth-century adventurer, his resulting notebooks reading rather like Alexander von Humboldt’s writing. I admired how the novel moved from the fantastical and abstract into the real and gritty. Read it even if you say you don’t like fantasy. Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan: At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens and almost accidentally embarks on affairs with an English guy and a Chinese girl. Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners.

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan: At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens and almost accidentally embarks on affairs with an English guy and a Chinese girl. Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners. *A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: Issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance in a perfect-seeming North Carolina community. This is narrated in a first-person plural voice, like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved An American Marriage, it should be next on your list. I’m puzzled by how overlooked it’s been this year.

*A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: Issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance in a perfect-seeming North Carolina community. This is narrated in a first-person plural voice, like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved An American Marriage, it should be next on your list. I’m puzzled by how overlooked it’s been this year. Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi: A more subdued and subtle book than Homegoing, but its treatment of themes of addiction, grief, racism, and religion is so spot on that it packs a punch. Gifty is a PhD student at Stanford, researching reward circuits in the mouse brain. There’s also a complex mother–daughter relationship and musings on love and risk. [To be published in the UK in March]

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi: A more subdued and subtle book than Homegoing, but its treatment of themes of addiction, grief, racism, and religion is so spot on that it packs a punch. Gifty is a PhD student at Stanford, researching reward circuits in the mouse brain. There’s also a complex mother–daughter relationship and musings on love and risk. [To be published in the UK in March] The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave: A rich, natural exploration of a place and time period – full of detail but wearing its research lightly. Inspired by a real-life storm that struck on Christmas Eve 1617 and wiped out the male population of the Norwegian island of Vardø, it intimately portrays the lives of the women left behind. Tender, surprising, and harrowing.

The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave: A rich, natural exploration of a place and time period – full of detail but wearing its research lightly. Inspired by a real-life storm that struck on Christmas Eve 1617 and wiped out the male population of the Norwegian island of Vardø, it intimately portrays the lives of the women left behind. Tender, surprising, and harrowing. Sisters by Daisy Johnson: Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. For much of this short novel, Johnson keeps readers guessing as to why the girls’ mother, Sheela, took them away to Settle House, her late husband’s family home in the North York Moors. As mesmerizing as it is unsettling.

Sisters by Daisy Johnson: Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. For much of this short novel, Johnson keeps readers guessing as to why the girls’ mother, Sheela, took them away to Settle House, her late husband’s family home in the North York Moors. As mesmerizing as it is unsettling. The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd: Kidd’s bold fourth novel started as a what-if question: What if Jesus had a wife? Although this retells biblical events, it is chiefly an attempt to illuminate women’s lives in the 1st century and to chart the female contribution to sacred literature and spirituality. An engrossing story of women’s intuition and yearning.

The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd: Kidd’s bold fourth novel started as a what-if question: What if Jesus had a wife? Although this retells biblical events, it is chiefly an attempt to illuminate women’s lives in the 1st century and to chart the female contribution to sacred literature and spirituality. An engrossing story of women’s intuition and yearning. *The Ninth Child by Sally Magnusson: Intense and convincing, this balances historical realism and magical elements. In mid-1850s Scotland, there is a move to ensure clean water. The Glasgow waterworks’ physician’s wife meets a strange minister who died in 1692. A rollicking read with medical elements and a novel look into Victorian women’s lives.

*The Ninth Child by Sally Magnusson: Intense and convincing, this balances historical realism and magical elements. In mid-1850s Scotland, there is a move to ensure clean water. The Glasgow waterworks’ physician’s wife meets a strange minister who died in 1692. A rollicking read with medical elements and a novel look into Victorian women’s lives. *The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting: In this first book of a magic-fueled historical trilogy, progress, religion, and superstition are forces fighting for the soul of a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian village. Mytting constructs the novel around compelling dichotomies. Astrid, a feminist ahead of her time, vows to protect the ancestral church bells.

*The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting: In this first book of a magic-fueled historical trilogy, progress, religion, and superstition are forces fighting for the soul of a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian village. Mytting constructs the novel around compelling dichotomies. Astrid, a feminist ahead of her time, vows to protect the ancestral church bells. What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is called upon to help a terminally ill friend commit suicide. The voice is not solely or even primarily the narrator’s but Other: art consumed and people encountered become part of her own story; curiosity about other lives fuels empathy. A quiet novel that sneaks up to seize you by the heartstrings.

What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is called upon to help a terminally ill friend commit suicide. The voice is not solely or even primarily the narrator’s but Other: art consumed and people encountered become part of her own story; curiosity about other lives fuels empathy. A quiet novel that sneaks up to seize you by the heartstrings. Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, written in an aphoristic style. Set either side of Trump’s election in 2016, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are dead right. This felt like a perfect book for 2020 and its worries.

Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, written in an aphoristic style. Set either side of Trump’s election in 2016, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are dead right. This felt like a perfect book for 2020 and its worries. Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward: An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. I was particularly taken by the chapter narrated by the ant. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward: An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. I was particularly taken by the chapter narrated by the ant. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one. *The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Against a backdrop of flooding and bush fires, a series of personal catastrophes play out. A timely, quietly forceful story of how women cope with concrete and existential threats.

*The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Against a backdrop of flooding and bush fires, a series of personal catastrophes play out. A timely, quietly forceful story of how women cope with concrete and existential threats. To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss: These 10 stories from the last 18 years are melancholy and complex, often featuring several layers of Jewish family history. Europe, Israel, and film are frequent points of reference. “Future Emergencies,” though set just after 9/11, ended up feeling the most contemporary because it involves gas masks and other disaster preparations.

To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss: These 10 stories from the last 18 years are melancholy and complex, often featuring several layers of Jewish family history. Europe, Israel, and film are frequent points of reference. “Future Emergencies,” though set just after 9/11, ended up feeling the most contemporary because it involves gas masks and other disaster preparations. *Help Yourself by Curtis Sittenfeld: A bonus second UK release from Sittenfeld in 2020 after Rodham. Just three stories, but not leftovers; a strong follow-up to You Think It, I’ll Say It. They share the theme of figuring out who you really are versus what others think of you. “White Women LOL,” especially, compares favorably to Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age.

*Help Yourself by Curtis Sittenfeld: A bonus second UK release from Sittenfeld in 2020 after Rodham. Just three stories, but not leftovers; a strong follow-up to You Think It, I’ll Say It. They share the theme of figuring out who you really are versus what others think of you. “White Women LOL,” especially, compares favorably to Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age. You Will Never Be Forgotten by Mary South: In this debut collection, characters turn to technology to stake a claim on originality, compensate for losses, and leave a legacy. These 10 quirky, humorous stories never strayed so far into science fiction as to alienate me. I loved the medical themes and subtle, incisive observations about a technology-obsessed culture.

You Will Never Be Forgotten by Mary South: In this debut collection, characters turn to technology to stake a claim on originality, compensate for losses, and leave a legacy. These 10 quirky, humorous stories never strayed so far into science fiction as to alienate me. I loved the medical themes and subtle, incisive observations about a technology-obsessed culture. *Survival Is a Style by Christian Wiman: Wiman examines Christian faith in the shadow of cancer. This is the third of his books that I’ve read, and I’m consistently impressed by how he makes room for doubt, bitterness, and irony – yet a flame of faith remains. There is really interesting phrasing and vocabulary in this volume.

*Survival Is a Style by Christian Wiman: Wiman examines Christian faith in the shadow of cancer. This is the third of his books that I’ve read, and I’m consistently impressed by how he makes room for doubt, bitterness, and irony – yet a flame of faith remains. There is really interesting phrasing and vocabulary in this volume. Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho: Cho experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She alternates between her time in the mental hospital and her life before the breakdown, weaving in family history and Korean sayings and legends. It’s a painstakingly vivid account.

Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho: Cho experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She alternates between her time in the mental hospital and her life before the breakdown, weaving in family history and Korean sayings and legends. It’s a painstakingly vivid account. *The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: DNA tests can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction.

*The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: DNA tests can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction. *Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes: Fabes is an emergency room doctor in London and spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents. This warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of his travels achieves a perfect balance between world events, everyday discomforts, and humanitarian volunteering.

*Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes: Fabes is an emergency room doctor in London and spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents. This warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of his travels achieves a perfect balance between world events, everyday discomforts, and humanitarian volunteering. Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: Nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, but Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming in lots of information yet never losing sight of the big picture.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: Nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, but Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming in lots of information yet never losing sight of the big picture. *Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb: Jewish grandmothers are renowned for their fiercely protective love, but also for nagging. Both sides of the stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny, heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother. A real delight.

*Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb: Jewish grandmothers are renowned for their fiercely protective love, but also for nagging. Both sides of the stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny, heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother. A real delight. Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is a leader in the UK’s youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year and the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism.

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is a leader in the UK’s youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year and the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism. Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey: Trethewey grew up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, then moved with her mother to Atlanta. Her stepfather was abusive; her mother’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to their Memorial Drive apartment after 30 years had passed. A striking memoir, delicate and painful.

Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey: Trethewey grew up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, then moved with her mother to Atlanta. Her stepfather was abusive; her mother’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to their Memorial Drive apartment after 30 years had passed. A striking memoir, delicate and painful.

One for angsty, bookish types. In 2012 Anne Gisleson, a New Orleans-based creative writing teacher, her husband, sister and some friends formed an Existential Crisis Reading Group (which, for the record, I think would have been a better title). Each month they got together to discuss their lives and their set readings – both expected and off-beat selections, everything from Kafka and Tolstoy to Kingsley Amis and Clarice Lispector – over wine and snacks.

One for angsty, bookish types. In 2012 Anne Gisleson, a New Orleans-based creative writing teacher, her husband, sister and some friends formed an Existential Crisis Reading Group (which, for the record, I think would have been a better title). Each month they got together to discuss their lives and their set readings – both expected and off-beat selections, everything from Kafka and Tolstoy to Kingsley Amis and Clarice Lispector – over wine and snacks.

I enjoy Tom Perrotta’s novels: they’re funny, snappy, current and relatable; it’s no surprise they make great movies. I’ve somehow read seven of his nine books now, without even realizing it. Mrs. Fletcher is more of the same satire on suburban angst, but with an extra layer of raunchiness that struck me as unnecessary. It seemed something like a sexual box-ticking exercise. But for all the deliberately edgy content, this book isn’t really doing anything very groundbreaking; it’s the same old story of temptations and bad decisions, but with everything basically going back to a state of normality by the end. If you haven’t read any Perrotta before and are interested in giving his work a try, let me steer you towards Little Children instead. That’s his best book by far.

I enjoy Tom Perrotta’s novels: they’re funny, snappy, current and relatable; it’s no surprise they make great movies. I’ve somehow read seven of his nine books now, without even realizing it. Mrs. Fletcher is more of the same satire on suburban angst, but with an extra layer of raunchiness that struck me as unnecessary. It seemed something like a sexual box-ticking exercise. But for all the deliberately edgy content, this book isn’t really doing anything very groundbreaking; it’s the same old story of temptations and bad decisions, but with everything basically going back to a state of normality by the end. If you haven’t read any Perrotta before and are interested in giving his work a try, let me steer you towards Little Children instead. That’s his best book by far.

I read “We Love You Crispina” (13%), about the string of awful hovels a family of Chinese immigrants is forced to move between in early 1990s New York City. You’d think it would be unbearably sad reading about cockroaches and shared mattresses and her father’s mistress, but Zhang’s deadpan litanies are actually very funny: “After Woodside we moved to another floor, this time in my mom’s cousin’s friend’s sister’s apartment in Ocean Hill that would have been perfect except for the nights when rats ran over our faces while we were sleeping and even on the nights they didn’t, we were still being charged twice the cost of a shitty motel.” Perhaps I’m out of practice in reading short story collections, but after I finished this first story I felt absolutely no need to move on to the rest of the book.

I read “We Love You Crispina” (13%), about the string of awful hovels a family of Chinese immigrants is forced to move between in early 1990s New York City. You’d think it would be unbearably sad reading about cockroaches and shared mattresses and her father’s mistress, but Zhang’s deadpan litanies are actually very funny: “After Woodside we moved to another floor, this time in my mom’s cousin’s friend’s sister’s apartment in Ocean Hill that would have been perfect except for the nights when rats ran over our faces while we were sleeping and even on the nights they didn’t, we were still being charged twice the cost of a shitty motel.” Perhaps I’m out of practice in reading short story collections, but after I finished this first story I felt absolutely no need to move on to the rest of the book. Impressive in scope and structure, but rather frustrating. If you’re hoping for another History of Love, you’re likely to come away disappointed: while that book touched the heart; this one is mostly cerebral. Metafiction, the Kabbalah, and some alternative history featuring Kafka are a few of the major elements, so think about whether those topics attract or repel you. Looking a bit deeper, this is a book about Jewish self-invention and reinvention. Now, when I read a novel with a dual narrative, especially when the two strands share a partial setting – here, the Tel Aviv Hilton – I fully expect them to meet up at some point. In Forest Dark that never happens. At least, I don’t think so.* I sometimes found “Nicole” (the author character) insufferably clever and inward-gazing. All told, there’s a lot to think about here: more questions than answers, really. Interesting, for sure, but not the return to form I’d hoped for.

Impressive in scope and structure, but rather frustrating. If you’re hoping for another History of Love, you’re likely to come away disappointed: while that book touched the heart; this one is mostly cerebral. Metafiction, the Kabbalah, and some alternative history featuring Kafka are a few of the major elements, so think about whether those topics attract or repel you. Looking a bit deeper, this is a book about Jewish self-invention and reinvention. Now, when I read a novel with a dual narrative, especially when the two strands share a partial setting – here, the Tel Aviv Hilton – I fully expect them to meet up at some point. In Forest Dark that never happens. At least, I don’t think so.* I sometimes found “Nicole” (the author character) insufferably clever and inward-gazing. All told, there’s a lot to think about here: more questions than answers, really. Interesting, for sure, but not the return to form I’d hoped for.