Blog Tour: Extract from The Power of Dog by Andrew G. Marshall

Last April I participated in the blog tour for Andrew G. Marshall’s previous book, My Mourning Year, a memoir about the death of his partner Thom and his journey through grief.

Last April I participated in the blog tour for Andrew G. Marshall’s previous book, My Mourning Year, a memoir about the death of his partner Thom and his journey through grief.

The Power of Dog is like a sequel; it tells what happened when Andrew acquired a collie cross puppy named Flash.

Alas, a copy didn’t arrive in time for me to read it before I left for America, but to open up the blog tour today I have an extract for you, and I look forward to reading the book when I get back.

Prologue

What I wanted most and what frightened me most, when I was a child, turned out to be the same thing. Every year as I blew out my birthday cake candles, I’d wish for a puppy ‒ with my eyes tightly closed to maximise the magic. But while my daydreams were full of adoring Labradors fetching sticks, my nightmares were stalked by their distant relatives: wolves.

My parents belonged to the ‘comfortably off’ middle classes and were only too happy to pay for tennis lessons, new bikes and summer camp – indeed they were particularly keen to send me to these. My birthday cake was always home baked, a fruit cake decorated with teddy bears sitting in a spiky snow scene. Despite the growing number of candles and my entreaties, the gods of birthday wishes were unmoved. Although my mother agreed first to guinea pigs and later mice, she remained firm about getting a dog: ‘I’ll be the one who ends up walking it.’

I can pinpoint the exact moment the nightmares started. Our next-door neighbours, whom I’d christened H’auntie and H’uncle, had retired to Bournemouth and one summer we stayed overnight at their house. I must have been four or five and already possessed a vivid imagination. In the middle of the night, I had to tiptoe across an unfamiliar landing to the lavatory ‒ never toilet because my mother considered the term vulgar. Returning, I closed the bedroom door as quietly as possible and revealed a large hairy wolf ready to pounce. I can’t remember if I screamed or whether anybody came. Maybe my mother pointed out that the wolf was really a man’s woollen winter dressing gown hanging on a hook; all of those details have been forgotten but I can still remember the nightmares.

Back home in Northampton, I slept in a tall wooden bed which had originally belonged to my father. The mattress and the springs were so old that they had sunk to form a hollow which fitted exactly around my small body. I felt safe nestling between the two hills on either side. However, the old-fashioned design left a large amount of space under the bed. By day, this space housed a box of favourite toys, but at night I never had the nerve to lift the white candlewick counterpane. I instinctively knew the wolves had set up camp there. The rules of engagement were simple: I was safe in bed, but they could pounce and catch me if I didn’t run fast enough back from the loo ‒ an acceptable abbreviation. On particularly dark nights, the wolves would emerge from their lair and dance round the room with their teeth glinting in the moonlight. I’d scream out and Mummy would come and reassure me:

‘The wolves will not get you.’

She would lift the counterpane and show me.

‘There’s nothing there.’

It was easy for her to say – the wolves would disappear as soon as she’d open my bedroom door. But after she’d told me to ‘sleep tight’ and gone back to bed, they would rematerialise, slink back into the lair and an uneasy truce would be established.

Wolves did not have a monopoly on my fears. For a while in the sixties a ‘cop killer’ called Harry Roberts evaded the police by haunting my nightmares. If there was a strange-looking man drinking alone at the rugby club bar ‒ where my father was treasurer ‒ I would sidle up to one of my parents and whisper: ‘THERE’S HARRY ROBERTS.’ It must have been embarrassing for my parents, but in defence of my seven-year-old self, the rugby club did attract an odd crowd.

Fortunately, my fear of Harry Roberts was easy to cure. One night in 1966, I was allowed to stay up late to watch his capture on the news. I can still picture the small makeshift camp in the woods ‒ the blanket strung between three trees and the discarded tin cans ‒ but not where (except it was many miles from my home). I slept soundly that night.

Flushed by her success with Harry Roberts, my mother took me to London Zoo. I was softened up with lions, monkeys and possibly even a ride on an elephant. Next, she casually mentioned that they had wolves too. I can’t remember what I was wearing but I can picture myself in an anorak so large it came down past my knees ‒ ‘you’ll grow into it’ – being taken to an enclosure hidden in some back alley of the Zoo. Did I actually look at the wolves? Perhaps I refused. Perhaps they were asleep in their den. Whatever happened next, the pack under my bed would not be exorcised so easily.

At that age it was impossible to believe I would ever reach ten; but I did. I even turned eighteen and left home for university where I studied Politics and Sociology. After graduating, I got a job first at BRMB Radio in Birmingham (in the newsroom) and then Essex Radio in Southend (as a presenter and producer) and Radio Mercury in Crawley (where I rose to become Deputy Programme Controller). My nightmares about wolves had long since ended, but if they appeared on TV they would still make me feel uneasy and I would switch channels. I still wanted a dog, but I was far too practical. I had a career to pursue. Who would walk the dog? Would it be fair to leave it alone while I worked? I couldn’t be tied down by such responsibilities.

At thirty, I fell in love with Thom and we talked about getting a dog together. However, for the first four and a half years, he lived in Germany and I lived in Hurstpierpoint (a small Sussex village). In the spring of 1995, Thom finally moved over to England with plans to set up an interior design company. However, six months later, he fell ill. All our plans for dog-owning were put on hold, while we concentrated on getting him better. He spent months in hospital first in England and then in Germany and I spent a lot of time flying backwards and forwards between the two countries. I loved Thom with a passion that sometimes terrified me, so when he died, on 9 March 1997, I was completely inconsolable.

I moved into the office he’d created in our spare room, but I couldn’t stop the computer from still sending faxes from Andrew Marshall and Thom Hartwig. As far as Microsoft Word was concerned, he was immortal. I tried various strategies to cope with my bereavement but three different counsellors did not shift it. Two short-term relationships made me feel worse not better. I had just turned forty. My regular sources of income – being Agony Uncle for Live TV and writing a column for the Independent newspaper – were both terminated. My grief was further isolating me and many of Thom’s and my couple friendships had just withered away.

Approaching the Millennium, something had to change, but what?

The Power of Dog will be released by RedDoor Publishing on Thursday, July 12th. My thanks to the publisher for a review copy.

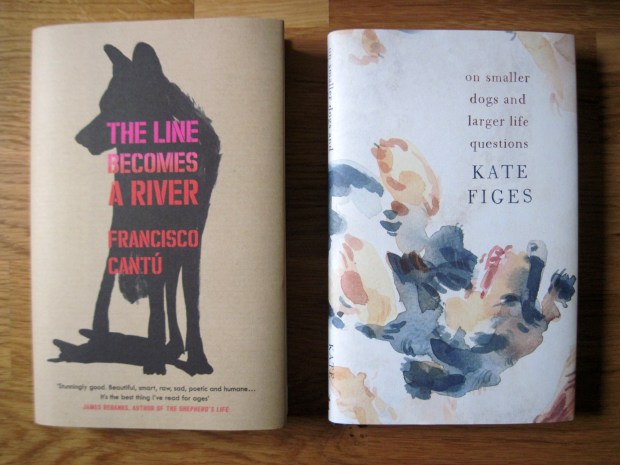

Two Memoirs: Border Control and Breast Cancer

The Line Becomes a River

Francisco Cantú was a U.S. Border Patrol agent in Arizona and Texas for four years. Agents tracked illegals using the same skills with which hunters stalk their prey. Once captured, the would-be immigrants were detained, processed and deported. Days in the field were full of smuggled drugs, cached belongings and corpses of those who’d tried to cross in inhospitable conditions. Even when Cantú was transferred to a desk job, he couldn’t escape news of Mexican drug cartels and ritual mutilation of traitors’ corpses. Dreams of wolves and of his teeth breaking and falling out revealed that this was a more stressful career than he ever realized. Cantú worried that he was becoming inured to the violence he encountered daily – was he using his position “as a tool for destruction or as one of safekeeping”?

Impressionistic rather than journalistic, the book is a loosely thematic scrapbook that uses no speech marks, so macho banter with colleagues blends into introspection, memories and stories. Cantú inserts snippets of U.S.–Mexico history, including the establishment of the border, and quotes from and discusses other primary and secondary texts. He also adds in fragments of his family’s history: His ancestors left Mexico during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, but there’s no doubt his Latino name and features made him a friendly face for illegal immigrants. He was often called upon to translate for those in custody. I felt that even if the overall policy was problematic, it was good to have someone compassionate in his job.

Impressionistic rather than journalistic, the book is a loosely thematic scrapbook that uses no speech marks, so macho banter with colleagues blends into introspection, memories and stories. Cantú inserts snippets of U.S.–Mexico history, including the establishment of the border, and quotes from and discusses other primary and secondary texts. He also adds in fragments of his family’s history: His ancestors left Mexico during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, but there’s no doubt his Latino name and features made him a friendly face for illegal immigrants. He was often called upon to translate for those in custody. I felt that even if the overall policy was problematic, it was good to have someone compassionate in his job.

The final third of the book represents a change of gears: Cantú left law enforcement to be a Fulbright scholar and then embarked on an MFA in creative writing at the University of Arizona. During those years of study he worked as a barista at a food court and every day he chatted and shared food with another worker, José Martínez from Oaxaca. When José went back to Mexico to visit his dying mother and settle her estate, he was refused reentry to the United States for not having the proper papers. Cantú drew on his contacts in Border Patrol to find out when José’s hearing would be, helped his wife to gather character witness letters, and took José’s sons to visit him in the detention center during his continuance and civil trial. There’s a particularly wrenching recreated monologue from José himself.

I love these endpapers.

It is as if, for the first time, Cantú could see the human scale of U.S. immigration policy, what his mother, a former national park ranger, had described as “an institution with little regard for people.” No longer could he be blasé about the way things are. It was also, he recognized, an attempt to atone for the heartless deportations he had conducted as a Border agent. “All these years,” he said to his mother, “it’s like I’ve been circling beneath a giant, my gaze fixed upon its foot resting at the ground. But now, I said, it’s like I’m starting to crane my head upward, like I’m finally seeing the thing that crushes.” As he quotes from Holocaust historian Timothy Snyder, “It is for us as humanists to turn the numbers back into people.” That’s just what this remarkable memoir does. In giving faces to an abstract struggle, it passionately argues that people should not be divided by walls but united in common humanity.

My rating:

The Line Becomes a River was published in the UK by Bodley Head on March 1st. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

On Smaller Dogs and Larger Life Questions

It was hard to resist such a great title, especially with my penchant for cancer memoirs. In nine chapters that are almost like linked essays, Kate Figes reflects on the changes that a diagnosis of triple-negative, metastasized breast cancer has wrought in her life. However, like Vesna Goldsworthy’s Chernobyl Strawberries, the book sets the cancer experience within a wider life story of trauma and displacement. In the first essay, as Figes, a freelance nonfiction writer, approached age 60, she delighted in Zeus, their miniature wire-haired dachshund puppy, but also resented the sense of obligation. Cancer quickly changed her perspective.

I appreciated the lack of bitterness; the book’s focus is generally on resilience and on the liberation of knowing that little is now expected of her: “when there is no need to rush just to be able to get through everything I had to achieve each day, there is a glorious sense of freedom, of empty space.” Two chapters go in-depth into Figes’s “arsenal” of cancer-fighting tools, everything from hyperbaric oxygen treatments to yoga. She gave up sugar and swears by cannabis oil, filtered water, supplements and fresh juices. Her embrace of complementary medicine and discussion of her limitations – it takes her an hour and a half to get dressed and have breakfast – will probably mean the most to others with a chronic illness.

I appreciated the lack of bitterness; the book’s focus is generally on resilience and on the liberation of knowing that little is now expected of her: “when there is no need to rush just to be able to get through everything I had to achieve each day, there is a glorious sense of freedom, of empty space.” Two chapters go in-depth into Figes’s “arsenal” of cancer-fighting tools, everything from hyperbaric oxygen treatments to yoga. She gave up sugar and swears by cannabis oil, filtered water, supplements and fresh juices. Her embrace of complementary medicine and discussion of her limitations – it takes her an hour and a half to get dressed and have breakfast – will probably mean the most to others with a chronic illness.

As to the other essays, “Tennis” is an ode to a favorite hobby she had to give up; “Mediation” is about training as a family mediator. The psychological understanding she gained through this and through researching her books helped her work through childhood hurt over her parents’ divorce. “The Beach Hut” remembers recent ‘escapes’ to the seaside and contrasts them with her Jewish mother’s* escape from 1930s Germany. “Home,” my favorite essay, is about clearing out her mother’s flat and the memories and comfort a home retains, even decades later. “That’s the power I will leave behind too, the essence of having been really known. It will pervade every piece of crockery I have eaten off, … every chair I have sat on.”

Unfortunately, Figes frequently uses clichéd language – “Cancer can feel isolating” and “battle is the right word” – and seems to give credence to the damaging idea that unresolved emotional trauma caused her cancer. What with the typos and the slight repetition across the essays, this feels like a book that was put together in a hurry. A bit more time and editing could have made it more cohesive and fresh. But perhaps Figes does not have that time. Fellow cancer patients may well appreciate her dispatches from what she calls “Planet Cancer,” but it’s not a book that will particularly stand out for me in this crowded genre.

*Her mother was Eva Figes, an author in her own right.

My rating:

On Smaller Dogs and Larger Life Questions was published by Virago on February 28th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Some Accidental Thematic Overlaps in My Recent Reading

Five of the books I’ve read recently (most of them while traveling to and from the States) have shared an overarching theme of loss, with mental illness, alcoholism, suicide, and dogs as subsidiary topics running through two or more of them. I hadn’t deliberately chosen these books for their commonalities, so it was uncanny to see the same elements keep popping up. I wanted to come up with some kind of impressively complex Venn diagram to show off these unexpected connections but couldn’t quite manage it, so you’ll have to imagine it instead.

Mental Illness

The Archivist by Martha Cooley

Matthias Lane is the archivist of the Mason Room, a university collection of rare books and literary papers. One of its treasures is a set of letters that passed between T.S. Eliot and his friend Emily Hale (held at Princeton in real life). Matt is haunted by memories of his late wife, Judith, a poet incarcerated in a mental hospital for over five years. A reckoning comes for Matt when he’s approached by Roberta Spire, a graduate student determined to view the Eliot–Hale letters even though they’re legally sealed until 2020. The more time Matt spends with Roberta, the more similarities start to arise between her and Judith; and between his situation and Eliot’s when the latter also put his wife away in a mental hospital. The novel asks what we owe the dead: whether we conform to their wishes or make our own decisions.

Matthias Lane is the archivist of the Mason Room, a university collection of rare books and literary papers. One of its treasures is a set of letters that passed between T.S. Eliot and his friend Emily Hale (held at Princeton in real life). Matt is haunted by memories of his late wife, Judith, a poet incarcerated in a mental hospital for over five years. A reckoning comes for Matt when he’s approached by Roberta Spire, a graduate student determined to view the Eliot–Hale letters even though they’re legally sealed until 2020. The more time Matt spends with Roberta, the more similarities start to arise between her and Judith; and between his situation and Eliot’s when the latter also put his wife away in a mental hospital. The novel asks what we owe the dead: whether we conform to their wishes or make our own decisions.

The Summer without Men by Siri Hustvedt

Thirty years on, poet Mia Fredricksen’s husband Boris asks her for a pause in their marriage so he can explore his feelings for his young French lab assistant. First things first: Mia goes crazy and ends up in a mental hospital for a short time. But then she sucks it up and goes back to her Minnesota hometown to teach poetry writing to teen girls for a summer, getting sucked into a bullying drama. This is a capable if not groundbreaking story of the shifts that occur in a long marriage and the strange things we all do as we face down the possibility of death. There are also wry comments about the unappreciated talents of the female artist. However, compared to the other two novels I’ve read from Hustvedt, this seemed feeble. Still, a quick and enjoyable enough read.

Thirty years on, poet Mia Fredricksen’s husband Boris asks her for a pause in their marriage so he can explore his feelings for his young French lab assistant. First things first: Mia goes crazy and ends up in a mental hospital for a short time. But then she sucks it up and goes back to her Minnesota hometown to teach poetry writing to teen girls for a summer, getting sucked into a bullying drama. This is a capable if not groundbreaking story of the shifts that occur in a long marriage and the strange things we all do as we face down the possibility of death. There are also wry comments about the unappreciated talents of the female artist. However, compared to the other two novels I’ve read from Hustvedt, this seemed feeble. Still, a quick and enjoyable enough read.

The Dogs of Babel by Carolyn Parkhurst

A delicious debut novel intellectual enough to bypass labels like ‘women’s fiction’ and ‘mystery’. One thing that sets it apart is how successfully Parkhurst writes from the perspective of a male narrator, Paul Iverson, who’s been knocked for six by the sudden death of his wife Lexy, a mask designer. While he was at the university where he teaches linguistics, she climbed to the top of the apple tree in their backyard and – what? fell? or jumped? The only ‘witness’ was their Rhodesian Ridgeback, Lorelei; in his grief Paul uses his sabbatical to research efforts to teach dogs to communicate, hoping one day Lorelei might tell all. Woven through are scenes from Paul and Lexy’s courtship and marriage; though Lexy occasionally struggled with her mental health, their dialogue is fun and zippy, like you might hear on The Gilmore Girls.

A delicious debut novel intellectual enough to bypass labels like ‘women’s fiction’ and ‘mystery’. One thing that sets it apart is how successfully Parkhurst writes from the perspective of a male narrator, Paul Iverson, who’s been knocked for six by the sudden death of his wife Lexy, a mask designer. While he was at the university where he teaches linguistics, she climbed to the top of the apple tree in their backyard and – what? fell? or jumped? The only ‘witness’ was their Rhodesian Ridgeback, Lorelei; in his grief Paul uses his sabbatical to research efforts to teach dogs to communicate, hoping one day Lorelei might tell all. Woven through are scenes from Paul and Lexy’s courtship and marriage; though Lexy occasionally struggled with her mental health, their dialogue is fun and zippy, like you might hear on The Gilmore Girls.

Suicide

The Archivist by Martha Cooley & The Dogs of Babel by Carolyn Parkhurst

Alcoholism

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight by Alexandra Fuller

A classic memoir that conjures up all the sights, sounds, smells and feelings of Africa on the cusp of a colonial to postcolonial transition. Fuller’s family were struggling tobacco and cattle farmers in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Malawi and Zambia. She had absorbed the notion that white people were there to benevolently shepherd the natives, but came to question it when she met Africans for herself. While giving a sense of the continent’s political shifts, she mostly focuses on her own family: the four-person circus that was Bobo (that’s her), Van (older sister Vanessa), Dad, and Mum (an occasionally hospitalized manic-depressive alcoholic who lost three children) – not to mention an ever-changing menagerie of horses, dogs and other pets. This really takes you away to another place and time, as the best memoirs do, and the plentiful black-and-white photos are a great addition.

A classic memoir that conjures up all the sights, sounds, smells and feelings of Africa on the cusp of a colonial to postcolonial transition. Fuller’s family were struggling tobacco and cattle farmers in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Malawi and Zambia. She had absorbed the notion that white people were there to benevolently shepherd the natives, but came to question it when she met Africans for herself. While giving a sense of the continent’s political shifts, she mostly focuses on her own family: the four-person circus that was Bobo (that’s her), Van (older sister Vanessa), Dad, and Mum (an occasionally hospitalized manic-depressive alcoholic who lost three children) – not to mention an ever-changing menagerie of horses, dogs and other pets. This really takes you away to another place and time, as the best memoirs do, and the plentiful black-and-white photos are a great addition.

Let’s Take the Long Way Home by Gail Caldwell

If you loved Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty, pick this up immediately. It’s a similar story of best friends: one who dies and one who survives. Caldwell’s best friend was Caroline Knapp (author of Drinking: A Love Story, among other nonfiction), whom she met via puppy ownership in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They were both single and childless, full-time authors with a history of alcoholism. Besides long walks with their dogs, they loved swimming and rowing together. In 2002 Caroline was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer, inoperable and already metastasized. Despite all their proactive optimism, she was dead a matter of weeks later. In this moving and accessible short memoir, Caldwell drifts through her past, their friendship, Caroline’s illness, and the years of grief that followed the loss of Caroline and then her beloved Samoyed, Clementine, sharing what she learned about bereavement.

If you loved Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty, pick this up immediately. It’s a similar story of best friends: one who dies and one who survives. Caldwell’s best friend was Caroline Knapp (author of Drinking: A Love Story, among other nonfiction), whom she met via puppy ownership in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They were both single and childless, full-time authors with a history of alcoholism. Besides long walks with their dogs, they loved swimming and rowing together. In 2002 Caroline was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer, inoperable and already metastasized. Despite all their proactive optimism, she was dead a matter of weeks later. In this moving and accessible short memoir, Caldwell drifts through her past, their friendship, Caroline’s illness, and the years of grief that followed the loss of Caroline and then her beloved Samoyed, Clementine, sharing what she learned about bereavement.

Dogs

The Dogs of Babel, Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight & Let’s Take the Long Way Home

It was my first time reading the famous “The Garden Party,” which likewise moves from a blithe holiday mood into something weightier. The Sheridans are making preparations for a lavish garden party dripping with flowers and food. Daughter Laura is dismayed when news comes that a man from the cottages has been thrown from his horse and killed, and thinks they should cancel the event. Everyone tells her not to be silly; of course it will go on as planned. The story ends when, after visiting his widow to hand over leftover party food, she unwittingly sees the man’s body and experiences an epiphany about the simultaneous beauty and terror of life. “Don’t cry,” her brother says. “Was it awful?” “No,” she replies. “It was simply marvellous.” Mansfield is especially good at first and last paragraphs. I’ll read more by her someday.

It was my first time reading the famous “The Garden Party,” which likewise moves from a blithe holiday mood into something weightier. The Sheridans are making preparations for a lavish garden party dripping with flowers and food. Daughter Laura is dismayed when news comes that a man from the cottages has been thrown from his horse and killed, and thinks they should cancel the event. Everyone tells her not to be silly; of course it will go on as planned. The story ends when, after visiting his widow to hand over leftover party food, she unwittingly sees the man’s body and experiences an epiphany about the simultaneous beauty and terror of life. “Don’t cry,” her brother says. “Was it awful?” “No,” she replies. “It was simply marvellous.” Mansfield is especially good at first and last paragraphs. I’ll read more by her someday.