Finishing 20 Books of Summer: The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green

The final choice for my colour-themed 20 Books of Summer, a terrific essay collection about the best and worst of the modern human experience, also happened to be the only one where the colour was part of the author’s name rather than the book’s title. I also have a bonus rainbow-covered read and a look back at the highlights of my summer reading.

The Anthropocene Reviewed: Essays on a Human-Centered Planet by John Green (2021)

(20 Books of Summer, #20) How Have You Enjoyed the Anthropocene So Far? That’s the literal translation of the book’s German title, but also a tidy summary of its approach. John Green is not only a YA author but also a new media star – he and his brother Hank are popular vlogging co-hosts, and this book arose from a podcast of the same name. Some of the essays first appeared on his various video projects, too. In about 5–10 pages, he takes a phenomenon experienced in the modern age, whether miraculous (sunsets, the Lascaux cave paintings, favourite films or songs), regrettable (Staph infections, CNN, our obsession with grass lawns), or just plain weird, and riffs on it, exploring its backstory, cultural manifestations and personal resonance.

Indeed, the essays reveal a lot about Green himself. I didn’t know of his struggles with anxiety and depression. “Harvey,” one of the standout essays, is about a breakdown he had in his early twenties when living in Chicago and working for Booklist magazine. His boss told him to take as much time as he needed, and urged him to watch Harvey, the Jimmy Stewart film about a man with an imaginary friend that happens to be a six-foot rabbit. It was the perfect prescription. In “Auld Lang Syne,” Green toggles between the history of the song and a friendship from his own old times, with an author and mentor who has since died. “Googling Strangers” prides itself on a very 21st-century skill by which he discovers that a critically injured boy from his time as a student chaplain at a children’s hospital lived to adulthood.

Green is well aware of the state of things: “Humans are already an ecological catastrophe … for many forms of life, humanity is the apocalypse.” He plays up the contradictions in everyday objects: air-conditioning is an environmental disaster, yet makes everyday life tolerable in vast swathes of the USA; Canada geese are still, to many, a symbol of wildness, but are almost frighteningly ubiquitous – one of the winners in the species roulette we’ve initiated. And although he’s clued in, he knows that in many respects he’s still living as if the world isn’t falling apart. “In the daily grind of a human life, there’s a lawn to mow, soccer practices to drive to, a mortgage to pay. And so I go on living the way I feel like people always have.” A sentiment that rings true for many of us: despite the background dread about where everything is headed, we just have to get on with our day-to-day obligations, right?

Although he’s from Indianapolis, a not particularly well regarded city of the Midwest, Green is far from the conservative, insular stereotype of that region. There are pockets of liberal, hipster culture all across the Midwest, in fact, and while he does joke about Indy in the vein of “well, you’ve gotta live somewhere,” it’s clear that he’s come to love the place – enough to set climactic scenes from two of his novels there. However, he’s also cosmopolitan enough – he’s a Liverpool FC fan, and one essay is set on a trip to Iceland – to be able to see America’s faults (which, to an extent, are shared by many Western countries) of greed and militarism and gluttony and more.

In any book like this, one might quibble with the particular items selected. I mostly skipped over the handful of pieces on sports and video games, for instance. But even when the phenomena were completely unknown to me, I was still tickled by Green’s take. For example, here he is rhapsodizing on Diet Dr Pepper: “Look at what humans can do! They can make ice-cold, sugary-sweet, zero-calorie soda that tastes like everything and also like nothing.” He veers between the funny and the heartfelt: “I want to be earnest, even if it’s embarrassing.”

Each essay closes with a star rating. What value does a numerical assessment have when he’s making such apples-and-oranges comparisons (a sporting performance vs. sycamore trees vs. hot dog eating contests)? Not all that much. (Of course, some might make that very argument about rating books, but I persist!) At first I thought the setup was a silly gimmick, but since reviewing anything and everything on Amazon/TripAdvisor/wherever is as much a characteristic of our era as everything he’s writing about, why not? Calamities get 1–1.5 stars, things that seemed good but have turned out to be mixed blessings might get 2–3 stars, and whatever he unabashedly loves gets 4.5–5 stars.

As Green astutely remarks, “when people write reviews, they are really writing a kind of memoir—here’s what my experience was.” So, because I found a lot that resonated with me and a lot that made me laugh, and admired his openness on mental health à la Matt Haig, but also found the choices random such that a few essays didn’t interest me and the whole doesn’t necessarily build a cohesive argument, I give The Anthropocene Reviewed four stars. I’d only ever read The Fault in Our Stars, one of the first YA books I loved, so this was a good reminder to try more of Green’s fiction soon.

(Public library)

Initially, I thought I might struggle to find 20 appealing colour-associated books, so I gave myself latitude to include books with different coloured covers. As it happens, I didn’t have to resort to choosing by cover, but I’ve thrown in this rainbow cover as an extra.

Songs in Ursa Major by Emma Brodie (2021)

A Daisy Jones and the Six wannabe for sure, and a fun enough summer read even though the writing doesn’t nearly live up to Reid’s. Set largely between 1969 and 1971, the novel stars Jane Quinn, who lives on New England’s Bayleen Island with her aunt, grandmother and cousin – her aspiring singer mother having disappeared when Jane was nine. Nursing and bartending keep Jane going while she tries to make her name with her band, the Breakers. Aunt Grace, also a nurse, cares for local folk rocker Jesse Reid during his convalescence from a motorcycle accident. He then invites the Breakers to open for him on his tour and he and Jane embark on a turbulent affair. After Jane splits from both Jesse and the Breakers, she shrugs off her sexist producer and pours her soul into landmark album Songs in Ursa Major. (I got the Sufjan Stevens song “Ursa Major” in my head nearly every time I picked this up.)

A Daisy Jones and the Six wannabe for sure, and a fun enough summer read even though the writing doesn’t nearly live up to Reid’s. Set largely between 1969 and 1971, the novel stars Jane Quinn, who lives on New England’s Bayleen Island with her aunt, grandmother and cousin – her aspiring singer mother having disappeared when Jane was nine. Nursing and bartending keep Jane going while she tries to make her name with her band, the Breakers. Aunt Grace, also a nurse, cares for local folk rocker Jesse Reid during his convalescence from a motorcycle accident. He then invites the Breakers to open for him on his tour and he and Jane embark on a turbulent affair. After Jane splits from both Jesse and the Breakers, she shrugs off her sexist producer and pours her soul into landmark album Songs in Ursa Major. (I got the Sufjan Stevens song “Ursa Major” in my head nearly every time I picked this up.)

There are some soap opera twists and turns to the plot, and I would say the novel is at least 100 pages too long, with an unnecessary interlude on a Greek island. Everyone loves a good sex, drugs and rock ’n roll tale, but here the sex scenes were kind of cringey, and the lyrics and descriptions of musical styles seemed laboured. Also, I thought from the beginning that the novel could use the intimacy of a first-person narrator, but late on realized it had to be in the third person to conceal a secret of Jane’s – which ended up feeling like a trick. There are also a few potential anachronisms (e.g. I found myself googling “how much did a pitcher of beer cost in 1969?”) that took me out of the period. Brodie is a debut novelist who has worked in book publishing in the USA for a decade. Her Instagram has a photo of her reading Daisy Jones and the Six in March 2019! That and the shout-out to Mandy Moore, of all the musical inspirations, in her acknowledgments, had me seriously doubting her bona fides to write this story. Maybe take it as a beach read if you aren’t too picky.

(Twitter giveaway win)

Looking back, my favourite read from this project was Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon, closely followed by the novels Under the Blue by Oana Aristide and Ruby by Ann Hood, the essay collection The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green (above), the travel book The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, and the memoirs Darkness Visible by William Styron and Direct Red by Gabriel Weston. A varied and mostly great selection, all told! I read six books from the library and the rest from my shelves. Maybe next year I’ll not pick a theme but allow myself completely free choice – so long as they’re all books I own.

What was the highlight of your summer reading?

Book Serendipity, May to June 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20‒30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Sufjan Stevens songs are mentioned in What Is a Dog? by Chloe Shaw and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- There’s a character with two different coloured eyes in The Mothers by Brit Bennett and Painting Time by Maylis de Kerangal.

- A description of a bathroom full of moisturizers and other ladylike products in The Mothers by Brit Bennett and The Interior Silence by Sarah Sands.

- A description of having to saw a piece of furniture in half to get it in or out of a room in A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- The main character is named Esther Greenwood in the Charlotte Perkins Gilman short story “The Unnatural Mother” in the anthology Close Company and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Indeed, it seems Plath may have taken her protagonist’s name from the 1916 story. What a find!

- Reading two memoirs of being in a coma for weeks and on a ventilator, with a letter or letters written by the hospital staff: Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen and Coma by Zara Slattery.

- Reading two memoirs that mention being in hospital in Brighton: Coma by Zara Slattery and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Reading two books with a character named Tam(b)lyn: My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier and Coma by Zara Slattery.

- A character says that they don’t miss a person who’s died so much as they miss the chance to have gotten to know them in Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour and In by Will McPhail.

- A man finds used condoms among his late father’s things in The Invention of Solitude by Paul Auster and Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour.

- An absent husband named David in Open House by Elizabeth Berg and Ruby by Ann Hood.

- The murder of Thomas à Becket featured in Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot (read in April) and Heavy Time by Sonia Overall (read in June).

- Adrienne Rich is quoted in (M)otherhood by Pragya Agarwal and Heavy Time by Sonia Overall.

- A brother named Danny in Immediate Family by Ashley Nelson Levy and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler.

- The male lead is a carpenter in Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler.

- An overbearing, argumentative mother who is a notably bad driver in Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny and Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott.

- That dumb 1989 movie Look Who’s Talking is mentioned in (M)otherhood by Pragya Agarwal and Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny.

- In the same evening, I started two novels that open in 1983, the year of my birth: The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris and Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid.

- “Autistic” is used as an unfortunate metaphor for uncontrollable or fearful behavior in Open House by Elizabeth Berg and Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott (from 2000 and 2002, so they’re dated references rather than mean-spirited ones).

A secondary character mentions a bad experience in a primary school mathematics class as being formative to their later life in Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler (at least, I think it was in the Tyler; I couldn’t find the incident when I went back to look for it. I hope Liz will set me straight!).

A secondary character mentions a bad experience in a primary school mathematics class as being formative to their later life in Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler (at least, I think it was in the Tyler; I couldn’t find the incident when I went back to look for it. I hope Liz will set me straight!).

- The panopticon and Foucault are referred to in Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead and I Live a Life Like Yours by Jan Grue. Specifically, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon is the one mentioned in the Shipstead, and Bentham appears in The Cape Doctor by E.J. Levy.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Six Degrees of Separation: From Fleishman Is in Trouble to Shotgun Lovesongs

I’ve not participated in Kate’s Six Degrees of Separation meme before, although I’d seen it around on other people’s blogs. I think all this time I’d misunderstood, assuming that you had to go from the start point to one particular end point. Instead, bloggers are given one book to start with and then have free rein to link it to six other books in whatever ways. Most of the fun is in seeing the different directions and destinations people choose. I am always drawing connections between books I read and noting coincidences (e.g., my occasional Book Serendipity posts), so this is a perfect meme for me! I’m very late in posting this month – for a while I was stuck on link #4 – but next month I’ll be right on it.

#1 Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner: I didn’t care for this debut novel about a crumbling marriage and upper-middle-class angst in contemporary New York City. A major plot point is the mother going missing, just like in Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple, a very pleasing epistolary novel I read in 2013.

#2 There’s also an absent Bernadette in Run by Ann Patchett (2007), which opens with a killer line: “Bernadette had been dead two weeks when her sisters showed up in Doyle’s living room asking for the statue back.” (Alas, I abandoned the novel after 80 pages; it has a lot of interesting elements, but they don’t seem to fit together in the same book.)

#2 There’s also an absent Bernadette in Run by Ann Patchett (2007), which opens with a killer line: “Bernadette had been dead two weeks when her sisters showed up in Doyle’s living room asking for the statue back.” (Alas, I abandoned the novel after 80 pages; it has a lot of interesting elements, but they don’t seem to fit together in the same book.)

#3 Ann Patchett wrote for Seventeen magazine for nine years. Before she ever published a novel, Meg Wolitzer was a winner of Seventeen’s fiction contest. Wolitzer’s The Wife (2003), my current book club read in advance of our March meeting, is a bitingly funny novel narrated by a woman trapped in a support role to her supposedly genius writer husband.

#4 I’ve heard great things about the recent film version of The Wife, which has Glenn Close as Joan Castleman. Close also stars as the Marquise de Merteuil in Dangerous Liaisons (1988). The 1782 Choderlos de Laclos novel was one of the texts we focused on in one of my freshman college courses, Screening Literature. For our final projects, we compared a few film adaptations. My group got Cruel Intentions (1999), a teen flick that provided one of Reese Witherspoon’s breakout roles.

#5 Witherspoon is giving Oprah a run for her money with her Hello Sunshine book club, which has chosen some terrific stuff. I happen to have read nine of her picks so far, and of those I particularly enjoyed Daisy Jones and the Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid.

#6 Daisy is said to have been inspired by the personal and professional complications of the band Fleetwood Mac. The musical roman à clef element isn’t necessary to understanding the novel, but is fun to ponder. In the same way, Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler features a musician modeled after singer/songwriter Bon Iver. I adored Shotgun Lovesongs and have a review of it coming out as part of Friday’s post, so consider this your teaser…

And there we have it! My first ever #6Degrees of Separation.

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

The Best Books of 2019: Some Runners-Up

I sometimes like to call this post “The Best Books You’ve Probably Never Heard Of (Unless You Heard about Them from Me)”. However, these picks vary quite a bit in terms of how hyped or obscure they are; the ones marked with an asterisk are the ones I consider my hidden gems of the year. Between this post and my Fiction/Poetry and Nonfiction best-of lists, I’ve now highlighted about the top 13% of my year’s reading.

Fiction:

Salt Slow by Julia Armfield: Nine short stories steeped in myth and magic. The body is a site of transformation, or a source of grotesque relics. Armfield’s prose is punchy, with invented verbs and condensed descriptions that just plain work. She was the Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner. I’ll be following her career with interest.

Salt Slow by Julia Armfield: Nine short stories steeped in myth and magic. The body is a site of transformation, or a source of grotesque relics. Armfield’s prose is punchy, with invented verbs and condensed descriptions that just plain work. She was the Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner. I’ll be following her career with interest.

*Agatha by Anne Cathrine Bomann: In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy, including meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm. This debut novel is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.

*Agatha by Anne Cathrine Bomann: In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy, including meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm. This debut novel is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.

A Single Thread by Tracy Chevalier: Chevalier is an American expat like me, but she’s lived in England long enough to make this very English novel convincing and full of charm. Violet Speedwell, 38, is an appealing heroine who has to fight for a life of her own in the 1930s. Who knew the hobbies of embroidering kneelers and ringing church bells could be so fascinating?

A Single Thread by Tracy Chevalier: Chevalier is an American expat like me, but she’s lived in England long enough to make this very English novel convincing and full of charm. Violet Speedwell, 38, is an appealing heroine who has to fight for a life of her own in the 1930s. Who knew the hobbies of embroidering kneelers and ringing church bells could be so fascinating?

Akin by Emma Donoghue: An 80-year-old ends up taking his sullen pre-teen great-nephew with him on a long-awaited trip back to his birthplace of Nice, France. The odd-couple dynamic works perfectly and makes for many amusing culture/generation clashes. Donoghue nails it: sharp, true-to-life and never sappy, with spot-on dialogue and vivid scenes.

Akin by Emma Donoghue: An 80-year-old ends up taking his sullen pre-teen great-nephew with him on a long-awaited trip back to his birthplace of Nice, France. The odd-couple dynamic works perfectly and makes for many amusing culture/generation clashes. Donoghue nails it: sharp, true-to-life and never sappy, with spot-on dialogue and vivid scenes.

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd: In 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Kidd paints a convincingly stark picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks. The prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people.

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd: In 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Kidd paints a convincingly stark picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks. The prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people.

*The Unpassing by Chia-Chia Lin: Bleak yet beautiful in the vein of David Vann’s work: the story of a Taiwanese immigrant family in Alaska and the bad luck and poor choices that nearly destroy them. This debut novel is full of atmosphere and the lowering forces of weather and fate.

*The Unpassing by Chia-Chia Lin: Bleak yet beautiful in the vein of David Vann’s work: the story of a Taiwanese immigrant family in Alaska and the bad luck and poor choices that nearly destroy them. This debut novel is full of atmosphere and the lowering forces of weather and fate.

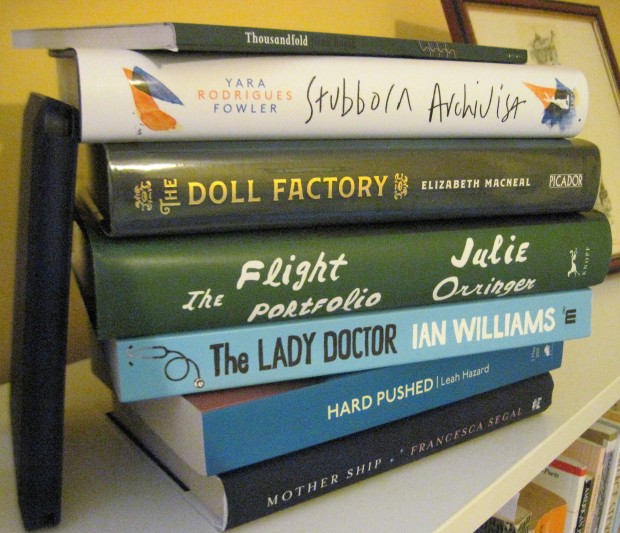

The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal: Set in the early 1850s and focusing on the Great Exhibition and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this reveals the everyday world of poor Londoners. It’s a sumptuous and believable fictional world, with touches of gritty realism. A terrific debut full of panache and promise.

The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal: Set in the early 1850s and focusing on the Great Exhibition and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this reveals the everyday world of poor Londoners. It’s a sumptuous and believable fictional world, with touches of gritty realism. A terrific debut full of panache and promise.

*The Heavens by Sandra Newman: Not a genre I would normally be drawn to (time travel), yet I found it entrancing. In her dreams Kate becomes Shakespeare’s “Dark Lady” and sees visions of a future burned city. The more she exclaims over changes in her modern-day life, the more people question her mental health. Impressive for how much it packs into 250 pages; something like a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Samantha Harvey.

*The Heavens by Sandra Newman: Not a genre I would normally be drawn to (time travel), yet I found it entrancing. In her dreams Kate becomes Shakespeare’s “Dark Lady” and sees visions of a future burned city. The more she exclaims over changes in her modern-day life, the more people question her mental health. Impressive for how much it packs into 250 pages; something like a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Samantha Harvey.

*In Love with George Eliot by Kathy O’Shaughnessy: Many characters, fictional and historical, are in love with George Eliot over the course of this debut novel. We get intriguing vignettes from Eliot’s life with her two great loves, and insight into her scandalous position in Victorian society. O’Shaughnessy mimics Victorian prose ably.

*In Love with George Eliot by Kathy O’Shaughnessy: Many characters, fictional and historical, are in love with George Eliot over the course of this debut novel. We get intriguing vignettes from Eliot’s life with her two great loves, and insight into her scandalous position in Victorian society. O’Shaughnessy mimics Victorian prose ably.

Daisy Jones and The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid: This story of the rise and fall of a Fleetwood Mac-esque band is full of verve and heart. It’s so clever how Reid delivers it all as an oral history of pieced-together interview fragments. Pure California sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, yet there’s nothing clichéd about it.

Daisy Jones and The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid: This story of the rise and fall of a Fleetwood Mac-esque band is full of verve and heart. It’s so clever how Reid delivers it all as an oral history of pieced-together interview fragments. Pure California sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, yet there’s nothing clichéd about it.

Graphic Novels:

*ABC of Typography by David Rault: From cuneiform to Comic Sans, this history of typography is delightful. Graphic designer David Rault wrote the whole thing, but each chapter has a different illustrator, so the book is like a taster course in comics styles. It is fascinating to explore the technical characteristics and aesthetic associations of various fonts.

*ABC of Typography by David Rault: From cuneiform to Comic Sans, this history of typography is delightful. Graphic designer David Rault wrote the whole thing, but each chapter has a different illustrator, so the book is like a taster course in comics styles. It is fascinating to explore the technical characteristics and aesthetic associations of various fonts.

*The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Dr. Lois Pritchard works at a medical practice in small-town Wales and treats embarrassing ailments at a local genitourinary medicine clinic. The tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also a lot of heartfelt moments. The drawing style recalls Alison Bechdel’s.

*The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Dr. Lois Pritchard works at a medical practice in small-town Wales and treats embarrassing ailments at a local genitourinary medicine clinic. The tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also a lot of heartfelt moments. The drawing style recalls Alison Bechdel’s.

Poetry:

*Thousandfold by Nina Bogin: This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds are a frequent presence. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature.

*Thousandfold by Nina Bogin: This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds are a frequent presence. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature.

Nonfiction:

*When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt: Aidt’s son Carl Emil died in 2015, having jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window during a mushroom-induced psychosis. The text is a collage of fragments. A playful disregard for chronology and a variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are ways of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

*When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt: Aidt’s son Carl Emil died in 2015, having jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window during a mushroom-induced psychosis. The text is a collage of fragments. A playful disregard for chronology and a variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are ways of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

*Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis, Davies moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir serves as a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote.

*Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis, Davies moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir serves as a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote.

*Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard: An empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room. This is a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering.

*Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard: An empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room. This is a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering.

*Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country by Pam Houston: Autobiographical essays full of the love of place, chiefly her Colorado ranch – a haven in a nomadic career, and a stand-in for the loving family home she never had. It’s about making your own way, and loving the world even – or especially – when it’s threatened with destruction. Highly recommended to readers of The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch.

*Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country by Pam Houston: Autobiographical essays full of the love of place, chiefly her Colorado ranch – a haven in a nomadic career, and a stand-in for the loving family home she never had. It’s about making your own way, and loving the world even – or especially – when it’s threatened with destruction. Highly recommended to readers of The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch.

*Dancing with Bees: A Journey back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. She clearly delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning. It’s a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. I ordered signed copies of this and the Simmons (below) directly from the authors via Twitter.

*Dancing with Bees: A Journey back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. She clearly delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning. It’s a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. I ordered signed copies of this and the Simmons (below) directly from the authors via Twitter.

*Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames by Lara Maiklem: Maiklem is a London mudlark, scavenging for what washes up on the shores of the Thames, including clay pipes, coins, armaments, pottery, and much more. A fascinating way of bringing history to life and imagining what everyday existence was like for Londoners across the centuries.

*Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames by Lara Maiklem: Maiklem is a London mudlark, scavenging for what washes up on the shores of the Thames, including clay pipes, coins, armaments, pottery, and much more. A fascinating way of bringing history to life and imagining what everyday existence was like for Londoners across the centuries.

Unfollow: A Journey from Hatred to Hope, Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church by Megan Phelps-Roper: Phelps-Roper grew up in a church founded by her grandfather and made up mostly of her extended family. Its anti-homosexuality message and picketing of military funerals became trademarks. This is an absorbing account of doubt and making a new life outside the only framework you’ve ever known.

Unfollow: A Journey from Hatred to Hope, Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church by Megan Phelps-Roper: Phelps-Roper grew up in a church founded by her grandfather and made up mostly of her extended family. Its anti-homosexuality message and picketing of military funerals became trademarks. This is an absorbing account of doubt and making a new life outside the only framework you’ve ever known.

*A Half Baked Idea: How Grief, Love and Cake Took Me from the Courtroom to Le Cordon Bleu by Olivia Potts: Bereavement memoir + foodie memoir = a perfect book for me. Potts left one very interesting career for another. Losing her mother when she was 25 and meeting her future husband, Sam, who put time and care into cooking, were the immediate spurs to trade in her wig and gown for a chef’s apron.

*A Half Baked Idea: How Grief, Love and Cake Took Me from the Courtroom to Le Cordon Bleu by Olivia Potts: Bereavement memoir + foodie memoir = a perfect book for me. Potts left one very interesting career for another. Losing her mother when she was 25 and meeting her future husband, Sam, who put time and care into cooking, were the immediate spurs to trade in her wig and gown for a chef’s apron.

*The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe: Not your average memoir. It’s based around train journeys – real and fictional, remembered and imagined; appropriate symbols for many of the book’s dichotomies: scheduling versus unpredictability, having or lacking a direction in life, monotony versus momentous events, and fleeting versus lasting connections.

*The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe: Not your average memoir. It’s based around train journeys – real and fictional, remembered and imagined; appropriate symbols for many of the book’s dichotomies: scheduling versus unpredictability, having or lacking a direction in life, monotony versus momentous events, and fleeting versus lasting connections.

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love by Dani Shapiro: On a whim, in her fifties, Shapiro sent off a DNA test kit and learned she was only half Jewish. Within 36 hours she found her biological father, who’d donated sperm as a medical student. It’s a moving account of her emotional state as she pondered her identity and what her sense of family would be in the future.

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love by Dani Shapiro: On a whim, in her fifties, Shapiro sent off a DNA test kit and learned she was only half Jewish. Within 36 hours she found her biological father, who’d donated sperm as a medical student. It’s a moving account of her emotional state as she pondered her identity and what her sense of family would be in the future.

*The Country of Larks: A Chiltern Journey by Gail Simmons: Reprising a trek Robert Louis Stevenson took nearly 150 years before, revisiting sites from a childhood in the Chilterns, and seeing the countryside that will be blighted by a planned high-speed railway line. Although the book has an elegiac air, Simmons avoids dwelling in melancholy, and her writing is a beautiful tribute to farmland that was once saturated with the song of larks.

*The Country of Larks: A Chiltern Journey by Gail Simmons: Reprising a trek Robert Louis Stevenson took nearly 150 years before, revisiting sites from a childhood in the Chilterns, and seeing the countryside that will be blighted by a planned high-speed railway line. Although the book has an elegiac air, Simmons avoids dwelling in melancholy, and her writing is a beautiful tribute to farmland that was once saturated with the song of larks.

(Books not pictured were read from the library or on Kindle.)

Coming tomorrow: Other superlatives and some statistics.

The Best Books from the First Half of 2019

My top 10 releases of 2019 thus far, in no particular order, are:

Not pictured: one more book read from the library; the Kindle represents two NetGalley reads.

General / Historical Fiction

Stubborn Archivist by Yara Rodrigues Fowler: What a hip, fresh approach to fiction. Broadly speaking, this is autofiction: like the author, the protagonist was born in London to a Brazilian mother and an English father. The book opens with fragmentary, titled pieces that look almost like poems in stanzas. The text feel artless, like a pure stream of memory and experience. Navigating two cultures (and languages), being young and adrift, and sometimes seeing her mother in herself: there’s a lot to sympathize with in the main character.

Stubborn Archivist by Yara Rodrigues Fowler: What a hip, fresh approach to fiction. Broadly speaking, this is autofiction: like the author, the protagonist was born in London to a Brazilian mother and an English father. The book opens with fragmentary, titled pieces that look almost like poems in stanzas. The text feel artless, like a pure stream of memory and experience. Navigating two cultures (and languages), being young and adrift, and sometimes seeing her mother in herself: there’s a lot to sympathize with in the main character.

The Flight Portfolio by Julie Orringer: Every day the Emergency Rescue Committee in Marseille interviews 60 refugees and chooses 10 to recommend to the command center in New York City. Varian and his staff arrange bribes, fake passports, and exit visas to get celebrated Jewish artists and writers out of the country via the Pyrenees or various sea routes. The story of an accidental hero torn between impossible choices is utterly compelling. This is richly detailed historical fiction at its best. My top book of 2019 so far.

The Flight Portfolio by Julie Orringer: Every day the Emergency Rescue Committee in Marseille interviews 60 refugees and chooses 10 to recommend to the command center in New York City. Varian and his staff arrange bribes, fake passports, and exit visas to get celebrated Jewish artists and writers out of the country via the Pyrenees or various sea routes. The story of an accidental hero torn between impossible choices is utterly compelling. This is richly detailed historical fiction at its best. My top book of 2019 so far.

Daisy Jones and The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid: This story of the rise and fall of a Fleetwood Mac-esque band is full of verve and heart, and it’s so clever how Reid delivers it all as an oral history of pieced-together interview fragments, creating authentic voices and requiring almost no footnotes or authorial interventions. It’s pure California sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, but there’s nothing clichéd about it. Instead, you get timeless rivalry, resentment, and unrequited or forbidden love; the clash of personalities and the fleeting nature of fame.

Daisy Jones and The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid: This story of the rise and fall of a Fleetwood Mac-esque band is full of verve and heart, and it’s so clever how Reid delivers it all as an oral history of pieced-together interview fragments, creating authentic voices and requiring almost no footnotes or authorial interventions. It’s pure California sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, but there’s nothing clichéd about it. Instead, you get timeless rivalry, resentment, and unrequited or forbidden love; the clash of personalities and the fleeting nature of fame.

Victorian Pastiche

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd: In the autumn of 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Kidd paints a convincingly stark picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks. Surgery before and after anesthesia and mythology (mermaids and selkies) are intriguing subplots woven through. Kidd’s prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people but also in more expansive musings on the dirty, bustling city.

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd: In the autumn of 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Kidd paints a convincingly stark picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks. Surgery before and after anesthesia and mythology (mermaids and selkies) are intriguing subplots woven through. Kidd’s prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people but also in more expansive musings on the dirty, bustling city.

The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal: Iris Whittle dreams of escaping Mrs Salter’s Doll Emporium and becoming a real painter. Set in the early 1850s and focusing on the Great Exhibition and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this also reveals the everyday world of poor Londoners. It’s a sumptuous and believable fictional world, with touches of gritty realism. If some characters seem to fit neatly into stereotypes (fallen woman, rake, etc.), be assured that Macneal is interested in nuances. A terrific debut full of panache and promise.

The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal: Iris Whittle dreams of escaping Mrs Salter’s Doll Emporium and becoming a real painter. Set in the early 1850s and focusing on the Great Exhibition and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this also reveals the everyday world of poor Londoners. It’s a sumptuous and believable fictional world, with touches of gritty realism. If some characters seem to fit neatly into stereotypes (fallen woman, rake, etc.), be assured that Macneal is interested in nuances. A terrific debut full of panache and promise.

Graphic Novel

The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Dr. Lois Pritchard works at a medical practice in small-town Wales and puts in two days a week treating embarrassing ailments at the local hospital’s genitourinary medicine clinic. The tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also a lot of heartfelt moments as Lois learns that a doctor is never completely off duty and you have no idea what medical or personal challenge will crop up next. The drawing style reminds me of Alison Bechdel’s.

The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Dr. Lois Pritchard works at a medical practice in small-town Wales and puts in two days a week treating embarrassing ailments at the local hospital’s genitourinary medicine clinic. The tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also a lot of heartfelt moments as Lois learns that a doctor is never completely off duty and you have no idea what medical or personal challenge will crop up next. The drawing style reminds me of Alison Bechdel’s.

Medical Nonfiction

Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson: Perfect for fans of I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell, this is a set of trenchant autobiographical essays about being in a female body, especially one wracked by pain. Gleeson ranges from the seemingly trivial to life-and-death matters as she writes about hairstyles, blood types, pregnancy, the abortion debate in Ireland and having a rare type of leukemia. The book feels timely and is inventive in how it brings together disparate topics to explore the possibilities and limitations of women’s bodies.

Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson: Perfect for fans of I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell, this is a set of trenchant autobiographical essays about being in a female body, especially one wracked by pain. Gleeson ranges from the seemingly trivial to life-and-death matters as she writes about hairstyles, blood types, pregnancy, the abortion debate in Ireland and having a rare type of leukemia. The book feels timely and is inventive in how it brings together disparate topics to explore the possibilities and limitations of women’s bodies.

Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard: An empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room. Excerpts from a midwife’s official notes – in italics and full of shorthand and jargon – are a neat window into the science and reality of the work. This is a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering. If you like books that follow doctors and nurses down hospital hallways, you’ll love it.

Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard: An empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room. Excerpts from a midwife’s official notes – in italics and full of shorthand and jargon – are a neat window into the science and reality of the work. This is a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering. If you like books that follow doctors and nurses down hospital hallways, you’ll love it.

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal: A visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of her daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU. As well as portraying her own state of mind, Segal crafts twinkly pen portraits of the others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums. Female friendship is thus a subsidiary theme in this exploration of desperate love and helplessness.

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal: A visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of her daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU. As well as portraying her own state of mind, Segal crafts twinkly pen portraits of the others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums. Female friendship is thus a subsidiary theme in this exploration of desperate love and helplessness.

Poetry

Thousandfold by Nina Bogin: This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds – along with their eggs and feathers – are a frequent presence. Often a particular object will serve as a totem as the poet remembers the most important people in her life. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature. I recommend it to fans of Linda Pastan.

Thousandfold by Nina Bogin: This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds – along with their eggs and feathers – are a frequent presence. Often a particular object will serve as a totem as the poet remembers the most important people in her life. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature. I recommend it to fans of Linda Pastan.

The three 4.5- or 5-star books that I read this year (and haven’t yet written about on here) that were not published in 2019 are:

Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods by Tishani Doshi [poetry]

Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods by Tishani Doshi [poetry]

Faces in the Water by Janet Frame

Priestdaddy: A Memoir by Patricia Lockwood

Tookie, the narrator, has a tough exterior but a tender heart. When she spent 10 years in prison for a misunderstanding-cum-body snatching, books helped her survive, starting with the dictionary. Once she got out, she translated her love of words into work as a bookseller at

Tookie, the narrator, has a tough exterior but a tender heart. When she spent 10 years in prison for a misunderstanding-cum-body snatching, books helped her survive, starting with the dictionary. Once she got out, she translated her love of words into work as a bookseller at

Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties.

Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties. What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness. Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.  City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.

Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.  Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…

Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…

(A sad one, this) The stillbirth of a child is an element in three memoirs I’ve read within a few months, Notes to Self by Emilie Pine, Threads by William Henry Searle, and The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

(A sad one, this) The stillbirth of a child is an element in three memoirs I’ve read within a few months, Notes to Self by Emilie Pine, Threads by William Henry Searle, and The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

I’d never heard of 4chan before, but then encountered it twice in quick succession, first in So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson and then in The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James

I’d never heard of 4chan before, but then encountered it twice in quick succession, first in So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson and then in The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James

An inside look at the anti-abortion movement in Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood and Crazy for God by Frank Schaeffer

An inside look at the anti-abortion movement in Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood and Crazy for God by Frank Schaeffer

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep.

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep. First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)

First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)  Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.

Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.  #4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

#4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]