Winter Reading, Part II: “Snow” Books by Coleman, Rice & Whittell

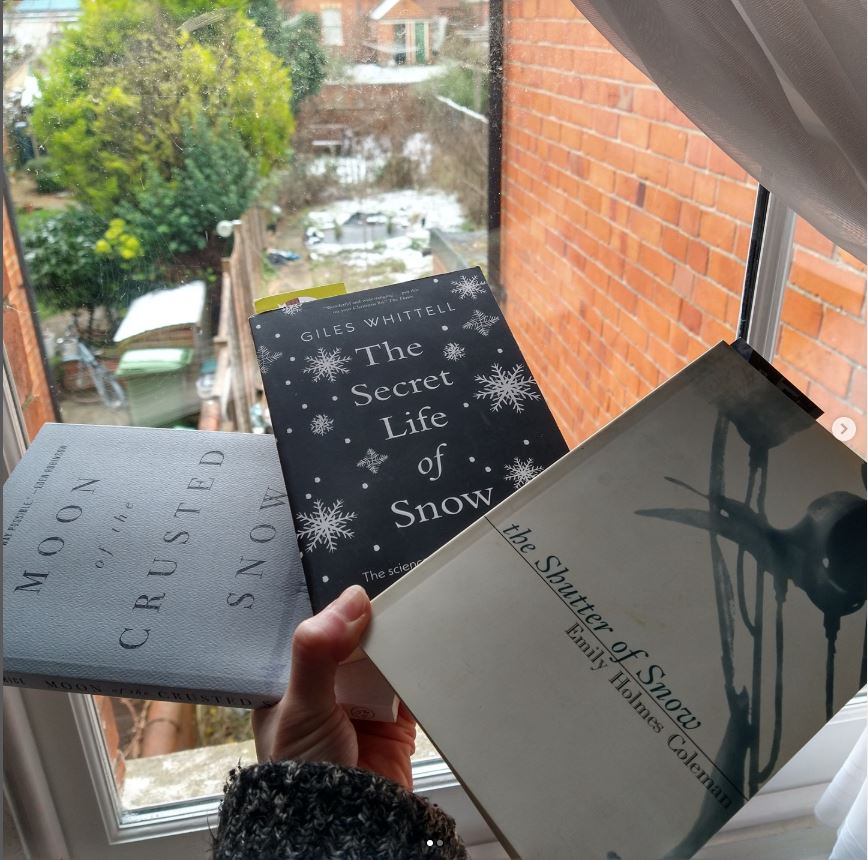

Here I am squeaking in on the day before the spring equinox – when it’s predicted to be warmer than Ibiza here in southern England, as headlines have it – with a few snowy reads that have been on my stack for much of the winter. I started reading this trio when we got a dusting back in January, in case (as proved to be true) it was our only snow of the year. I have an arresting work of autofiction that recreates a period of postpartum psychosis, a mildly dystopian novel by a First Nations Canadian, and a snow-lover’s compendium of science and trivia.

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

Snow had an unreality to it. Was this because of its pace or its beauty? There was an accompanying clarity to snow as well, especially snow, drifting snow. What was and wasn’t important were made distinct. Certain facts became chillingly apparent. Pain, for one.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman (1930)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (2018)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) ![]()

The Secret Life of Snow: The science and the stories behind nature’s greatest wonder by Giles Whittell (2018)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Whittell’s mention of the U.S. East Coast “Snowmaggedon” of February 2010 had me digging out photos my mother sent me of the aftermath at our family home of the time.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately? Or is it looking like spring?

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent

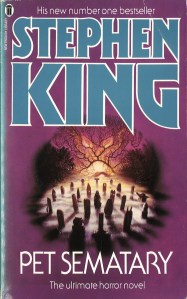

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent  I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.