Review: The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley (2023)

The Nero Book Awards category winners will be announced on Tuesday. I haven’t had a chance to read as many of the nominees as I would like, but I’m catching up on one that I’ve wanted to read ever since I first heard about it early last year. Even though Stephen Collins sums up about my feelings about coldwater swimming well in this cartoon –

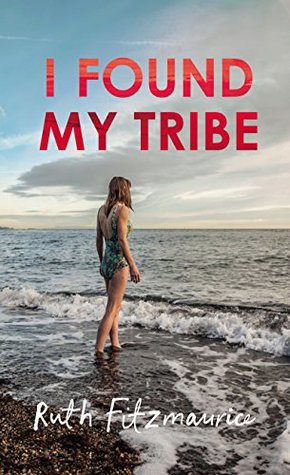

– I was drawn to The Tidal Year for several reasons. First off, I’ll read just about any bereavement memoir going. Second, I love following along on a year challenge. Third, even though I haven’t been much of a swimmer since childhood, I appreciate how outdoor swimming combines observation of nature and the seasons with achievable bodily exploits; you don’t have to be an exercise nut or undergo lots of training to get into it. There was a spate of swimming memoirs back in 2017, including Jessica J. Lee’s superb Turning and Ruth Fitzmaurice’s I Found My Tribe. Headlines often tout the physical benefits of coldwater swimming, but it’s the emotional benefits that Bromley emphasizes in this record of facing grief and opening up to love.

Bromley was the middle of five children but her boisterous family’s dynamic went out of kilter when her younger brother Tom was diagnosed with bone cancer and died at age 19. Suddenly she could hardly talk to her mother, let alone to Tom’s twin, Emma. Isolated in London, where she worked in music journalism, she roped her friend Miri into wild swimming excursions and threw herself into Internet dating. She and Miri concocted a plan to swim in all of Britain’s mainland tidal pools (saltwater enclosed by manmade elements) in a year; she started seeing Jem, a free-spirited documentary filmmaker – but also Flip, a Black actor she met when he came to buy her neighbour’s antique chairs; he nicknamed her “Poet” and encouraged her in her writing.

Each short chapter is identified by a place name and its geographical coordinates. Most often, these correspond to a swimming destination, but they can also be clues to interludes or flashbacks, whether set in London (“Jem’s Skylight”), on the last night she spent by Tom’s hospital bedside, or at the Brecon Beacons home her parents moved to after Tom’s death. A lot of the tidal pools are in Devon and Cornwall, but she and Miri also make expeditions to Scotland and Wales and elsewhere along the south coast.

At a certain point Bromley realizes that they aren’t going to hit every single pool before the year is over, but the goal starts to matter less than the slow internal transformation that’s taking place. “Swimming had been a way for me to rediscover my body as a place of power, play and movement.” We see the gradual shifts: she’s more able to talk about Tom, she commits to her writing through a Cambridge course, she’s a supportive big sister to Emma, and she breaks it off with one of the boyfriends.

I had to suppress my judgemental side here. I know monogamy is not a universal value, especially among a younger generation, and Bromley does acknowledge that she was behaving badly in stringing two partners along – grief leads people to make decisions they might not normally. The other niggle for this pedantic proofreader was the non-standard way of introducing dialogue. Bromley chose to put all dialogue in italics – fine with me – but doesn’t consistently bracket phrases with “I said” or “she asked.” Usually it’s clear enough, but sometimes the interruption of speech with gesture is downright maddening, e.g., “There’s this, I blew on the tea, well inside me” and “It’s magic isn’t it, Miri rolled down her window”.

But I was (mostly) able to excuse this stylistic quirk because Bromley writes so acutely about herself and others, giving a lucid sense of the passage of time and the particularities of place. She’s observant and funny, too. “I find what people often mean when they say ‘resilient’ is that they want people to be good at suffering in silence.” Youthful, playful, sexy: those are unusual characteristics for a book on the fringes of nature writing. The voice was distinctive enough that, though I’ve rarely met a 400+-page book that couldn’t stand to be closer to 300, I thoroughly enjoyed my time spent with it.

The Nero Awards judges chose an all-female inaugural shortlist made up of four works of opinionated nonfiction. I’ve read the first 42 pages of Undercurrent, Natasha Carthew’s memoir of growing up in poverty in Cornwall, and will probably leave it there; I didn’t care for the writing in Fern Brady’s Strong Female Character, her memoir of being a young autistic woman (it’s said to be funny but I didn’t get the humour). Hags, Victoria Smith’s book about the societal marginalizing of older women, is the sort of book I’d skim from the library but am unlikely to read in its entirety. I would have been very happy for Bromley to win.

With thanks to Coronet (Hodder & Stoughton) for the free copy for review.

I Found My Tribe by Ruth Fitzmaurice

Ruth Fitzmaurice’s husband, a filmmaker named Simon, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease in 2008. Like Stephen Hawking, he is wheelchair-bound and motionless, communicating only through the mechanical voice of an eye gaze computer.

My husband is a wonder to me but he is hard to find. I search for him in our home. He breathes through a pipe in his throat. He feels everything but cannot move a muscle. I lie on his chest counting mechanical breaths. I hold his hand but he doesn’t hold back. His darting eyes are the only windows left. I won’t stop searching.

Between their five children under the age of 10 (including twins conceived after Simon’s diagnosis), an aggressive basset hound, and Simon’s army of nurses coming and going 24 hours a day, this is one chaotic household. The recurring challenge is to find pockets of stillness – daydreaming, staring at trees outside her window – and to learn what things can bring her back from the brink of despair, again and again.

Often these are outdoor experiences: a last hurrah of a six-month holiday in Australia, running, and especially plunging into the Irish Sea with her “Tragic Wives’ Swimming Club” – a group that includes her friend Michelle, whose husband is also in a wheelchair after a motorbike crash, and her favorite of Simon’s nurses, Marian, who has a serious car accident.

Often these are outdoor experiences: a last hurrah of a six-month holiday in Australia, running, and especially plunging into the Irish Sea with her “Tragic Wives’ Swimming Club” – a group that includes her friend Michelle, whose husband is also in a wheelchair after a motorbike crash, and her favorite of Simon’s nurses, Marian, who has a serious car accident.

Rather than a straight chronological narrative, this is a set of brief thematic essays with titles like “Dancing,” “Fear,” “Twins” and “Holidays.” Fitzmaurice’s story is one you piece together through vivid vignettes from her home life. Her prose is generally composed of short, simple phrases; as with Cathy Rentzenbrink’s The Last Act of Love, you can tell there is deep emotion pulsing under the measured sentences. With such huge questions in play – How much can one person take? What would losing one’s mind look like? – there’s no need for added drama, after all. Instead, the author turns to whimsy, toying with the superhero cliché for caregivers and wondering what magic might be at work in her situation.

I was particularly impressed by how Fitzmaurice holds the past and present in her mind, and by how she uses an outsider’s perspective to imagine herself out of her circumstances. At times she uses the third person for these visions of herself as a younger woman newly in love:

The young wife at her kitchen table knows about deep magic. But I know her future. Life is going to push and pull her like a wave. She doesn’t have a choice and neither do I. Come with me, dear girl, sit at my tablecloth. The journey is upon us and to survive it, you can’t just ride the wave, you have to become one. Can we do this? Let’s go. Becoming a wave just might be the deepest magic of them all.

There are so many poignant moments in this book: memories of their determinedly vegetarian wedding; pulling out all the stops for Simon’s fortieth birthday with customized art installations to brighten his view; leaving the marital bed – now a “hospital contraption” – after six years of MND being a part of their lives; a full moon swim with the Tragic Wives on her and Simon’s anniversary. But all the quiet, everyday stuff has power too, especially her interactions with her precocious children, who are confused about why Dadda is like this.

If I had one tiny complaint, it’s that Simon feels like something of a shadowy figure. In flashbacks we get a real sense of his forceful personality, but this new, silent Simon in the wheelchair is a mystery. Only once or twice does she record words he ‘says’ to her via his computer. Perhaps this is inevitable given how locked into himself he’s become. However, he was still capable of becoming the first person with MND to direct a feature film, on location in County Wicklow (My Name Is Emily). He has told his own story elsewhere; in his wife’s telling, their ventures now seem so separate that they rarely appear as equal partners.

It’s my tenth wedding anniversary tomorrow; as I was reading this I kept thinking that, for as much as I complain (to myself) about how hard marriage is, I’ve had it so easy. The stresses a couple face when caregiving of one partner is involved are immense. Fitzmaurice has found herself part of a tribe she probably never wanted to join: the walking wounded, with pain behind their eyes and worry never far from their minds. But in the midst of it she’s also found the band of family and friends who help her pull through each time. Her lovely book – wry, wise, and realistic – will strike a chord with anyone who has faced illness and family tragedy.

My rating:

I Found My Tribe is published in the UK today, July 6th, by Chatto & Windus. My thanks to the publisher for the review copy.

Note: Fitzmaurice got her book deal on the strength of a series of pieces she wrote for the Irish Times. You can read an extract from the book here. Film rights to her story have been sold to Element Pictures; more details are here. A documentary about Simon’s life, It’s Not Yet Dark, based on his memoir of the same title, has recently been released. For more information see here (this article also showcases multiple family photos).

Update: Simon Fitzmaurice died on October 26, 2017, aged 43.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: O’Farrell captures fragments of her life through essays on life-threatening illnesses and other narrow escapes she’s experienced. The pieces aren’t in chronological order and aren’t intended to be comprehensive. Instead, they crystallize the fear and pain of particular moments in time, and are rendered with the detail you’d expect from her novels. She’s been mugged at machete point, nearly drowned several times, had a risky first labor, and was almost the victim of a serial killer. (My life feels awfully uneventful by comparison!) But the best section of the book is its final quarter: an essay about her childhood encephalitis and its lasting effects, followed by another about her daughter’s extreme allergies.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: O’Farrell captures fragments of her life through essays on life-threatening illnesses and other narrow escapes she’s experienced. The pieces aren’t in chronological order and aren’t intended to be comprehensive. Instead, they crystallize the fear and pain of particular moments in time, and are rendered with the detail you’d expect from her novels. She’s been mugged at machete point, nearly drowned several times, had a risky first labor, and was almost the victim of a serial killer. (My life feels awfully uneventful by comparison!) But the best section of the book is its final quarter: an essay about her childhood encephalitis and its lasting effects, followed by another about her daughter’s extreme allergies.  History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund: Fridlund’s Minnesota-set debut novel is haunted by a dead child. From the second page readers know four-year-old Paul is dead; a trial is also mentioned early on, but not until halfway does Madeline Furston divulge how her charge died. This becomes a familiar narrative pattern: careful withholding followed by tossed-off revelations that muddy the question of complicity. The novel’s simplicity is deceptive; it’s not merely a slow-building coming-of-age story with Paul’s untimely death at its climax. For after a first part entitled “Science”, there’s still half the book to go – a second section of equal length, somewhat ironically labeled “Health”. (Reviewed for the TLS.)

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund: Fridlund’s Minnesota-set debut novel is haunted by a dead child. From the second page readers know four-year-old Paul is dead; a trial is also mentioned early on, but not until halfway does Madeline Furston divulge how her charge died. This becomes a familiar narrative pattern: careful withholding followed by tossed-off revelations that muddy the question of complicity. The novel’s simplicity is deceptive; it’s not merely a slow-building coming-of-age story with Paul’s untimely death at its climax. For after a first part entitled “Science”, there’s still half the book to go – a second section of equal length, somewhat ironically labeled “Health”. (Reviewed for the TLS.)  Modern Death: How Medicine Changed the End of Life by Haider Warraich: A learned but engaging book that intersperses science, history, medicine and personal stories. The first half is about death as a medical reality, while the second focuses on social aspects of death: religious beliefs, the burden on families and other caregivers, the debate over euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, and the pros and cons of using social media to share one’s journey towards death. (See

Modern Death: How Medicine Changed the End of Life by Haider Warraich: A learned but engaging book that intersperses science, history, medicine and personal stories. The first half is about death as a medical reality, while the second focuses on social aspects of death: religious beliefs, the burden on families and other caregivers, the debate over euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, and the pros and cons of using social media to share one’s journey towards death. (See

This Is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor by Adam Kay

This Is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor by Adam Kay

No Apparent Distress: A Doctor’s Coming-of-Age on the Front Lines of American Medicine by Rachel Pearson: Pearson describes her Texas upbringing and the many different hands-on stages involved in her training: a prison hospital, gynecology, general surgery, rural family medicine, neurology, dermatology. Each comes with memorable stories, but it’s her experience at St. Vincent’s Student-Run Free Clinic on Galveston Island that stands out most. Pearson speaks out boldly about the divide between rich and poor Americans (often mirrored by the racial gap) in terms of what medical care they can get. A clear-eyed insider’s glimpse into American health care.

No Apparent Distress: A Doctor’s Coming-of-Age on the Front Lines of American Medicine by Rachel Pearson: Pearson describes her Texas upbringing and the many different hands-on stages involved in her training: a prison hospital, gynecology, general surgery, rural family medicine, neurology, dermatology. Each comes with memorable stories, but it’s her experience at St. Vincent’s Student-Run Free Clinic on Galveston Island that stands out most. Pearson speaks out boldly about the divide between rich and poor Americans (often mirrored by the racial gap) in terms of what medical care they can get. A clear-eyed insider’s glimpse into American health care.  The Tincture of Time: A Memoir of (Medical) Uncertainty by Elizabeth L. Silver:

The Tincture of Time: A Memoir of (Medical) Uncertainty by Elizabeth L. Silver: