Healing in (Re)Verse: Poems about not dying. Yet by BS Casey (Blog Tour)

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

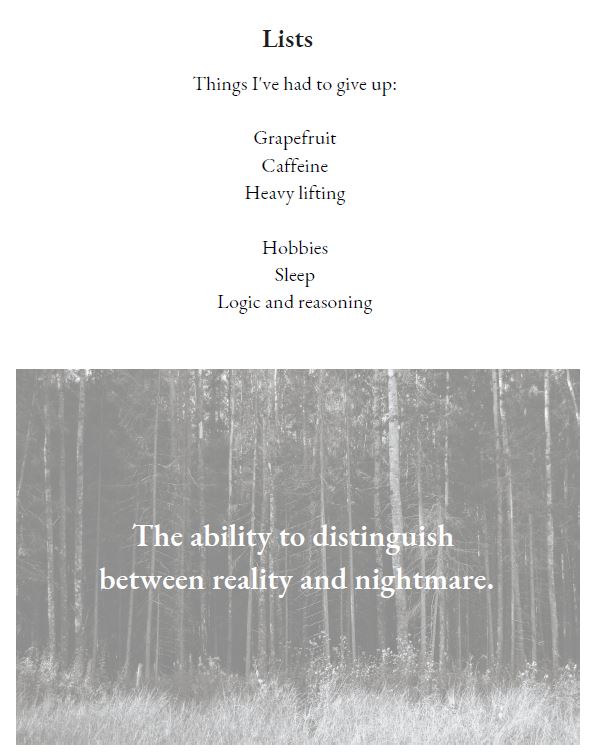

End rhymes, slant rhymes, and alliteration form part of the sonic palette. Through imagined conversations with the self and with others who have hurt the speaker or put them down, they wrestle with concepts of forgiveness and self-love. “Just a girl” chronicles instances of sexualized verbal and emotional abuse. The use of repeated words and phrases, with minor adaptations, along with the themes of trauma and recovery, reminded me of Rupi Kaur’s performance poetry-inspired style. “Monster” is more like a short story with its prose paragraphs and imagined dialogue. “How are you” is an erasure poem that crosses out all the possible genuine answers to that question in between, leaving only the socially acceptable “I’m fine thanks. … how are you?”

The pages’ stark black-and-white design is softened by background images of flowers, feathers, forests, candle flames, and shadows falling through windows. Although the tone is overwhelmingly sad, there is also some wry humour, as in the below.

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Poetry – writing it or reading it – can be a great way for people to work through the pain of mental ill health and chronic illness and not feel so alone. That’s one reason I’m looking forward to the return of the Barbellion Prize later this year. “The Barbellion Prize celebrates and promotes writing that represents the experience of chronic illness and disability. The prize is named after the diarist W.N.P. Barbellion, who wrote eloquently on his life with multiple sclerosis (MS). It is a cross-genre award for literature published in the English language.” I’ve donated to get it up and running again; maybe you can, too?

My thanks to Random Things Tours and the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

April 3rd Releases by Emily Jungmin Yoon & Jean Hannah Edelstein

It’s not often that I manage to review books for their publication date rather than at the end of the month, but these two were so short and readable that I polished them off over the first few days of April. So, out today in the UK: a poetry collection about Asian American identity and environmental threat, and a memoir in miniature about how body parts once sexualized and then functionalized are missed once they’re gone.

Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon (2024)

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

Published in the USA by Knopf on October 22, 2024. With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein

From my Most Anticipated list. I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir This Really Isn’t About You, and I regularly read her Substack. This micro-memoir in three essays explores the different roles breasts have played in her life: “Sex” runs from the day she went shopping for her first bra as a teenager with her mother through to her early thirties living in London. Edelstein developed early and eventually wore size DD, which attracted much unwanted attention in social situations and workplaces alike. (And not just a slightly sleazy bar she worked in, but an office, too. Twice she was groped by colleagues; the second time she reported it. But: drunk, Christmas party, no witnesses; no consequences.) “It felt like a punishment, a consequence of my own behavior (being a woman, having a fun night out, doing these things while having large breasts),” she writes.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

Although this is a likable book, the retelling is quite flat; better that than mawkish, certainly, but none of the experiences feel particularly unique. It’s more a generic rundown of what it’s like to be female – which, yes, varies to an extent but not that much if we’re talking about the male gaze. There wasn’t the same spark or wit that I found in Edelstein’s first book. Perhaps in the context of a longer memoir, I would have appreciated these essays more.

With thanks to Phoenix for the free copy for review.