January Novels by Alix E. Harrow & Patricia Highsmith

The month of January was named for the Roman god Janus, known for having two faces: one looking backward, the other forward. “He presided not over one particular domain but over the places between – past and present, here and there, endings and beginnings,” as Alix E. Harrow writes. In her novel, the door is a prevailing metaphor for liminal times and spaces; Highsmith’s work, too, focuses on the way life often pivots on tiny accidents or decisions.

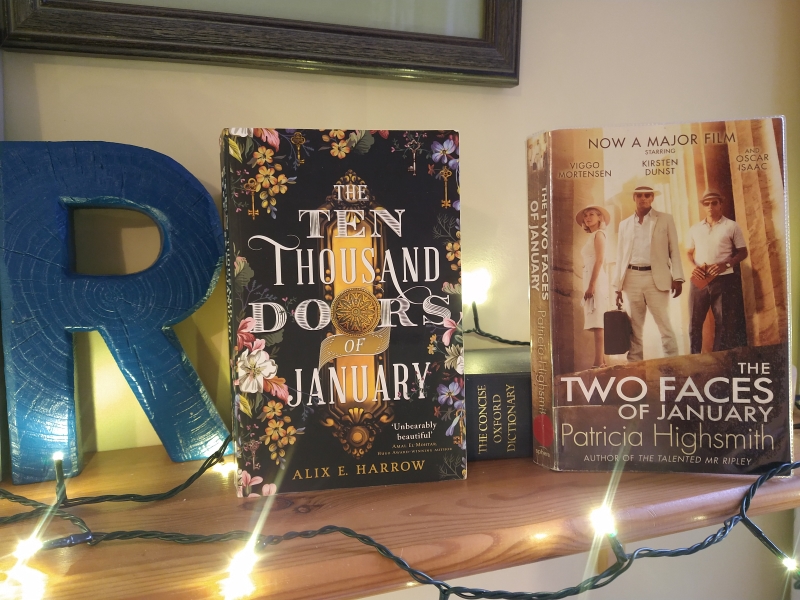

The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E. Harrow (2019)

“I didn’t want to be safe … I wanted to be dangerous, to find my own power and write it on the world.”

As the mixed-race ward of a wealthy collector, January Scaller grows up in a Vermont mansion with a dual sense of privilege and loss. She barely sees her brown-skinned father, who travels the world amassing treasures for Mr. Locke and his archaeological society; and her mother’s absence is an unexplained heartbreak. But when her father also disappears in 1911 – to be apparently replaced by an African governess named Jane Irimu (it’s her quote above) and an enticing scholarly manuscript entitled The Ten Thousand Doors – 17-year-old January discovers the power of words to literally open doors to new worlds, and sets off on a quest to reunite her family. At every turn, though, she’s thwarted by evil white men who, after plundering foreign cultures, intend to close the doors of opportunity behind them.

As the mixed-race ward of a wealthy collector, January Scaller grows up in a Vermont mansion with a dual sense of privilege and loss. She barely sees her brown-skinned father, who travels the world amassing treasures for Mr. Locke and his archaeological society; and her mother’s absence is an unexplained heartbreak. But when her father also disappears in 1911 – to be apparently replaced by an African governess named Jane Irimu (it’s her quote above) and an enticing scholarly manuscript entitled The Ten Thousand Doors – 17-year-old January discovers the power of words to literally open doors to new worlds, and sets off on a quest to reunite her family. At every turn, though, she’s thwarted by evil white men who, after plundering foreign cultures, intend to close the doors of opportunity behind them.

This was an unlikely book for me to pick up: I didn’t get on with that whole wave of books with books and keys on the cover (Bridget Collins et al.) and wouldn’t willingly pick up romantasy – yet this features two meant-to-be romances fought for across worlds and eras. I grow impatient with a book-within-the-book format. But The Chronicles of Narnia, which no doubt inspired Harrow, were my favourite books as a child. Especially early on, I found this as thrilling as The Absolute Book and The End of Mr. Y. Whereas those doorstoppers held my interest all the way through, though, this became a trudge at a certain point. Harrow is maybe a little too pleased with her own imagination and turns of phrase, like T. Kingfisher. (Bad the dog is also in peril far too often.) In the end, this reminded me most of Babel by R.F. Kuang with its postcolonial conscience and words as power. I enjoyed this enough that I think I’ll propose her The Once and Future Witches for book club. (Little Free Library) ![]()

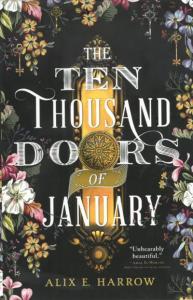

The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith (1964)

Three American vacationers meet in a hotel in Greece one January. But the circumstances are far from auspicious. Conman Chester MacFarland is traveling with his 15-years-younger wife, Colette. Rydal Keener is a stranger who, seemingly on a whim, helps them cover up the accidental death of a Greek police investigator who came to ask Chester some questions. From here on in, they’re in lockstep, moving around Greece together, obtaining fake passports and checking the headlines obsessively to outrun consequences. Colette takes a fancy to Rydal, and the jealousy emanating from the love triangle is complicated by Chester’s alcoholism and Rydal’s hurt over earning a police record for a consensual teenage relationship. I have a dim memory of seeing the 2014 Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen film, but luckily I didn’t recall any major events. A climactic scene takes place at the palace of Knossos, and the chase continues until an unavoidably tragic end.

Three American vacationers meet in a hotel in Greece one January. But the circumstances are far from auspicious. Conman Chester MacFarland is traveling with his 15-years-younger wife, Colette. Rydal Keener is a stranger who, seemingly on a whim, helps them cover up the accidental death of a Greek police investigator who came to ask Chester some questions. From here on in, they’re in lockstep, moving around Greece together, obtaining fake passports and checking the headlines obsessively to outrun consequences. Colette takes a fancy to Rydal, and the jealousy emanating from the love triangle is complicated by Chester’s alcoholism and Rydal’s hurt over earning a police record for a consensual teenage relationship. I have a dim memory of seeing the 2014 Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen film, but luckily I didn’t recall any major events. A climactic scene takes place at the palace of Knossos, and the chase continues until an unavoidably tragic end.

I’ve read several Ripley novels and a few standalone psychological mysteries by Highsmith and enjoyed them well enough, but murders aren’t really my thing. (Carol is the only work of hers that I’ve truly loved.) My specific issue here was with the central trio of characters. Colette is thinly drawn and doesn’t get enough time on the page. Chester seems much older than his 42 years and is an irredeemable swindler. It’s only because of our fondness for Rydal that we want them all to get away with it. But even Rydal doesn’t get the in-depth portrayal one might hope for. There’s the injustice of his backstory and the fact that he’s a would-be poet, true, but we never understand why he helped the MacFarlands, so have to conclude that it was the impulse of a moment and committed him to a regrettable course. This is pacey enough to keep the pages turning, but won’t stick with me. (Public library) ![]()

I’m turning my face forward: Good riddance to January 2026, during which I’ve mostly felt rubbish; here’s hoping for a better rest of the year. I’m off to the opera tonight – something I’ve only done once before, in Leeds in 2006! – to see Susannah, a tale from the Apocrypha transplanted to the 1950s U.S. South.