Reading Wales Month: Tishani Doshi & Ruth Janette Ruck (#ReadingWales25)

It’s my first time participating in Reading Wales Month, hosted this year by Karen of BookerTalk. I happened to be reading a collection by a Welsh-Gujarati poet, and added a Welsh hill farming memoir to my stack so I could review two books towards this challenge.

A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi (2021)

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

In defiance of those who would destroy it, Doshi affirms the primacy of the body. The joyfully absurd “In a Dream I Give Birth to a Sumo Wrestler” ends with the lines “How easy to forget / that all we have are these bodies. That all of this, all of this is holy.” Poems are inspired by Emily Dickinson and Frida Kahlo as well as by real events that provoke outrage. The clever folktale-like pair “Microeconomics” and “Macroeconomics” contrasts a woman dutifully growing peas and trying to get ahead with exploitative situations: “One man sits on another if he can. … One man goes / into the mines for another man to sparkle.” I also found many wise words on grief. Doshi is a treasure. (Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

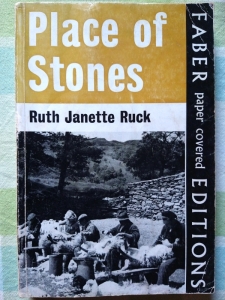

Place of Stones by Ruth Janette Ruck (1961)

“Farming is rather like the theatre—whatever happens the show must go on.”

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

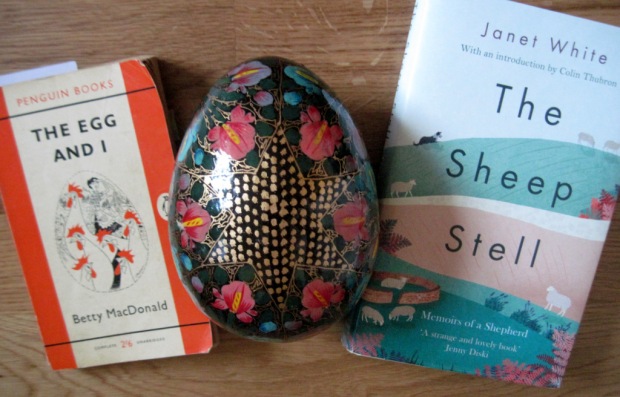

Even when things were going well, it was a hand-to-mouth existence and storms or illness could set everything back. The Rucks renovated a nearby cottage to serve as a holiday let. Another windfall came in the bizarre form of a nearby film shoot by Twentieth Century Fox (The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, starring Ingrid Bergman). Mountainous North Wales stood in for China, and the film crew hired Ruck as a driver and, like many locals, as an occasional extra. This book was light and mildly entertaining, though probably more detailed about everyday farm work and projects than I needed. I was reminded again of Doreen Tovey, especially in the passage about Topsy the pet black sheep, but also this time of Betty Macdonald (The Egg and I) and Janet White (The Sheep Stell). (Secondhand – Lions bookshop, Alnwick) ![]()

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep.

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep.

First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)

First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)  Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.

Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.

#4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

#4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

I’m reviewing this reissued memoir for the TLS. It’s a delightful story of finding contentment in the countryside, whether on her own or with family. White, now in her eighties, has been a shepherd for six decades in the British Isles and in New Zealand. While there’s some darker material here about being stalked by a spurned suitor, the tone is mostly lighthearted. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s enjoyed books by Gerald Durrell, James Herriot and Doreen Tovey.

I’m reviewing this reissued memoir for the TLS. It’s a delightful story of finding contentment in the countryside, whether on her own or with family. White, now in her eighties, has been a shepherd for six decades in the British Isles and in New Zealand. While there’s some darker material here about being stalked by a spurned suitor, the tone is mostly lighthearted. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s enjoyed books by Gerald Durrell, James Herriot and Doreen Tovey. Mrs. Creasy disappears one Monday in June 1976, and ten-year-old Grace Bennett and her friend Tilly are determined to figure out what happened. I have a weakness for precocious child detectives (from Harriet the Spy to Flavia de Luce), so I enjoyed Grace’s first-person sections, but it always feels like cheating to me when an author realizes they can’t reveal everything from a child’s perspective so add in third-person narration and flashbacks. These fill in the various neighbors’ sad stories and tell of a rather shocking act of vigilante justice they together undertook nine years ago.

Mrs. Creasy disappears one Monday in June 1976, and ten-year-old Grace Bennett and her friend Tilly are determined to figure out what happened. I have a weakness for precocious child detectives (from Harriet the Spy to Flavia de Luce), so I enjoyed Grace’s first-person sections, but it always feels like cheating to me when an author realizes they can’t reveal everything from a child’s perspective so add in third-person narration and flashbacks. These fill in the various neighbors’ sad stories and tell of a rather shocking act of vigilante justice they together undertook nine years ago.

My first collection from the prolific Pulitzer winner. Some of the poems are built around self-interrogation, with a question and answer format; several reflect on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first and last poems are both entitled “Vita Nova,” while another in the middle is called “The New Life.” I enjoyed the language of spring in the first “Vita Nova” and in “The Nest,” but I was unconvinced by much of what Glück writes about love and self-knowledge, some of it very clichéd indeed, e.g. “I found the years of the climb upward / difficult, filled with anxiety” (from “Descent to the Valley”) and “My life took me many places, / many of them very dark” (from “The Mystery”).

My first collection from the prolific Pulitzer winner. Some of the poems are built around self-interrogation, with a question and answer format; several reflect on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first and last poems are both entitled “Vita Nova,” while another in the middle is called “The New Life.” I enjoyed the language of spring in the first “Vita Nova” and in “The Nest,” but I was unconvinced by much of what Glück writes about love and self-knowledge, some of it very clichéd indeed, e.g. “I found the years of the climb upward / difficult, filled with anxiety” (from “Descent to the Valley”) and “My life took me many places, / many of them very dark” (from “The Mystery”).