Winter Reading, Part II: “Snow” Books by Coleman, Rice & Whittell

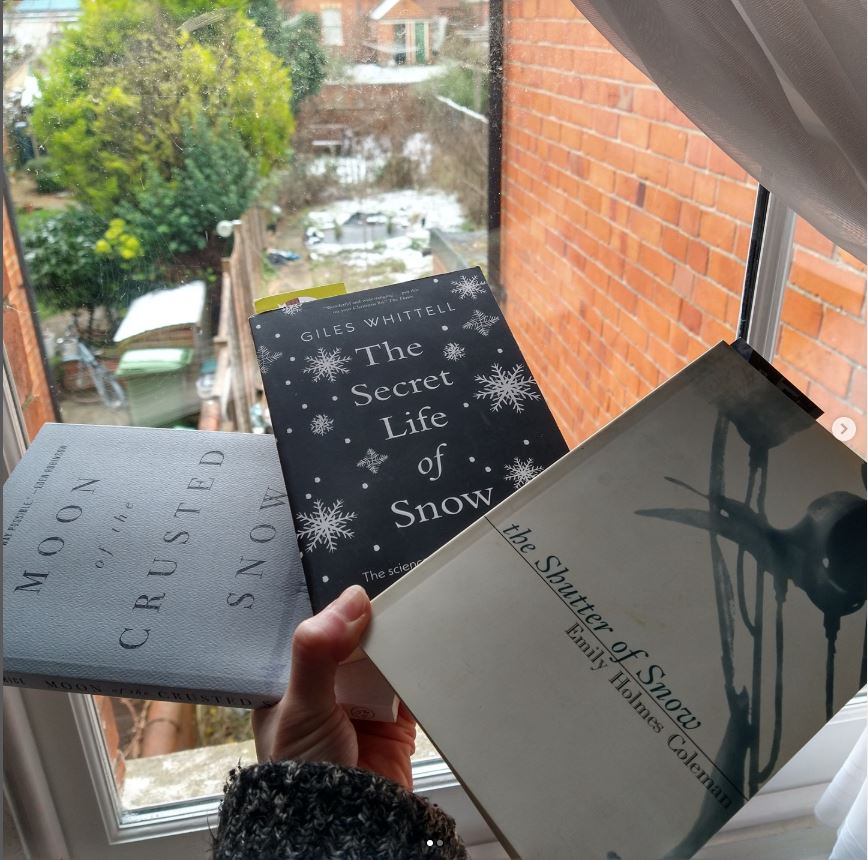

Here I am squeaking in on the day before the spring equinox – when it’s predicted to be warmer than Ibiza here in southern England, as headlines have it – with a few snowy reads that have been on my stack for much of the winter. I started reading this trio when we got a dusting back in January, in case (as proved to be true) it was our only snow of the year. I have an arresting work of autofiction that recreates a period of postpartum psychosis, a mildly dystopian novel by a First Nations Canadian, and a snow-lover’s compendium of science and trivia.

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

Snow had an unreality to it. Was this because of its pace or its beauty? There was an accompanying clarity to snow as well, especially snow, drifting snow. What was and wasn’t important were made distinct. Certain facts became chillingly apparent. Pain, for one.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman (1930)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (2018)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) ![]()

The Secret Life of Snow: The science and the stories behind nature’s greatest wonder by Giles Whittell (2018)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Whittell’s mention of the U.S. East Coast “Snowmaggedon” of February 2010 had me digging out photos my mother sent me of the aftermath at our family home of the time.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately? Or is it looking like spring?

Some 2024 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Shortest books read this year: The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke – a standalone short story (unfortunately, it was kinda crap); After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott – a poetry pamphlet

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints,) Carcanet (15), Bloomsbury & Faber (12 each), Alice James Books & Picador/Pan Macmillan (9 each)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year: Sherman Alexie and Bernardine Bishop

Proudest bookish achievements: Reading almost the entire Carol Shields Prize longlist; seeing The Bookshop Band on their huge Emerge, Return tour and not just getting my photo with them but having it published on both the Foreword Reviews and Shelf Awareness websites

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Getting a chance to judge published debut novels for the McKitterick Prize

Books that made me laugh: Lots, but particularly Fortunately, the Milk… by Neil Gaiman, The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs, and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse

Books that made me cry: On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Best book club selections: Clear by Carys Davies, Howards End by E.M. Forster, Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

Best first lines encountered this year:

- From Cocktail by Lisa Alward: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.”

- From A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg: “Oh, the games families play with each other.”

- From The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”- From Mammoth by Eva Baltasar: “May I know to be alert when, at the stroke of midnight, life sends me its cavalry.”

- From Private Rites by Julia Armfield: “For now, they stay where they are and listen to the unwonted quiet, the hush in place of rainfall unfamiliar, the silence like a final snuffing out.”

- From Come to the Window by Howard Norman: “Wherever you sit, so sit all the insistences of fate. Still, the moment held promise of a full life.”

- From Intermezzo by Sally Rooney: “It doesn’t always work, but I do my best. See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

- From Barrowbeck by Andrew Michael Hurley: “And she thought of those Victorian paintings of deathbed scenes: the soul rising vaporously out of a spent and supine body and into a starry beam of light; all tears wiped away, all the frailty and grossness of a human life transfigured and forgiven at last.”

- From Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: “Pure life.”

Books that put a song in my head every time I picked them up: I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill (“Crash” by Dave Matthews Band); Y2K by Colette Shade (“All Star” by Smashmouth)

Shortest book titles encountered: Feh (Shalom Auslander) and Y2K (Colette Shade), followed by Keep (Jenny Haysom)

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best book titles from other years: Recipe for a Perfect Wife, Tripping over Clouds, Waltzing the Cat, Dressing Up for the Carnival, The Met Office Advises Caution

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol

Best punning title (and nominative determinism): Knead to Know: A History of Baking by Dr Neil Buttery

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

A couple of 2024 books that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, You Are Here by David Nicholls

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The downright strangest books I read this year: Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, followed by The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman. All Fours by Miranda July (I am at 44% now) is pretty weird, too.

My Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Like many bloggers and other book addicts, I’m irresistibly drawn to the new books released each year. However, I consistently find that many memorable reads were published earlier. A few of these are from 2022 or 2023 and most of the rest are post-2000; the oldest is from 1910. These 14 selections (alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order), together with my Best of 2024 post coming up on Tuesday, make up about the top 10% of my year’s reading. Repeated themes included adolescence, parenting (especially motherhood) and trauma. The two not pictured below were read electronically.

Fiction

Fun facts:

- I read 4 of these for book club (Forster, Mandel, Munro and Obreht)

- 3 (Mandel, McEwan and Obreht) were rereads

- I read 2 as part of my Carol Shields Prize shadowing (Foote and Zhang)

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie: Groundbreaking for both Indigenous literature and YA literature, this reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior moves to a white high school and soon becomes adept at code-switching (and cartooning). Heartfelt; spot on.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop: A low-key ensemble story about the residents of one London street: a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait; their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love. Beyond the secrets, threats and climactic moments is the reassuring sense that neighbours will be there for you. Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. A great discovery.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote: Is this family memoir? Or autofiction? Foote draws on personal stories but also invokes overarching narratives of Black migration and struggle. The result is magisterial, a debut that is like oral history and a family scrapbook rolled into one, with many strong female characters. Like a linked story collection, it pulls together 15 vignettes from 1916 to 1989 and told in different styles and voices, including AAVE. The inherited trauma is clear, yet Foote weaves in counterbalancing lightness and love.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Howards End by E.M. Forster: Rereading for book club, I was so impressed by its complexities – the illustration of class, the character interactions, the coincidences, the deliberate doublings and parallels. It covers so many issues, always without a heavy touch. So many sterling sentences: depictions of places, observations of characters, or maxims that are still true of life. Well over a century later and the picture of well-meaning wealthy intellectuals’ interference making others’ lives worse is just as cutting.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Reproduction by Louisa Hall: Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring. It’s a recognisable piece of autofiction, with a sublime clarity as life is transcribed to the page exactly as it was lived. A tale of transformation – chosen or not – and peril in a country hurtling toward self-implosion. Brilliantly envisioned.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel: This has persisted as a definitive imagination of post-apocalypse life. On a reread, I was captivated by the different layers of the nonlinear story, from celebrity gossip to a rare graphic novel series, and the links between characters and storylines. Mandel also seeds subtle connections to later work. Themes that struck me were the enduring power of art and the value of the hyperlocal. It seems prescient of Covid-19, but more so of climate collapse. An ideal blend of the literary and the speculative.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan: A perfect novella. Its core is the July 1962 night when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about them – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early work, but quiet, hinging on the smallest action, the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Beggar Maid by Alice Munro: Linked short stories about a hardscrabble upbringing in small-town Ontario and a woman’s ongoing search for love. Rose’s stepmother Flo is resentful and stingy. She feels she’s always been hard done by, and takes it out on Rose. From early on, we know Rose makes it out of West Hanratty and gets a chance at a larger life, that her childhood becomes a tale of deprivation. Each story is intense, pitiless, and practically as detailed as an entire novel. Rich in insight into characters’ psychology.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht: Natalia, a medical worker in a war-ravaged country, learns of her grandfather’s death away from home. The only one who knew the secret of his cancer, she sneaks away from an orphanage vaccination program to reclaim his personal effects, hoping they’ll reveal something about why he went on this final trip. On this reread I was utterly entranced, especially by the sections about The Deathless Man. I had forgotten the medical element, which of course I loved. My favourite Women’s Prize winner.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang: On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy anything. The 29-year-old Chinese American chef’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals. Her relationship with her employer’s 21-year-old daughter is a passionate secret. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. A striking picture of desire at the end of the world.

Nonfiction

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood by Lucy Jones: A potent blend of scientific research and stories from the frontline. Jones synthesizes a huge amount of information into a tight narrative structured thematically but also proceeding chronologically through her own matrescence. The hybrid nature of the book is its genius. There’s a laser focus on her physical and emotional development, but the statistical and theoretical context gives a sense of the universal. For anyone who’s ever had a mother.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer: Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him his melanoma was back. Tests revealed metastases everywhere, including in his brain. The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday. His prose is a just right match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud: A travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles. But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a topographical reality. Growing up with a violent Pakistani father and passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option in fight-or-flight situations. A childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD. Her portrayals of sites and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant. Geography, history and social justice are a backdrop for a stirring personal story.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: True to her background in acting and directing, the book is based around scenes and dialogue, and present-tense narration mimics her viewpoint starting at age six. Much imaginative work was required to make her chaotic late-1990s California household, presided over by a hoarding Mormon cancer survivor, feel real. Abuse, eating disorders, a paternity secret: The mind-blowing revelations keep coming. So much is sad. And yet it’s a very funny book in its observations and turns of phrase.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

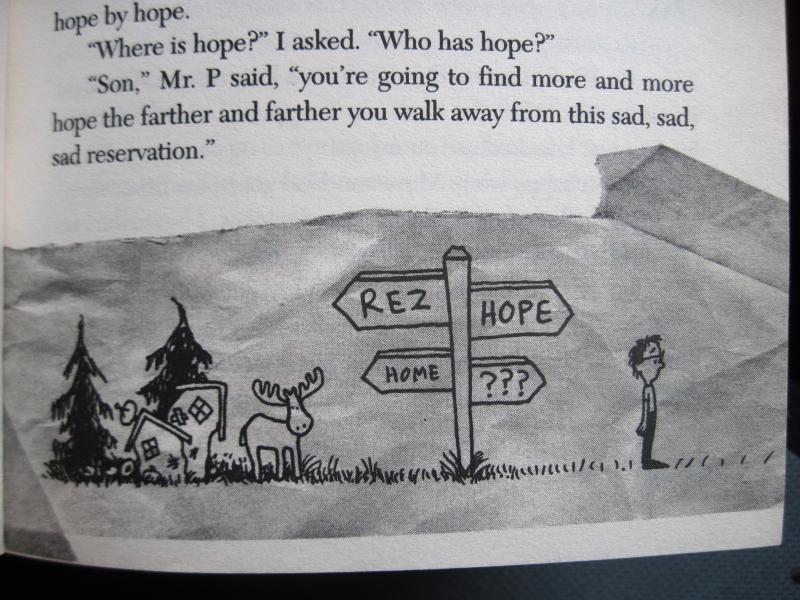

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

There are 22 stories in this fairly short book, so most top out at no more than 10 pages: little slices of life on and around the reservation at Spokane, Washington. Some central characters recur, such as Victor, Thomas Builds-the-Fire and James Many Horses, but there are so many tales that I couldn’t keep track of them across the book even though I read it quickly. My favourite was “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona,” in which Victor and Thomas fly out to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Some of the longer titles give a sense of the tone: “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” and “Jesus Christ’s Half-Brother Is Alive and Well on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” I couldn’t help but think of it as a so-so rehearsal for

There are 22 stories in this fairly short book, so most top out at no more than 10 pages: little slices of life on and around the reservation at Spokane, Washington. Some central characters recur, such as Victor, Thomas Builds-the-Fire and James Many Horses, but there are so many tales that I couldn’t keep track of them across the book even though I read it quickly. My favourite was “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona,” in which Victor and Thomas fly out to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Some of the longer titles give a sense of the tone: “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” and “Jesus Christ’s Half-Brother Is Alive and Well on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” I couldn’t help but think of it as a so-so rehearsal for  The title story is about Mary Toft – I thought of making her hoax the subject of a Three on a Theme post because I actually have two novels about her downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss (Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer), but the facts as conveyed here don’t seem like nearly enough to fuel a whole book, so I doubt I’ll read those. Donoghue has a good eye for historical curios and incidents and an academic’s gift for research, yet not many of these 17 stories, most of which are in the third person, rise above the novelty. Many protagonists are British or Irish women who were a footnote in the historical record: an animal rights activist, a lord’s daughter, a cult leader, a blind poet, a medieval rioter, a suspected witch. There are mild homoerotic touches, too. I enjoyed “Come, Gentle Night,” about John Ruskin’s honeymoon, and “Cured,” which reveals a terrifying surgical means of controlling women’s moods but, as I found with Astray and Learned by Heart, Donoghue sometimes lets documented details overwhelm other elements of a narrative. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

The title story is about Mary Toft – I thought of making her hoax the subject of a Three on a Theme post because I actually have two novels about her downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss (Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer), but the facts as conveyed here don’t seem like nearly enough to fuel a whole book, so I doubt I’ll read those. Donoghue has a good eye for historical curios and incidents and an academic’s gift for research, yet not many of these 17 stories, most of which are in the third person, rise above the novelty. Many protagonists are British or Irish women who were a footnote in the historical record: an animal rights activist, a lord’s daughter, a cult leader, a blind poet, a medieval rioter, a suspected witch. There are mild homoerotic touches, too. I enjoyed “Come, Gentle Night,” about John Ruskin’s honeymoon, and “Cured,” which reveals a terrifying surgical means of controlling women’s moods but, as I found with Astray and Learned by Heart, Donoghue sometimes lets documented details overwhelm other elements of a narrative. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)  Hard to convey the variety of this 20-story anthology in a concise way because they run the gamut from realist (Nigerian homosexuality in “Happy Is a Doing Word” by Arinze Ifeakandu; Irish gangsters in “The Blackhills” by Eamon McGuinness) to absurd (Ling Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Catherine Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal; “Ira and the Whale” is Rachel B. Glaser’s gay version of the Jonah legend). Also difficult to encapsulate my reaction, because for every story I would happily have seen expanded into a novel (the gloomy character study “The Locksmith” by Grey Wolfe LaJoie, the teenage friends’ coming-of-age in “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool” by the marvellous Kirstin Valdez Quade), there was another I thought might never end (“Dream Man” by Cristina Rivera-Garza and “Temporary Housing” by Kathleen Alcott). Three are in translation. I admired Lisa Taddeo’s tale of grief and revenge, “Wisconsin,” and Naomi Shuyama-Gómez’s creepy Colombian-set “The Commander’s Teeth.” But my two favourites were probably “Me, Rory, and Aurora” by Jonas Eika (Danish), which combines an uneasy threesome, the plight of the unhoused and a downright chilling Ishiguro-esque ending; and “Xífù,” K-Ming Chang’s funny, morbid take on daughter/mother-in-law relations in China. (PDF review copy)

Hard to convey the variety of this 20-story anthology in a concise way because they run the gamut from realist (Nigerian homosexuality in “Happy Is a Doing Word” by Arinze Ifeakandu; Irish gangsters in “The Blackhills” by Eamon McGuinness) to absurd (Ling Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Catherine Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal; “Ira and the Whale” is Rachel B. Glaser’s gay version of the Jonah legend). Also difficult to encapsulate my reaction, because for every story I would happily have seen expanded into a novel (the gloomy character study “The Locksmith” by Grey Wolfe LaJoie, the teenage friends’ coming-of-age in “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool” by the marvellous Kirstin Valdez Quade), there was another I thought might never end (“Dream Man” by Cristina Rivera-Garza and “Temporary Housing” by Kathleen Alcott). Three are in translation. I admired Lisa Taddeo’s tale of grief and revenge, “Wisconsin,” and Naomi Shuyama-Gómez’s creepy Colombian-set “The Commander’s Teeth.” But my two favourites were probably “Me, Rory, and Aurora” by Jonas Eika (Danish), which combines an uneasy threesome, the plight of the unhoused and a downright chilling Ishiguro-esque ending; and “Xífù,” K-Ming Chang’s funny, morbid take on daughter/mother-in-law relations in China. (PDF review copy)  The novel-in-stories is about Lucy, a photographer in her early thirties with a penchant for falling for the wrong men – alcoholics or misogynists or ones who aren’t available. When she’s not working she’s thrill-seeking: rafting in Colorado, travelling in the Amazon, sailing in the Caribbean, or gliding. “Everything good I’ve gotten in life I’ve gotten by plunging in,” she boasts, to which a friend replies, “Sure, and everything bad you’ve gotten in your life you’ve gotten by plunging in.” Ultimately she ‘settles down’ on the Colorado ranch she inherits from her grandmother with a dog, making this – based on what I learned from the autobiographical essays in

The novel-in-stories is about Lucy, a photographer in her early thirties with a penchant for falling for the wrong men – alcoholics or misogynists or ones who aren’t available. When she’s not working she’s thrill-seeking: rafting in Colorado, travelling in the Amazon, sailing in the Caribbean, or gliding. “Everything good I’ve gotten in life I’ve gotten by plunging in,” she boasts, to which a friend replies, “Sure, and everything bad you’ve gotten in your life you’ve gotten by plunging in.” Ultimately she ‘settles down’ on the Colorado ranch she inherits from her grandmother with a dog, making this – based on what I learned from the autobiographical essays in  McCracken is terrific in short forms:

McCracken is terrific in short forms:  Compared to

Compared to  These 44 stories, mostly of flash fiction length, combine the grit of Denis Johnson with the bite of Flannery O’Connor. Siblings squabble over a late parent’s effects or wishes, marriages go wrong, the movie business isn’t as glittering as it’s cracked up to be, and drugs and alcohol complicate everything. The settings range through North America and the Caribbean, with a couple of forays to Europe. There are no speech marks and, whether the narrative is in first person or third, all the voices are genuine and distinctive yet flow together admirably. Svoboda has a poet-like talent for compact, zingy lines; two favourites were “my laziness is born of generalized-looking-to-get-specific grief, like an atom trying to make salt” (“Niagara”) and “Ditziness, a kind of Morse code of shriek-and-stop, erupts around the girls” (“Orphan Shop”).

These 44 stories, mostly of flash fiction length, combine the grit of Denis Johnson with the bite of Flannery O’Connor. Siblings squabble over a late parent’s effects or wishes, marriages go wrong, the movie business isn’t as glittering as it’s cracked up to be, and drugs and alcohol complicate everything. The settings range through North America and the Caribbean, with a couple of forays to Europe. There are no speech marks and, whether the narrative is in first person or third, all the voices are genuine and distinctive yet flow together admirably. Svoboda has a poet-like talent for compact, zingy lines; two favourites were “my laziness is born of generalized-looking-to-get-specific grief, like an atom trying to make salt” (“Niagara”) and “Ditziness, a kind of Morse code of shriek-and-stop, erupts around the girls” (“Orphan Shop”).  I’d only ever read The Color Purple, so when I spotted this in a bookshop on our Northumberland holiday it felt like a good excuse to try something else by Walker. I had actually encountered one of the stronger stories before: “Everyday Use” is in the

I’d only ever read The Color Purple, so when I spotted this in a bookshop on our Northumberland holiday it felt like a good excuse to try something else by Walker. I had actually encountered one of the stronger stories before: “Everyday Use” is in the

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.