Reading Ireland Month 2019: Jess Kidd and Jane Urquhart

Last month I picked out this exchange from East of Eden by John Steinbeck:

“But the Irish are said to be a happy people, full of jokes.”

“They’re not. They’re a dark people with a gift for suffering way past their deserving. It’s said that without whisky to soak and soften the world, they’d kill themselves. But they tell jokes because it’s expected of them.”

There’s something about that mixture of darkness and humor, isn’t there? I also find that Irish art (music as well as literature) has a lot of heart. I only read two Ireland-related historical novels this month, but they both have that soulful blend of light and somber. Both:

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd (2019)

In the autumn of 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Problem is, this missing girl is no ordinary child, and collectors of medical curiosities and circus masters alike are interested in acquiring her.

In its early chapters this delightful Victorian pastiche reminded me of a cross between Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith and Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, and that comparison played out pretty well in the remainder. Kidd paints a convincingly gritty picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks: when Bridie first arrived in London from Dublin, she worked as an assistant to a resurrectionist; her maid is a 7-foot-tall bearded lady; and her would-be love interest, if only death didn’t separate them, is the ghost of a heavily tattooed boxer.

Medicine (surgery – before and after anesthesia) and mythology (mermaids and selkies) are intriguing subplots woven through, such that this is likely to appeal to fans of The Way of All Flesh and The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock. Kidd’s prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people (but also in her more expansive musings on the dirty, bustling city): “a joyless string of a woman, thin and pristine with a halibut pout,” “In Dr Prudhoe’s countenance, refinement meets rogue,” and “People are no more than punctuation from above.”

I’ll definitely go back and read Kidd’s two previous novels, Himself and The Hoarder. I didn’t even realize she was Irish, so I’m grateful to Cathy for making me aware of that in her preview of upcoming Irish fiction. [Trigger warnings: violence against women and animals.] (Out from Canongate on April 4th.)

Away by Jane Urquhart (1993)

I was enraptured from the first line: “The women of this family leaned towards extremes” – starting with Mary, who falls in love with a sailor who washes up on the Irish coast in the 1840s amid the cabbages, silver teapots and whiskey barrels of a shipwreck and dies in her arms. Due to her continued communion with the dead man, people speak of her being “away with the fairies,” even after she marries the local schoolteacher, Brian O’Malley.

With their young son, Liam, they join the first wave of emigration to Canada during the Potato Famine, funded by their landlords, the Sedgewick brothers of Puffin Court (amateur naturalist Osbert and poet Granville). No sooner have the O’Malleys settled and had their second child, Eileen, than Mary disappears. As she grows, Eileen takes after her mother, mystically attuned to portents and prone to flightiness, while Liam is a happily rooted Great Lakes farmer. Like Mary, Eileen has her own forbidden romance, with a political revolutionary who dances like a dream.

With their young son, Liam, they join the first wave of emigration to Canada during the Potato Famine, funded by their landlords, the Sedgewick brothers of Puffin Court (amateur naturalist Osbert and poet Granville). No sooner have the O’Malleys settled and had their second child, Eileen, than Mary disappears. As she grows, Eileen takes after her mother, mystically attuned to portents and prone to flightiness, while Liam is a happily rooted Great Lakes farmer. Like Mary, Eileen has her own forbidden romance, with a political revolutionary who dances like a dream.

I’ve been underwhelmed by other Urquhart novels, Sanctuary Line and The Whirlpool, but here she gets it just right, wrapping her unfailingly gorgeous language around an absorbing plot – which is what I felt was lacking in the others. The Ireland and Canada settings are equally strong, and the spirit of Ireland – the people, the stories, the folk music – is kept alive abroad. I recommend this to readers of historical fiction by Margaret Atwood, A.S. Byatt and Hannah Kent.

Some favorite lines:

Osbert says of Mary: “There’s this light in her, you see, and it must not be put out.”

“When summer was finished the family was visited by a series of overstated seasons. In September, they awakened after night frosts to a woods awash with floating gold leaves and a sky frantic with migrating birds – sometimes so great in number that they covered completely with their shadows the acre of light and air that Brian had managed to create.”

“There are five hundred and forty different kinds of weather out there, and I respect every one of them. White squalls, green fogs, black ice, and the dreaded yellow cyclone, just to mention a few.”

It’s my second time participating in Reading Ireland Month, run each March by Cathy of 746 Books and Niall of Raging Fluff.

Did you manage to read any Irish literature this month?

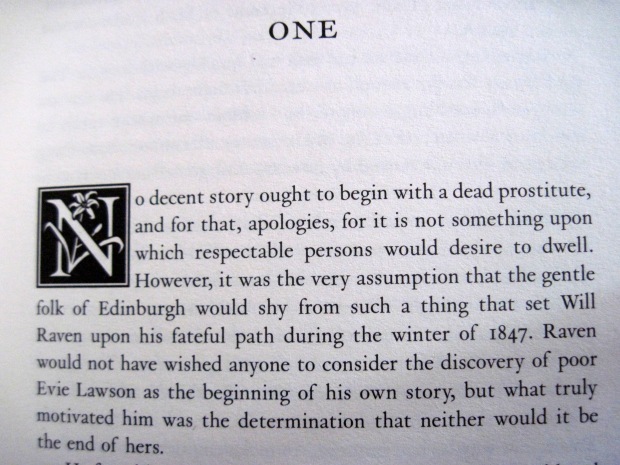

The Way of All Flesh by Ambrose Parry

This historical novel set in Edinburgh in 1847 has one of the best opening paragraphs I’ve come across in a while:

That immediately sets the tone: realistic, sly, and somewhat seedy. If the title sounds familiar, it’s because it’s borrowed from Samuel Butler’s gloomy 1903 meditation on sin and salvation in several generations of a Victorian family. I remember trudging through it on a weekend break to Strasbourg during my year abroad.

Parry (a pseudonym for husband–wife duo Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman) uses the allusion to highlight the hidden sins of the Victorian period and hint at the fleshy concerns of their book, which contains somewhat gruesome scenes of childbirth and surgery. Ether and chloroform were recent introductions and many were still apprehensive about them or even opposed to their use on religious grounds, as Haetzman, a consultant anesthetist, learned while researching for her Master’s degree in the History of Medicine.

Parry (a pseudonym for husband–wife duo Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman) uses the allusion to highlight the hidden sins of the Victorian period and hint at the fleshy concerns of their book, which contains somewhat gruesome scenes of childbirth and surgery. Ether and chloroform were recent introductions and many were still apprehensive about them or even opposed to their use on religious grounds, as Haetzman, a consultant anesthetist, learned while researching for her Master’s degree in the History of Medicine.

Into this milieu enters Will Raven, the new apprentice to Dr. Simpson, a professor of midwifery. Will is troubled by the recent loss of his friend Evie Lawson, the dead prostitute of the first paragraph, and wonders if she could have been poisoned by some bad moonshine. Only as he hears rumors about a local abortionist – no better than a serial killer – who’s been giving women quack pills and potions, followed by rudimentary operations that leave them to die of peritonitis, does he begin to wonder if Evie could have been pregnant when she died.

The novel peppers in lots of period slang and details about homeopathy, phrenology and early photography. Best of all, it has a surprise heroine: the Simpsons’ maid, Sarah Fisher, who keeps shaming Will with her practical medical know-how and ends up being something of a sidekick in his investigations. She wants to work as a druggist’s assistant, but the druggist insists that only a man can do the job. Dr. Simpson recognizes that the housemaid’s role is rather a waste of Sarah’s talents and expresses his hope that she’ll seek to be part of a widespread change for women.

The Way of All Flesh is sure to appeal to readers of Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White and Steven Price’s By Gaslight. It’s not quite as rewarding as the former, but the length and style make it significantly more engaging than the latter. It also serves as a good fictional companion to Lindsey Fitzharris’s The Butchering Art; for that reason, I wouldn’t be surprised to see it appear on next year’s Wellcome Book Prize longlist.

Victorian Edinburgh on the endpapers.

Favorite lines:

“That was Edinburgh for you: public decorum and private sin, city of a thousand secret selves.”

“‘Simpson likes to think of medicine as more than pure science,’ [Raven] countered. ‘There must also be empathy, concern, a human connection.’ ‘I suggest that both elements are required,’ offered Henry. ‘Scientific principles married to creativity. Science and art.’ If it is an art, it is at times a dark one, Raven thought, though he chose to keep this observation to himself.”

My rating:

The Way of All Flesh comes out today, August 30th, in the UK. It was published in the States by HarperCollins on the 28th. My thanks to Canongate for sending a free copy for review.