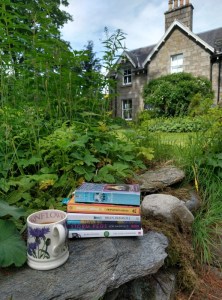

Three summers ago, we first explored the Outer Hebrides, moving south from Lewis through Harris to North Uist and Benbecula. It took longer than expected to make it back to the Western Isles. (It’s also taken longer than expected to write up a trip we took in late June. My excuse is we’ve been having work done in the house for a couple of weeks and it’s thrown off routines, plus we’re now away again on a short break.) We kept our word and completed the southern half of the chain this year, staying on South Uist and journeying via Eriskay to Barra and Vatersay. As last time, we combined public transport and car rental. Unlike last time, we had no major transport disasters. We took the train up to Edinburgh, where we rented a car and headed first of all to the edge of the Cairngorms. The village had little to offer apart from riverside scenery, so while my husband did beetle-collecting fieldwork nearby, I spent my time reading in the idyllic B&B grounds. Here the wildlife came to me: seven stags and a red squirrel! I’ve substituted in two of my relevant trip reads to my 20 Books of Summer roster.

20 Books of Summer, #4

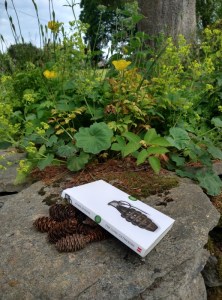

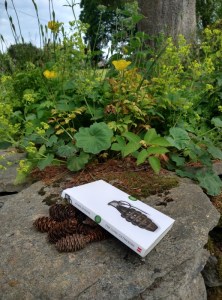

The Cone-Gatherers by Robin Jenkins (1955)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Then it was a several-hour drive to Oban to take our rescheduled ferry over to Lochboisdale in South Uist for the holiday proper to begin. With a six-night Airbnb stay booked in the home of a local woman, we relaxed into an unhurried pace of life. It’s more about the landscape than any particular indoor attractions here; during rainy spells we toured the excellent museum, tasted gin and rum at the North Uist (Downpour) and Benbecula (MacMillan Spirits) distilleries, took advantage of 5 for £1 books and CDs at the Benbecula thrift shop, and tried a couple of cafes, but for the most part we just made a few short excursions per day.

The croft where we stayed. Photo by Chris Foster.

Free souvenirs: rabbit bones and cow tooth

-

-

Honesty box with cakes

-

-

Photos by Chris Foster

-

We saw acres of machair (wildflower-rich fields), sand dunes undermined by an empire of rabbits, deserted beaches, and rare patches of woodland. We successfully staked out white-tailed sea eagles, red-throated divers, and a red-necked phalarope; watched cuckoos and short-eared owls (who are active in the daytime) as much as possible; and stared at every likely sea loch but failed to find an otter. Each evening we’d heat up a simple supper – pouches of curry and rice; ravioli with tomato sauce – using the microwave and hob. In quite a contrast to the heatwave-mired south of England, we had 12–16 degrees C (54–61 degrees F) most days, with light rain and high winds. The radiators and Rayburn (a big stove like an Aga) were on most of the time.

Weaving exhibit at South Uist Museum

SS Politician model (Whisky Galore)

20 Books of Summer, #5

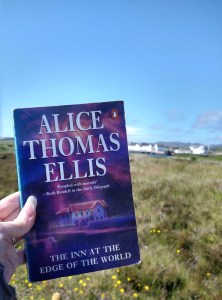

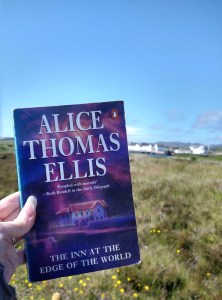

The Inn at the Edge of the World by Alice Thomas Ellis (1990)

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of Home Life), though this was light and enjoyable enough. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of Home Life), though this was light and enjoyable enough. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

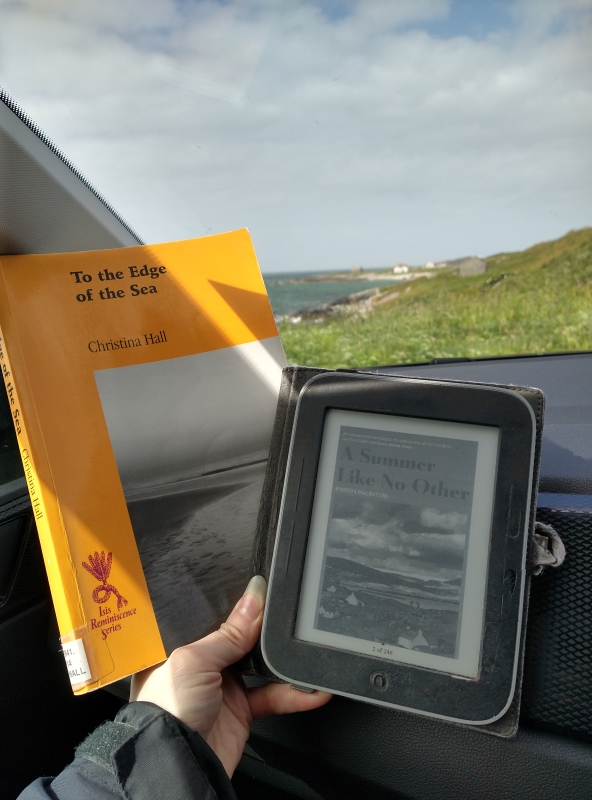

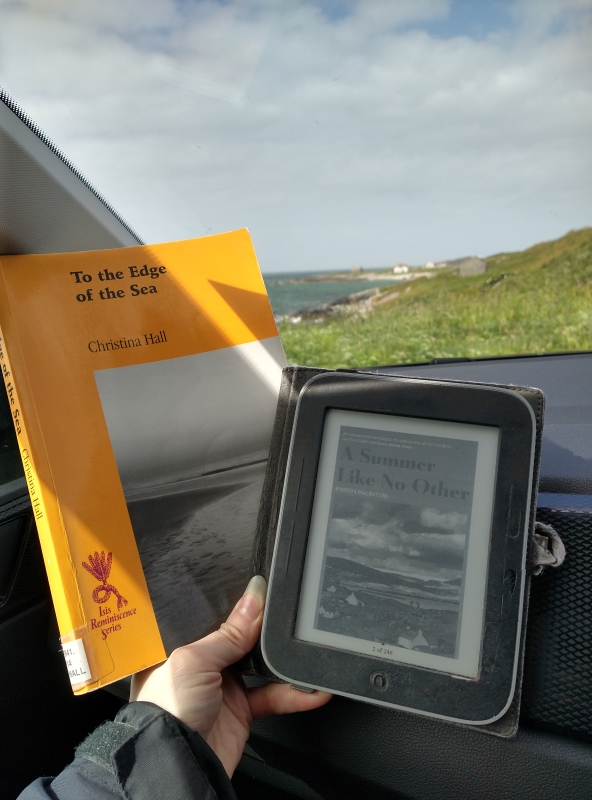

I was pleased that I managed to find two relevant hyperlocal reads. It was so neat to encounter the same place names out the car window and in my books:

To the Edge of the Sea: Schooldays of a Crofter’s Child by Christina Hall (1995)

Hall’s father inherited a South Uist croft and the family struggled so much financially that she was sent to live with her schoolteacher aunts on Benbecula and then Barra. Some things haven’t changed on the islands, such as the rabbits on the machair and the notoriously choppy ferry rides back to the mainland, where she attended a convent school at Fort William. There are some enjoyable pen portraits, such as of an Irish peddler. The most memorable incident was when she ran away from the aunts’ to attend a family wedding on Benbecula. The tone is pleasant, reminiscent of early Diana Athill and Doreen Tovey, but this isn’t one to pick up unless you have a particular interest in the places described. (Public library)

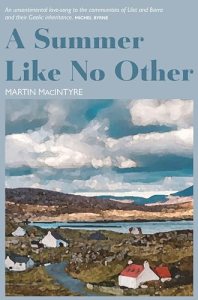

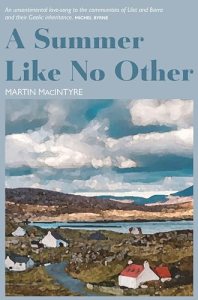

A Summer Like No Other by Martin MacIntyre (2018; 2025)

As World Cup fever ramps up in the summer of 1978, aimless 20-year-old Colin Quinn breaks from his university studies to shadow his uncle, Dr. Ruairidh Gillies, during his locum on South Uist. Between the home medical visits and recording folktales and songs by an eighty-something bard and several other members of the community, Colin gets to know almost everyone – but the person he knows the least well is himself. His involvement with the bard’s great-niece and her abusive husband will change the tenor of the summer for him, and have lasting consequences that only become clear decades later.

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

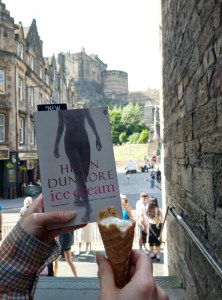

There’s Something about Mary

My husband would like it known that he was the clever clogs who spotted a theme to our trip: Mary.

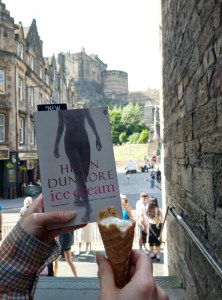

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

A piper statue at the Airbnb that continually frightened us on the stairs.

2) Our South Uist host was Mary MacInnes, a major mover and shaker in the local Gaelic-speaking community. (Her Alexa even obeyed Gaelic commands.) She is a retired head teacher of one of the schools and had various grandchildren popping in and out. Thanks to her heads-up, we had a unique cultural experience: a local arts venue’s lunchtime ceilidh of live music that was being filmed for BBC Scotland. Between her and others, we heard a lot of spoken Gaelic and got further into the mood by finding Julie Fowlis’s Gaelic-language albums online and playing them in our rental car. Each morning, Mary served us breakfast. We made the mistake of answering “Yes” to the question “D’ye take porridge?” on the first morning and had to slog through a stodgy bowl for five of the next six days. However, she also produced fresh-baked scones on two days and that made up for it. Triangular and baked in a cast-iron skillet, they tasted more like soda bread and were a perfect snack with jam.

3) The final full day of our trip was spent on Barra, a quick hop from South Uist. Whereas Lewis and Harris are staunchly Protestant, the southern islands are Catholic. We’d found a roadside shrine on South Uist, and on this late June day we devoted a couple of hours to climbing up Heaval, Barra’s highest hill as far as the statue of Mary, Star of the Sea. We were taken with this round, rugged island of secluded coves and beach-lounging cows; I can imagine going back to spend more time there. (I’d also like to see a bit more of Eriskay, from which our ferry departed and where the shipwreck that inspired Whisky Galore – one to read next time – took place.) Our hostel room overlooked the harbour where our ferry for the mainland was docked, which was handy as we had to be in the queue by 6:10 the next morning.

My additional reasonably local or otherwise relevant reading:

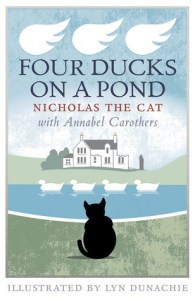

Four Ducks on a Pond: A Highland Memory by Nicholas the Cat with Annabel Carothers (2010)

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

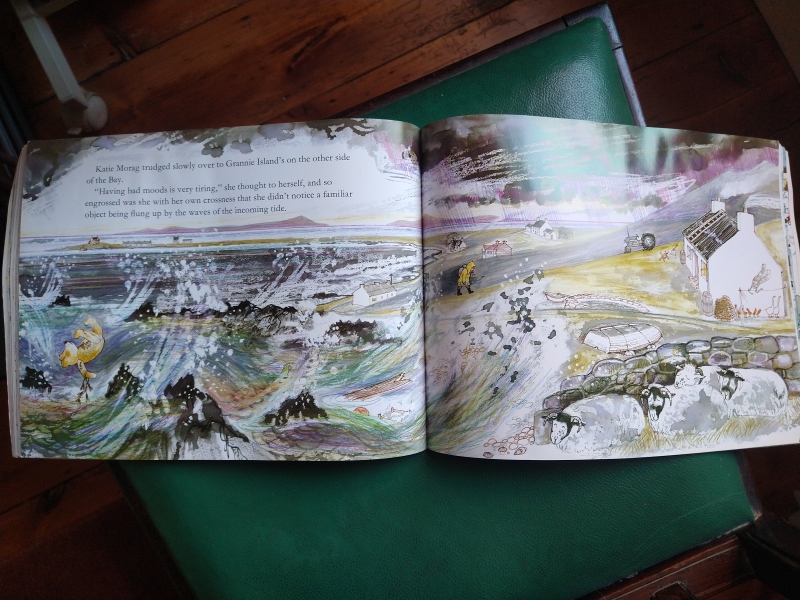

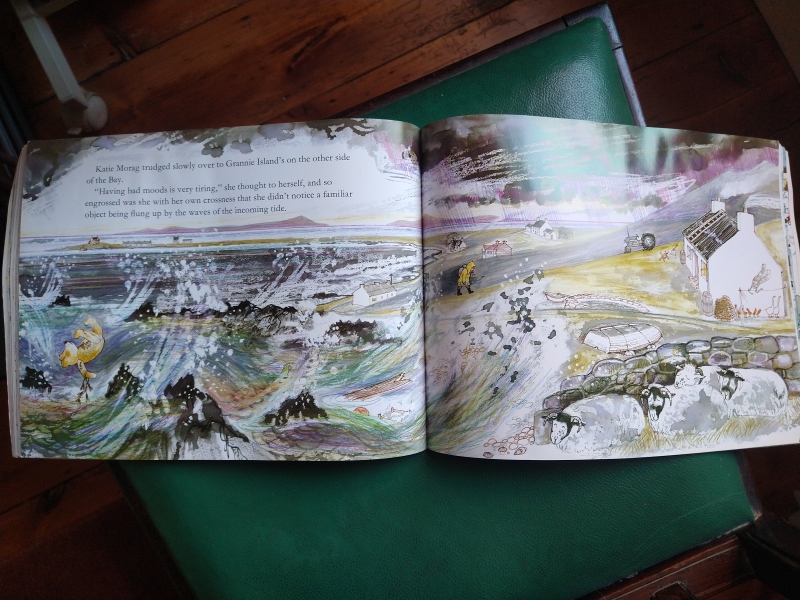

Katie Morag’s Island Stories by Mairi Hedderwick (1995)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

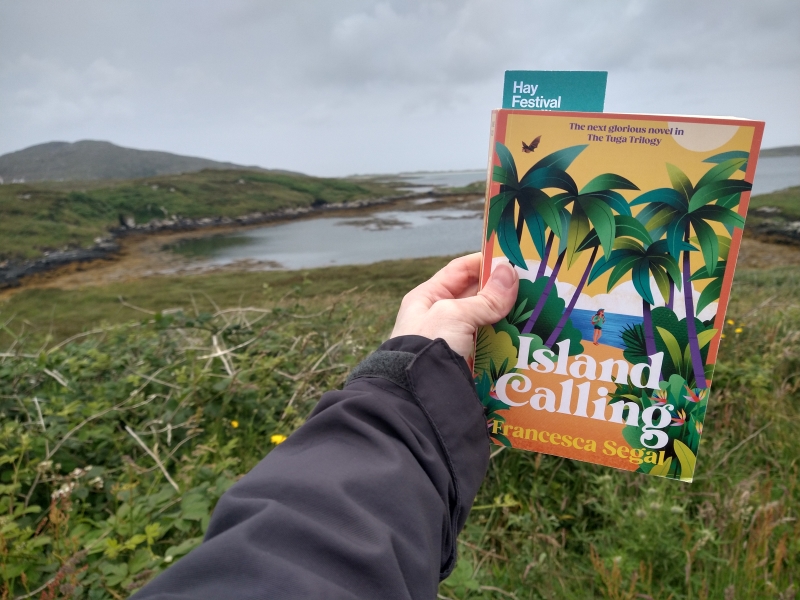

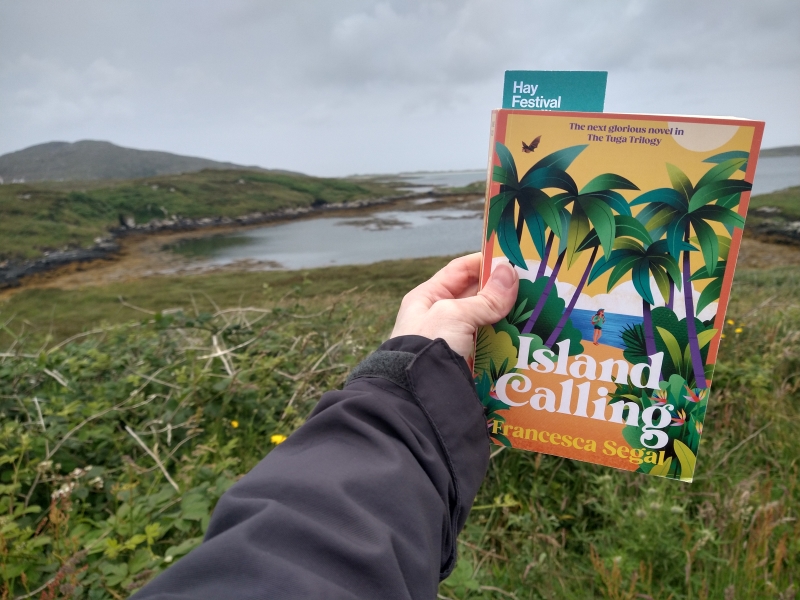

Island Calling by Francesca Segal (2025)

The sequel to Welcome to Glorious Tuga, which I reviewed for Shelf Awareness last year. Charlotte Walker is a tortoise researcher who becomes the default veterinarian on this remote South Atlantic island that combines a 1950s English ethos with a cosmopolitan heritage from sailors and settlers. In this volume, Charlotte resolves her troubled love triangle and cements her understanding of her father’s identity. But the main thing that happens is that her posh and entitled mother, Lucinda Compton-Neville, takes a break from her busy job as a QC to travel to the island and demand that Charlotte return to London with her. Motherhood is a strong theme throughout: Natalie Lindo, already a mother of four, has to decide what to do about a high-risk pregnancy; half-feral Annie Goss rejects her mother’s affection, and so on. Some of the characters are lovably quirky, but overall I find the cliché-laden series lackluster, a pointless and indulgent side-track and thus a real waste of talent by Segal (after The Innocents and Mother Ship, especially). If you enjoy romance novels or escapist beach reads, you might feel differently. But I won’t bother reading the third volume.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

I also made good progress on Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield, a memoir of life in Shetland – different islands with their own character, but still fitting the hardy Scottish spirit.

I’d finished my first 7 Books of Summer by the end of June, so I was on track as of then. (Reviews of two more coming up on Friday.) I’m in the middle of some designated reads, but it’ll be ages before I finish any. I’ll hope to review another batch by the end of July.

A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: In Fowler’s sixth novel, issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance and lead to tragedy in a seemingly idyllic North Carolina neighborhood. A Good Neighborhood is an up-to-the-minute story packed with complex issues including celebrity culture, casual racism, sexual exploitation, and environmental degradation. It is narrated in a first-person plural voice, much like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, this needs to be next on your to-read list. It is a book that will make you think, and a book that will make you angry; I recommend it to socially engaged readers and book clubs alike.

A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: In Fowler’s sixth novel, issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance and lead to tragedy in a seemingly idyllic North Carolina neighborhood. A Good Neighborhood is an up-to-the-minute story packed with complex issues including celebrity culture, casual racism, sexual exploitation, and environmental degradation. It is narrated in a first-person plural voice, much like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, this needs to be next on your to-read list. It is a book that will make you think, and a book that will make you angry; I recommend it to socially engaged readers and book clubs alike.

Pew by Catherine Lacey: Lacey’s third novel is a mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual. Pew’s narrator, homeless, mute and amnesiac, wakes up one Sunday in the middle of a church service, observing everything like an alien anthropologist. The stranger’s gender, race, and age are entirely unclear, so the Reverend suggests the name “Pew”. The drama over deciphering Pew’s identity plays out against the preparations for the enigmatic Forgiveness Festival and increasing unrest over racially motivated disappearances. Troubling but strangely compelling; recommended to fans of Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor. [U.S. publication pushed back to July 21st]

Pew by Catherine Lacey: Lacey’s third novel is a mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual. Pew’s narrator, homeless, mute and amnesiac, wakes up one Sunday in the middle of a church service, observing everything like an alien anthropologist. The stranger’s gender, race, and age are entirely unclear, so the Reverend suggests the name “Pew”. The drama over deciphering Pew’s identity plays out against the preparations for the enigmatic Forgiveness Festival and increasing unrest over racially motivated disappearances. Troubling but strangely compelling; recommended to fans of Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor. [U.S. publication pushed back to July 21st]

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones was determined to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She set out to make an empirical enquiry and discovered plenty of evidence in the scientific literature, but also attests to the personal benefits that nature has for her and explores the spiritual connection that many have found. Losing Eden is full of both common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Just as Silent Spring led to real societal change, let’s hope Jones’s work inspires steps in the right direction.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones was determined to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She set out to make an empirical enquiry and discovered plenty of evidence in the scientific literature, but also attests to the personal benefits that nature has for her and explores the spiritual connection that many have found. Losing Eden is full of both common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Just as Silent Spring led to real societal change, let’s hope Jones’s work inspires steps in the right direction.

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: While it ranges across the centuries, the novel always sticks close to the title location. Just as the louring rock is inescapable in the distance if you look out from the Edinburgh hills, there’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of the novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. The best 2020 novel I’ve read, memorable for its elegant, time-blending structure as well as its unrelenting course – and set against that perfect backdrop of an indifferent monolith.

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: While it ranges across the centuries, the novel always sticks close to the title location. Just as the louring rock is inescapable in the distance if you look out from the Edinburgh hills, there’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of the novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. The best 2020 novel I’ve read, memorable for its elegant, time-blending structure as well as its unrelenting course – and set against that perfect backdrop of an indifferent monolith.

I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas: A record of a demoralizing journey into extreme loneliness on a Scottish island, this offers slivers of hope that mystical connection with the natural world can restore a sense of self. In places the narrative is a litany of tragedies and bad news. The story’s cathartic potential relies on its audience’s willingness to stick with a book that can be – to be blunt –depressing. The writing often tends towards the poetic, but is occasionally marred by platitudes and New Age sentiments. As with Educated, it’s impossible not to marvel at all the author has survived. Admiring Calidas’s toughness, though, doesn’t preclude relief at reaching the final page. (Full review in May 29th issue.)

I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas: A record of a demoralizing journey into extreme loneliness on a Scottish island, this offers slivers of hope that mystical connection with the natural world can restore a sense of self. In places the narrative is a litany of tragedies and bad news. The story’s cathartic potential relies on its audience’s willingness to stick with a book that can be – to be blunt –depressing. The writing often tends towards the poetic, but is occasionally marred by platitudes and New Age sentiments. As with Educated, it’s impossible not to marvel at all the author has survived. Admiring Calidas’s toughness, though, doesn’t preclude relief at reaching the final page. (Full review in May 29th issue.)

We Swim to the Shark: Overcoming fear one fish at a time by Georgie Codd: Codd’s offbeat debut memoir chronicles her quest to conquer a phobia of sea creatures. Inspired by a friend’s experience of cognitive behavioral therapy to cure arachnophobia, she crafted a program of controlled exposure. She learned to scuba dive before a trip to New Zealand, returning via Thailand with an ultimate challenge in mind: her quarry was the whale shark, a creature even Jacques Cousteau only managed to sight twice. The book has a jolly, self-deprecating tone despite its exploration of danger and dread. A more directionless second half leads to diminished curiosity about whether that elusive whale shark will make an appearance. (Full review in a forthcoming issue.)

We Swim to the Shark: Overcoming fear one fish at a time by Georgie Codd: Codd’s offbeat debut memoir chronicles her quest to conquer a phobia of sea creatures. Inspired by a friend’s experience of cognitive behavioral therapy to cure arachnophobia, she crafted a program of controlled exposure. She learned to scuba dive before a trip to New Zealand, returning via Thailand with an ultimate challenge in mind: her quarry was the whale shark, a creature even Jacques Cousteau only managed to sight twice. The book has a jolly, self-deprecating tone despite its exploration of danger and dread. A more directionless second half leads to diminished curiosity about whether that elusive whale shark will make an appearance. (Full review in a forthcoming issue.)

Dottoressa: An American Doctor in Rome by Susan Levenstein: In the late 1970s, Levenstein moved from New York City to Rome with her Italian husband and set up a private medical practice catering to English-speaking expatriates. Her light-hearted yet trenchant memoir highlights the myriad contrasts between the United States and Italy revealed by their health care systems. Italy has a generous national health service, but it is perennially underfunded and plagued by corruption and inefficiency. The tone is conversational and even-handed. In the pandemic aftermath, though, Italian sloppiness and shortages no longer seem like harmless matters to shake one’s head over. (Full review coming up in June 19th issue.)

Dottoressa: An American Doctor in Rome by Susan Levenstein: In the late 1970s, Levenstein moved from New York City to Rome with her Italian husband and set up a private medical practice catering to English-speaking expatriates. Her light-hearted yet trenchant memoir highlights the myriad contrasts between the United States and Italy revealed by their health care systems. Italy has a generous national health service, but it is perennially underfunded and plagued by corruption and inefficiency. The tone is conversational and even-handed. In the pandemic aftermath, though, Italian sloppiness and shortages no longer seem like harmless matters to shake one’s head over. (Full review coming up in June 19th issue.)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)  1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)  I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)