Women’s Prize 2021: Predictions & Eligible Titles

In previous years I’ve been a half-hearted follower of the Women’s Prize – often half or more of the longlist doesn’t interest me – but given that nearly two-thirds of my annual reading is by women, and that I so enjoyed catching up on the previous winners last year, I somehow feel more invested this year. Following literary prizes is among my greatest bookish joys, so this time round I’ve made more of an effort to look back through a year of UK fiction releases by women, whether I’ve read the books or not, and make some informed predictions.

Here is the scope of the prize: “Any woman writing in English – whatever her nationality, country of residence, age or subject matter – is eligible. Novels must be published in the United Kingdom between 1 April in the year the Prize calls for entries, and 31 March the following year, when the Prize is announced.” (Note: no novellas or short stories; the judges are looking for the best work by a woman – or a trans person legally defined as a woman.)

Based on the books by women that I have admired, loved, or found most relevant in 2020‒21, here are my predictions for the longlist, which will be revealed on March 10th (two weeks from today) and will contain 16 titles. I’ve aimed for a balance between new and established voices, and a mix of genres. I link to my reviews where available.

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

- Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

- Sisters by Daisy Johnson

- Pew by Catherine Lacey

- No One Is Talking about This by Patricia Lockwood – currently reading

- A Burning by Megha Majumdar*

- The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

- Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley**

- Outlawed by Anna North

- Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud

- The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey***

- The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams

* Not read yet. It seems like this year’s Home Fire.

** Not read yet, but I loved Elmet so much that I’m confident this will be a hit with me, too.

*** Not read yet. I plan to read it, but after its Costa win there’s a long library holds queue.

Note: “The Prize only accepts novels entered by publishers, who may each submit a maximum of two titles per imprint and one title for imprints with a list of five fiction titles or fewer published in a year. Previously shortlisted and winning authors are awarded a ‘free pass’ in addition to a publisher’s general submissions.”

- Because of all the funds the publishers are expected to contribute to the Prize’s publicity at each level of judging, the process unfairly discriminates against small, independent publishers.

Bernardine Evaristo is the chair of judges this year, so I expect a strong showing from BIPOC and LGBTQ authors AND a leaning towards experimental prose, probably even more so than my above list reflects.

Other novels I considered:

Runners-up – books that I enjoyed and would be perfectly happy to see nominated:

- Milk Fed by Melissa Broder – not reviewed yet

- Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan

- The Group by Lara Feigel

- Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller – not reviewed yet

- Artifact by Arlene Heyman

- The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd

- A Town Called Solace by Sue Lawson – not reviewed yet

- Monogamy by Sue Miller

- What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez

- Islands of Mercy by Rose Tremain

Reads that didn’t match up for me, but would be eligible:

- When the Lights Go Out by Carys Bray

- The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

- Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey

- The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney (DNF)

- The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin

- Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce

- The Animals in That Country by Laura Jean McKay

- Scenes of a Graphic Nature by Caroline O’Donoghue

- True Story by Kate Reed Petty (DNF)

- Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld

- The Lamplighters by Emma Stonex – currently reading

- Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler

- little scratch by Rebecca Watson

- Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson

Haven’t had a chance to read yet / don’t have access to, so can only list without comment (most likely alternative nominees in bold):

- Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa

- You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

- The Push by Ashley Audrain

- If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

- [The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi] – Update: would not be eligible according to the new requirement that trans people be legally defined as female; before that regulation was in place, Emezi was longlisted for Freshwater.

- Sea Wife by Amity Gaige

- The Wild Laughter by Caoilinn Hughes

- How We Are Translated by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson

- Consent by Annabel Lyon

- A Crooked Tree by Una Mannion

- The Last Migration by Charlotte McConaghy

- The Art of Falling by Danielle McLaughlin

- His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

- A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa

- Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

- Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler

- An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson – gets a “free pass” entry as MR is a previous winner

- Belladonna by Anbara Salam

- Kololo Hill by Neema Shah

- All Adults Here by Emma Straub

- Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan

- Saving Lucia by Anna Vaught

- We Are All Birds of Uganda by Hafsa Zayyan

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang

I overlapped with this Goodreads list (which I didn’t look at until after compiling mine) on 28 titles. It erroneously includes The Anthill by Julianne Pachico – not released in the UK until May 2021 – but otherwise has another nearly 50, mostly solid, ideas, such as Luster by Raven Leilani, Blue Ticket by Sophie Mackintosh, and Death in her Hands by Ottessa Moshfegh.

See also Laura’s and Rachel’s predictions.

Any predictions or wishes for the Women’s Prize longlist?

November Plans: Novellas, Margaret Atwood Reading Month & More

This is my fourth year joining Laura Frey and others in reading mostly novellas in November. Last year Laura put together a history of the challenge (here); it has had various incarnations but has no particular host or rules. Join us if you like! (#NovNov and #NovellasinNovember) The definition of a novella is loose – it’s based more on the word count than the number of pages – so it’s up to you what you’d like to classify as one. I generally limit myself to books of 150 pages or fewer, though I might go as high as 180-some if there aren’t that many words on a page. Some, including Laura and Susan, would be as generous as 200.

I’ve trawled my shelves for fiction and nonfiction stacks to select from, as well as a few volumes that include several novellas (I’d plan on reading at least the first one) and some slightly longer novels (150–190 pages) for backups. [From the N. West volume, I just have the 52-page novella The Dream Life of Balso Snell, his debut, to read. The Tangye book with the faded cover is Lama.] Also available on my Kindle are The Therapist by Nial Giacomelli*, Record of a Night too Brief by Hiromi Kawakami, Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Reve, and Milton in Purgatory by Edward Vass* (both *Fairlight Moderns Novellas, as is Atlantic Winds by William Prendiville).

Other November reading plans…

Margaret Atwood Reading Month

This is the second year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. This year they’re having a special The Handmaid’s Tale/The Testaments theme, but even if you’re avoiding the sequel, join us in reading one or more Atwood works of your choice. She has so much to choose from! Last year I read The Edible Woman and Surfacing. This year I’ve earmarked copies of the novel The Robber Bride (1993) and Moral Disorder (2006), a linked short story collection, both of which I got for free – the former from the free bookshop where I volunteer, and the latter from a neighbor who was giving it away.

This is the second year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. This year they’re having a special The Handmaid’s Tale/The Testaments theme, but even if you’re avoiding the sequel, join us in reading one or more Atwood works of your choice. She has so much to choose from! Last year I read The Edible Woman and Surfacing. This year I’ve earmarked copies of the novel The Robber Bride (1993) and Moral Disorder (2006), a linked short story collection, both of which I got for free – the former from the free bookshop where I volunteer, and the latter from a neighbor who was giving it away.

Nonfiction November

I don’t usually participate in this challenge because nonfiction makes up at least 40% of my reading anyway, but last year I enjoyed putting together some fiction and nonfiction pairings and ‘being the expert’ on women’s religious memoirs, a subgenre I have a couple of books to add to this year. So I will probably end up doing at least one post. The full schedule is here.

Young Writer of the Year Award

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times/PFD Young Writer of the Year Award was a highlight of 2017 for me. I was sad to not be able to attend any of the events last year. I’m excited for this year’s shadow panelists, a couple of whom are blogging friends (one I’ve met IRL), and I look forward to following along with the nominated books and attending the prize ceremony at the London Library on December 5th.

With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist, which is to be announced on November 3rd. I have my fingers crossed for Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Daisy Johnson, Elizabeth Macneal, Stephen Rutt and Lara Williams; I expect we may also see repeat appearances from one of the poets recognized by the Forward Prizes and Guy Gunaratne, the winner of the 2019 Dylan Thomas Prize.

With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist, which is to be announced on November 3rd. I have my fingers crossed for Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Daisy Johnson, Elizabeth Macneal, Stephen Rutt and Lara Williams; I expect we may also see repeat appearances from one of the poets recognized by the Forward Prizes and Guy Gunaratne, the winner of the 2019 Dylan Thomas Prize.

Any reading plans for November? Will you be joining in with novellas, Margaret Atwood’s books or Nonfiction November?

November Reading Plans: Novellas, Margaret Atwood and More

This is my third year joining Laura Frey and others in reading novellas in November. Laura has put together a history of the challenge here; it has had various incarnations but has no particular host or rules. Join us if you like! (#NovNov) The definition of a novella seems to be loose – it’s based more on word count than page count – so it’s up to you what you’d like to classify as one. I generally limit myself to books of 150 pages or fewer, though in some cases I’d probably go as high as 180-some. I’ve trawled my shelves and library pile and have four stacks to select from: fiction, classics, novella-length nonfiction, and slightly longer novels (160–190 pages) that I’ll keep around as backups but likely won’t get to.

Between what I have in these stacks, holds I’m waiting on at the library (West by Carys Davies, The Glorious Life of the Oak by John Lewis-Stempel and Holloway by Robert Macfarlane), and some additional choices on my e-readers (Lady into Fox by David Garnett, Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot and Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Reve), I easily have enough for a book a day. In a future year maybe I’d be able to clear my schedule such that I could indeed read one novella per day, but I have so many review books on the go that I won’t aim for that. Besides, I’m not the kind of reader who’d sit down and read a 160-page book in one sitting; I’d be more likely to read 20 pages each in eight different books.

This is the pile I’ll be starting later today. (The Evans looks long but is 164 pages of text with various full- and half-page black-and-white illustrations dotted through.)

I got a headstart on Novellas in November with this Canongate volume published today.

Courage Calls to Courage Everywhere by Jeanette Winterson

Last year it was Mary Beard’s Women and Power; in 2018 this is the Christmas gift to slip into every feminist book-lover’s stocking. Adapted from Winterson’s Richard Dimbleby Lecture and supplemented by the text of Emmeline Pankhurst’s 1913 speech “Freedom or Death,” this is a slim, attractive volume that feels timely if insubstantial. Winterson gives a potted history of suffragism and argues that female brains are not wired differently; it’s just social programming that tells us so. Gender imbalances in university admissions and the job market continued into the 1970s, so it’s no surprise, she says, that women are still catching up 40 years later – and she supports measures that could be labeled as positive discrimination.

Last year it was Mary Beard’s Women and Power; in 2018 this is the Christmas gift to slip into every feminist book-lover’s stocking. Adapted from Winterson’s Richard Dimbleby Lecture and supplemented by the text of Emmeline Pankhurst’s 1913 speech “Freedom or Death,” this is a slim, attractive volume that feels timely if insubstantial. Winterson gives a potted history of suffragism and argues that female brains are not wired differently; it’s just social programming that tells us so. Gender imbalances in university admissions and the job market continued into the 1970s, so it’s no surprise, she says, that women are still catching up 40 years later – and she supports measures that could be labeled as positive discrimination.

From the #MeToo movement she makes what seems like an odd swerve into discussing AI because computer science/Silicon Valley is very male-dominated and she wants to be sure women have a respected role in the future. My reaction to this was the same as to Beard’s book and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists: you can’t (and I don’t) dispute what the author has to say; for the most part the points are compelling and well made. Yet I don’t necessarily feel that I learned anything, or saw something familiar in a new way.

Favorite lines:

“When prejudice and bad science are no longer in the way, women always prove themselves as capable as men.”

“that’s how it is with patriarchy – we don’t notice the all-male panels, the movies where women are just the love interest, the number of male presenters on TV and radio […] and we do need parity, because women are one half of the population.”

My rating:

Other November reading plans…

Margaret Atwood Reading Month

Margaret Atwood Reading Month

One of my longer novellas is a library copy of Surfacing (1972), which will be my first of two reads for the Margaret Atwood Reading Month hosted by Marcie and Naomi. I also own a copy of The Edible Woman (1969) and look forward to trying both of these early works.

Young Writer of the Year Award

Being involved with the Sunday Times/PFD Young Writer of the Year Award was one of my highlights of 2017. I’m excited for this year’s shadow panelists, several of whom are longtime blogging friends, and look forward to following along with the shortlist reads even though I can’t attend this year’s events. With any luck I will already have read at least one or two of the nominees (fingers crossed for Daisy Johnson and Fiona Mozley) so that there’s only a couple more to discover.

John Leonard Prize committee

In May I joined the National Book Critics Circle. One of the awards they give annually is the John Leonard Prize for the best first book in any genre. The pool of nominees is based on member recommendations, and a volunteer panel of members (as many as are interested!) then reads the 5–7 finalists and votes for a winner by January 8th. I signed up to be on the panel, so I’m committed to reading all the finalists in e-book format within about six weeks. Again, I hope to find that I’ve already read at least a few of the nominees. Regardless, it will be a fun project to keep me busy over our two weeks in America for the holidays.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African-American twins’ paths divide in 1950s Louisiana. Perceptive and beautifully written, this has characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African-American twins’ paths divide in 1950s Louisiana. Perceptive and beautifully written, this has characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent. Piranesi by Susanna Clarke: To start with, Piranesi traverses his watery labyrinth like he’s an eighteenth-century adventurer, his resulting notebooks reading rather like Alexander von Humboldt’s writing. I admired how the novel moved from the fantastical and abstract into the real and gritty. Read it even if you say you don’t like fantasy.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke: To start with, Piranesi traverses his watery labyrinth like he’s an eighteenth-century adventurer, his resulting notebooks reading rather like Alexander von Humboldt’s writing. I admired how the novel moved from the fantastical and abstract into the real and gritty. Read it even if you say you don’t like fantasy. Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan: At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens and almost accidentally embarks on affairs with an English guy and a Chinese girl. Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners.

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan: At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens and almost accidentally embarks on affairs with an English guy and a Chinese girl. Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners. *A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: Issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance in a perfect-seeming North Carolina community. This is narrated in a first-person plural voice, like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved An American Marriage, it should be next on your list. I’m puzzled by how overlooked it’s been this year.

*A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: Issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance in a perfect-seeming North Carolina community. This is narrated in a first-person plural voice, like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved An American Marriage, it should be next on your list. I’m puzzled by how overlooked it’s been this year. Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi: A more subdued and subtle book than Homegoing, but its treatment of themes of addiction, grief, racism, and religion is so spot on that it packs a punch. Gifty is a PhD student at Stanford, researching reward circuits in the mouse brain. There’s also a complex mother–daughter relationship and musings on love and risk. [To be published in the UK in March]

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi: A more subdued and subtle book than Homegoing, but its treatment of themes of addiction, grief, racism, and religion is so spot on that it packs a punch. Gifty is a PhD student at Stanford, researching reward circuits in the mouse brain. There’s also a complex mother–daughter relationship and musings on love and risk. [To be published in the UK in March] The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave: A rich, natural exploration of a place and time period – full of detail but wearing its research lightly. Inspired by a real-life storm that struck on Christmas Eve 1617 and wiped out the male population of the Norwegian island of Vardø, it intimately portrays the lives of the women left behind. Tender, surprising, and harrowing.

The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave: A rich, natural exploration of a place and time period – full of detail but wearing its research lightly. Inspired by a real-life storm that struck on Christmas Eve 1617 and wiped out the male population of the Norwegian island of Vardø, it intimately portrays the lives of the women left behind. Tender, surprising, and harrowing. Sisters by Daisy Johnson: Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. For much of this short novel, Johnson keeps readers guessing as to why the girls’ mother, Sheela, took them away to Settle House, her late husband’s family home in the North York Moors. As mesmerizing as it is unsettling.

Sisters by Daisy Johnson: Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. For much of this short novel, Johnson keeps readers guessing as to why the girls’ mother, Sheela, took them away to Settle House, her late husband’s family home in the North York Moors. As mesmerizing as it is unsettling. The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd: Kidd’s bold fourth novel started as a what-if question: What if Jesus had a wife? Although this retells biblical events, it is chiefly an attempt to illuminate women’s lives in the 1st century and to chart the female contribution to sacred literature and spirituality. An engrossing story of women’s intuition and yearning.

The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd: Kidd’s bold fourth novel started as a what-if question: What if Jesus had a wife? Although this retells biblical events, it is chiefly an attempt to illuminate women’s lives in the 1st century and to chart the female contribution to sacred literature and spirituality. An engrossing story of women’s intuition and yearning. *The Ninth Child by Sally Magnusson: Intense and convincing, this balances historical realism and magical elements. In mid-1850s Scotland, there is a move to ensure clean water. The Glasgow waterworks’ physician’s wife meets a strange minister who died in 1692. A rollicking read with medical elements and a novel look into Victorian women’s lives.

*The Ninth Child by Sally Magnusson: Intense and convincing, this balances historical realism and magical elements. In mid-1850s Scotland, there is a move to ensure clean water. The Glasgow waterworks’ physician’s wife meets a strange minister who died in 1692. A rollicking read with medical elements and a novel look into Victorian women’s lives. *The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting: In this first book of a magic-fueled historical trilogy, progress, religion, and superstition are forces fighting for the soul of a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian village. Mytting constructs the novel around compelling dichotomies. Astrid, a feminist ahead of her time, vows to protect the ancestral church bells.

*The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting: In this first book of a magic-fueled historical trilogy, progress, religion, and superstition are forces fighting for the soul of a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian village. Mytting constructs the novel around compelling dichotomies. Astrid, a feminist ahead of her time, vows to protect the ancestral church bells. What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is called upon to help a terminally ill friend commit suicide. The voice is not solely or even primarily the narrator’s but Other: art consumed and people encountered become part of her own story; curiosity about other lives fuels empathy. A quiet novel that sneaks up to seize you by the heartstrings.

What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is called upon to help a terminally ill friend commit suicide. The voice is not solely or even primarily the narrator’s but Other: art consumed and people encountered become part of her own story; curiosity about other lives fuels empathy. A quiet novel that sneaks up to seize you by the heartstrings. Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, written in an aphoristic style. Set either side of Trump’s election in 2016, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are dead right. This felt like a perfect book for 2020 and its worries.

Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, written in an aphoristic style. Set either side of Trump’s election in 2016, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are dead right. This felt like a perfect book for 2020 and its worries. Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward: An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. I was particularly taken by the chapter narrated by the ant. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward: An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. I was particularly taken by the chapter narrated by the ant. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one. *The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Against a backdrop of flooding and bush fires, a series of personal catastrophes play out. A timely, quietly forceful story of how women cope with concrete and existential threats.

*The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Against a backdrop of flooding and bush fires, a series of personal catastrophes play out. A timely, quietly forceful story of how women cope with concrete and existential threats. To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss: These 10 stories from the last 18 years are melancholy and complex, often featuring several layers of Jewish family history. Europe, Israel, and film are frequent points of reference. “Future Emergencies,” though set just after 9/11, ended up feeling the most contemporary because it involves gas masks and other disaster preparations.

To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss: These 10 stories from the last 18 years are melancholy and complex, often featuring several layers of Jewish family history. Europe, Israel, and film are frequent points of reference. “Future Emergencies,” though set just after 9/11, ended up feeling the most contemporary because it involves gas masks and other disaster preparations. *Help Yourself by Curtis Sittenfeld: A bonus second UK release from Sittenfeld in 2020 after Rodham. Just three stories, but not leftovers; a strong follow-up to You Think It, I’ll Say It. They share the theme of figuring out who you really are versus what others think of you. “White Women LOL,” especially, compares favorably to Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age.

*Help Yourself by Curtis Sittenfeld: A bonus second UK release from Sittenfeld in 2020 after Rodham. Just three stories, but not leftovers; a strong follow-up to You Think It, I’ll Say It. They share the theme of figuring out who you really are versus what others think of you. “White Women LOL,” especially, compares favorably to Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age. You Will Never Be Forgotten by Mary South: In this debut collection, characters turn to technology to stake a claim on originality, compensate for losses, and leave a legacy. These 10 quirky, humorous stories never strayed so far into science fiction as to alienate me. I loved the medical themes and subtle, incisive observations about a technology-obsessed culture.

You Will Never Be Forgotten by Mary South: In this debut collection, characters turn to technology to stake a claim on originality, compensate for losses, and leave a legacy. These 10 quirky, humorous stories never strayed so far into science fiction as to alienate me. I loved the medical themes and subtle, incisive observations about a technology-obsessed culture. *Survival Is a Style by Christian Wiman: Wiman examines Christian faith in the shadow of cancer. This is the third of his books that I’ve read, and I’m consistently impressed by how he makes room for doubt, bitterness, and irony – yet a flame of faith remains. There is really interesting phrasing and vocabulary in this volume.

*Survival Is a Style by Christian Wiman: Wiman examines Christian faith in the shadow of cancer. This is the third of his books that I’ve read, and I’m consistently impressed by how he makes room for doubt, bitterness, and irony – yet a flame of faith remains. There is really interesting phrasing and vocabulary in this volume. Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho: Cho experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She alternates between her time in the mental hospital and her life before the breakdown, weaving in family history and Korean sayings and legends. It’s a painstakingly vivid account.

Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho: Cho experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She alternates between her time in the mental hospital and her life before the breakdown, weaving in family history and Korean sayings and legends. It’s a painstakingly vivid account. *The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: DNA tests can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction.

*The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: DNA tests can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction. *Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes: Fabes is an emergency room doctor in London and spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents. This warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of his travels achieves a perfect balance between world events, everyday discomforts, and humanitarian volunteering.

*Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes: Fabes is an emergency room doctor in London and spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents. This warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of his travels achieves a perfect balance between world events, everyday discomforts, and humanitarian volunteering. Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: Nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, but Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming in lots of information yet never losing sight of the big picture.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: Nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, but Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming in lots of information yet never losing sight of the big picture. *Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb: Jewish grandmothers are renowned for their fiercely protective love, but also for nagging. Both sides of the stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny, heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother. A real delight.

*Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb: Jewish grandmothers are renowned for their fiercely protective love, but also for nagging. Both sides of the stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny, heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother. A real delight. Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is a leader in the UK’s youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year and the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism.

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is a leader in the UK’s youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year and the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism. Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey: Trethewey grew up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, then moved with her mother to Atlanta. Her stepfather was abusive; her mother’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to their Memorial Drive apartment after 30 years had passed. A striking memoir, delicate and painful.

Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey: Trethewey grew up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, then moved with her mother to Atlanta. Her stepfather was abusive; her mother’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to their Memorial Drive apartment after 30 years had passed. A striking memoir, delicate and painful.

Apart from Dracula, my only previous experience of vampire novels was Deborah Harkness’s books. My first book from Paul Magrs ended up being a great choice because it’s pretty lighthearted and as much about the love of books as it is about supernatural fantasy – think of a cross between Jasper Fforde and Neil Gaiman. The title is a tongue-in-cheek nod to Helene Hanff’s memoir, 84 Charing Cross Road. Like Hanff, Aunt Liza sends letters and money to a London bookstore in exchange for books that suit her tastes. A publisher’s reader in New York City, Liza has to read new stuff for work but not-so-secretly prefers old books, especially about the paranormal – a love she shares with her gay bookseller friend, Jack.

Apart from Dracula, my only previous experience of vampire novels was Deborah Harkness’s books. My first book from Paul Magrs ended up being a great choice because it’s pretty lighthearted and as much about the love of books as it is about supernatural fantasy – think of a cross between Jasper Fforde and Neil Gaiman. The title is a tongue-in-cheek nod to Helene Hanff’s memoir, 84 Charing Cross Road. Like Hanff, Aunt Liza sends letters and money to a London bookstore in exchange for books that suit her tastes. A publisher’s reader in New York City, Liza has to read new stuff for work but not-so-secretly prefers old books, especially about the paranormal – a love she shares with her gay bookseller friend, Jack.

I read the first of this volume’s three suspense novellas and will save the others for future years of R.I.P. or Novellas in November. At 95 pages, it feels like a complete, stand-alone plot with solid character development and a believable arc. Paul and Elizabeth are academics marooned at different colleges: Paul is finishing up his postdoc and teaches menial classes at an English department in Iowa, where they live; Elizabeth commutes long-distance to spend four days a week in Chicago, where she’s on track for early tenure at the university.

I read the first of this volume’s three suspense novellas and will save the others for future years of R.I.P. or Novellas in November. At 95 pages, it feels like a complete, stand-alone plot with solid character development and a believable arc. Paul and Elizabeth are academics marooned at different colleges: Paul is finishing up his postdoc and teaches menial classes at an English department in Iowa, where they live; Elizabeth commutes long-distance to spend four days a week in Chicago, where she’s on track for early tenure at the university. Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. September can pressure her into anything, no matter how risky or painful, in games of “September Says.” But one time things went too far. That was the day they went out to the tennis courts to confront the girls at their Oxford school who had bullied July.

Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. September can pressure her into anything, no matter how risky or painful, in games of “September Says.” But one time things went too far. That was the day they went out to the tennis courts to confront the girls at their Oxford school who had bullied July.

Oates was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting, Eleven A.M. (The striking cover image is from a photographic recreation by Richard Tuschman. Very faithful except for the fact that Hopper’s armchair was blue.) A secretary pushing 40 waits in the New York City morning light for her married lover to arrive. She’s tired of him using her and keeps a sharp pair of sewing shears under her seat cushion. We bounce between the two characters’ perspectives as their encounter nears. He’s tempted to strangle her. Will today be that day, or will she have the courage to plunge those shears into his neck before he gets a chance? In this room, it’s always 11 a.m. The tension is well maintained, but the punctuation kind of drove me crazy. I might try the rest of the book next year.

Oates was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1926 painting, Eleven A.M. (The striking cover image is from a photographic recreation by Richard Tuschman. Very faithful except for the fact that Hopper’s armchair was blue.) A secretary pushing 40 waits in the New York City morning light for her married lover to arrive. She’s tired of him using her and keeps a sharp pair of sewing shears under her seat cushion. We bounce between the two characters’ perspectives as their encounter nears. He’s tempted to strangle her. Will today be that day, or will she have the courage to plunge those shears into his neck before he gets a chance? In this room, it’s always 11 a.m. The tension is well maintained, but the punctuation kind of drove me crazy. I might try the rest of the book next year.

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.”

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.” Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially

Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially  The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.”

The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.” Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.”

Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.” World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover?

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover? Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.”

Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.” The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from

The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from  Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating.

Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake [Sept. 3, Bodley Head / May 12, Random House] “Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into this hidden kingdom of life, and shows that fungi are key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways we think, feel and behave.” I like spotting fungi. Yes, yes, the title and cover are amazing, but also the author’s name!! – how could you not want to read this?

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake [Sept. 3, Bodley Head / May 12, Random House] “Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into this hidden kingdom of life, and shows that fungi are key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways we think, feel and behave.” I like spotting fungi. Yes, yes, the title and cover are amazing, but also the author’s name!! – how could you not want to read this? Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take.

Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take. The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary by Melissa Harrison [Nov. 5, Faber & Faber] “Moving from scrappy city verges to ancient, rural Suffolk, where Harrison eventually relocates, this diary—compiled from her beloved “Nature Notebook” column in The Times—maps her joyful engagement with the natural world and demonstrates how we must first learn to see, and then act to preserve, the beauty we have on our doorsteps.” I love seeing her nature finds on Twitter. I think her writing will suit this format.

The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary by Melissa Harrison [Nov. 5, Faber & Faber] “Moving from scrappy city verges to ancient, rural Suffolk, where Harrison eventually relocates, this diary—compiled from her beloved “Nature Notebook” column in The Times—maps her joyful engagement with the natural world and demonstrates how we must first learn to see, and then act to preserve, the beauty we have on our doorsteps.” I love seeing her nature finds on Twitter. I think her writing will suit this format.

Genova’s writing, Jodi Picoult-like, keeps you turning the pages; I read 225+ pages in an afternoon. There’s true plotting skill to how Genova uses a close third-person perspective to track the mental decline of Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language,” yet her grasp of language becomes ever more slippery even as her thought life remains largely intact. I also particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Cambridge and its weather, and family meals and rituals. There’s a certain amount of suspension of disbelief required – Would the disease really progress this quickly? Would Alice really be able to miss certain abilities and experiences once they were gone? – and ultimately I preferred the 2014 movie version, but this would be a great book to thrust at any caregiver or family member who’s had to cope with dementia in someone close to them.

Genova’s writing, Jodi Picoult-like, keeps you turning the pages; I read 225+ pages in an afternoon. There’s true plotting skill to how Genova uses a close third-person perspective to track the mental decline of Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language,” yet her grasp of language becomes ever more slippery even as her thought life remains largely intact. I also particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Cambridge and its weather, and family meals and rituals. There’s a certain amount of suspension of disbelief required – Would the disease really progress this quickly? Would Alice really be able to miss certain abilities and experiences once they were gone? – and ultimately I preferred the 2014 movie version, but this would be a great book to thrust at any caregiver or family member who’s had to cope with dementia in someone close to them. Other fictional takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Other fictional takes on dementia that I can recommend:  A remarkable insider’s look at the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Mitchell took several falls while running near her Yorkshire home, but it wasn’t until she had a minor stroke in 2012 that she and her doctors started taking her health problems seriously. In July 2014 she got the dementia diagnosis that finally explained her recurring brain fog. She was 58 years old, a single mother with two grown daughters and a 20-year career in NHS administration. Having prided herself on her good memory and her efficiency at everything from work scheduling to DIY, she was distressed that she couldn’t cope with a new computer system and was unlikely to recognize the faces or voices of colleagues she’d worked with for years. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she took early retirement – a decision that she feels was forced on her by a system that wasn’t willing to make accommodations for her.

A remarkable insider’s look at the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Mitchell took several falls while running near her Yorkshire home, but it wasn’t until she had a minor stroke in 2012 that she and her doctors started taking her health problems seriously. In July 2014 she got the dementia diagnosis that finally explained her recurring brain fog. She was 58 years old, a single mother with two grown daughters and a 20-year career in NHS administration. Having prided herself on her good memory and her efficiency at everything from work scheduling to DIY, she was distressed that she couldn’t cope with a new computer system and was unlikely to recognize the faces or voices of colleagues she’d worked with for years. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she took early retirement – a decision that she feels was forced on her by a system that wasn’t willing to make accommodations for her.

Other nonfiction takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Other nonfiction takes on dementia that I can recommend:

Dear Fahrenheit 451

Dear Fahrenheit 451

#1: I fully expect Richard Powers to win for The Overstory. This is the one I’m partway through; I started reading a library copy on Friday. I’m so impressed by the novel’s expansive nature. It seems to have everything: love, war, history, nature, politics, technology, small-town life, family drama, illness, accidents, death. And all of human life is overshadowed and put into perspective by the ancientness of trees, whose power we disregard at a cost. I’m reminded of the work of Jonathan Franzen (Freedom + Purity), as well as Barbara Kingsolver’s latest, Unsheltered – though Powers is prophetic where she’s polemic.

#1: I fully expect Richard Powers to win for The Overstory. This is the one I’m partway through; I started reading a library copy on Friday. I’m so impressed by the novel’s expansive nature. It seems to have everything: love, war, history, nature, politics, technology, small-town life, family drama, illness, accidents, death. And all of human life is overshadowed and put into perspective by the ancientness of trees, whose power we disregard at a cost. I’m reminded of the work of Jonathan Franzen (Freedom + Purity), as well as Barbara Kingsolver’s latest, Unsheltered – though Powers is prophetic where she’s polemic. #2: Washington Black by Esi Edugyan is a good old-fashioned adventure story about a slave who gets the chance to leave his Barbados sugar plantation behind when he becomes an assistant to an abolitionist inventor, Christopher “Titch” Wilde. Wash discovers a talent for drawing and a love for marine life and pursues these joint interests in the disparate places where life takes him. Part One was much my favorite; none of what followed quite matched it in depth or pace. Still, I enjoyed following along on Wash’s escapades, and I wouldn’t mind seeing this take the prize – it would be great to see a woman of color win.

#2: Washington Black by Esi Edugyan is a good old-fashioned adventure story about a slave who gets the chance to leave his Barbados sugar plantation behind when he becomes an assistant to an abolitionist inventor, Christopher “Titch” Wilde. Wash discovers a talent for drawing and a love for marine life and pursues these joint interests in the disparate places where life takes him. Part One was much my favorite; none of what followed quite matched it in depth or pace. Still, I enjoyed following along on Wash’s escapades, and I wouldn’t mind seeing this take the prize – it would be great to see a woman of color win.  #3: The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner: Kushner is well respected, though I’ve failed to get on with her fiction before. An inside look at the prison system, this could be sufficiently weighty and well-timed to win.

#3: The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner: Kushner is well respected, though I’ve failed to get on with her fiction before. An inside look at the prison system, this could be sufficiently weighty and well-timed to win. #4: Everything Under by Daisy Johnson: A myth-infused debut novel about a mother and daughter. On my library stack to read next, and the remaining title from the shortlist I’m most keen to read.

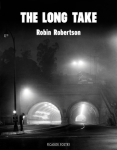

#4: Everything Under by Daisy Johnson: A myth-infused debut novel about a mother and daughter. On my library stack to read next, and the remaining title from the shortlist I’m most keen to read. #5: The Long Take by Robin Robertson: A novel, largely in verse, about the aftermath of war service. Also on my library stack. Somewhat experimental forms like this grab Booker attention, but this might be too under-the-radar to win.

#5: The Long Take by Robin Robertson: A novel, largely in verse, about the aftermath of war service. Also on my library stack. Somewhat experimental forms like this grab Booker attention, but this might be too under-the-radar to win. #6: Milkman by Anna Burns: Set in Belfast during the Troubles or a dystopian future? From my Goodreads friends’ reviews this sounds wooden and overwritten. Like the Kushner, I’d consider reading it if it wins but probably not otherwise.

#6: Milkman by Anna Burns: Set in Belfast during the Troubles or a dystopian future? From my Goodreads friends’ reviews this sounds wooden and overwritten. Like the Kushner, I’d consider reading it if it wins but probably not otherwise.