Three on a Theme: Trans Poetry for National Poetry Day

Today is National Poetry Day here in the UK. Alfie and I spent part of the chilly early morning reading from Pádraig Ó Tuama’s super Poetry Unbound, an anthology of 50 poems to which he’s devoted personal introductions and exploratory essays. He describes poetry as “like a flame: helping us find our way, keeping us warm.”

Poetry Unbound is also the name of his popular podcast; both were recommended to me by Sara Beth West, my fellow Shelf Awareness reviewer, in this interview we collaborated on back in April (National Poetry Month in the USA) about reading and reviewing poetry. I’ve been a keen reader of contemporary poetry for 15 years or so, but in the 3.5 years that I’ve been writing for Shelf I’ve really ramped up. Most months, I review a couple poetry collections for that site, and another one or more on here.

Two of my Shelf poetry reviews from the past 10 months highlight the trans experience; when I recently happened to read another collection by a trans woman, I decided to gather them together as a trio. All three pair the personal – a wrestling over identity – with the political, voicing protest at mistreatment.

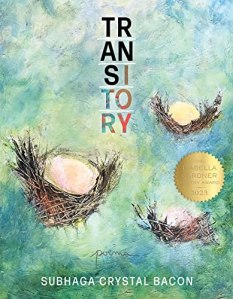

Transitory by Subhaga Crystal Bacon (2023)

In her Isabella Gardner Award-winning fourth collection, queer poet Subhaga Crystal Bacon commemorates the 46 trans and gender-nonconforming people murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2020—an “epidemic of violence” that coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The book arose from a workshop Bacon attended on writing “formal poems of social protest.” Among the forms employed here are acrostics and erasures performed on news articles—ironically appropriate for reversing trans erasure. She devotes one elegy to each hate-crime victim, titling it with their name and age as well as the location and date of the killing, and sifting through key details of their life and death. Often, trans people are misgendered or deadnamed in prison, by ambulance staff, or after death, so a crucial element of the tributes is remembering them all by chosen name and gender.

The statistics Bacon conveys are heartbreaking: “The average life expectancy of a Black trans woman is 35 years of age”; “Half of Black trans women spend time in jail”; “Trans people are anywhere/ between eleven and forty percent/ of the homeless population.” She also draws on her own experience of gender nonconformity: “A little butch./ A little femme.” She recalls of visiting drag bars in the 1980s: “We were all/ trying on gender.” And she vows: “No one can say a life is not right./ I have room for you in me.” Her poetic memorial is a valuable exercise in empathy.

Published by BOA Editions. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

I was interested to note that the below poets initially published under both female and male, new and dead names, as shown on the book covers. However, a look at social media makes it clear that the trans women are now going exclusively by female names.

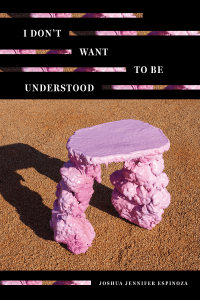

I Don’t Want to Be Understood by Jennifer Espinoza (2024)

In Espinoza’s undaunted fourth poetry collection, transgender identity allows for reinvention but also entails fear of physical and legislative violence.

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Two poems, both entitled “Airport Ritual,” articulate panic during a security pat-down on the way to visit family. In the first, a woman quells her apprehension by imagining a surreal outcome: her genitals expand infinitely, “tearing through her clothes and revealing an amorphous blob of cosmic energy.” In the second, the speaker chants the reassuring mantra, “I am not afraid.” “Makeup Ritual” vacillates between feminism and conformity; “I don’t even leave the house unless/ I’ve had time to build a world on my face/ and make myself palatable/ for public consumption.” Makeup is “your armor,” Espinoza writes in “You’re Going to Die Today,” as she describes the terror she feels toward the negative attention she receives when she walks her dog without wearing it. The murders of trans people lead the speaker to picture her own in “Game Animal.” Violence can be less literal and more insidious, but just as harmful, as in a reference to “the day the government announced another plan to strip a few/ more basic rights from trans people.”

Words build into stanzas, prose paragraphs, a zigzag line, or cross-hatching. Espinoza likens the body to a vessel for traumatic memories: “time is a body full of damage// that is constantly trying to forget.” Alliteration and repetition construct litanies of rejection but, ultimately, of hope: “When I call myself a woman I am praying.”

Published by Alice James Books. Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

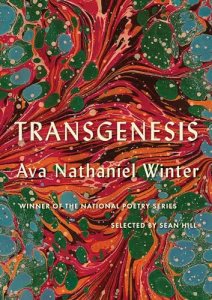

Transgenesis by Ava Winter (2024)

“The body is holy / and is made holy in its changing.”

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Winter’s debut full-length collection, selected by Sean Hill for the National Poetry Series, reckons with Jewishness as much as with gender identity. The second half of the title references any beginning, but specifically the scriptural account of creation and the lives of the matriarchs and patriarchs of the Abrahamic faiths. Poems are entitled “Torah Study” and “Midrash” (whence the above quote), and two extended sections, “Archived Light” and “Playing with the Jew,” reflect on Polish paternal family members’ arrival at Auschwitz and the dubious practice of selling Holocaust and Nazi memorabilia as antiques. Pharmaceuticals and fashion alike are tokens of transformation –

Let me greet now,

with warm embrace,

the small blue tablets

I place beneath my tongue each morning.

Oh estradiol,

daily reminder

of what our bodies

have always known:

the many forms of beauty that might be made

flesh by desire, by chance, by animal action.

(from “Transgenesis”)

The first time I wore a dress in public without a hint of irony—a Max Mara wrap adorned with Japanese lilies that framed my shoulders perfectly—I was still thin but also thickly bearded and men on the train whispered to me in a conspiratorial tone, as if they hoped the dress were a joke I might let them in on.

(from “WWII SS Wiking Division Badge, $55”)

– and faith grants affirmation that “there is beauty in such queer and fruitless bodies,” as the title poem insists, with reference to the saris (nonbinary person) acknowledged by the Talmudic rabbis. “Lament with Cello Accompaniment” provides an achingly gorgeous end to the collection:

I do not choose the sound of the song

In my mouth, the fading taste of what I still live through, but I choose this future, as I bury a name defined by grief, as I enter the silence where my voice will take shape.

Winter teaches English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. I’ll look out for more of her work.

Published by Milkweed Editions. (Read via Edelweiss)

More trans poetry I have read:

A Kingdom of Love & Eleanor Among the Saints by Rachel Mann

By nonbinary/gender-nonconforming poets, I have also read:

Surge by Jay Bernard

Like a Tree, Walking by Vahni Capildeo

Some Integrity by Padraig Regan

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Divisible by Itself and One by Kae Tempest

Binded by H Warren

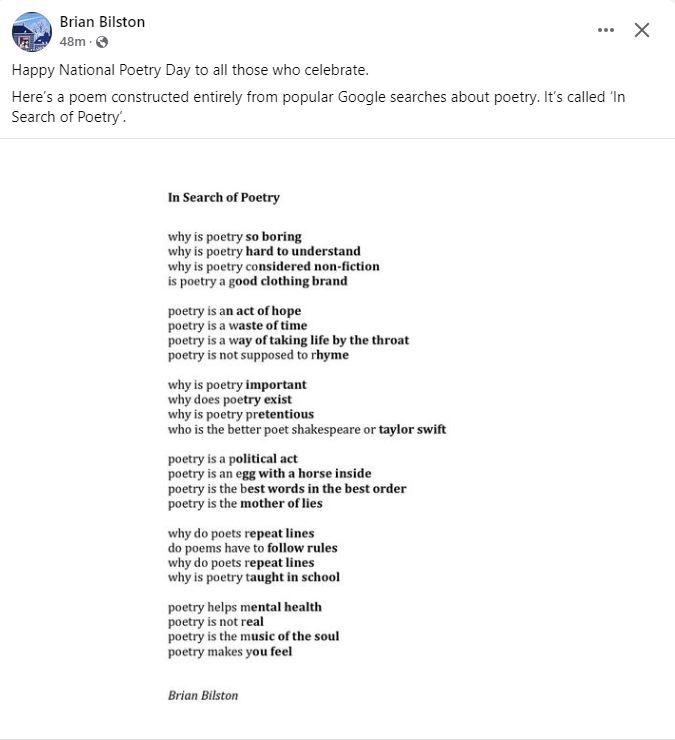

Extra goodies for National Poetry Day:

Follow Brian Bilston to add a bit of joy to your feed.

Editor Rosie Storey Hilton announces a poetry anthology Saraband are going to be releasing later this month, Green Verse: Poems for our Planet. I’ll hope to review it soon.

Two poems that have been taking the top of my head off recently (in Emily Dickinson’s phrasing), from Poetry Unbound (left) and Seamus Heaney’s Field Work: