Today is PKD Awareness Day. Because the author and I both have polycystic kidney disease, I’m doing something I rarely do and reprinting an early review of mine that has already appeared on Shelf Awareness. I could hardly believe it when I was trawling through the list of review book offers and saw that Eiren Caffall also has PKD, then even more astonished to learn that it is a major theme in her memoir, which also weaves in marine biology and environmental concerns. An altogether intriguing book that, of course, held personal interest for me.

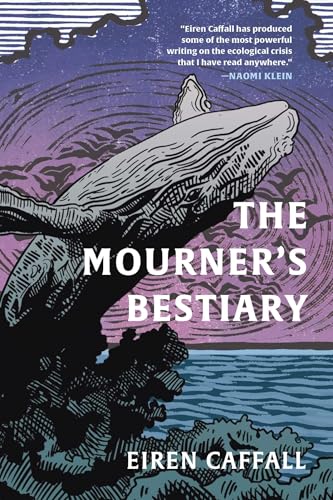

The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall

Eiren Caffall’s debut is an ardent elegy for her illness-haunted family and for the ailing marine environments that inspire her.

For centuries, the author’s family has been subject to “the Caffall Curse.” Polycystic kidney disease, a degenerative genetic condition, causes fluid-filled cysts to proliferate in a person’s enlarged kidneys. PKD can involve pain, fatigue, high blood pressure, kidney failure, and a heightened risk of brain aneurysm. Given Caffall’s paternal family history, she expected to die before age 50.

Caffall’s melancholy memoir spotlights moments that opened her eyes to medical and environmental catastrophe. In 1980, when she was nine years old, she and her parents vacationed at a rental cottage on Long Island Sound. They nicknamed the pollution-ridden site “Dogshit Beach”—her mother spent idyllic summers there as a child, yet now “both the ecosystem and my father were slipping away.” For the first time, Caffall became aware of her father’s suffering and lack of energy. She realized that she, too, might have inherited PKD and could face similar struggles as an adult.

Caffall’s melancholy memoir spotlights moments that opened her eyes to medical and environmental catastrophe. In 1980, when she was nine years old, she and her parents vacationed at a rental cottage on Long Island Sound. They nicknamed the pollution-ridden site “Dogshit Beach”—her mother spent idyllic summers there as a child, yet now “both the ecosystem and my father were slipping away.” For the first time, Caffall became aware of her father’s suffering and lack of energy. She realized that she, too, might have inherited PKD and could face similar struggles as an adult.

In 2014, Caffall, then a single mother, took her nine-year-old son, Dex, on vacation to the Gulf of Maine. During the trip, she had a fall that prompted a seizure, and she and Dex were evacuated from Monhegan Island by Coast Guard ship. Although no further seizures ensued and no clear cause emerged, the crisis served as a wake-up call, reminding her of how serious PKD is and that it might afflict her son as well.

The book draws fascinating connections between personal experiences and ecological threats. Caffall structures her story as a gallery of endangered marine animals such as the Longfin Inshore Squid and Humpback Whale, tracing their history and exposing the dangers they face in degraded environments. Red tides (massive algal blooms) and floods are apt metaphors for physical trials: “the Sound was dying, hypoxic … from an overwhelm of nutrients flooding an ecosystem—nitrogen, phosphorus, imbalanced saline—the same things that overwhelm a body when kidneys can no longer filter blood properly.”

Re-created scenes enliven accounts of family illness and therapeutic developments. The lyrical hybrid narrative, informed by scientific journals and government publications, is as impassioned about restoring the environment as it is about ensuring equality of access to health care. Personal and species extinction are just cause for “permanent mourning,” Caffall writes, but adapting to change keeps hope alive.

(Coming out in the USA from Row House Publishing on October 15th)

Posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

[I couldn’t help but compare family members’ trajectories. Like her father, my mother was on dialysis for a time before getting a transplant, from her cousin. Like her aunt, my uncle died of a brain aneurysm, which is an associated risk. It sounds like Caffall has been much more severely affected than I have thus far. She is 53 and on Tolvaptan, a cutting-edge drug that slows the growth of cysts and thus the decline in kidney function. But even within families, the disease course is so varied. A cousin of mine was in her thirties when she had a transplant, whereas I am still very much in the early stages.]

A shout-out to the PKD Foundation in the States and the PKD Charity here in the UK.

A related post: In 2017 I reviewed four books for World Kidney Day.

From the supermarket last week: a plum that wanted to be a kidney.

Ah I’m sorry to hear this Rebecca, I knew you had an inherited kidney disease but not what it was. I’m glad to hear you are, so far, less severely affected than others with PKD. The Caffall sounds really good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No need to be sorry; most days I forget I have it! I’m down to annual check-ups at the local hospital, which just involve some routine bloodwork and monitoring my blood pressure. I know how lucky I am that it’s not more serious.

Despite not having children, I’m invested in society not collapsing through climate breakdown so that there will still be organ transplantation and anti-rejection drugs available if I need them 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds really good, and you know I am always here for more literature that opens up the worlds of chronic illness, especially hereditary ones. I like the comparison Caffall draws between things that threaten the marine environment and things that threaten her internal, bodily one; it’s a neat representation of the ways in which human and world are not separate spheres, at all.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve never really thought of myself as chronically ill, but in the demographic questions for the Emerging Writer application, their description made me think, huh, I do actually tick yes to that.

The ecology content edged towards more than I needed, but her connections worked.

LikeLike

It’s odd, isn’t it—I didn’t think of myself as disabled, and didn’t even know the phrase “chronic illness”, for decades. It just enraged me when people called T1D a “disease”—still does, because it isn’t; it doesn’t have a pathology or an infection vector. But claiming a disabled identity was a bit of a long journey. It’s been nothing but positive for me to have it, though; it makes sense of some things about my experience of the world that didn’t make sense before I claimed that identity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t know about your health issues. Good luck with your on-going treatment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No treatment thus far apart from a daily blood pressure-regulating tablet. How lucky I’ve been!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Long may it continue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A beautiful review, and thank you for your honesty around your condition. Wishing you all the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. The history in my family goes back to my maternal grandmother; beyond that we have no record. My mother was always very open about it. There are so many great resources and support systems out there these days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a thoughtful review Rebecca x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing, Rebecca–long may that early stage last, if a cure isn’t found.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds good. Thank you for sharing your experience and I am very glad that your condition is in the early stages and that you are doing well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful to find your condition reflected in a book (better when you’re knowledgeable about it like you are than just finding out, though, I would guess). I don’t think I’ve come across my most notable affliction of endometriosis in a book; then again, would I WANT to read a book featuring it??? Long may you stay in the early stages and so well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh there are loads of endometriosis references out there, though most of them are in medical memoirs (which I know you don’t tend to read). In fiction, a notable one is in Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting tho I’ve never fancied hers. I just transcribed her for the New Statesman. Picked up an endo reference in Cyndi Lauper’s memoir as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What perfect themes to unite here in this memoir, and what a fine job you’ve done of presenting them. I also love your plum photo. Stay well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] 41 I do long for my own bed on any stay away from home. It’s partly a matter of accepting that chronic illness means I will have limitations. Much as we wanted to do the right thing by not driving, travelling […]

LikeLike