Tag Archives: bullying

Autumn Reads: Don Freeman, Seamus Heaney, Jo Lindley, Alice Oseman

I keep a whole box full of future seasonal reads. Winter is the largest contingent because it includes Christmas, cold, snow and ice; followed by summer, which also covers heat, sun and so on. Every once in a while, I’ll come across a spring-related book. Autumn may be great for misty canal walks, vibrant leaves and variegated squashes, but it’s the hardest of the seasons to find books for. I’ve read all the obvious ones by now. Some of the below connections are more abstract but not too much of a stretch, I hope.

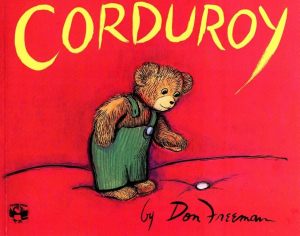

Corduroy by Don Freeman (1968)

Autumn is when I wear the most corduroy, sometimes (accidentally) head to toe.

I knew I’d read this as a child, but didn’t expect individual pages to feel so familiar. It must have been on frequent rotation in my house growing up. Corduroy the bear is among the toys on offer in a large department store. One morning Lisa, a little Black girl, picks him out, but her mother says no, they’ve spent too much already – and besides, the toy is damaged. He didn’t realize until her mother said: his green overall is missing a button. That night he rides the escalator to go look for the button, thinking he’ll never be loved until he’s complete. His adventure doesn’t turn out as planned, but Lisa hasn’t stopped thinking about him. Long before Toy Story, here was a sweet book about what toys get up to when we’re not around. And the repeated expressions of the bear’s meek wonderment – “This must be home,” “You must be a friend” – gave me the warm fuzzies. (Little Free Library)

I knew I’d read this as a child, but didn’t expect individual pages to feel so familiar. It must have been on frequent rotation in my house growing up. Corduroy the bear is among the toys on offer in a large department store. One morning Lisa, a little Black girl, picks him out, but her mother says no, they’ve spent too much already – and besides, the toy is damaged. He didn’t realize until her mother said: his green overall is missing a button. That night he rides the escalator to go look for the button, thinking he’ll never be loved until he’s complete. His adventure doesn’t turn out as planned, but Lisa hasn’t stopped thinking about him. Long before Toy Story, here was a sweet book about what toys get up to when we’re not around. And the repeated expressions of the bear’s meek wonderment – “This must be home,” “You must be a friend” – gave me the warm fuzzies. (Little Free Library)

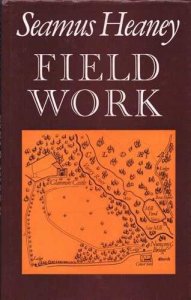

Field Work by Seamus Heaney (1979)

Harvest is a secondary theme in this poetry collection, which also has an overall melancholy tone that seems appropriate to the season of All Souls. Two poems are headed “In Memoriam” and another is titled “Elegy.” Even when they are not the stated topic, the Troubles rear up, as in the first section of “Triptych”: “Two young men with rifles on the hill, / Profane and bracing as their instruments. // Who’s sorry for our trouble?” The countryside can nevermore be an idyll when armoured cars and bombs could be anywhere. “The end of art is peace,” a late line from “The Harvest Bow,” may well be the poet’s motto (so long as “end” is interpreted as “goal”). There is a sequence of 10 sonnets and several poems devoted to animals. I experience Heaney’s poetry as linguistically fertile and formally rigorous; probably best heard out loud. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Marlborough)

Harvest is a secondary theme in this poetry collection, which also has an overall melancholy tone that seems appropriate to the season of All Souls. Two poems are headed “In Memoriam” and another is titled “Elegy.” Even when they are not the stated topic, the Troubles rear up, as in the first section of “Triptych”: “Two young men with rifles on the hill, / Profane and bracing as their instruments. // Who’s sorry for our trouble?” The countryside can nevermore be an idyll when armoured cars and bombs could be anywhere. “The end of art is peace,” a late line from “The Harvest Bow,” may well be the poet’s motto (so long as “end” is interpreted as “goal”). There is a sequence of 10 sonnets and several poems devoted to animals. I experience Heaney’s poetry as linguistically fertile and formally rigorous; probably best heard out loud. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Marlborough)

Autumnal passages I marked:

“We toe the line / between the tree in leaf and the bare tree.” (from “September Song”)

“the sunflower, dreaming umber” (from “Field Work”)

“A rowan like a lipsticked girl” (from “Song”)

“the sunset blaze / of straw on blackened stubble, a thatch-deep, freshening barbarous crimson burn” (from “Leavings”)

But none of those stood out to me as much as “Oysters,” the opening poem, which I photographed here. I’ve read and savoured every line of it five times now. It’s gold.

Hello Autumn by Jo Lindley (2023)

Depicted as elfin children, the seasons take turns wearing a single crown. Autumn is a timid soul worried about what might go wrong. But when one of the others is at risk, he rushes to help even if it might take him outside his comfort zone. By doing so, he realizes how much there is to enjoy in every season. This is part of a didactic series (Little Seasons/Best Friends with Big Feelings) about coping with anxiety. I’m surprised it wasn’t classified in the mostly-nonfiction “Family Matters” section of the children’s library, which includes books on feelings, illnesses, death, divorce, siblings, first experiences, etc. It was a little heavy-handed for me and I wasn’t sure why the characters had to be elves. (Public library)

Depicted as elfin children, the seasons take turns wearing a single crown. Autumn is a timid soul worried about what might go wrong. But when one of the others is at risk, he rushes to help even if it might take him outside his comfort zone. By doing so, he realizes how much there is to enjoy in every season. This is part of a didactic series (Little Seasons/Best Friends with Big Feelings) about coping with anxiety. I’m surprised it wasn’t classified in the mostly-nonfiction “Family Matters” section of the children’s library, which includes books on feelings, illnesses, death, divorce, siblings, first experiences, etc. It was a little heavy-handed for me and I wasn’t sure why the characters had to be elves. (Public library)

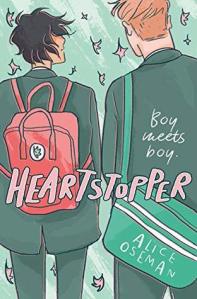

Heartstopper: Volume 1 by Alice Oseman (2019)

I’ve been rereading the series through the hardback reissue; I’m now on Volume 5 (and WHERE is Volume 6, huh?). I’ve included the first book because of the falling leaves motif on the cover, which fits the back-to-school vibe. (Public library)

I’ve been rereading the series through the hardback reissue; I’m now on Volume 5 (and WHERE is Volume 6, huh?). I’ve included the first book because of the falling leaves motif on the cover, which fits the back-to-school vibe. (Public library)

What I thought this time: Just as cute the second time around. All the looks, all the blushes, all the angst! I’d forgotten the details of how Nick and Charlie met and got together. Single best page: when Tori appears out of nowhere and says to Charlie of Nick, “I don’t think he’s straight.”

Original review: It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes.

#1970Club: Desperate Characters & I’m the King of the Castle

Simon and Karen’s classics reading weeks are always a great excuse to pick up some older books. I found on my shelves a chilly Brooklyn-set novella that has been praised to the skies by the likes of Jonathan Franzen, and then borrowed a short and unsettling novel about warring English schoolboys from the library.

Desperate Characters by Paula Fox

Other covers feature a cat, which is probably why this was on my radar. Don’t expect a cat lover’s book, though. The cat simply provides the opening incident. Sophie Bentwood is a forty-year-old underemployed translator; she doesn’t really need to work because her lawyer husband Otto keeps them in comfort. Feeding a feral cat, she is bitten savagely on the hand and over the next several days puts off seeking medical attention, wanting to stay in uncertainty rather than condemn herself to rounds of shots – and the cat to possible euthanasia. Both she and Otto live in this state of inertia. They were never able to have children but couldn’t take the step of adopting; Sophie had an affair but couldn’t leave Otto to commit elsewhere.

Other covers feature a cat, which is probably why this was on my radar. Don’t expect a cat lover’s book, though. The cat simply provides the opening incident. Sophie Bentwood is a forty-year-old underemployed translator; she doesn’t really need to work because her lawyer husband Otto keeps them in comfort. Feeding a feral cat, she is bitten savagely on the hand and over the next several days puts off seeking medical attention, wanting to stay in uncertainty rather than condemn herself to rounds of shots – and the cat to possible euthanasia. Both she and Otto live in this state of inertia. They were never able to have children but couldn’t take the step of adopting; Sophie had an affair but couldn’t leave Otto to commit elsewhere.

The cat bite seems to set off a chain of mishaps, culminating with the Bentwoods discovering that their house in the country has been vandalized. In the meantime, not a lot happens. The couple goes to a party and Sophie sneaks out for late-night drinks with her husband’s ex-partner, to whom she confides her affair. In Jonathan Franzen’s introduction, he compares to Bellow, Roth and Updike – but thinks Fox surpasses them all. The book explicitly references the Thoreau quote about people living lives of quiet desperation. I could sympathize with the midlife malaise depicted. As stagnant marriage stories go, this reminded me of what I’ve read by Richard Yates, just with a little less drinking. It would have made a good Literary Wives selection. In general, though, I can’t summon much enthusiasm. Given the cult classic status, I expected more. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill

I’m almost tempted to mark this as an R.I.P. read, because it’s very dark indeed. Like The Woman in Black, it takes place in an ominous English mansion and its environs. Other scenes take place in a creepy forest and at castle ruins, adding to the Gothic atmosphere. Edmund Hooper and his father move into Warings after his grandparents’ death. Soon his father makes an unwelcome announcement: he’s hired a housekeeper, Helena Kingshaw, who will be moving in with her son, Charles, who is the same age as Edmund. Hooper writes Kingshaw (as the boys are called throughout the book, probably to replicate how they were known at their boarding schools) a note: “I DIDN’T WANT YOU TO COME HERE.”

I’m almost tempted to mark this as an R.I.P. read, because it’s very dark indeed. Like The Woman in Black, it takes place in an ominous English mansion and its environs. Other scenes take place in a creepy forest and at castle ruins, adding to the Gothic atmosphere. Edmund Hooper and his father move into Warings after his grandparents’ death. Soon his father makes an unwelcome announcement: he’s hired a housekeeper, Helena Kingshaw, who will be moving in with her son, Charles, who is the same age as Edmund. Hooper writes Kingshaw (as the boys are called throughout the book, probably to replicate how they were known at their boarding schools) a note: “I DIDN’T WANT YOU TO COME HERE.”

That initial hostility erupts into psychological, and sometimes physical, abuse. Kingshaw quickly learns not to trust Hooper. “He thought, I mustn’t let Hooper know what I truly think, never, not about anything.” He tries running away to the woods but Hooper follows him; he makes friends with a local farm boy but it’s little comfort when he’ll soon be starting at Hooper’s school and it looks as if their lonely widowed parents might marry. The boys learn each other’s weaknesses and exploit them. At climactic moments, they have the opportunity to be gracious but retreat from every potential truce.

Heavy on dialogue and description, the book moves quickly with its claustrophobic scenes of nightmares come to life. Referring to the boys by surname makes them seem much older than 10 going on 11. Their antagonism is no child’s play – as the title ironically suggests – or harmless bullying. Is it evil? The reader feels for Kingshaw, the more passive one, yet what he does in revenge is nearly as bad. I was reminded somewhat of Harriet Said… by Beryl Bainbridge. It’s a deeply uncomfortable story, not least for how nature (pecking crows, cases of dead moths) is portrayed as equally menacing. (Public library)

Another 15 books from 1970 that I’ve read:

Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach (in the running for worst book I’ve ever read)

Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret by Judy Blume

Runaway Ralph by Beverly Cleary

Fifth Business by Robertson Davies

84, Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff

If Only They Could Talk by James Herriot

Ripley Under Ground by Patricia Highsmith

Crow by Ted Hughes

Moominvalley in November by Tove Jansson

Being There by Jerzy Kosiński

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

Sing Down the Moon by Scott O’Dell

Love Story by Erich Segal

The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

The Trumpet of the Swan by E.B. White

(Lots of children’s books there! Clearly they were considered modern classics during my 1980s childhood.)

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club and 1937 Club.

20 Books of Summer #11, Review Catch-up, and Wainwright Children’s Picks

Comparing my January–April reading totals with my May–July average, I see that my reading is down 57% over the last few months (at least in terms of number of books finished), and I can only blame the stress and time-consuming processes of moving house and DIY. I feel like I’ve slowed to a crawl through my various challenges, including my 20 Books.

With increasingly apocalyptic news filling my feeds, I find that I simultaneously a) want to retreat into books all the more and b) wonder what the point of all this compulsive reading is. For now, I’m taking as back-up Gretchen Rubin’s motto shared on National Book Lovers Day (“Reading is my tree house and my cubicle, my treadmill and my snow day” – what a perfect summary! It’s playtime, escape, mental exercise, indulgence but also, in some cases, work) and the premise of San Diego philosopher Nick Riggle’s upcoming This Beauty, which I’m reading for an early review: the purpose of life is to participate in and replicate beauty.

20 Books of Summer, #11

From the hedgerows: A collection of short stories on the wildlife, places and people of Newbury District by Lew Lewis (2008)

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

If you regularly read the Guardian Country Diary feature, you’ll find the format familiar. The general idea is to pick a natural phenomenon that’s seasonal or timely in some way, and write a short essay on it that incorporates context, personal observation, a political conscience and sometimes whimsical or nostalgic musing. Many pieces are about bird sightings; a few are about plants and insects; others celebrate the unique landscapes we have here, like heath and chalk downland. Some are quaint, like an introduction to “ticking” (birders’ list-keeping).

It was faintly depressing to see that we’ve been noting these habitat and species losses and their causes (generally, intensified agriculture) for over 30 years, and haven’t done enough to reverse them. But there are some good news stories, too, like “Return of the Red Kite,” one of our flagship species. This is basically self-published and could have done with some extra proofreading, but the black-and-white illustrations, most by Richard Allen, are charming. I was so pleased to find this on my library reshelving trolley one day. It’s an important artefact of a nature-lover’s heritage. There should be a follow-up volume or two! (Public library)

Review Book Catch-up

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022)

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022)

I discovered Caroline Bird early last year through In These Days of Prohibition and her latest collection, The Air Year, was one of my favourite reads of 2021. Part of the joy of working my way through this chronological volume was finding the traces of Bird’s later surrealism. Her first collection, Looking through Letterboxes, was written when she was just 14 and published when she was 16, but you’d never guess that from reading these poems of family, fairy tales and unspecified longing. I particularly liked the first stanza of “Passing the Time”:

Thirty paperclip statues on every table in the house

and things are slightly boring without you.

I’ve knitted a multi-coloured jacket for every woodlouse

in the park. But what can you do?

Trouble Came to the Turnip has some cheeky and randy fare, with the title poem offering a beleaguered couple various dubious means of escape. Watering Can pits monogamy and marriage against divorce and the death of love, via some twisted myths and fairy tales (e.g., Narcissus and Red Riding Hood). “Last Tuesday” is a stand-out. The Hat-Stand Union has more of what I most associate with Bird’s verse: dreams and the surreal. “How the Wild Horse Stopped Me” was a favourite. Mostly, I’m glad I own this so I can have access to the material from her two latest collections, but it was also fun to encounter her earlier style. In an afterword, she writes: “I chose poetry because it let me hide and, once hidden, I could be brave, roll my heart in sequins and chuck it out, glittering, into the street.”

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Getting through It: My Year of Cancer during Covid by Helen Epstein (2022)

Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with Covid chronicles, this was always going to appeal to me. Epstein, an arts journalist and nonfiction author born in Prague and based in Massachusetts, was diagnosed with endometrial cancer in June 2020. She documents the next year or so in a matter-of-fact diary format, never shying away from the details of symptoms, medical procedures and side effects. Her husband Patrick’s e-mail updates sent out to friends and family, and occasional medical reports, fill in the parts she was less clear on due to fatigue and brain fog – including two small strokes she suffered. Surgery was followed by chemo and then the fraught decision of whether to decline brachytherapy (internal radiation). And, of course, all this was happening at a time when people were less able to see loved ones and rely on their regular diversions. The apt cover conjures up the outdoor chaise longue where Epstein would hold court and receive visitors.

Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with Covid chronicles, this was always going to appeal to me. Epstein, an arts journalist and nonfiction author born in Prague and based in Massachusetts, was diagnosed with endometrial cancer in June 2020. She documents the next year or so in a matter-of-fact diary format, never shying away from the details of symptoms, medical procedures and side effects. Her husband Patrick’s e-mail updates sent out to friends and family, and occasional medical reports, fill in the parts she was less clear on due to fatigue and brain fog – including two small strokes she suffered. Surgery was followed by chemo and then the fraught decision of whether to decline brachytherapy (internal radiation). And, of course, all this was happening at a time when people were less able to see loved ones and rely on their regular diversions. The apt cover conjures up the outdoor chaise longue where Epstein would hold court and receive visitors.

In my mind, cancer patients fall into two camps: those who want to read everything they can about their illness so they know what to expect, and those who avoid thinking about it at all costs. For those in the former group, a no-nonsense book like this will be invaluable. I particularly appreciated Epstein’s attention to her husband’s experience, which she had to dig a little deeper to understand, and her realization that having female cancer brought back memories of childhood sexual molestation. She is also candid about how other people’s emotional demands (e.g., recounting a family member’s illness, or expecting effusive gratitude for small thoughtful acts) weighed on her. A forthright Everywoman’s narrative.

With thanks to the author for the free e-copy for review. Full disclosure: We are acquaintances through a Facebook group for book reviewers.

Wainwright Children’s Prize shortlist

I’ve now read 4 of 7 books on the Wainwright Prize’s Children’s Nature and Conservation Writing shortlist. I’m unlikely to have a chance to read the other three before the winner is announced unless my library system acquires them quickly. Any of the ones I’ve read would make a deserving winner, but the two I review below really grabbed me by the heartstrings and I would be particularly delighted to see one or the other take this inaugural award.

One World: 24 Hours on Planet Earth by Nicola Davies, illus. Jenni Desmond (2022)

It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

A lot of research went into ensuring accuracy, and the environmentalist message is clear but not overstated. Fantastic! (Public library)

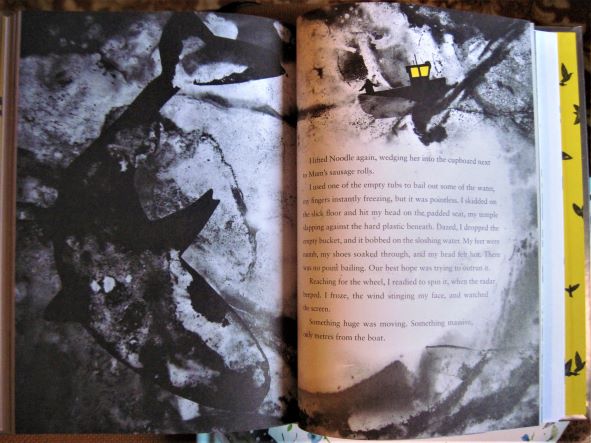

Julia and the Shark by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, illus. Tom de Freston (2021)

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

Hargrave treats the shark as both a real creature and a metaphor for all that lurks – all that we fear and don’t understand. It and murmurations of starlings are visual motifs throughout the book, which has a yellow and black colour scheme. Like One World, it’s as beautifully illustrated as it is profound in its messages. Julia is no annoyingly precocious child narrator, just a believable one who shows us her struggling family and the love and magic that get them through. I could see this becoming a modern children’s classic. (Public library)