Recent Nonfiction Reads, in 200 Words Each: Black, Fee, Gaw

I’ve let months pass between receiving these books from the kindly publishers and following through with a review, so in an attempt to clear the decks I’m putting up just a short response to each, along with some favorite quotes.

All that Remains: A Life in Death by Sue Black

Black, a world-leading forensic anthropologist, was part of the war crimes investigation in Kosovo and the recovery effort in Thailand after the 2004 tsunami. She is frequently called into trials to give evidence, has advised the U.K. government on disaster preparedness, and is a co-author of the textbook Developmental Juvenile Osteology (2000). Whether working in a butcher’s shop as a teenager or exploring a cadaver for an anatomy class at the University of Aberdeen, she’s always been comfortable with death. “I never had any desire to work with the living,” she confesses; “The dead are much more predictable and co-operative.”

Black, a world-leading forensic anthropologist, was part of the war crimes investigation in Kosovo and the recovery effort in Thailand after the 2004 tsunami. She is frequently called into trials to give evidence, has advised the U.K. government on disaster preparedness, and is a co-author of the textbook Developmental Juvenile Osteology (2000). Whether working in a butcher’s shop as a teenager or exploring a cadaver for an anatomy class at the University of Aberdeen, she’s always been comfortable with death. “I never had any desire to work with the living,” she confesses; “The dead are much more predictable and co-operative.”

The book considers death in its clinical and personal aspects: the seven stages of postmortem alteration and the challenges of identifying the sex and age of remains; versus her own experiences with losing her grandmother, uncle and parents. Black wants her skeleton to go to Dundee University’s teaching collection. It doesn’t creep her out to think of that, no more than it did to meet her future cadaver, a matter-of-fact, curious elderly gentleman named Arthur. My favorite chapter was on Kosovo; elsewhere I found the mixture of science and memoir slightly off, and the voice never fully drew me in.

Favorite line: “Perhaps forensic anthropologists are the sin-eaters of our day, addressing the unpleasant and unimaginable so that others don’t have to.”

My rating:

All that Remains was published by Doubleday on April 19th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Places I Stopped on the Way Home: A Memoir of Chaos and Grace by Meg Fee

Fee came to New York City to study drama at Julliard. Her short essays, most of them titled after New York locations (plus a few set further afield), are about the uncertainty of her twenties: falling in and out of love, having an eating disorder, and searching for her purpose. She calls herself “a mess of disparate wants, a small universe in bloom.” New York is where she has an awful job she hates, can’t get the man she’s in love with to really notice her, and hops between terrible apartments – including one with bedbugs, the subject of my favorite essay – and yet the City continues to lure her with its endless opportunities.

Fee came to New York City to study drama at Julliard. Her short essays, most of them titled after New York locations (plus a few set further afield), are about the uncertainty of her twenties: falling in and out of love, having an eating disorder, and searching for her purpose. She calls herself “a mess of disparate wants, a small universe in bloom.” New York is where she has an awful job she hates, can’t get the man she’s in love with to really notice her, and hops between terrible apartments – including one with bedbugs, the subject of my favorite essay – and yet the City continues to lure her with its endless opportunities.

I think this book could mean a lot to women who are younger than me or have had experiences similar to the author’s. I found the essays slightly repetitive, and rather unkindly wondered what this privileged young woman had to whine about. It’s got the same American, generically spiritual self-help vibe that you get from authors like Brené Brown and Elizabeth Gilbert. Despite her loneliness, Fee retains a romantic view of things, and the way she writes about her crushes and boyfriends never truly connected with me.

Some favorite lines:

“Writing felt like wrangling storm clouds, which is to say, impossible. But so did life. Writing became a way to make peace with that which was flawed.”

“I have let go of the idea of permanency and roots and What Comes Next.”

My rating:

Places I Stopped on the Way Home was published by Icon Books on May 3rd. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

The Pull of the River: A journey into the wild and watery heart of Britain by Matt Gaw

A watery travelogue in the same vein as works by Roger Deakin and Alys Fowler, this jolly yet reflective book traces Gaw’s canoe trips down Britain’s rivers. His vessel was “the Pipe,” a red canoe built by his friend James Treadaway, who also served as his companion for many of the jaunts. Starting with his local river, the Waveney in East Anglia, and finishing with Scotland’s Great Glen Way, the quest was a way of (re)discovering his country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger.

A watery travelogue in the same vein as works by Roger Deakin and Alys Fowler, this jolly yet reflective book traces Gaw’s canoe trips down Britain’s rivers. His vessel was “the Pipe,” a red canoe built by his friend James Treadaway, who also served as his companion for many of the jaunts. Starting with his local river, the Waveney in East Anglia, and finishing with Scotland’s Great Glen Way, the quest was a way of (re)discovering his country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger.

Access issues, outdoor toileting, getting stuck on mudflats, and going under in the winter – it wasn’t always a comfortable method of travel. But Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful in their own way: “grim bunting made from discarded bags of dog poo,” “a savannah of quivering, moussey mud” and “cormorants hunched together like sinister penguins, some holding ragged wings to the wind in taxidermic poses.”

My favorite chapters were about pollution and invasive species, as seen at the Lark, and about the beaver reintroduction project in Devon (we have friends who live near it). I’m rooting for this to make next year’s Wainwright Prize longlist.

A favorite passage:

“I feel like I’ve shed the rust gathered from being landlocked and lazy. The habits and responsibilities of modern life can be hard to shake off, the white noise difficult to muffle. But the water has returned me to my senses. I’ve been reborn in a baptism of the Waveney [et al.]”

My rating:

The Pull of the River was published by Elliott & Thompson on April 5th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Have you read any stand-out nonfiction recently?

Blog Tour & Giveaway: The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities

I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: A Yearbook of Forgotten Words by Paul Anthony Jones, which will be published in the UK by Elliott & Thompson on Thursday, October 19th.

I started reading these delightful daily doses of etymology last week, and plan to keep the book at my bedside for the whole of the year to come. By happy coincidence, today is also my birthday, so (if I may so flatter myself) in joint honor of the occasion plus the book’s impending publication, Elliott & Thompson have kindly offered a giveaway copy to one UK-based reader.

Enjoy today’s entry, and leave a comment if you’d like to be in the running for the giveaway. I will choose the winner at random at the end of Saturday the 21st and notify them via e-mail.

14 October

Parthian (adj.) describing or akin to a shot fired while in retreat

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066. Exhausted and depleted from fighting the Battle of Stamford Bridge just nineteen days earlier, the English King Harold’s forces were eventually overcome by those of the invading Norman King William when they began to implement an ingenious and effective tactic. Reportedly, William’s troops pretended to flee from the battle in panic, and as their English attackers pursued them, the Normans suddenly turned back and resumed fighting.

The Normans and their allies, observing that they could not overcome an enemy which was so numerous and so solidly drawn up, without severe losses, retreated, simulating flight as a trick . . . Suddenly the Normans reined in their horses, intercepted and surrounded [the English] and killed them to the last man.

William of Poitiers, Gesta Guillelmi (c.1071)

The Normans weren’t the first to use such a tactic; fighters in ancient Parthia, a region of northeast Iran, were known to continue firing arrows at their enemies while retreating from the battlefield. The ploy proved so effective that the adjective Parthian ultimately came to be used of any shot or attack employed while in retreat, or in the dying moments of an engagement. In that sense, the word first appeared in English in the mid seventeenth century, but while the technique they employed remained familiar, the Parthians themselves did not. Ultimately, the word Parthian became corrupted, and steadily drifted closer to a much more familiar term – so that today this kind of last-minute attack or sally is typically known as a parting shot.

Britain’s Bounty: Land of Plenty by Charlie Pye-Smith

Charlie Pye-Smith is a farming and environmental commentator with many previous titles to his name. To research this survey of modern food production, he spent a year traveling around the British countryside in a motor home, interviewing farmers and manufacturers and learning how things are likely to change when Brexit takes effect. In the face of surpluses and falling profits, he suggests that in the future farmers will need to diversify. Questioning received wisdom, he also proposes that animal welfare might be more achievable in larger-scale operations and that environmentally friendly techniques like crop rotation might actually lead to higher yields.

Many of the farms the author visits have survived due to their adaptability. For instance, the Belchers of Leicestershire found they could double their profits if they processed their cattle, pigs and lambs themselves and sold the meat at farmer’s markets. Likewise, the Blands, dairy farmers in Cumbria, branched out after they lost their whole herd to foot-and-mouth disease in 2001: Now they produce ice cream from their Jersey cows and run a successful tea room. On the other hand, specializing in a heritage product can also be an effective strategy. In Yorkshire, the author meets farmers who have been raising sheep locally for centuries. “It’s all about eating the view … linking Swaledale sheep to a beautiful upland landscape. Eat our lamb and you’re helping to protect the Dales,” is the message.

Many of the farms the author visits have survived due to their adaptability. For instance, the Belchers of Leicestershire found they could double their profits if they processed their cattle, pigs and lambs themselves and sold the meat at farmer’s markets. Likewise, the Blands, dairy farmers in Cumbria, branched out after they lost their whole herd to foot-and-mouth disease in 2001: Now they produce ice cream from their Jersey cows and run a successful tea room. On the other hand, specializing in a heritage product can also be an effective strategy. In Yorkshire, the author meets farmers who have been raising sheep locally for centuries. “It’s all about eating the view … linking Swaledale sheep to a beautiful upland landscape. Eat our lamb and you’re helping to protect the Dales,” is the message.

Pye-Smith also looks into pig welfare and plowing techniques for cereal crops. In a chapter on fruit, he tells the recent story of apples and strawberries through cider and jam production, respectively. A section on vegetables centers on potatoes. I learned a number of facts that surprised me:

- Over half Britain’s potatoes are turned into crisps and chips

- “Outdoor-reared” pork is not necessarily the ideal because cold, wet winters are tough on piglets and sows

- Cider coming into fashion over the last 10–15 years is largely thanks to Magners’ advertising campaigns

- Nowadays the average Briton spends just 10% of their income on food, as opposed to 33% in the 1950s.

The book strikes an appropriate balance between the cutting-edge and the traditional, and between caution and optimism. Although Brexit will lead to a total loss of farmers’ EU subsidies and a drop in the number of Eastern Europeans coming over to pick produce, there may be potential benefits too. As one large-scale vegetable farmer opines, “we should see Brexit as a great opportunity to promote home-grown food production.” I appreciated how open the author is to organic and conservation agriculture, but he also doesn’t present them as magical solutions. For the most part, I sensed no hidden agenda, though he is perhaps pro-grouse shooting and seems dismissive of city journalists like George Monbiot who claim to know better than the real countryside experts.

This is most like a condensed, British version of Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma; Pye-Smith makes the same sort of investigations into food production methods, including tiny snippets from his own life along the way. Crucially, the book is readable throughout, never sinking into tedious statistics or jargon. The author’s black-and-white photographs, three to five per chapter, are a nice addition. In essence this is a collection of stories about a way of life that faces challenges but is not doomed. I was reassured to hear that people increasingly care about where their food comes from. Martin Thatcher of Thatchers cider says “People have become more discriminating. They are now much more interested in what they’re eating and drinking than they were in the past, and how it’s produced.” If you, too, are interested in how food gets to you in Britain, be sure to pick up this book.

My rating:

Land of Plenty is published today, July 27th, by Elliott & Thompson. Thanks to Alison Menzies for arranging my free copy for review.

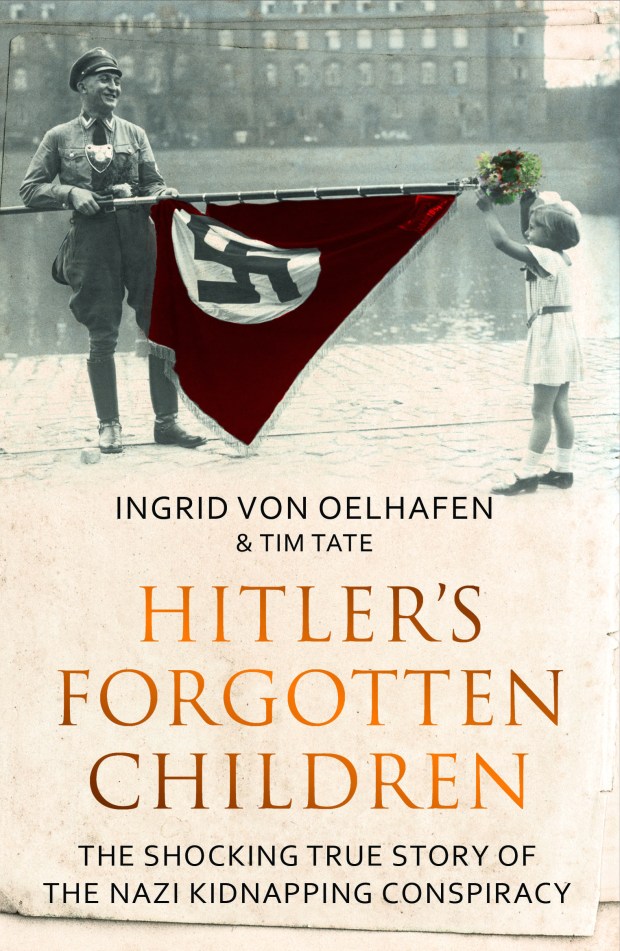

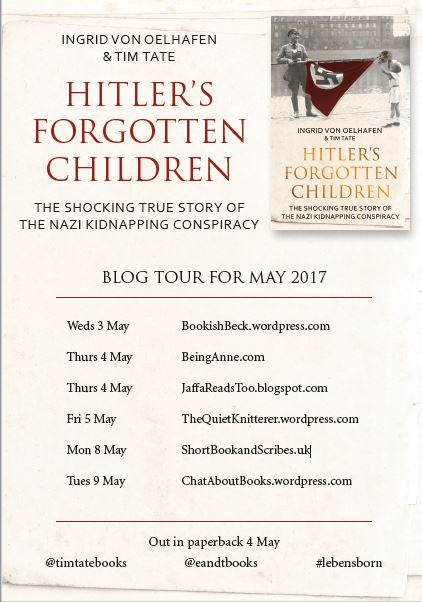

Giveaway: Hitler’s Forgotten Children

Tomorrow Elliott & Thompson are releasing the paperback edition of Hitler’s Forgotten Children by Ingrid von Oelhafen and Tim Tate, a powerful first-person account from a child of the Lebensborn: the Nazis’ program to create an Aryan master race.

The publisher has kindly offered a free copy to one of my readers.

Here’s a bit more information about the book, adapted from the press release:

Forcibly adopted into a Nazi family as part of the Lebensborn program, Ingrid’s heartbreaking story is a quest for identity and an important historical document touching on the untold stories of thousands like her.

By the 1940s, Himmler’s breeding program had failed to provide adequate numbers of ‘racially pure and healthy’ children, so Lebensborn sought to boost the flagging German population by sinister means. Children in the occupied territories were examined and any exhibiting ‘Aryan’ qualities were forcibly taken from their parents to be raised by the regime.

In 1942 Erika, a baby girl from Yugoslavia, was examined by the Nazi occupiers, declared an ‘Aryan’ and removed from her mother. Her true identity erased, she became Ingrid von Oelhafen. Later, as Ingrid began to uncover her true identity, the full scale of the Lebensborn scheme became clear – including the kidnapping of up to half a million babies like her, and the deliberate murder of children born into the program who were deemed ‘substandard’.

We learn of Ingrid’s subsequent troubled childhood in Germany; first during the war, then a harrowing escape from the GDR, time in children’s homes and the shock of discovering as a teenager that she was adopted. Later, the search for the truth took her to Nuremberg Trials records and, ultimately, back to Yugoslavia, where she discovered the full story: the Nazis substituted ‘Ingrid’ with another child who was raised as ‘Erika’ by her family.

And here’s an exclusive extract:

Cilli, German-occupied Yugoslavia, 3–7 August 1942

The schoolyard was crowded. Hundreds of women – young and old – clutched the hands of their children and found what space they could in the packed courtyard. Nearby, Wehrmacht soldiers, rifles slung over their shoulders, looked on as the families slowly drifted in from towns and villages across the area. These women had been summoned by their new German masters, ordered to bring their children to the school for ‘medical tests’. Upon arrival they were arrested and told to wait. Otto Lurker, commander of the police and security services for the region, watched relaxed and impassive – his hands resting comfortably in his pockets – as the yard filled with families. Once, Lurker had been Hitler’s gaoler: now he was the Führer’s leading henchman in Lower Styria. He held the rank of SS-Standartenführer – the paramilitary equivalent of a full colonel in the army – but that summer’s morning he was casually dressed in a two-piece civilian suit.

Among them was a family from the nearby village of Sauerbrunn. Johann Matko came from a family of known partisans: his brother, Ignaz, had been one of those lined up and shot against the wall of Cilli prison in July. Johann had been dragged off to Mauthausen concentration camp. After seven months in the camp he was allowed to return home to his wife, Helena, and their three children: eight-year-old Tanja, her brother Ludvig – then six – and nine-month-old baby Erika. When all the families were accounted for, an order was given to separate them into three groups – one each for the children, the women, and the men.

Under Lurker’s direction the soldiers moved in and pulled children from the grasp of their mothers; a local photographer, Josip Pelikan, recorded the harrowing scene for the Reich’s obsessive archivists. His rolls of film captured the fear and alarm of women and children alike: his shots included scores of toddlers held in low pens of straw inside the school buildings. As the mothers waited outside, Nazi officials began a cursory examination of the children.

Working with charts and clipboards, they painstakingly noted each child’s facial and physical characteristics. These, though, were not ‘medical tests’ as any doctor would know them: instead they were crude assessments of ‘racial value’ which assigned each youngster to one of four categories. Those who met Himmler’s strict criteria for what a child of true German blood should look like were placed in Category 1 or 2: this formally registered them as potentially useful additions to the Reich population.

By contrast, any hint or trace of Slavic features – and certainly any sign of ‘Jewish heritage’– consigned a child to the lowest racial status of Categories 3 and 4. Thus branded as Untermensch, their value was no more than future slave labour for the Nazi state. By the following day this rudimentary sifting had finished. Those children deemed racially worthless were handed back to their families. But 430 other youngsters, from young babies to twelve-year-old boys and girls, were taken away by their captors. Marshalled by nurses from the German Red Cross, they were packed into trains and transported across the Yugoslavian border to an Umsiedlungslager – or transit camp – at Frohnleiten, near the Austrian town of Graz.

They did not stay long in this holding centre. By September 1942, a further selection had been made – this time by trained ‘race assessors’ from one of the myriad organisations established by Himmler to preserve and strengthen the pool of ‘good blood’. Noses were measured and compared to the official ideal length and shape; lips, teeth, hips and genitals were likewise prodded, poked and photographed to sort the genetically precious human wheat from the less-valuable chaff.

This finer, more rigorous sieving re-assigned the captives within the four racial categories. Older children newly listed in Categories 3 or 4 were shipped off to re-education camps across Bavaria in the heartland of Nazi Germany. The best of the younger ones in the top two categories would – in time – be handed over to a secretive project run by the Reichsführer himself. Its name was Lebensborn and among the infants assigned to its care was nine-month-old Erika Matko.

If you’re interested in winning a paperback copy of Hitler’s Forgotten Children, simply leave a comment to that effect below. The competition will be open through the end of Friday the 12th and I will choose a winner at random on Saturday the 13th (announced via the comments and a personal e-mail). Sorry, U.K. entries only. Good luck!

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the paperback release blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features will be appearing soon.

Autumn Is Here, in Poetry and Prose

“The trees are undressing, and fling in many places –

On the gray road, the roof, the window-sill –

Their radiant robes and ribbons and yellow laces”

~from “Last Week in October,” Thomas Hardy (1928)

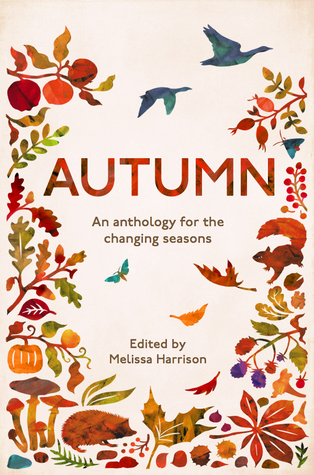

I recently learned that there are two different official start dates for autumn. The meteorological beginning of the season was on September 1st, while the astronomical opening is not until the 22nd. For the purposes of this review I’ll incline towards the former. I’ve been watching leaves fall since early last month, after all, but now – after a weekend spent taking a chilly boat ride down the canal, stocking the freezer with blackberries and elderberries, and setting hops to dry in the shed – it truly feels like autumn is here in southern England. Luckily, I had just the right book in hand to read over the last couple of weeks as I’ve been settling into our new place, Autumn: An anthology for the changing seasons.

This is the third of four seasonal volumes issued this year by the UK’s Wildlife Trusts, in partnership with London-based publisher Elliott & Thompson and edited by Melissa Harrison (see also my review of Summer). The format of all the books is roughly the same: pieces range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (poems by Shelley, Tennyson and Yeats) to recent nature writers (an excerpt from Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk; new work from Amy Liptrot and John Lewis-Stempel). Perhaps half the content has been contributed by talented amateurs, about 10 of them repeats from the first volumes.

This is the third of four seasonal volumes issued this year by the UK’s Wildlife Trusts, in partnership with London-based publisher Elliott & Thompson and edited by Melissa Harrison (see also my review of Summer). The format of all the books is roughly the same: pieces range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (poems by Shelley, Tennyson and Yeats) to recent nature writers (an excerpt from Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk; new work from Amy Liptrot and John Lewis-Stempel). Perhaps half the content has been contributed by talented amateurs, about 10 of them repeats from the first volumes.

This collection was slightly less memorable for me than Summer. A few pieces seem like school assignments, overly reliant on clichés of blackberry picking and crunching leaves underfoot. The best ones don’t attempt too much; they zero in on one species or experience and give a complete, self-contained story rather than general musings. A few stand-outs in this respect are Jo Cartnell chancing upon bank voles, Julian Jones on his obsession with eels, Laurence Arnold telling of his reptile surveying at London Wetland Center, and Lucy McRobert having a magic moment with dolphins off the Scilly Isles. I also enjoyed Kate Blincoe’s account of foraging for giant puffball mushrooms and Janet Willoner on pressing apples into juice – I’m looking forward to watching this at our town’s Apple Day in October.

I think all the contemporary writers would agree that you don’t have to live or go somewhere ‘special’ to commune with nature; there are marvels everywhere, even on your own tiny patch, if you will just go out and find them. For instance, South London seems an unlikely place for wildlife encounters, yet Will Harper-Penrose meets up with one of the country’s most strikingly exotic species (an introduced one), the ring-necked parakeet. Jane Adams comes across a persistent gang of wood mice in her very own attic, while Daphne Pleace spots red deer stags from the safety of her motorhome when on vacation in northwest Scotland.

A Japanese maple near the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Photo by Chris Foster.

Remarkably, the book’s disparate pieces together manage to convey a loose chronological progression, from the final days of lingering summer to the gradual onset of winter. Here’s Annie Worsley’s lovely portrayal of autumn’s approach: “In the woodlands the first trees to betray summer are silver birches: splashes of yellow dapple their fine, shimmering greenery. Here and there, long wavering larch tresses begin to change from deep green to orange and ochre.” At the other end of the autumnal continuum, David Gwilym Anthony’s somber climate change poem, “Warming,” provides a perfect close to the anthology: “These days I’ll take what Nature sends / to hoard for dour December: / a glow of warmth as autumn ends.”

A few more favorite lines:

- “Dusk, when the edges of all things blur. A time of mauve and moonlight, of shapeshiftings and stirrings, of magic.” (Alexi Francis)

- “Go down the village street on a late September afternoon and the warm burnt smell of jam-making oozes out of open cottage doors.” (Clare Leighton, 1933)

- “There are miniature Serengetis like this under most logs, if you take the time to look.” (Ryan Clark)

- “Ah, the full autumn Bisto bouquet comes powering to the nose: mouldering leaves, decaying mushrooms, rusting earth.” (John Lewis-Stempel)

My favorite essay of all, though, is by Jon Dunn: playful yet ultimately elegiac, it’s about returning to his croft on a remote Shetland island to find that an otter has been picking off his chickens.

All Saint’s Church in Woolstone, Oxfordshire. Photo by Chris Foster.

Like Summer, this gives a good sense of autumn as a whole, including its metaphorical associations. As Harrison puts it in her introduction, autumn “makes tangible a suite of emotions – wistfulness, nostalgia, a comfortable kind of melancholy – that are, at other times of the year, just out of reach.” It’s been my favorite season since childhood, probably because it combines the start of the school year, my birthday, and American holidays like Halloween and Thanksgiving. Whatever your own experience of autumn – whether it’s a much loved season or not; even if you call it “fall” instead – I can highly recommend this anthology’s chorus of voices old and new. There’s no better way for a book lover to usher in the season.

With thanks to Jennie Condell at Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

My rating:

The book proper opens with a visit to

The book proper opens with a visit to

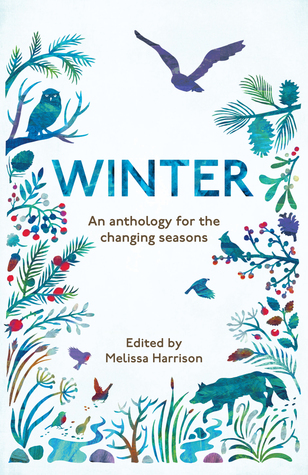

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.

The format in all the books is roughly the same: they’re composed of short pieces that range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (Adam Bede and Far from the Madding Crowd) to recent nature books (Mark Cocker’s

The format in all the books is roughly the same: they’re composed of short pieces that range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (Adam Bede and Far from the Madding Crowd) to recent nature books (Mark Cocker’s