20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

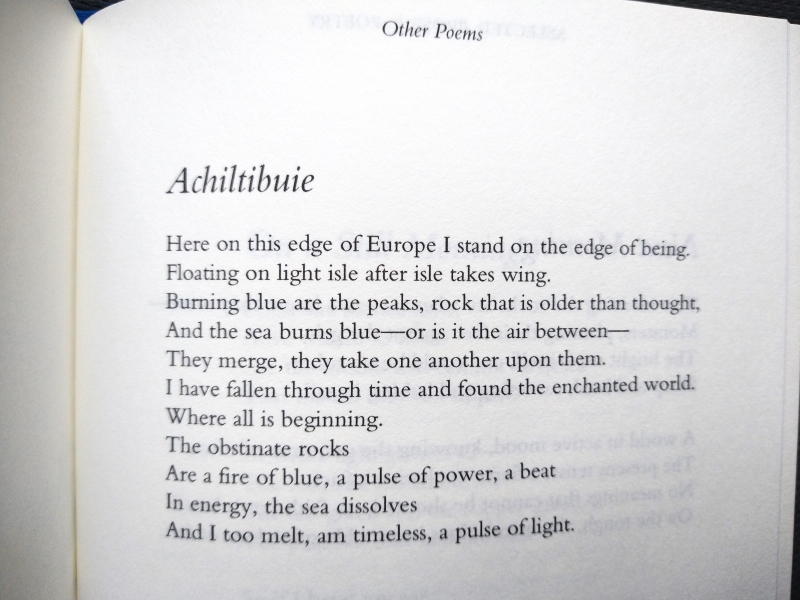

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

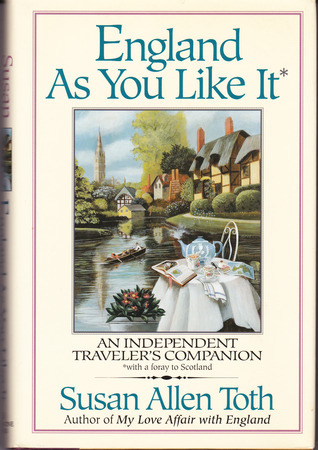

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Spring Reads, Part I: Violets and Rain

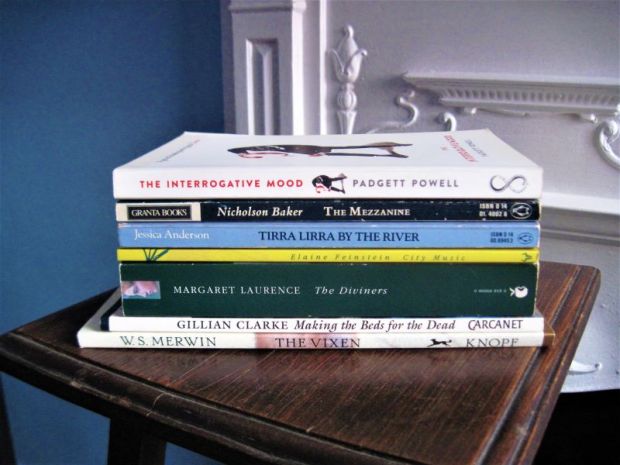

We had both rain and spring sunshine on a recent overnight trip to Bridport, Dorset – a return visit after enjoying it so much in 2019. Several elements were repeated: Dorset Nectar cider farm, dinner at Dorshi, and a bookshop and charity shop crawl of the main streets. While we didn’t revisit Thomas Hardy sites, I spent plenty of time at Max Gate by reading Elizabeth Lowry’s The Chosen. Beach walks plus one in the New Forest on the way back were splendid. This was my haul from Bridport Old Books. Stocking up on novellas and poetry, plus a novel by a Canadian author I’ve enjoyed work from before.

Now for a quick look at two tangentially spring-related books I’ve read recently: a short novel about two women’s wartime experiences of motherhood and an elegiac and allusive poetry collection.

Violets by Alex Hyde (2022)

I was intrigued by the sound of this debut novel, which juxtaposes the lives of two young British women named Violet at the close of the Second World War. One miscarries twins and, told she’ll not be able to bear children, has to rethink her whole future; another sails from Wales to Italy on ATS war service, hiding the fact that she’s pregnant by a departed foreign soldier. Hyde’s spare style – no speech marks; short paragraphs or solitary lines separated by spaces – alternates between their stories in brief numbered chapters, bringing them together in a perhaps predictable way that also forms a reimagining of her father’s life story. The narration at times addresses this future character in poems that I think are supposed to be fond and prophetic but I instead found strangely blunt and even taunting (as in the excerpt below). There’s inadequate time to get to know, or care about, either Violet.

Can you feel it, Pram Boy?

Can you march in time?

A change, a hardening,

the jarring of the solid ground as she treads,

gets her pockets picked.

[…]

Quick! March!

And your Mama, Pram Boy,

yeasty in her private parts.

Granta sent a free copy. Violets came out in paperback in February.

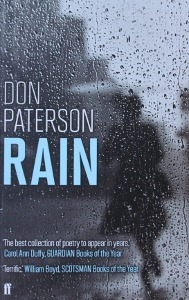

Rain by Don Paterson (Faber, 2009)

I’d previously read Paterson’s 40 Sonnets, in 2015. This collection is in memoriam of the late poet Michael Donaghy, the subject of the late multi-part “Phantom.” There are a couple of poems in Scots and a sequence of seven nature-infused ones designated as being “after” poets from Li Po to Robert Desnos. Several appear to express concern for a son. There’s a haiku-like rhythm to the short stanzas of “Renku: My Last Thirty-Five Deaths.” I didn’t understand why “Unfold i.m. Akira Yoshizawa” was a blank page until I looked him up and learned that he was a famous origamist. The title poem closes the collection:

I’d previously read Paterson’s 40 Sonnets, in 2015. This collection is in memoriam of the late poet Michael Donaghy, the subject of the late multi-part “Phantom.” There are a couple of poems in Scots and a sequence of seven nature-infused ones designated as being “after” poets from Li Po to Robert Desnos. Several appear to express concern for a son. There’s a haiku-like rhythm to the short stanzas of “Renku: My Last Thirty-Five Deaths.” I didn’t understand why “Unfold i.m. Akira Yoshizawa” was a blank page until I looked him up and learned that he was a famous origamist. The title poem closes the collection:

I love all films that start with rain:

rain, braiding a windowpane

or darkening a hung-out dress

or streaming down her upturned face;

one big thundering downpour

right through the empty script and score

before the act, before the blame,

before the lens pulls through the frame

to where the woman sits alone

beside a silent telephone

I liked individual passages or images but didn’t find much of a connecting theme behind Paterson’s disparate interests. (University library)

Another favourite passage:

So I collect the dull things of the day

in which I see some possibility

[…]

I look at them and look at them until

one thing makes a mirror in my eyes

then I paint it with the tear to make it bright.

This is why I sit up through the night.

(from “Why Do You Stay Up So Late?”)

And a DNF:

Corpse Beneath the Crocus by N.N. Nelson – I loved the title and the cover, and a widow’s bereavement memoir in poems seemed right up my street. I wish I’d realized Atmosphere is a vanity press, which would explain why these are among the worst poems I’ve read: cliché-riddled and full of obvious sentiments and metaphors as she explores specific moments but mostly overall emotions. Three excerpts:

Corpse Beneath the Crocus by N.N. Nelson – I loved the title and the cover, and a widow’s bereavement memoir in poems seemed right up my street. I wish I’d realized Atmosphere is a vanity press, which would explain why these are among the worst poems I’ve read: cliché-riddled and full of obvious sentiments and metaphors as she explores specific moments but mostly overall emotions. Three excerpts:

All things die

In the flowering cycle

Of growth and life

Time passes

Like sand in an hourglass

Feelings are changeful

Like the tide

Ebbing and flowing

“Love Letter,” a prose piece, held the most promise, which suggests Nelson would have been better off attempting memoir. I slogged (hate-read, really) my way through to the halfway point but could bear it no longer. (NetGalley)

I have a few more spring-themed books on the go: Hoping for a better set next time!

Any spring reads on your plate?

Review & Giveaway: Hame by Annalena McAfee

As I mentioned on Tuesday, I previously knew of Annalena McAfee only as Mrs. Ian McEwan, though she has a distinguished literary background: she founded the Guardian Review and edited it for six years, was Arts and Literary Editor of the Financial Times, and is the author of multiple children’s books and one previous novel for adults, The Spoiler (2011).

As I mentioned on Tuesday, I previously knew of Annalena McAfee only as Mrs. Ian McEwan, though she has a distinguished literary background: she founded the Guardian Review and edited it for six years, was Arts and Literary Editor of the Financial Times, and is the author of multiple children’s books and one previous novel for adults, The Spoiler (2011).

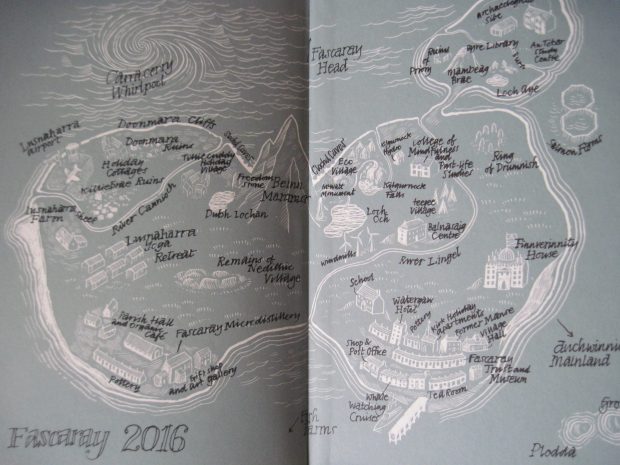

Well, anyone who reads Hame will be saying “Ian who?” as this is on such a grand scale compared to anything McEwan has ever attempted. The subtitle, “The Fascaray Archives,” gives an idea of how thorough McAfee means to be: the life of fictional poet Grigor McWatt is her way into everything that forms the Scottish identity. Her invented island of Fascaray is a carefully constructed microcosm of Scotland from ancient times to today. I loved the little glimpses of recent history, like the referendum on independence and a Donald Trump figure, billionaire “Archie Tupper,” bulldozing an environmentally sensitive area to build his new golf course (this really happened, in Aberdeenshire in 2012).

Narrator Mhairi McPhail arrives on Fascaray in August 2014, her nine-year-old daughter Agnes in tow. She’s here to oversee the opening of a new museum, edit a seven-volume edition of McWatt’s magnum opus, The Fascaray Compendium (a 70-year journal detailing the island’s history, language, flora, fauna and customs), and complete a critical biography of the poet. Over the next four months she often questions the feasibility of her multi-strand project. She also frets about her split from Marco, whom she left back in New York City after their separate infidelities. And her rootlessness – she’s Canadian via Scotland but has spent a lot of time in the States, giving her a mixed-up heritage and accent – is a constant niggle.

Mhairi’s narrative sections share space with excerpts from her biography of McWatt and extracts from McWatt’s own writing: The Fascaray Compendium, newspaper columns, letters to on-again, off-again lover Lilias Hogg, and Scots translations of famous poets from Blake to Yeats. We learn of key events from the island’s history through Mhairi’s biography and McWatt’s prose, including ongoing tension between lairds and crofters, Finnverinnity House being used as a Special Ops training school during World War II, a lifeboat lost in a gale in the 1970s, and the way the fishing industry is now ceding to hydroelectric power.

The balance between the alternating elements isn’t quite right – sections from Mhairi’s contemporary diary seem to get shorter as the novel goes along, such that it feels like there’s not enough narrative to anchor the book. Faced with yet more Scots poetry and vocabulary lists, or passages from Mhairi’s dry biography, it’s mighty tempting to skim.

That’s a shame, as the novel contains some truly lovely writing, particularly in McWatt’s nature observations:

In July and August, on rare days of startling and sustained heat, dragonflies as blue as the cloudless skies shimmer over cushions of moss by the burn while the midges, who abhor direct sunlight, are nowhere to be seen. Out to sea, somnolent groups of whales pass like cortèges of cruise ships and around them dolphins and porpoises joyously arc and dip as if stitching the ocean’s silken canopy of turquoise, gentian and cobalt.

For centuries male Fascaradians have sailed in the autumn, at the time of the ripe barley and the fruiting buckthorn, to hunt the plump young solan geese or gannets – the guga – near their nesting sites on the uninhabited rock pinnacles of Plodda and Grodda. No true Fascaradian can suffer vertigo since the scaling of these granite towers is done without the aid of mountaineers’ crampons or picks.

“Hame” means home in Scots – like in McWatt’s claim to fame, the folk-pop song “Hame tae Fascaray” – and themes of home and identity are strong here. The novel asks to what extent identity is bound up with a particular country and language, and whether we can craft our own selves. Must the place you come from always be the same as the home you choose? I could relate to Mhairi’s feeling that there’s nowhere she belongs, whether she’s in the bustle of New York or “marooned on a patch of damp peat floating in the North Sea.”

A map of the island from the inside of the back cover.

Although the blend of elements initially made me think that this would resemble A.S. Byatt’s Possession, it’s actually more like Rachel Cantor’s Good on Paper, which similarly stars a scholar who’s a single parent to a precocious daughter. In places I was also reminded of the work of Scarlett Thomas, Sara Maitland and Sarah Moss, and there’s even an echo of Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks in the inventories of dialect words.

If you’ve done much traveling in Scotland, an added pleasure of the novel is trying to spot places you’ve been. (I thought I could see traces of Stromness, Orkney; indeed, McWatt reminded me most of Orcadian poet George Mackay Brown.) The comprehensive, archival approach didn’t completely win me over, but I was impressed by the book’s scope and its affectionate portrait of a beloved country. McAfee is of Scots-Irish parentage herself, and you can tell this is a true labor of love, and a cogent tribute.

Hame was published by Harvill Secker on February 9th. With thanks to Anna Redman for sending a free copy for review.

My rating:

Giveaway Announcement!

I was accidentally sent two copies of Hame, so I am giving one away to a reader. Alas, this giveaway will have to be UK-only – the book is a hardback of nearly 600 pages, so would be prohibitively expensive to send abroad.

If you’re interested in winning a copy, simply leave a comment to that effect below. The competition will be open through the end of Friday the 17th and I will choose a winner at random on Saturday the 18th, to be announced via the comments and a personal e-mail.

Good luck!