Hurled into Gettysburg: Poems by Theresa Wyatt

Today marks the start of the 155th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place on July 1–3, 1863. Theresa Wyatt was so kind as to send her terrific book of commemorative poems all the way to England for me. She pays tribute to forgotten and fringe players of the Civil War, such as Elizabeth C. Thorn, who served as the gatekeeper of Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery from 1862 to 1865 while her husband was off fighting, and Jennie Wade, the only civilian killed by a war sniper. “Jennie & Jack” includes fragments of letters written by Jennie and her childhood friend and sweetheart Johnston Skelly, who died of an infection just nine days after her; neither was aware of the other’s demise. Another great story is that of poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier, whose colorblindness may have been a disadvantage growing up on a farm but was a metaphorical boon in the days of slavery.

Today marks the start of the 155th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place on July 1–3, 1863. Theresa Wyatt was so kind as to send her terrific book of commemorative poems all the way to England for me. She pays tribute to forgotten and fringe players of the Civil War, such as Elizabeth C. Thorn, who served as the gatekeeper of Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery from 1862 to 1865 while her husband was off fighting, and Jennie Wade, the only civilian killed by a war sniper. “Jennie & Jack” includes fragments of letters written by Jennie and her childhood friend and sweetheart Johnston Skelly, who died of an infection just nine days after her; neither was aware of the other’s demise. Another great story is that of poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier, whose colorblindness may have been a disadvantage growing up on a farm but was a metaphorical boon in the days of slavery.

The poems are also peopled by immigrant settlers, Underground Railroad passengers (“divinity squeezing / into dark tight spaces”) on the run from slave hunters, and brothers fighting on opposite sides. On a recent visit to Gettysburg Wyatt imagines herself into the position of General Buford, “descending these stairs in flawless summer light, / uplifted by a cyclorama of clear view, fortified” – a clever reference to the famous Gettysburg Cyclorama.

In “Visiting Gettysburg” she captures the sense of overwhelmed helplessness one experiences in relation to great historical tragedies: “trying to take it all in as if I knew anything at all / about horses, cannons or bloodshed.” The imagery ranges from grisly through innocuous to lovely, so that “buckets full of gangrene – a country’s highest price” contrast with “drops of ruby blood / invisible to sight or touch / [that] have mingled into blooms” on a farm that once comprised part of the battlefield. Especially if you’ve visited Gettysburg or another military site recently, you’ll find these poems truly resonate. It’s hard not to devour them within one sitting.

Another favorite passage: “Some people like their heroes loud / and let them talk, but sometimes history / picks off the scabs of arrogance / when setting records straight.” (from “At the Jennie Wade Monument”)

Readalikes:

March by Geraldine Brooks

Into the Cyclorama by Annie Kim

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Blog Tour: The Floating Theatre by Martha Conway (Review & Excerpt)

The Floating Theatre, Martha Conway’s fourth novel, opens with a bang – literally. April 1838: twenty-two-year-old seamstress May Bedloe and her cousin, the actress Comfort Vertue, are on the St. Louis-bound steamboat Moselle when its boilers explode (a real-life disaster) and they must evacuate posthaste. Afterwards Comfort accepts a new role giving abolitionist speeches; May takes her sewing skills on board Captain Hugo Cushing’s Floating Theatre, where she will be a Jill of all trades: repairing costumes, printing tickets, publicizing the show in towns along the Ohio River where they moor for performances, and so on.

Conway gives a vivid sense of nineteenth-century theater life, both off-stage and on-, including just the right amount of historical detail so you can picture everything that’s going on. May is a delightfully no-nonsense narrator – she’d probably be diagnosed with Asperger’s nowadays for her literal approach and her initial inability to lie – and she’s supported by a wonderfully Dickensian cast of actors and crew members. The gripping plot takes on a serious dimension as May, too, gets drawn into the abolition movement: soon she’s helping to deliver runaway slaves from one side of the river to freedom on the other.

Conway gives a vivid sense of nineteenth-century theater life, both off-stage and on-, including just the right amount of historical detail so you can picture everything that’s going on. May is a delightfully no-nonsense narrator – she’d probably be diagnosed with Asperger’s nowadays for her literal approach and her initial inability to lie – and she’s supported by a wonderfully Dickensian cast of actors and crew members. The gripping plot takes on a serious dimension as May, too, gets drawn into the abolition movement: soon she’s helping to deliver runaway slaves from one side of the river to freedom on the other.

In America this was published as The Underground River, more clearly advertising its Underground Railroad theme. As it happens, I prefer this to Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, a novel to which it will inevitably be compared. (For one thing, Conway has a much more nuanced slave catcher character.) This is terrific historical fiction I can heartily recommend.

My rating:

The Floating Theatre was released in the UK by Zaffre, an imprint of Bonnier Publishing, on June 15th. My thanks to Imogen Sebba for the free copy for review.

An exclusive extract from The Floating Theatre:

Two figures were standing on the lower deck at the stern of the boat. One of them might have been Hugo, but as I got closer I saw that the other one was certainly not Helena—it was Thaddeus Mason, eating popcorn from a red-and-white striped bag.

“What ho, May!” Thaddeus called out when he saw me, as if he were practicing for a nautical part. I noticed he no longer wore his arm in a sling. The other man turned as I came up the gangplank; like Thaddeus, he wore his hair long, but his coloring was darker and he was half a head taller. There was a band of black crepe around his straw hat, and his shirtsleeves were rolled up past his elbows. Thaddeus introduced me.

“Captain Hugo Cushing,” the man said in a British accent, touching his hat.

“May and I were on the Moselle together,” Thaddeus told him—was that to be his introduction for me from now on? But he went on to say that Hugo’s sister Helena had been on the Moselle, too. “Do you remember the singer at dinner? Helena Cushing, of Hugo and Helena’s Floating Theatre?” Thaddeus took off his hat. “Sadly, she was not as fortunate as we were.”

I looked at Hugo and tried to think of something kind to say. I remembered the singer in her pink dress with the light shining behind her.

“The captain let her on to perform,” Hugo said. “We often made a few extra dollars this way. She was going to get off at the stop after Fulton. I was just pushing off to meet up with her there when the sky broke up with the explosion.”

“Oh,” I said. “That is—that’s very bad…” I trailed off awkwardly, but Thaddeus came in with a string of platitudes, which he spoke with great conviction and aplomb—a terrible disaster, an immense misfortune, the captain was a dastardly fellow.

“Where do you go?” I asked Hugo when Thaddeus finished. “Or do you stay here?”

He looked at me blankly.

“On this boat. Your theatre. Where do you perform?”

“Oh, well then, down along the Ohio, of course. We dock at a different town every day, put on a show, and then the next morning pull up and head for the next town. We go all the way to the Mississippi playing towns until the weather turns. Then we get pushed back up the river—I hire a steamer.” I could see that his boat, a flatboat, had no steam power of its own. “Fourth year at it,” he told me. “My sister and I put it all together. But now…” He made a gesture which I took to understand that for him, like me, his old partnership was over.

“And if that weren’t enough, his boat was damaged by the explosion,” Thaddeus added. “The captain was just telling me. Part of the Moselle’s paddle box shot in like a cannonball.”

“Even worse, my leather boat pump got punctured,” Hugo said. “Don’t know how I’m going to fix it, and a new one costs twenty dollars more than I have.”

“How much does a new one cost?” I asked.

He looked at me as if I were a fool. “Twenty dollars.”

“Where is your company?” Thaddeus asked him. “Maybe you could take up a collection.”

“They skittered off into town. Probably drinking their way into even more uselessness. Damn actors. Excuse me,” he said, but I wasn’t sure he meant the apology for me since he was looking out at the river. I wasn’t offended in any case. I had seen actors humiliate themselves in a variety of ways over the years.

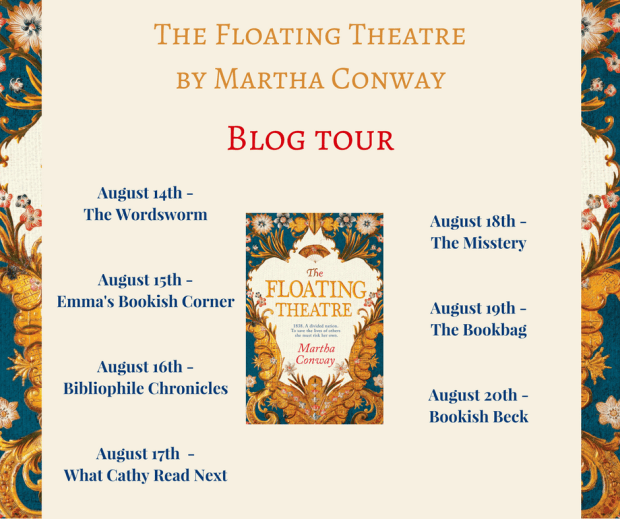

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the blog tour for The Floating Theatre. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared.

Nancy appeals to the Colberts’ adult daughter, Rachel Blake, to accompany her on her walks so that Martin will not “overtake” her in the woods. Although none of the white characters take the repeated threat of attempted rape seriously enough, Henry and Rachel do eventually help Nancy escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. When Sapphira realizes her ‘property’ has been taken from her, she informs Rachel she is now persona non grata, but changes her mind when illness brings tragedy into Rachel’s household.

Nancy appeals to the Colberts’ adult daughter, Rachel Blake, to accompany her on her walks so that Martin will not “overtake” her in the woods. Although none of the white characters take the repeated threat of attempted rape seriously enough, Henry and Rachel do eventually help Nancy escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. When Sapphira realizes her ‘property’ has been taken from her, she informs Rachel she is now persona non grata, but changes her mind when illness brings tragedy into Rachel’s household. Published when Thomas was in his mid-twenties, this is a series of 10 sketches, some of which are more explicitly autobiographical (as in first person, with a narrator named Dylan Thomas) than others. There is a rough chronological trajectory to the stories, with the main character a mischievous boy, then a grandstanding teenager, then a young journalist in his first job. The countryside and seaside towns of South Wales recur as settings, and – as will be no surprise to readers of Under Milk Wood – banter-filled dialogue is the priority. I most enjoyed the childhood japes in the first two pieces, “The Peaches” and “A Visit to Grandpa’s.” The rest failed to hold my attention, but I marked out two long passages that to me represent the voice and scene-setting that the Dylan Thomas Prize is looking for. The latter is the ending of the book and reminds me of the close of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” (University library)

Published when Thomas was in his mid-twenties, this is a series of 10 sketches, some of which are more explicitly autobiographical (as in first person, with a narrator named Dylan Thomas) than others. There is a rough chronological trajectory to the stories, with the main character a mischievous boy, then a grandstanding teenager, then a young journalist in his first job. The countryside and seaside towns of South Wales recur as settings, and – as will be no surprise to readers of Under Milk Wood – banter-filled dialogue is the priority. I most enjoyed the childhood japes in the first two pieces, “The Peaches” and “A Visit to Grandpa’s.” The rest failed to hold my attention, but I marked out two long passages that to me represent the voice and scene-setting that the Dylan Thomas Prize is looking for. The latter is the ending of the book and reminds me of the close of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” (University library)