Tag Archives: Counterpoint Press

January Releases: Greathead, Kauffman, Mills & Watts (#ReadIndies)

I feel out of practice writing reviews after the endless period of sluggish and slightly lackluster reading that was January. Here we are at the start of Kaggsy and Lizzy Siddal’s Reading Independent Publishers Month challenge and I’m happy to make this my first tie-in post as these four books all happen to be from independent publishers. The first two are American novels (that could arguably be called linked short story collections) very much in my wheelhouse for their focus on dysfunctional families and disappointing characters. I also have a group biography aiming to illuminate bisexuality, and a poetry collection about girlhood/womanhood and nature.

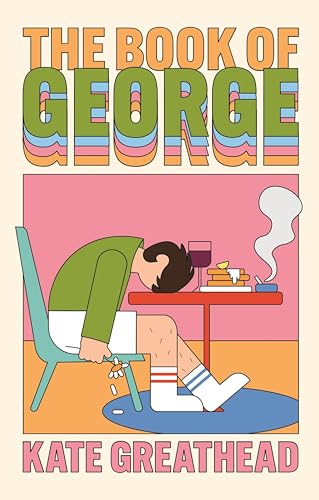

The Book of George by Kate Greathead

The marketing for this novel courts relatability: you probably know a George – you might have dated one (women read the most litfic). Each chapter dates to a different period in George’s life, adolescence to late thirties. From the fact that 9/11 happened when he was a college freshman, I know he’s my exact contemporary, and I could indeed see bits of myself in this Everyman schmuck: indecisive, lazy, underachieving, privileged but never living up to his own or others’ expectations. Life keeps happening around him, but you wonder if he’ll ever make something happen for himself. Two gags are revealing: In college he is known for his impression of a clinically depressed penis going through airport security, and later he has 15 minutes of fame for appearing in a hidden-camera Super Bowl commercial. He’s been writing fiction for years – first a Stoner rip-off, then a Kerouac homage – but by the time he gets a short story collection together, it’s the height of #MeToo and he’s missed his moment to publish. Meanwhile, his cohort is doing great things, winning awards for documentaries (his pal Jeremiah) or becoming pro bono lawyers (his longsuffering girlfriend Jenny).

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review. (Published in the USA by Henry Holt and Co. in 2024.)

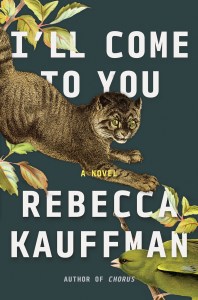

I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman

Is 30 years long enough ago to count as historical fiction? In any case, this takes us through the whole of 1995, proceeding month by month and rotating through the close third-person perspectives of the members of one extended family as they navigate illnesses, break-ups and fraught parenting journeys. Corinne and Paul are trying to get pregnant; Paul’s mother, Ellen (again!), is still smarting from her husband leaving with no explanation; Corinne’s father, Bruce, has dementia but his wife, Janet, is doing her best to keep his cognitive deficiencies from the rest of the family. Son Rob is bitter about his ex-wife moving on so quickly, but both he and Ellen will have new romantic prospects before the end.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

With thanks to Counterpoint (USA) for the advanced e-copy for review.

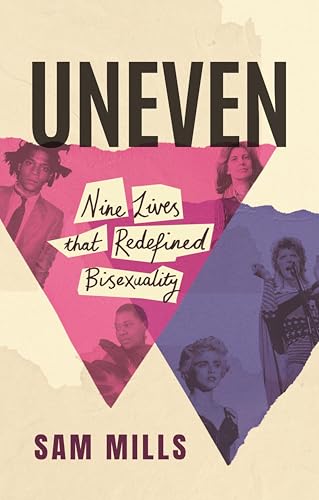

Uneven: Nine Lives that Redefined Bisexuality by Sam Mills

Back in 2022 I reviewed Julia Shaw’s Bi: The hidden culture, history and science of bisexuality, which took a social sciences approach. By contrast, this is a group biography of nine bisexuals – make that 10, as there are plenty of short memoir-ish passages from Mills, too. Oscar Wilde, Colette, Marlene Dietrich, Anaïs Nin, Susan Sontag: more or less familiar names, though not all of them are necessarily known for their sexuality. The chapters deliver standard potted biographies of the individuals’ work and relationships, probably containing little that couldn’t be found elsewhere in recent scholarship and not really living up to the revolutionary promise of the subtitle. However, it was worthwhile for Mills to recover Wilde as a bisexual rather than a closeted homosexual. A final trilogy of chapters comes more up to date with David Bowie, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Madonna. The closer to the present day, the more satisfying connections there are between figures. For instance, Madonna looked to both Dietrich and Bowie as role models and fashion icons, and she and Basquiat were lovers.

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

The 1890s to 1980s window allows for a record of changing mores yet means that the book seems rather dated. Were it written by an author of a later generation (Mills, who I knew for The Fragments of My Father, is around 50), the point of view and terminology would likely be quite different. Also, including a section on Bessie Smith within a chapter mostly on Colette felt tokenistic. (Though later considering Basquiat separately does add a BIPOC view.) Ultimately, though, my problem with Uneven was that I don’t want to know about behaviour – which is all that a biography can usually document – so much as the internal, soul stuff. Even from Mills, whose accounts of her long-term relationships and flings (including, yes, a threesome) can be titillating but not very enlightening, I didn’t get a sense of what it feels like. So neither the Shaw nor the Mills gave me precisely what I was looking for, which means that the perfect book on bisexuality either doesn’t exist or is out there but I haven’t found it yet. Any suggestions?

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

The Face in the Well by Rebecca Watts

I’ve also read Watts’ The Met Office Advises Caution and Red Gloves; this is her third collection. The Suffolk and Cambridgeshire scenery of her early and adult lives weaves all through, sometimes as an idyll that blurs the lines between humans and nature (“Private No Access”) but other times provoking anxiety about common or gendered dangers, as in the title poem or “The Old Mill” (“What happened there, / down by the old mill, / they never tell. // Something about / a man and a girl / is the most you’ll hear.”). “Woman Seeks” is a tongue-in-cheek advert for the perfect man. Animals – a dolphin, a shark, rodents, a wandering albatross, a robin – recur, as do women poets, especially Emily Brontë, and Victorian death culture (“Victoriana” and “Baroque”). Adulthood brings routine whereas childhood stands out for minor miracles, such as a free soda from a vending machine.

I’ve also read Watts’ The Met Office Advises Caution and Red Gloves; this is her third collection. The Suffolk and Cambridgeshire scenery of her early and adult lives weaves all through, sometimes as an idyll that blurs the lines between humans and nature (“Private No Access”) but other times provoking anxiety about common or gendered dangers, as in the title poem or “The Old Mill” (“What happened there, / down by the old mill, / they never tell. // Something about / a man and a girl / is the most you’ll hear.”). “Woman Seeks” is a tongue-in-cheek advert for the perfect man. Animals – a dolphin, a shark, rodents, a wandering albatross, a robin – recur, as do women poets, especially Emily Brontë, and Victorian death culture (“Victoriana” and “Baroque”). Adulthood brings routine whereas childhood stands out for minor miracles, such as a free soda from a vending machine.

The format and tone vary a lot, so the book is more of a grab bag than a cohesive statement. I noted slant rhymes and alliteration, always a favourite technique of mine. I especially liked “Entropy,” about finding a slice of cake in the freezer labeled by someone who is now dead (“Nothing ever // really dies: all the pieces of you / persist, riven and reconfigured / in infinite unknowable ways”) and “Personal Effects,” about the artefacts from her childhood that her mother guards under the bed (“twists of my hair, my teeth, / my bracelet from the hospital.”).

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Which of these appeal to you? What indie publishers have you been reading from recently?

Nonfiction Review Books Roundup: Hay, Hope et al., Lee, Long, McLaren, Zuckerman

I’m continuing with the Nonfiction November focus by catching up on six nonfiction review books I’ve been sent over the last half a year. We’ve got a record of elderly parents’ decline, letters and poems written about the climate crisis, a family memoir set between Taiwan and Canada, a widow’s mushroom-hunting quest, a work of ecotheology that reflects on travels in the Galápagos Islands, and a defense of an entirely secular basis for morality. You can’t say I don’t read a variety, even within nonfiction! See if one or more of these tempts you.

All Things Consoled: A Daughter’s Memoir by Elizabeth Hay

Gordon and Jean Hay stumbled into their early nineties in an Ottawa retirement home starting in 2009. Elizabeth Hay is one of four children, but caregiving fell to her for one reason and another, and it was a fraught task because of her parents’ prickly personalities: Jean was critical and thrifty to the point of absurdity, spooning thick mold off apple sauce before serving it and needling Elizabeth for dumping perfectly good chicken juice a year before; Gordon had a terrible temper and a history of corporal punishment of his children and of his students when he was a school principal. Jean’s knee surgery and subsequent infection finally put paid to their independence; her mind was never the same and she could no longer paint.

Gordon and Jean Hay stumbled into their early nineties in an Ottawa retirement home starting in 2009. Elizabeth Hay is one of four children, but caregiving fell to her for one reason and another, and it was a fraught task because of her parents’ prickly personalities: Jean was critical and thrifty to the point of absurdity, spooning thick mold off apple sauce before serving it and needling Elizabeth for dumping perfectly good chicken juice a year before; Gordon had a terrible temper and a history of corporal punishment of his children and of his students when he was a school principal. Jean’s knee surgery and subsequent infection finally put paid to their independence; her mind was never the same and she could no longer paint.

There are many harsh moments in this memoir, but almost as many wry ones, with Hay picking just the right anecdotes to illustrate her parents’ behavior and the shifting family dynamic. She never looks away, no matter how hard it all gets. Her father’s rage against the dying of the light contrasts with her mother’s fade into confusion – lightened by the surprisingly poetic turns of phrase she came out with despite her dementia and aphasia. The title phrase, for instance, was her attempt at “all things considered.” I would wholeheartedly recommend this to readers of Hay’s novels, but anyone can appreciate the picture of complicated love and grief. (See also Susan’s review.)

With thanks to MacLehose Press for the free copy for review.

Letters to the Earth: Writing to a Planet in Crisis, edited by Anna Hope et al.

Culture Declares Emergency launched in April to bring the arts into the conversation about the climate emergency. Letters to the Earth compiles 100 short pieces by known and unknown names alike. Alongside published authors, songwriters, professors and politicians are lots of ordinary folk, including children as young as seven. The brief was broad: to write a letter in response to environmental crisis, whether to or from the Earth, to future generations (there are wrenching pieces written to children: “What can I say, now that it’s too late? … that I’m sorry, that I tried,” writes Stuart Capstick), to the government or to other species.

Culture Declares Emergency launched in April to bring the arts into the conversation about the climate emergency. Letters to the Earth compiles 100 short pieces by known and unknown names alike. Alongside published authors, songwriters, professors and politicians are lots of ordinary folk, including children as young as seven. The brief was broad: to write a letter in response to environmental crisis, whether to or from the Earth, to future generations (there are wrenching pieces written to children: “What can I say, now that it’s too late? … that I’m sorry, that I tried,” writes Stuart Capstick), to the government or to other species.

There are certainly relatable emotions here, especially the feeling of helplessness. “We take the train, go vegan, refuse plastic, buy less and less. But that is tiny. We are tiny,” novelist Jo Baker writes. I loved retired bishop Richard Holloway’s wry letter calling the author of Genesis to account for unhelpful language of dominion, Rob Cowen’s poem to a starling, and Anna Hope’s essay about parenting in a time of uncertainty. Unfortunately, much of the rest is twee or haranguing, e.g. “Forest fires are scorching INNOCENT wildlife. Plastic is strangling INNOCENT turtles and dolphins,” a 12-year-old writes. This was put together in a matter of months, and it shows. There is not enough tonal variety, a lot of overwriting has crept through, and errors, especially in the kids’ work, remain uncorrected. Perhaps six to 10 pieces stood out to me overall. I’d recommend the Extinction Rebellion handbook instead.

With thanks to Alison Menzies / William Collins for the free copy for review.

Two Trees Make a Forest: On Memory, Migration and Taiwan by Jessica J. Lee

I loved Turning, Lee’s 2017 memoir about swimming in one of Berlin’s lakes per week for a year, so I jumped at the chance to read her follow-up, which delves into her maternal line’s history in Taiwan. She travels to Taipei for three months to brush up on her Chinese, write and hike. Interspersed with the lush descriptions of her walks are reflections on Taiwan’s history and on the hidden aspects of her grandfather Gong’s past that only came to light after Lee’s grandmother, Po, died and she and her mother discovered an autobiographical letter he’d written before he drifted into dementia. Nature, language, history and memory flow together in a delicate blend of genres – “I moved from the human timescale of my family’s story through green and unfurling dendrological time,” she writes.

I loved Turning, Lee’s 2017 memoir about swimming in one of Berlin’s lakes per week for a year, so I jumped at the chance to read her follow-up, which delves into her maternal line’s history in Taiwan. She travels to Taipei for three months to brush up on her Chinese, write and hike. Interspersed with the lush descriptions of her walks are reflections on Taiwan’s history and on the hidden aspects of her grandfather Gong’s past that only came to light after Lee’s grandmother, Po, died and she and her mother discovered an autobiographical letter he’d written before he drifted into dementia. Nature, language, history and memory flow together in a delicate blend of genres – “I moved from the human timescale of my family’s story through green and unfurling dendrological time,” she writes.

This has got to be one of the most striking title and cover combinations of the year. Along with Chinese characters, the book includes some looping text and Nico Taylor’s maps and illustrations of Taiwanese flora and fauna. While you will likely get more out of this if you have a particular interest in Asian history, languages and culture, it’s impressive how Lee brings the different strands of her story together to form a hybrid nature memoir that I hope will be recognized by next year’s Wainwright Prize and Young Writer of the Year Award shortlists. She’d also be a perfect New Networks for Nature speaker.

With thanks to Virago for the free copy for review.

The Way through the Woods: Of Mushrooms and Mourning by Long Lit Woon

[Trans. from the Norwegian by Barbara J. Haveland]

[Trans. from the Norwegian by Barbara J. Haveland]

I couldn’t resist the sound of a bereavement memoir crossed with a mushroom hunting guide. When Long met her husband, Eiolf Olsen, she was an 18-year-old Malaysian exchange student in Stavanger, Norway. Meeting Eiolf changed the whole course of her life, keeping her in Europe for good; decades later, her life changed forever once again when Eiolf dropped dead at work one morning. “If anyone had told me that mushrooms would be my lifeline, the thing that would help me back onto my feet and quite literally back onto life’s track, I would have rolled my eyes. What had mushrooms to do with mourning?” she writes.

The answer to that rhetorical question is nothing much, at least not inherently, so this ends up becoming a book of two parts, with the bereavement strand (printed in green and in a different font – green is for grief? I suppose) engaging me much more than the mushroom-hunting one, which takes her to Central Park and the annual Telluride, Colorado mushroom festival as well as to Norway’s woods again and again – “In Norway, outdoor life is tantamount to a religion.” But the quest for wonder and for meaning is a universal one. In addition, if you’re a mushroom fan you’ll find gathering advice, tasting notes, and even recipes. I fancy trying the “mushroom bacon” made out of oven-dried shiitakes.

The answer to that rhetorical question is nothing much, at least not inherently, so this ends up becoming a book of two parts, with the bereavement strand (printed in green and in a different font – green is for grief? I suppose) engaging me much more than the mushroom-hunting one, which takes her to Central Park and the annual Telluride, Colorado mushroom festival as well as to Norway’s woods again and again – “In Norway, outdoor life is tantamount to a religion.” But the quest for wonder and for meaning is a universal one. In addition, if you’re a mushroom fan you’ll find gathering advice, tasting notes, and even recipes. I fancy trying the “mushroom bacon” made out of oven-dried shiitakes.

With thanks to Scribe for the free copy for review.

God Unbound: Theology in the Wild by Brian McLaren

McLaren was commissioned to launch a series that was part travel guide, part spiritual memoir and part theological reflection. Specifically, he was asked to write about the Galápagos Islands because he’d been before and they were important to him. He joins a six-day eco-cruise that tours around the island chain off Ecuador, with little to do except observe the birds, tortoises and iguanas, and swim with fish and sea turtles. For him this is a peaceful, even sacred place that reminds him of the beauty that still exists in the world despite so much human desecration. Although he avoids using his phone except to quickly check in with his wife, modernity encroaches unhelpfully through a potential disaster with his laptop.

McLaren was commissioned to launch a series that was part travel guide, part spiritual memoir and part theological reflection. Specifically, he was asked to write about the Galápagos Islands because he’d been before and they were important to him. He joins a six-day eco-cruise that tours around the island chain off Ecuador, with little to do except observe the birds, tortoises and iguanas, and swim with fish and sea turtles. For him this is a peaceful, even sacred place that reminds him of the beauty that still exists in the world despite so much human desecration. Although he avoids using his phone except to quickly check in with his wife, modernity encroaches unhelpfully through a potential disaster with his laptop.

I was surprised to see that McLaren leaves the Galápagos at the midpoint – whatever could fill the rest of the book, I wondered? He starts by reassessing Darwin, so often painted as a villain by Evangelical Christianity but actually a model of close, loving attention to nature. He also recalls how some of his most intense spiritual experiences have arisen from time in nature. McLaren’s books have been pivotal to my spiritual journey as we’ve both gradually become more liberal and environmentalist. His definition of God might horrify traditionalists, but holds appeal for me: “a centering singularity whose gravity holds me in insistent orbit, pulling me deeper into mystery, pondering who I am and what my life means.” This is an unusual but gently entrancing book full of photos and quotes from other thinkers including John Muir, Pope Francis and Richard Rohr. It’s an ideal introduction to ecotheology.

With thanks to Canterbury Press for the free copy for review.

What It Means to Be Moral: Why Religion Is Not Necessary for Living an Ethical Life by Phil Zuckerman

From one end of the spectrum (progressive Christianity) to the other (atheism). Here’s a different perspective from a sociology professor at California’s Pitzer College. Zuckerman’s central argument is that humanism and free choice can fuel ethical behavior; since there’s no proof of God’s existence and theists have such a wide range of beliefs, it’s absurd to slap a “because God says so” label on our subjective judgments. Morals maintain the small communities our primate ancestors evolved into, with specific views (such as on homosexuality) a result of our socialization. Alas, the in-group/out-group thinking from our evolutionary heritage is what can lead to genocide. Instead of thinking in terms of ‘evil’, though, Zuckerman prefers Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen’s term, “empathy erosion.”

From one end of the spectrum (progressive Christianity) to the other (atheism). Here’s a different perspective from a sociology professor at California’s Pitzer College. Zuckerman’s central argument is that humanism and free choice can fuel ethical behavior; since there’s no proof of God’s existence and theists have such a wide range of beliefs, it’s absurd to slap a “because God says so” label on our subjective judgments. Morals maintain the small communities our primate ancestors evolved into, with specific views (such as on homosexuality) a result of our socialization. Alas, the in-group/out-group thinking from our evolutionary heritage is what can lead to genocide. Instead of thinking in terms of ‘evil’, though, Zuckerman prefers Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen’s term, “empathy erosion.”

To tackle violent crime, Zuckerman contends, we need a more equal society, with the Scandinavian countries a model of how to achieve that through higher taxes, social services and the rehabilitation of prisoners. He uses a lot of relatable examples from history and from his own experience, as well as theoretical situations, to think through practical morality. I found his indictment of American Christianity accurate – how does it make sense for people who say they follow the way of Jesus to fight against equality, tolerance and scientific advances and instead advocate guns, the death penalty and Trump? Well, indeed.

It might seem odd for me to recommend this alongside the McLaren, but there is much to be gained from both viewpoints. Zuckerman’s work overlaps a fair bit with another I’ve read on the topic, Richard Holloway’s Godless Morality – even a bishop agrees we needn’t take our societal ethics straight from the Bible! I can’t go along fully with Zuckerman because I think progressive religion has been and can continue to be a force for good, but I would agree that atheists can be just as moral as people of faith – and often more so.

With thanks to Counterpoint Press for sending a proof copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Late in the Day by Tessa Hadley & Improvement by Joan Silber

Late in the Day by Tessa Hadley (2019)

Two London couples: Christine and Alex, and Lydia and Zachary. They’ve known each other for decades, and their affiliations have changed in major, even ironic ways. It was Lydia who was initially infatuated with Alex when he taught both her and Christine, and Christine and Zachary who dated for a time. But this is how things ultimately fell out, each marriage resulting in one daughter. Christine with Alex; Lydia with Zachary.

The cover image is Raja (1925) by Felice Casorati.

Except now Zachary is dead. The phone call comes in the novel’s very first sentence. How Lydia and her friends – not to mention her daughter, Grace, who’s studying art in Glasgow – will cope with the loss, and rearrange what was once such a comfortable quadrilateral, is the ostensible subject of the rest of the book. There’s a funeral to plan and a future for Lydia to construct. But the problem, for me, is that every other chapter hosts a seemingly endless flashback to the couples’ backstory. Apart from an odd, titillating moment when the four nearly let down their guard together, these sections don’t reveal an awful lot.

This is my sixth book by Tessa Hadley. Her eye is always sharp on how families work, how relationships fall apart, and how memories form and linger as we age. She’s also a master of third-person omniscience, moving effortlessly between characters’ perspectives. The writing here is exquisite; there’s no question about that. I especially love the descriptive passages, full of so much sensual detail that you can imagine yourself right into a scene:

A breeze fanned the newspaper on the table, the smells of a city summer were wafted through the open window: tar and car exhaust, the bitter-green of the flowering privet hedge. Police horses went past in the broad street, their hooves clip-clopping conversationally alongside the voices of the women who rode them; the stables were nearby.

Her perception was a skin stretched taut, prickling with response to each change in the light outside as it ran through the drama of its sunset performance at the end of the street, in a mass of gilded pink cloud. When eventually the copper beech was only a silhouette cut out against the blue of the last light, Christine pulled down the blinds, put on all the lamps, turned her awareness inwards.

Despite the fine prose, I found the past strand of this novel tedious. If you’re new to Hadley, I’d recommend starting with Clever Girl and/or Bad Dreams and Other Stories.

Late in the Day was published in the UK by Jonathan Cape on February 14th, and in the USA by Harper on January 15th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Improvement by Joan Silber (2017)

I’ve been thinking a lot about linked short story collections, having written a brief article about them for BookBrowse to accompany my review of Carrianne Leung’s That Time I Loved You (those who contributed ideas on Twitter, thank you!). I find them easier to read than the average short story volume because there are fewer characters and settings to keep track of, and you get the fun of tracing unexpected connections between characters. Improvement didn’t quite work for me in that way, mostly because you can tell that it started as one short story, “About My Aunt”: now the untitled first chapter, it is, as you might guess, a solid stand-alone narrative about Reyna and her aunt Kiki. It was originally published in Tin House and collected in The Best American Short Stories 2015.

I was most interested in Kiki, a terrific character with a completely unsuitable name. Her marriage to a Turk failed – but hey, at least she got a great rug out of it, as well as the fun but temporary challenge of third-world life. (“For a hardheaded person, she had let herself be flung about by the winds of love, and she wasn’t sorry either.”) Back in New York City she directs a house-cleaning agency and babysits for Reyna’s four-year-old son, Oliver. Tattooed Reyna’s African-American boyfriend, Boyd, is in prison for three months for selling pot; when he gets out he comes up with the bright idea of smuggling cigarettes between Virginia and New York to profit from the tax difference. He asks Reyna to make one of the pick-ups, but she chickens out at the last minute. Boyd’s friend Claude drives instead, and is killed instantly in a crash.

I was most interested in Kiki, a terrific character with a completely unsuitable name. Her marriage to a Turk failed – but hey, at least she got a great rug out of it, as well as the fun but temporary challenge of third-world life. (“For a hardheaded person, she had let herself be flung about by the winds of love, and she wasn’t sorry either.”) Back in New York City she directs a house-cleaning agency and babysits for Reyna’s four-year-old son, Oliver. Tattooed Reyna’s African-American boyfriend, Boyd, is in prison for three months for selling pot; when he gets out he comes up with the bright idea of smuggling cigarettes between Virginia and New York to profit from the tax difference. He asks Reyna to make one of the pick-ups, but she chickens out at the last minute. Boyd’s friend Claude drives instead, and is killed instantly in a crash.

Part II reaches into the lives of some of the minor characters on the fringes: Claude; Teddy, the truck driver who was the other party in the car accident; Osman, Kiki’s ex-husband; a trio of Germans who passed through their Turkish town in the summer of 1977 with smuggled antiquities in their possession; and so on. For me, these narratives were too diffuse and didn’t hang together as a novel. I had hoped to enjoy this more since it won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction and Silber is one of those writer’s writers you always hear about but never get to read. I found her voice similar to Anne Tyler’s or perhaps Julia Glass’s, but I’m not sure I’d try another book by her.

Improvement was published by Allen & Unwin on February 7th. It came out in the USA from Counterpoint Press in 2017. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Bottom line for both:

Subtle, sophisticated but underwhelming.

Magdalena Mountain by Robert Michael Pyle

“Wasn’t it Nabokov who said ‘It is astounding how little the ordinary person notices butterflies?’”

Butterflies, monks, students and teachers, prophets and saints: such is the cast of naturalist Robert Michael Pyle’s unusual and rewarding debut novel, Magdalena Mountain. It’s a golden autumn in the early 1970s as James Mead leaves Albuquerque on a Greyhound bus to travel to New Haven, Connecticut, where he will undertake a PhD in biology at Yale. He squats in a lab on campus to save money and, after some tension with his thesis advisor, decides to keep his head down, feeding the department’s giant cave roaches and becoming engrossed in the field journals written by one October Carson in 1969 during his travels out West.

Butterflies, monks, students and teachers, prophets and saints: such is the cast of naturalist Robert Michael Pyle’s unusual and rewarding debut novel, Magdalena Mountain. It’s a golden autumn in the early 1970s as James Mead leaves Albuquerque on a Greyhound bus to travel to New Haven, Connecticut, where he will undertake a PhD in biology at Yale. He squats in a lab on campus to save money and, after some tension with his thesis advisor, decides to keep his head down, feeding the department’s giant cave roaches and becoming engrossed in the field journals written by one October Carson in 1969 during his travels out West.

Pyle presents nature as both beatific and harsh, a continuity of life that human events – like a car going over a cliff in the first chapter – barely disrupt. Occasional chapters check in on the woman who was in the car crash, Mary Glanville. Now suffering from amnesia, she believes she’s a famous figure from history. One day she escapes from her nursing home and hitchhikes into the Colorado mountains. In her weakened state she’s taken in by Attalus and Oberon, monks at a deconsecrated monastery devoted to the god Pan and the creeds of nature writers like John Burroughs, Aldo Leopold and John Muir. Attalus, a compassionless misogynist, vehemently protests Mary’s presence in their community, but Oberon soon falls in love with her.

When James, disobeying his supervisor, lights out for Colorado for a summer of research at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, the stage is set for these major characters to collide on Magdalena Mountain, home to the distinctive, all-black Magdalena Alpine butterfly (Erebia magdalena). “Flight may appear weak, but adults are able to sail up and over huge boulders with the greatest of ease, eluding humans who desire a closer look. Flies in summer,” reads the description in my (Kaufman) field guide to North American butterflies. Intermittent segments of pure nature writing about Erebia’s life cycle – seven short chapters in total – establish the seasons and encourage a long view of local history, but somewhat slow down the novel’s tempo.

Pyle successfully pulls in so many different themes: academic infighting and the impulses of scientific researchers versus amateur collectors; environmentalism, especially through the threats that infestations, pesticides and off-road vehicles pose to the mountain landscape; activism, by way of the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons protests; and even sacred femininity and the myths surrounding Mary Magdalene. Mary Glanville’s name is a nice nod to history – Elinor Glanville was a seventeenth-century English collector who gave her name to the Glanville Fritillary – while Vladimir Nabokov, who was a keen lepidopterist as well as an academic and author, is mentioned several times for his real-life connections to the area.

(A selection of my butterfly-themed books, read and unread, in the pile at the left.)

The quirky set of hangers-on at the monastery reminded me of an Iris Murdoch setup (thinking mostly of The Bell), while the passion for science and activism brought to mind two other excellent environmentally minded novels published this year, The Overstory and Unsheltered. Indeed, Mary preaches at one point, “Seek your shelter in nature … In love lies the only real shelter there is.” If you’re interested in the Powers and/or Kingsolver, I would commend Pyle’s book to you as well: it’s offbeat, dreamy yet fervent, with intriguing characters and elegant nature-infused language. One of my favorite descriptive scraps, so simple but so apt, was “a peeled peach of a moon.” I’m grateful to have had a chance to read this, and I will be seeking out Pyle’s nature writing, too.

My rating:

Magdalena Mountain was published in August 2018. My thanks to the good folk of Counterpoint Press (based in Berkeley, California) for sending a free copy for review.