More Books about Cats

Back in April I reviewed five books about cats, several of which proved to be a mite disappointing. I’m happy to report that in the meantime I have searched high and low and found some great books about cats that I would not hesitate to recommend to readers with even the slightest interest in our feline friends. I’ve got a book of trivia, a set of heart-warming autobiographical anecdotes, two books of poems, a sweet memoir, and – best of all – a wide-ranging new book that combines the science and cultural history of the domestic cat.

Fifty Nifty Cat Facts by J.M. Chapman and S.M. Davis

This one’s geared towards children, but I enjoyed the format: each page pairs a cute cat photo with a piece of trivia you might or might not have known. I learned a few neat things:

This one’s geared towards children, but I enjoyed the format: each page pairs a cute cat photo with a piece of trivia you might or might not have known. I learned a few neat things:

- a cat’s internal temperature is higher than ours (more like 101.5° F)

- cats have no sweet taste buds and have a dominant paw

- all calicos are female (orange spots being an X-linked genetic trait)

- cats could actually drink seawater – their kidneys are effective enough to process the salt

- people who say they are allergic to cat fur are actually allergic to a protein in the saliva they use to wash themselves!

My rating:

Cat Stories by James Herriot

When I was a child my mother and I loved Herriot’s memoirs of life as a primarily large-animal veterinarian in Yorkshire. One story from this volume – the final, Christmas-themed one – is familiar from a picture book we brought out around the holidays. The rest are all drawn from the memoirs, though, so the fact that I don’t remember them must be a function of time; it could be as many as 22 years since I last picked up a Herriot book! In any case, these are charming tales about gentle medical mysteries and even the most aloof of stray cats becoming devoted pets. I especially liked “Alfred: The Sweet-Shop Cat” and “Oscar: The Socialite Cat,” about two endearing creatures known around the village. I also appreciated Herriot’s observation that “cats are connoisseurs of comfort.” With cute watercolor illustrations, this little book would make a great gift for any cat lover.

When I was a child my mother and I loved Herriot’s memoirs of life as a primarily large-animal veterinarian in Yorkshire. One story from this volume – the final, Christmas-themed one – is familiar from a picture book we brought out around the holidays. The rest are all drawn from the memoirs, though, so the fact that I don’t remember them must be a function of time; it could be as many as 22 years since I last picked up a Herriot book! In any case, these are charming tales about gentle medical mysteries and even the most aloof of stray cats becoming devoted pets. I especially liked “Alfred: The Sweet-Shop Cat” and “Oscar: The Socialite Cat,” about two endearing creatures known around the village. I also appreciated Herriot’s observation that “cats are connoisseurs of comfort.” With cute watercolor illustrations, this little book would make a great gift for any cat lover.

My rating:

I Could Pee on This: And Other Poems by Cats by Francesco Marciuliano

Cat owners must own a copy for the coffee table. That’s just not negotiable. You will recognize so many of the behaviors and attitudes mentioned here. This is a humor book rather than a poetry collection, so the quality of the poems (all from the point-of-view of a cat) is kind of neither here nor there. Even so, Chapter 1 is a lot better than the other three and contains most of the purely hilarious verses, like “I Lick Your Nose” and “Closed Door.” Favorite lines included “I trip you when you walk down the stairs / So you know I’m always near” and “I said I could sit on your lap forever / Don’t you even think of trying to get up / Well, you should have gone to the bathroom beforehand”. “Sushi” is a perfect haiku with a kicker of a last line: “Did you really think / That you could hide fish in rice? / Oh, the green paste burns!”

Cat owners must own a copy for the coffee table. That’s just not negotiable. You will recognize so many of the behaviors and attitudes mentioned here. This is a humor book rather than a poetry collection, so the quality of the poems (all from the point-of-view of a cat) is kind of neither here nor there. Even so, Chapter 1 is a lot better than the other three and contains most of the purely hilarious verses, like “I Lick Your Nose” and “Closed Door.” Favorite lines included “I trip you when you walk down the stairs / So you know I’m always near” and “I said I could sit on your lap forever / Don’t you even think of trying to get up / Well, you should have gone to the bathroom beforehand”. “Sushi” is a perfect haiku with a kicker of a last line: “Did you really think / That you could hide fish in rice? / Oh, the green paste burns!”

My rating:

Well-Versed Cats by Lance Percival

A cute set of poems, most of them describing different breeds of domestic cats and a few of the big cats. There are a lot of puns and jokes along with the end rhymes, making these akin to limericks in tone if not in form. My favorite was “Skimpy the Stray?” – about a wily cat who wanders the neighborhood eliciting sympathetic snacks from various cat lovers. “The routine still goes on, so I mustn’t be too catty, / But she ought to change her name from ‘Skimpy’ into ‘Fatty’.” Our cat had a habit of stealing neighbor kitties’ food and a history of “going visiting,” as the shelter we adopted him from put it, so this particular poem rang all too true. The illustrations (by Lalla Ward, wife of Richard Dawkins) are also great fun.

A cute set of poems, most of them describing different breeds of domestic cats and a few of the big cats. There are a lot of puns and jokes along with the end rhymes, making these akin to limericks in tone if not in form. My favorite was “Skimpy the Stray?” – about a wily cat who wanders the neighborhood eliciting sympathetic snacks from various cat lovers. “The routine still goes on, so I mustn’t be too catty, / But she ought to change her name from ‘Skimpy’ into ‘Fatty’.” Our cat had a habit of stealing neighbor kitties’ food and a history of “going visiting,” as the shelter we adopted him from put it, so this particular poem rang all too true. The illustrations (by Lalla Ward, wife of Richard Dawkins) are also great fun.

My rating:

Raining Cats and Donkeys by Doreen Tovey

Originally from 1967, this lighthearted memoir tells of Tovey’s life in a Somerset village with her husband Charles, two demanding Siamese cats named Solomon and Sheba, and Annabel the donkey. “Nobody misses anything in our village,” Tovey remarks, and along with her charming anecdotes about her pets there are plenty of amusing encounters with the human locals too. In my favorite chapter, Annabel is taken off to mate with a Shetland pony and Solomon has a tussle with a hare. I can recommend this to fans of animal books by Gerald Durrell and Jon Katz. Tovey wrote a whole series of books about her various Siamese cats and life in a 250-year-old cottage. I found a copy of Cats in the Belfry on my visit to Cambridge and will probably read it over Christmas for a cozy treat.

Originally from 1967, this lighthearted memoir tells of Tovey’s life in a Somerset village with her husband Charles, two demanding Siamese cats named Solomon and Sheba, and Annabel the donkey. “Nobody misses anything in our village,” Tovey remarks, and along with her charming anecdotes about her pets there are plenty of amusing encounters with the human locals too. In my favorite chapter, Annabel is taken off to mate with a Shetland pony and Solomon has a tussle with a hare. I can recommend this to fans of animal books by Gerald Durrell and Jon Katz. Tovey wrote a whole series of books about her various Siamese cats and life in a 250-year-old cottage. I found a copy of Cats in the Belfry on my visit to Cambridge and will probably read it over Christmas for a cozy treat.

My rating:

The Lion in the Living Room by Abigail Tucker

Now this is the amazing cat book I’d been looking for! It’s a fascinating interdisciplinary look at how the domestic cat has taken over the world – both literally and figuratively. A writer for Smithsonian magazine, Tucker writes engaging, accessible popular science. The closest comparison I can make, style-wise, is to Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, even though that has much heavier subject matter.

Now this is the amazing cat book I’d been looking for! It’s a fascinating interdisciplinary look at how the domestic cat has taken over the world – both literally and figuratively. A writer for Smithsonian magazine, Tucker writes engaging, accessible popular science. The closest comparison I can make, style-wise, is to Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, even though that has much heavier subject matter.

The book traces domestic cat evolution from the big cats of the La Brea tar pits to the modern day, explaining why cats are only built to eat flesh and retain the hunting instinct even though they rarely have to look further than their designated bowls for food nowadays. Alongside the science, though, is plenty of cultural history. You’ll learn about how cats have been an invasive species in many sensitive environments, and about the bizarre, Halloween-scary story of the Toxoplasma gondii parasite. You’ll meet the tender hearts who volunteer for trap, neuter and release campaigns to cut down on the euthanizing of strays at shelters; the enthusiasts who breed unusual varieties of cats and groom them for shows; and the oddballs who buy into the $58 billion pet industry’s novelty accessories.

The lion in my living room.

From the earliest domestication of animals to the cat meme-dominated Internet, Tucker – a cat lady herself, as frequent mentions of her ginger tom Cheeto attest – marvels at how cats have succeeded by endearing themselves to humans and adapting as if effortlessly to any habitat in which they find themselves. A must for cat lovers for sure, but I don’t think you even have to be a pet person to find this all-embracing book pretty enthralling.

My rating:

Up next: The Church Cat, an anthology from a recent charity shop haul; The Cat Who Came for Christmas by Cleveland Amory, Cat Sense by John Bradshaw, and Talk to the Tail by Tom Cox from the public library.

Whether you consider yourself a cat lover or not, do any of these books appeal?

Review: Seal Morning by Rowena Farre

Here’s an obscure nature classic for animal lovers who can’t get enough of Gerald Durrell and James Herriot. It was a bestseller and a critical success when first published in 1957, and the fact that it has been reprinted several times in the new millennium is testament to its enduring appeal. It’s the account of seven years Farre spent living in a primitive Scottish croft (no electricity or running water) with her Aunt Miriam, starting at age 10. Despite an abrupt beginning, a dearth of dialogue and slightly rushed storytelling, I found this very enjoyable.

Like the young Durrell, Farre kept a menagerie of wild and half-domesticated animals, including Cuthbert and Sara the gray squirrels, Rodney the rat, Hansel and Gretel the otters, and – the star of this memoir – Lora, a common seal pup. Other pets came and went, like an ill-tempered roe deer fawn, a family of song thrushes, and a pair of fierce wild cat kittens. Early chapters about the struggle to keep all these ravenous creatures fed and wrangled are full of humorous mishaps, like Cuthbert falling down a chimney into the porridge.

Like the young Durrell, Farre kept a menagerie of wild and half-domesticated animals, including Cuthbert and Sara the gray squirrels, Rodney the rat, Hansel and Gretel the otters, and – the star of this memoir – Lora, a common seal pup. Other pets came and went, like an ill-tempered roe deer fawn, a family of song thrushes, and a pair of fierce wild cat kittens. Early chapters about the struggle to keep all these ravenous creatures fed and wrangled are full of humorous mishaps, like Cuthbert falling down a chimney into the porridge.

Farre acquired Lora on a trip to Lewis. Like dogs, seal pups are very loyal and attached. Farre fed Lora a bottle on her lap and let her sleep at the foot of the bed. Lora was also strikingly intelligent: she recognized 35 words, collected the mail from the postman, unpacked groceries and had an aptitude for music, including playing the mouth organ and xylophone and ‘singing’ along to piano accompaniment. She and the otters, along with Ben the dog, loved to frolic in the water and slide down snowy hills in the winter.

Besides capturing animal antics, what Farre does best in this book is to evoke the extreme isolation of their living situation. Aunt Miriam had saved up £75 a year for them to live off, but also painted designs on wooden bowls for extra cash. The regular summer routine of storing up food was not about passing the time but survival. Near-catastrophes, like getting lost in a mountain mist or the goats raiding Lora’s food supply, showed how precarious life could be. There was little to do on winter days, and only five or six hours of daylight anyway;

“Another hour in the croft and I would have had a nervous breakdown,” said Aunt Miriam. Life up here got you like that sometimes.

Really there are very few adults these days who possess the mental and emotional self-sufficiency necessary for leading satisfactory existences in these remote parts.

A life with animals is bound to involve some sadness. One pet gets picked off by a peregrine; another is injured in a trap and has to be put down. Ben’s fate is particularly sad. Lora’s, by contrast, is just mysterious: after seven years at the croft, she simply disappeared. Farre never learned what became of her.

At age 17, Farre had to decide how to make her own way in life. She took solo camping trips to contemplate her future, doing some informal seal research on Shetland and Iceland. Especially after Aunt Miriam met a Canadian man on an extended trip to visit friends in Berkshire and got engaged, it was clear that their crofting life together was soon to end. Farre hints at what happened next for her: she would go on to travel with British gypsies and journey to the Himalayas, subjects for two further autobiographies. The book ends on a melancholy note as Farre returns to the croft five years later and finds it no better than a ruin.

Farre died relatively young, aged 57 in 1979. Alas, an afterword by Maurice Fleming introduces an element of doubt about the writer and the strict veracity of her memoir. For one thing, Rowena Farre wasn’t her real name. “Piecing Daphne Lois Macready’s life together is like laying out a jigsaw from which some bits are missing and others faded,” Fleming writes. We know she was born in India to an Army officer and the family moved around the Far East for a number of years. However, Farre does not account for her formal schooling, and no evidence of the croft has ever been found. In other words, we don’t know how much is true.

Does this matter? It doesn’t detract from my enjoyment of this lively animal-themed memoir (after all, Herriot also did plenty of fictionalizing), but it does make me wonder whether some of Lora’s feats might be made up. Are seals really as intelligent and personable as she makes them out to be? I was left feeling slightly uneasy, and wanting to do more research about both Farre and seals to figure out what’s what. Still, this is a wonderfully cozy read to pick up by a fire this autumn or winter.

With thanks to the publisher, Birlinn, for the free copy.

My rating:

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep.

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep.

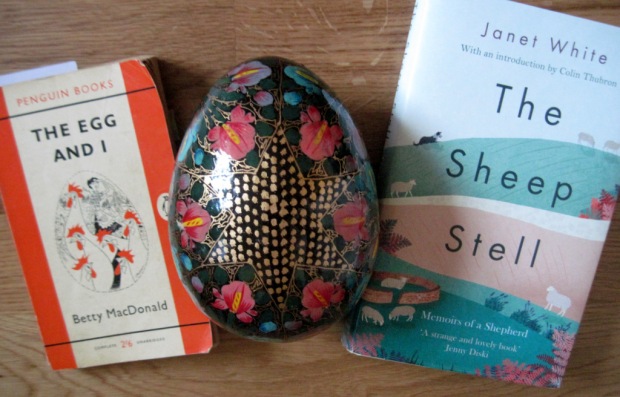

First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)

First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)  Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.

Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.

#4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

#4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

I’m reviewing this reissued memoir for the TLS. It’s a delightful story of finding contentment in the countryside, whether on her own or with family. White, now in her eighties, has been a shepherd for six decades in the British Isles and in New Zealand. While there’s some darker material here about being stalked by a spurned suitor, the tone is mostly lighthearted. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s enjoyed books by Gerald Durrell, James Herriot and Doreen Tovey.

I’m reviewing this reissued memoir for the TLS. It’s a delightful story of finding contentment in the countryside, whether on her own or with family. White, now in her eighties, has been a shepherd for six decades in the British Isles and in New Zealand. While there’s some darker material here about being stalked by a spurned suitor, the tone is mostly lighthearted. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s enjoyed books by Gerald Durrell, James Herriot and Doreen Tovey. Mrs. Creasy disappears one Monday in June 1976, and ten-year-old Grace Bennett and her friend Tilly are determined to figure out what happened. I have a weakness for precocious child detectives (from Harriet the Spy to Flavia de Luce), so I enjoyed Grace’s first-person sections, but it always feels like cheating to me when an author realizes they can’t reveal everything from a child’s perspective so add in third-person narration and flashbacks. These fill in the various neighbors’ sad stories and tell of a rather shocking act of vigilante justice they together undertook nine years ago.

Mrs. Creasy disappears one Monday in June 1976, and ten-year-old Grace Bennett and her friend Tilly are determined to figure out what happened. I have a weakness for precocious child detectives (from Harriet the Spy to Flavia de Luce), so I enjoyed Grace’s first-person sections, but it always feels like cheating to me when an author realizes they can’t reveal everything from a child’s perspective so add in third-person narration and flashbacks. These fill in the various neighbors’ sad stories and tell of a rather shocking act of vigilante justice they together undertook nine years ago.

My first collection from the prolific Pulitzer winner. Some of the poems are built around self-interrogation, with a question and answer format; several reflect on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first and last poems are both entitled “Vita Nova,” while another in the middle is called “The New Life.” I enjoyed the language of spring in the first “Vita Nova” and in “The Nest,” but I was unconvinced by much of what Glück writes about love and self-knowledge, some of it very clichéd indeed, e.g. “I found the years of the climb upward / difficult, filled with anxiety” (from “Descent to the Valley”) and “My life took me many places, / many of them very dark” (from “The Mystery”).

My first collection from the prolific Pulitzer winner. Some of the poems are built around self-interrogation, with a question and answer format; several reflect on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first and last poems are both entitled “Vita Nova,” while another in the middle is called “The New Life.” I enjoyed the language of spring in the first “Vita Nova” and in “The Nest,” but I was unconvinced by much of what Glück writes about love and self-knowledge, some of it very clichéd indeed, e.g. “I found the years of the climb upward / difficult, filled with anxiety” (from “Descent to the Valley”) and “My life took me many places, / many of them very dark” (from “The Mystery”).