Poetry Month Reviews & Interview: Amy Gerstler, Richard Scott, Etc.

April is National Poetry Month in the USA, and I was delighted to have several of my reviews plus an interview featured in a special poetry issue of Shelf Awareness on Friday. I’ve also recently read Richard Scott’s second collection.

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s razor-sharp third collection bears witness to the devastation of Gaza.

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Tonally, anger and grief alternate, while alliteration and slant rhymes (sweat/sweet) create entrancing rhythms. In “Before Gaza, a Fall” and “My Tongue Is Tied Up Today,” staccato phrasing and spaced-out stanzas leave room for the unspeakable. The pièce de résistance is “A Holy Land, Wasted” (co-written with Huda Fakhreddine), which situates T.S. Eliot’s existential ruin in Palestine. Almallah contrasts Gaza then and now via childhood memories and adult experiences at checkpoints. His pastiche of “The Waste Land” starts off funny (“April is not that bad actually”) but quickly darkens, scorning those who turn away from tragedy: “It’s not good/ for your nerves to watch/ all that news, the sights/ of dead children.” The wordplay dazzles again here: “to motes the world crumbles, shattered/ like these useless mots.”

For Almallah, who now lives in Philadelphia, Gaza is elusive, enduringly potent—and mourned. Sometimes earnest, sometimes jaded, Wrong Winds is a remarkable memorial. ![]()

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. “As Winter Sets In” delivers “every day/ a new face you can’t renounce or forsake.” “When I was a bird,” with its interspecies metamorphoses, introduces a more fantastical concept: “I once observed a scurry of squirrels,/ concealed in a hollow tree, wearing seventeenth/ century clothes. Alas, no one believes me.” Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen.

The collection contains five thematic slices. Part I spotlights women behaving badly (such as “Marigold,” about a wild friend; and “Mae West Sonnet,” in an hourglass shape); Part II focuses on music and sound. The third section veers from the inherited grief of “Schmaltz Alert” to the miniplay “Siren Island,” a tragicomic Shakespearean pastiche. Part IV spins elegies for lives and works cut short. The final subset includes a tongue-in-cheek account of pandemic lockdown activities (“The Cure”) and wry advice for coping (“Wound Care Instructions”).

Monologues and sonnets recur—the title’s “form” refers to poetic structures as much as to personal identity. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance. In the closing poem, “Night Herons,” nature puts life into perspective: “the whir of wings/ real or imagined/ blurs trivial things.”

This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques.

I also had the chance to interview Amy Gerstler, whose work was new to me. (I’ll certainly be reading more!) We chatted about animals, poetic forms and tone, Covid, the Los Angeles fires, and women behaving ‘badly’. ![]()

Little Mercy by Robin Walter

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

Many of Walter’s poems are as economical as haiku. “Lilies” entrances with its brief lines, alliteration, and sibilance: “Come/ dark, white/ petals// pull/close// —small fists// of night—.” A poem’s title often leads directly into the text: “Here” continues “the body, yes,/ sometimes// a river—little/ mercy.” Vocabulary and imagery reverberate, as the blessings of morning sunshine and a snow-covered meadow salve an unquiet soul (“how often, really, I want/ to end my life”).

Frequent dashes suggest affinity with Emily Dickinson, whose trademark themes of loss, nature, and loneliness are ubiquitous here, too. Vistas of the American West are a backdrop for pronghorn antelope, timothy grass, and especially the wrens nesting in Walter’s porch. Animals are also seen in peril sometimes: the family dog her father kicked in anger or a roadkilled fox she encounters. Despite the occasional fragility of the natural world, the speaker is “held by” it and granted “kinship” with its creatures. (How appropriate, she writes, that her mother named her for a bird.)

The collection skillfully illustrates how language arises from nature (“while picking raspberries/ yesterday I wanted to hold in my head// the delicious names of the things I saw/ so as to fold them into a poem later”—a lovely internal rhyme) and becomes a memorial: “Here, on earth,/ we honor our dead// by holding their names/ gentle in our hollow mouths—.”

This poised, place-saturated collection illuminates life’s little mercies. ![]()

The three reviews above are posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

That Broke into Shining Crystals by Richard Scott

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

It also mirrors his debut in that the book is in several discrete sections – like movements of a musical composition – and there are extended allusions to particular poets (there, Paul Verlaine and Walt Whitman; here, Andrew Marvell and Arthur Rimbaud). But there is one overall theme, and it’s a tough one: Scott’s boyhood grooming and molestation by a male adult, and how the trauma continues to affect him.

Part I contains 21 “Still Life” poems based on particular paintings, mostly by Dutch or French artists (see the Notes at the end for details). I preferred to read the poems blind so that I didn’t have the visual inspiration in my head. The imagery is startlingly erotic: the collection opens with “Like a foreskin being pulled back, the damask / reveals – pelvic bowl of pink-fringed shadow” (“Still Life with Rose”) and “Still Life with Bananas” starts “curved like dicks they sit – cosy in wicker – an orgy / of total yellowness – all plenty and arching – beyond / erect – a basketful of morning sex and sugar and sunlight”.

“O I should have been the / snail,” the poet laments; “Living phallus that can hide when threatened. But / I’m the oyster. … Cold jelly mess of a / boy shucked wide open.” The still life format allows him to freeze himself at particular moments of abuse or personal growth; “still” can refer to his passivity then as well as to his ongoing struggle with PTSD.

Part II, “Coy,” is what Scott calls a found poem or “vocabularyclept,” rearranging the words from Marvell’s 1681 “To His Coy Mistress” into 21 stanzas. The constraint means the phrases are not always grammatical, and the section as a whole is quite repetitive.

The title of the book (and of its final section) comes from Rimbaud and, according to the Notes, the 22 poems “all speak back to Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations but through the prism of various crystals and semi-precious stones – and their geological and healing properties.” My lack of familiarity with Rimbaud and his circle made me wonder if I was missing something, yet I thrilled to how visual the poems in this section were.

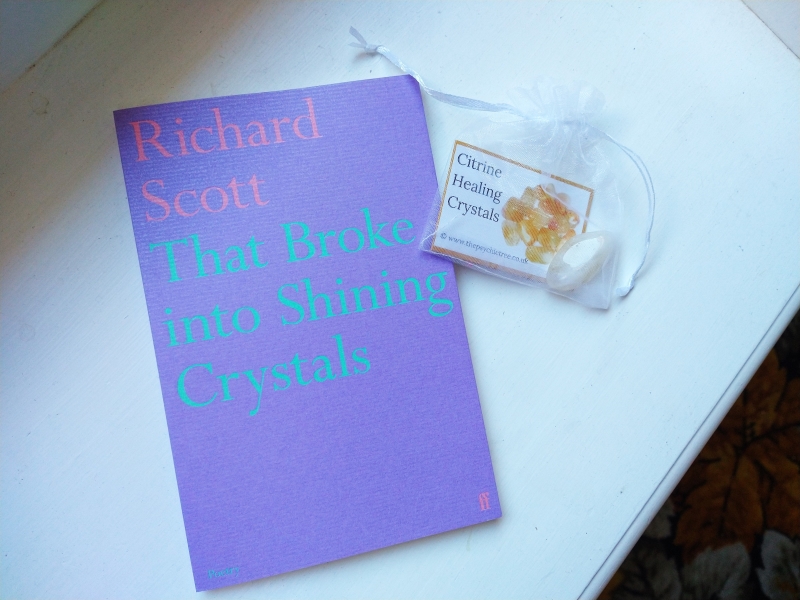

As with the Still Lifes, there’s an elevated vocabulary, forming a rich panoply of plants, creatures, stones, and colours. Alliteration features prominently throughout, as in “Citrine”: “O citrine – patron saint of the molested, sunny eliminator – crown us with your polychromatic glittering and awe-flecks. Offer abundance to those of us quarried. A boy is igneous.”

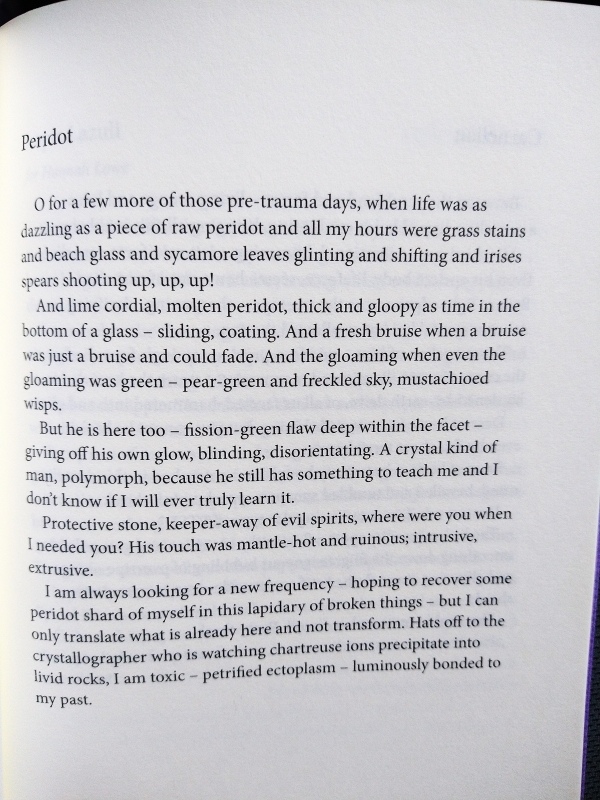

I’ve photographed “Peridot” (which was my mother’s birthstone) as an example of the before-and-after setup, the gorgeous language including alliteration, the rhetorical questioning, and the longing for lost innocence.

It was surprising to me that Scott refers to molestation and trauma so often by name, rather than being more elliptical – as poetry would allow. Though I admire this collection, my warmth towards it ebbed and flowed: I loved the first section; felt alienated by the second; and then found the third rather too much of a good thing. Perhaps encountering Part I or III as a chapbook would have been more effective. As it is, I didn’t feel the sections fully meshed, and the theme loses energy the more obsessively it’s repeated. Nonetheless, I’d recommend it to readers of Mark Doty, Andrew McMillan and Brandon Taylor. ![]()

Published today. With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. An abridged version of this review first appeared in my Instagram post of 11 April.

Read any good poetry recently?

Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?