April 3rd Releases by Emily Jungmin Yoon & Jean Hannah Edelstein

It’s not often that I manage to review books for their publication date rather than at the end of the month, but these two were so short and readable that I polished them off over the first few days of April. So, out today in the UK: a poetry collection about Asian American identity and environmental threat, and a memoir in miniature about how body parts once sexualized and then functionalized are missed once they’re gone.

Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon (2024)

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

Published in the USA by Knopf on October 22, 2024. With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein

From my Most Anticipated list. I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir This Really Isn’t About You, and I regularly read her Substack. This micro-memoir in three essays explores the different roles breasts have played in her life: “Sex” runs from the day she went shopping for her first bra as a teenager with her mother through to her early thirties living in London. Edelstein developed early and eventually wore size DD, which attracted much unwanted attention in social situations and workplaces alike. (And not just a slightly sleazy bar she worked in, but an office, too. Twice she was groped by colleagues; the second time she reported it. But: drunk, Christmas party, no witnesses; no consequences.) “It felt like a punishment, a consequence of my own behavior (being a woman, having a fun night out, doing these things while having large breasts),” she writes.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

Although this is a likable book, the retelling is quite flat; better that than mawkish, certainly, but none of the experiences feel particularly unique. It’s more a generic rundown of what it’s like to be female – which, yes, varies to an extent but not that much if we’re talking about the male gaze. There wasn’t the same spark or wit that I found in Edelstein’s first book. Perhaps in the context of a longer memoir, I would have appreciated these essays more.

With thanks to Phoenix for the free copy for review.

This and That (The January Blahs)

The January blahs have well and truly arrived. The last few months of 2023 (December in particular) were too full: I had so much going on that I was always rushing from one thing to the next and worrying I didn’t have the time to adequately appreciate any of it. Now my problem is the opposite: very little to do, work or otherwise; not much on the calendar to look forward to; and the weather and house so cold I struggle to get up each morning and push past the brain fog to settle to any task. As I kept thinking to myself all autumn, there has to be a middle ground between manic busyness and boredom. That’s the head space where I’d like to be living, instead of having to choose between hibernation and having no time to myself.

At least these frigid January days are good for being buried in books. Unusually for me, I’m in the middle of seven doorstoppers, including King by Jonathan Eig (perfect timing as Monday is Martin Luther King Jr. Day), Wellness by Nathan Hill, and Babel by R.F. Kuang (a nominal buddy read with my husband).

Another is Carol Shields’s Collected Short Stories for a buddy rereading project with Marcie of Buried in Print. We’re partway through the first volume, Various Miracles, after a hiccup when we realized my UK edition had a different story order and, in fact, different contents – it must have been released as a best-of. We’ll read one volume per month in January–March. I also plan to join Heaven Ali in reading at least one Margaret Drabble book this year. I have The Waterfall lined up, and her Arnold Bennett biography lurking. Meanwhile, the Read Indies challenge, hosted by Karen and Lizzy in February, will be a great excuse to catch up on some review books from independent publishers.

Literary prize season will be heating up soon. I put all of the Women’s Prize (fiction and nonfiction!) dates on my calendar and I have a running list, in a file on my desktop, of all the novels I’ve come across that would be eligible for this year’s race. I’m currently reading two memoirs from the Nero Book Awards nonfiction shortlist. Last year it looked like the Folio Prize was set to replace the Costa Awards, giving category prizes and choosing an overall winner. But then another coffee chain, Caffè Nero, came along and picked up the mantle.

This year the Folio has been rebranded as The Writers’ Prize, again with three categories, which don’t quite overlap with the Costa/Nero ones. The Writers’ Prize shortlists just came out on Tuesday. I happen to have read one of the poetry nominees (Chan) and one of the fiction (Enright). I’m going to have a go at reading the others that I can source via the library. I’ll even try The Bee Sting given it’s on both the Nero and Writers’ shortlists (ditto the Booker) and I have a newfound tolerance of doorstoppers.

As for my own literary prize involvement, my McKitterick Prize manuscript longlist is due on the 31st. I think I have it finalized. Out of 80 manuscripts, I’ve chosen 5. The first 3 stood out by a mile, but deciding on the other 2 was really tricky. We judges are meeting up online next week.

I’m listening to my second-ever audiobook, an Audible book I was sent as a birthday gift: There Plant Eyes by M. Leona Godin. My routine is to find a relatively mindless data entry task to do and put on a chapter at a time.

There are a handful of authors I follow on Substack to keep up with what they’re doing in between books: Susan Cain, Jean Hannah Edelstein, Catherine Newman, Anne Boyd Rioux, Nell Stevens (who seems to have gone dormant?), Emma Straub and Molly Wizenberg. So far I haven’t gone for the paid option on any of the subscriptions, so sometimes I don’t get to read the whole post, or can only see selected posts. But it’s still so nice to ‘hear’ these women’s voices occasionally, right in my inbox.

My current earworms are from Belle and Sebastian’s Late Developers album, which I was given for Christmas. These lyrics from the title track – saved, refreshingly, for last; it’s a great strategy to end on a peppy song (an uplifting anthem with gospel choir and horn section!) instead of tailing off – feel particularly apt:

Live inside your head

Get out of your bed

Brush the cobwebs off

I feel most awake and alive when I’m on my daily walk by the canal. It’s such a joy to hear the birdsong and see whatever is out there to be seen. The other day there was a red kite zooming up from a field and over the houses, the sun turning his tail into a burnished chestnut. And on the opposite bank, a cuboid rump that turned out to belong to a muntjac deer. Poetry fragments from two of my bedside books resonated with me.

This is the earnest work. Each of us is given

only so many mornings to do it—

to look around and love

the oily fur of our lives,

the hoof and the grass-stained muzzle.

Days I don’t do this

I feel the terror of idleness

like a red thirst.

That is from “The Deer,” from Mary Oliver’s House of Light, and reminds me that it’s always worthwhile to get outside and just look. Even if what you’re looking at doesn’t seem to be extraordinary in any way…

Importance leaves me cold,

as does all the information that is classed as ‘news’.

I like those events that the centre ignores:

small branches falling, the slow decay

of wood into humus, how a puddle’s eye

silts up slowly, till, eventually,

the birds can’t bathe there. I admire the edge;

the sides of roads where the ragwort blooms

low but exotic in the traffic fumes;

the scruffy ponies in a scrubland field

like bits of a jigsaw you can’t complete;

the colour of rubbish in a stagnant leat.

There are rarest enjoyments, for connoisseurs

of blankness, an acquired taste,

once recognised, it’s impossible to shake,

this thirst for the lovely commonplace.

(from “Six Poems on Nothing,” III by Gwyneth Lewis, in Parables & Faxes)

This was basically a placeholder post because who knows when I’ll next finish any books and write about them … probably not until later in the month. But I hope you’ve found at least one interesting nugget!

What ‘lovely commonplace’ things are keeping you going this month?

Three Out-of-the-Ordinary Memoirs: Kalb, Machado, McGuinness

Recently I have found myself drawn to memoirs that experiment with form. I’ve read so many autobiographical narratives at this point that, if it’s to stand out for me, a book has to offer something different, such as a second-person point-of-view or a structure of linked essays. Here are a few such that I’ve read this year but not written about yet. All have strong themes of memory and the creation of the self or the family.

Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb (2020)

You know from the jokes: Jewish (grand)mothers are renowned for their fiercely protective, unconditional love, but also for their tendency to nag. Both sides of a stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny and heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if straight to Kalb from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother, Barbara “Bobby” Bell.

You know from the jokes: Jewish (grand)mothers are renowned for their fiercely protective, unconditional love, but also for their tendency to nag. Both sides of a stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny and heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if straight to Kalb from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother, Barbara “Bobby” Bell.

Bobby gives her beloved Bessie a tour through four generations of strong women, starting with her own mother, Rose, and her lucky escape from a Belarus shtetl. The formidable émigré ended up in a tiny Brooklyn apartment, where she gave birth to five children on the dining room table. Bobby and her husband, a real estate entrepreneur and professor, had one daughter, Robin, who in turn had one daughter, Bess. Bobby and Robin had a fraught relationship, but Bess’s birth seemed to reset the clock. Grandmother and granddaughter had a special bond: Bobby was the one to take her to preschool and wait outside the door until she was sure she’d be okay, and always the one to pick her up from sleepovers gone wrong.

Kalb is a Los Angeles-based writer for Jimmy Kimmel Live! With her vivid scene-setting and comic timing, you can see why she’s earned a Writers Guild Award and an Emmy nomination. But she also had great material to work with: Bobby’s e-mails and verbatim voicemail messages are hilarious. Kalb dots in family photographs and recreates in-person and phone conversations, with her grandmother forthrightly questioning her fashion choices and non-Jewish boyfriend. As the title phrase shows, Bobby felt she was the only one who would come forward with all this (unwanted but) necessary advice. Kalb keeps things snappy, alternating between narrative chapters and the conversations and covering a huge amount of family history in just 200 pages. It gets a little sentimental towards the end, but with her grandmother’s death still fresh you can forgive her that. This was a real delight.

My rating:

My thanks to Zoe Hood and Kimberley Nyamhondera of Little, Brown (Virago) for the free PDF copy for review.

In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado (2019)

I’m stingy with 5-star ratings because, for me, giving a book top marks means a) it’s a masterpiece, b) it’s a game/mind/life changer, and/or c) it expands the possibilities of its particular genre. In the Dream House fits all three criteria. (Somewhat to my surprise, given that I couldn’t get through more than half of Machado’s acclaimed story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, and only enjoyed it in parts.)

Much has been written about this memoir of an abusive same-sex relationship since its U.S. release in November. I feel I have little to add to the conversation beyond my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scenes; gleefully does away with the chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory – in other words, the boring bits – that most writers would so slavishly detail; and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to constantly interrogate her experiences and perceptions.

Most of the book is, like the Kalb, in the second person, but in this case the narration is not addressing a specific other person; instead, it’s looking back at the self that was caught in this situation (“If, one day, a milky portal had opened up in your bedroom and an older version of yourself had stepped out and told you what you know now, would you have listened?”), as well as – what the second person does best – putting the reader right into the narrative.

Most of the book is, like the Kalb, in the second person, but in this case the narration is not addressing a specific other person; instead, it’s looking back at the self that was caught in this situation (“If, one day, a milky portal had opened up in your bedroom and an older version of yourself had stepped out and told you what you know now, would you have listened?”), as well as – what the second person does best – putting the reader right into the narrative.

The “Dream House” is the Victorian house where Machado lived with her ex-girlfriend in Bloomington, Indiana for two years while she started an MFA course. It was a paradise until it wasn’t; it was a perfect relationship until it wasn’t. No one, least of all her, would have believed the perky little blonde writer she fell for would turn sadistic. A lot of it was emotional manipulation and verbal and psychological abuse, but there was definitely a physical element as well. Fear and self-doubt kept her trapped in a fairy tale that had long since turned into a nightmare. Writing it all out seven years later, the trauma was still there. Yet there was no tangible evidence (a police report, a restraining order, photos of bruises) to site her abuse anywhere outside of her memory. How fleeting, yet indelible, it had all been.

The book is in relatively short sections headed “Dream House as _________” (fill in the blank with everything from “Time Travel” to “Confession”), and the way that she pecks at her memories from different angles is perfect for recreating the spiral of confusion and despair. She also examines the history of our understanding of queer domestic violence: lesbian domestic violence, specifically, wasn’t known about until 30-some years ago.

The story has a happy ending in that Machado is now happily married. The bizarre twist, though, is that her wife, YA author Val Howlett, was the girlfriend of the woman in the Dream House when they first met. To start with, it was an “open relationship” (or at least the blonde told her so) that Machado reluctantly got in the middle of, before Val drifted away. That the two of them managed to reconnect, and got past their mutual ex, is truly astonishing. (See some super-cute photos from their wedding here.)

Some favorite lines:

“Clarity is an intoxicating drug, and you spent almost two years without it, believing you were losing your mind”

“That there’s a real ending to anything is, I’m pretty sure, the lie of all autobiographical writing. You have to choose to stop somewhere. You have to let the reader go.”

My rating:

I read an e-copy via NetGalley.

Other People’s Countries: A Journey into Memory by Patrick McGuinness (2014)

This is a wonderfully atmospheric tribute to Bouillon, Belgium, a Wallonian border town with its own patois. However, it’s chiefly a memoir about the maternal side of the author’s family, which had lived there for generations. McGuinness grew up spending summers in Bouillon with his grandparents and aunt. Returning to the place as an adult, he finds it half-derelict but still storing memories around every corner.

It is as much a tour through memory as through a town, reflecting on how our memories are bound up with particular sites and objects – to the extent that I don’t think I would find McGuinness’s Bouillon even if I went back to Belgium. “When I’m asked about events in my childhood, about my childhood at all, I think mostly of rooms. I think of times as places, with walls and windows and doors,” he writes. The book is also about the nature of time: Bouillon seems like a place where time stands still or moves more slowly, allowing its residents (including his grandfather, and Paprika, “Bouillon’s laziest man, who held a party to celebrate sixty years on the dole”) a position of smug idleness.

It is as much a tour through memory as through a town, reflecting on how our memories are bound up with particular sites and objects – to the extent that I don’t think I would find McGuinness’s Bouillon even if I went back to Belgium. “When I’m asked about events in my childhood, about my childhood at all, I think mostly of rooms. I think of times as places, with walls and windows and doors,” he writes. The book is also about the nature of time: Bouillon seems like a place where time stands still or moves more slowly, allowing its residents (including his grandfather, and Paprika, “Bouillon’s laziest man, who held a party to celebrate sixty years on the dole”) a position of smug idleness.

The book is in short vignettes, some as short as a paragraph; each is a separate piece with a title that remembers a particular place, event or local character. Some are poems, and there are also recipes and an inventory. The whole is illustrated with frequent period or contemporary black-and-white photographs. It’s an altogether lovely book that overcomes its narrow local interest to say something about how the past remains alive for us.

Some favorite lines:

“that hybrid long-finished but real-time-unfolding present tense … reflects the inside of our lives far better than those three stooges, the past, present and future”

a fantastic last line: “What I want to say is: I misremember all this so vividly it’s as if it only happened yesterday.”

My rating:

I read a public library copy.

Other unusual memoirs I’ve loved and reviewed here:

Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth (essays, experimental structures)

Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth (essays, experimental structures)

Winter Journal by Paul Auster (second person)

This Really Isn’t about You by Jean Hannah Edelstein (nonchronological)

Traveling with Ghosts by Shannon Leone Fowler (short sections and time shifts)

The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe (nonchronological essays)

Any offbeat memoirs you can recommend?

The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe

Everything was in its place.

Particulars moved

along designated rails.

Even the arranged meeting

occurred. […]

In paradise lost

of probability.

From “Railway station” by Wisława Szymborska

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

From “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop

This is not your average memoir. For one thing, it ends with 34 pages of notes and bibliography. Sophie Ratcliffe is an associate professor of English at the University of Oxford, and it’s clear that her life and the narrative have been indelibly shaped by literature. In this work of creative nonfiction she is particularly interested in the lives and works of Leo Tolstoy and Anthony Trollope and the women they loved. For another, the book is based around train journeys – real and fictional, remembered and imagined. Trains are appropriate symbols for many of the book’s dichotomies: scheduling versus unpredictability, having or lacking a direction in life, monotony versus momentous events, and fleeting versus lasting connections.

This is not your average memoir. For one thing, it ends with 34 pages of notes and bibliography. Sophie Ratcliffe is an associate professor of English at the University of Oxford, and it’s clear that her life and the narrative have been indelibly shaped by literature. In this work of creative nonfiction she is particularly interested in the lives and works of Leo Tolstoy and Anthony Trollope and the women they loved. For another, the book is based around train journeys – real and fictional, remembered and imagined. Trains are appropriate symbols for many of the book’s dichotomies: scheduling versus unpredictability, having or lacking a direction in life, monotony versus momentous events, and fleeting versus lasting connections.

Each chapter, marked with a location and a year, functions as a mini-essay; as the nonchronological pieces accrete you develop a sense of what have been the most important elements of Ratcliffe’s life. One was her father’s death from cancer when she was 13, an early loss that inevitably affected the years that followed. Another was a love affair with a married photographer 30 years her senior. A number of chapters are addressed directly to this ex-lover in the second person. Although they’ve had no contact since she got married, she still thinks about him – and wonders if she’ll have a right to mourn him when he dies.

Could she have been his muse, as Kate Field was for Trollope? Field appeared in fictional guises in much of his work and thereby inspired Anna Karenina, for Tolstoy was a devoted reader of Trollope and gave his heroine a penchant for reading English novels, too. Ratcliffe seems to see herself in Anna, a wife and mother who longs for a life of her own: she writes of her love for her two children but also of the boredom that comes with motherhood’s minutiae.

Sophie Ratcliffe

Much of life’s daily tedium is bound up in physical objects, like the random objects that litter the cover. “I am a lover of small things – and of clutter,” Ratcliffe confesses. She notes that generations of literary critics have asked what was in the red handbag Anna Karenina left behind, too. What does such lost property say about its owner? What can be saved from a life in which loss is so prevalent? These are questions the book explores through its metaphors, stories and memories. It ends with the hope that writing things down gives them meaning.

If you enjoy nonstandard memoirs (like Jean Hannah Edelstein’s This Really Isn’t About You) and books about how what we read makes us who we are (such as Samantha Ellis’s How to Be a Heroine and Lucy Mangan’s Bookworm), you have a real treat in store here.

Some favorite lines:

“Life is in the between-ness, the space in the margins – not in the headlines.”

“Books, like trains, are another way of tricking time, of moving to a different beat, a different space.”

“Has my reading been a way of keeping me company – of helping me through the worlds of nearlys and barelys and the feelings of missing, and the hopeless messiness?”

“Writing is better than nothing. Better than thin air.”

My rating:

With thanks to William Collins for the free copy for review.

I first heard of the author when she was a Wellcome Book Prize judge in 2018. I was delighted to be invited to take part in the blog tour for The Lost Properties of Love.

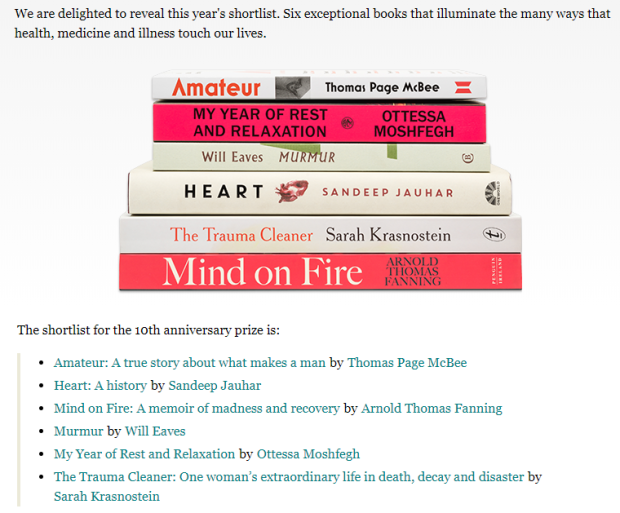

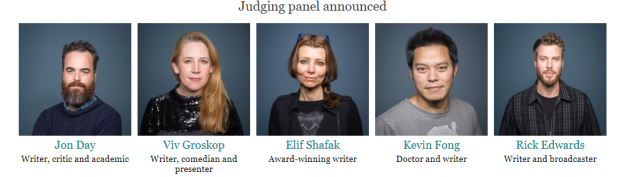

The Wellcome Book Prize 2019 Shortlist: Reactions, Strategy, Predictions

The Wellcome Book Prize longlist was announced at midnight yesterday morning. From the prize’s website, you can click on any of the six books’ covers, titles or authors for more information. See also Laura’s reactions post.

Our shadow panel successfully predicted four of these six, with the remaining two (Fanning and Moshfegh) coming as something of a surprise. It’s a shame This Really Isn’t About You didn’t make it through, as it was a collective favorite of the panel’s, but I’m relieved I now don’t have to read Astroturf and Polio. I’m hoping that the rest of the shadow panel will enjoy Mind on Fire more than I did, and will be willing to give My Year of Rest and Relaxation a go even though it’s one of those Marmite books.

There are four nonfiction books and two novels on the shortlist. Given that novelist Elif Shafak is the chair of judges in this 10th anniversary year, it could make sense for there to be a fiction winner this year; this would also cement an alternating pattern of fiction / nonfiction / fiction, following on from Mend the Living and To Be a Machine. If that’s the case, since Moshfegh’s novel, though a hugely enjoyable satire on modern disconnection and emotional numbness, doesn’t have the strongest health theme, perhaps we will indeed see Murmur take the prize, as Annabel predicted in her review. Alternatively, Amateur feels like a timely take on gender configurations, so maybe, as Laura guesses, it will win. I don’t think I could see the other four winning. (Then again, my panel’s predictions were wildly off base in 2017!)

There are four nonfiction books and two novels on the shortlist. Given that novelist Elif Shafak is the chair of judges in this 10th anniversary year, it could make sense for there to be a fiction winner this year; this would also cement an alternating pattern of fiction / nonfiction / fiction, following on from Mend the Living and To Be a Machine. If that’s the case, since Moshfegh’s novel, though a hugely enjoyable satire on modern disconnection and emotional numbness, doesn’t have the strongest health theme, perhaps we will indeed see Murmur take the prize, as Annabel predicted in her review. Alternatively, Amateur feels like a timely take on gender configurations, so maybe, as Laura guesses, it will win. I don’t think I could see the other four winning. (Then again, my panel’s predictions were wildly off base in 2017!)

In a press release Shafak commented on behalf of the judging panel: “The judging panel is very excited and proud to present this astonishing collection of titles, ranging from the darkly comic to the searingly honest. While the books selected are strikingly unique in their subject matter and style, the rich variety of writing also shares much in common: each is raw and brave and inspirational, deepening our understanding of what it truly means to be human through the transformative power of storytelling.”

Murmur is the only one of the six that I haven’t already read; I only read Part I and gave the rest a quick skim. So I resumed it yesterday at Part II. I might not get a chance to revisit the other shortlisted books, but I will be eager to see what the rest of the shadow panel make of the books they haven’t read yet. We will all be taking part in an official Wellcome Book Prize blog tour put on by Midas PR. I’ll also look into whether we can arrange Q&As with the shortlisted authors to run on our blogs in the coming weeks.

I won a limited edition David Shrigley Books Are My Bag tote bag in a Wellcome Collection competition on Twitter. Fittingly, it arrived on the shortlist announcement day!

The Wellcome Book Prize winner will be revealed at an evening ceremony at the Wellcome Collection on Wednesday, May 1st.

Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for more reviews and predictions.

Which book from the shortlist would you most like to read?

Wellcome Book Prize 2019: Announcing Our Shadow Panel Shortlist

Here’s a recap of what’s on the Wellcome Book Prize longlist, with links to all the reviews that have gone up on our blogs so far:

Amateur: A true story about what makes a man by Thomas Page McBee

Astroturf by Matthew Sperling

Educated by Tara Westover

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi

Heart: A history by Sandeep Jauhar

Mind on Fire: A memoir of madness and recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning

Murmur by Will Eaves

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

Polio: The odyssey of eradication by Thomas Abraham

Sight by Jessie Greengrass

The Trauma Cleaner: One woman’s extraordinary life in death, decay and disaster by Sarah Krasnostein

This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein

Together we have chosen the six* books we would like to see advance to the shortlist. This is based on our own reading and interest, but also on what we think best fits the prize’s aim, as stated on the website:

To be eligible for entry, a book should have a central theme that engages with some aspect of medicine, health or illness. At some point, medicine touches all our lives. Books that find stories in those brushes with medicine are ones that add new meaning to what it means to be human. The subjects these books grapple with might include birth and beginnings, illness and loss, pain, memory, and identity. In keeping with its vision and goals, the Wellcome Book Prize aims to excite public interest and encourage debate around these topics.

Here are the books (*seven of them, actually) that we’ll be rooting for – we had a tie on a couple:

Amateur: A true story about what makes a man by Thomas Page McBee

Educated by Tara Westover

Heart: A history by Sandeep Jauhar

Murmur by Will Eaves

Sight by Jessie Greengrass

The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein

This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein

The official Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday the 19th. I’ll check back in on Wednesday with our reactions to the shortlist and the plan for covering the rest of the books we haven’t already read.

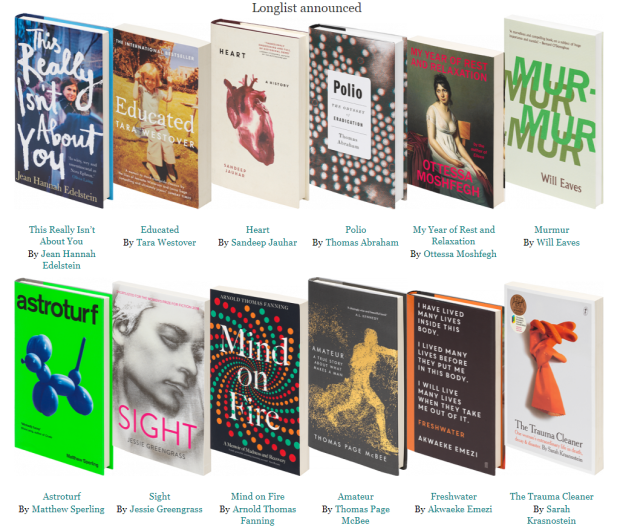

The Wellcome Book Prize 2019 Longlist: Reactions & Shadow Panel Reading Strategy

The 2019 Wellcome Book Prize longlist was announced on Tuesday. From the prize’s website, you can click on any of these 12 books’ covers, titles or authors to get more information about them.

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the prize. As always, it’s a strong and varied set of nominees, with an overall focus on gender and mental health. Here are some initial thoughts (see also Laura’s thorough rundown of the 12 nominees):

- I correctly predicted just two, Sight by Jessie Greengrass and Heart: A History by Sandeep Jauhar, but had read another three: This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein, Amateur by Thomas Page McBee, and Educated by Tara Westover (reviewed for BookBrowse).

- I’m particularly delighted to see Edelstein on the longlist as her book was one of my runners-up from last year and deserves more attention.

- I’m not personally a huge fan of the Greengrass or McBee books, but can certainly see why the judges thought them worthy of inclusion.

- Though it’s a brilliant memoir, I never would have thought to put Educated on my potential Wellcome list. However, the more I think about it, the more health elements it has: her father’s possible bipolar disorder, her brother’s brain damage, her survivalist family’s rejection of modern medicine, her mother’s career in midwifery and herbalism, and her own mental breakdown at Cambridge.

- Books I knew about and was keen to read but hadn’t thought of in conjunction with the prize: The Trauma Cleaner by Sarah Krasnostein and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh.

- Novels I had heard of but wasn’t necessarily interested in beforehand: Murmur by Will Eaves and Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi. I went to get Freshwater from the library the afternoon of the longlist announcement and am now 60 pages in. I’d be tempted to call it this year’s Stay with Me except that the magic realist elements are much stronger here, reminding me of what I know about work by Chigozie Obioma and Ben Okri. The novel is narrated in the first person plural by a pair of (gods? demons? spirits?) inhabiting Ada’s head.

- And lastly, there are a few books I had never even heard of: Polio: The Odyssey of Eradication by Thomas Abraham, Mind on Fire: A Memoir of Madness and Recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning, and Astroturf by Matthew Sperling. I’m keen on the Fanning but not so much on the other two. Polio will likely make it to the shortlist as this year’s answer to The Vaccine Race; if it does, I’ll read it then.

Some statistics on this year’s longlist, courtesy of a press release sent by Midas PR:

- Five novels (two more than last year – I think we can see the influence of novelist Elif Shafak), five memoirs, one biography, and one further nonfiction title

- Six debut authors

- Six titles from independent publishers (Canongate, CB Editions, Faber & Faber, Oneworld, Hurst Publishers, and The Text Publishing Company)

- Most of the authors are British or American, while Fanning is Irish (Emezi is Nigerian-American, Jauhar is Indian-American, and Krasnostein is Australian-American).

Chair of judges Elif Shafak writes: “In a world that remains sadly divided into echo chambers and mental ghettoes, this prize is unique in its ability to connect various disciplines: medicine, health, literature, art and science. Reading and discussing at length all the books on our list has been fascinating from the very start. We now have a wonderful longlist, of which we are all very proud. Although it sure won’t be easy to choose the shortlist, and then, finally, the winner, I am thrilled about and truly grateful for this fascinating journey through stories, ideas, ground-breaking research and revolutionary knowledge.”

We of the shadow panel have divided up the longlist titles between us as follows (though we may well each get hold of and read more of the books, simply out of personal interest) and will post reviews on our blogs within the next five weeks.

Amateur: A true story about what makes a man by Thomas Page McBee – LAURA

Astroturf by Matthew Sperling – PAUL

Educated by Tara Westover – CLARE

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi – REBECCA

Heart: A history by Sandeep Jauhar – LAURA

Mind on Fire: A memoir of madness and recovery by Arnold Thomas Fanning – REBECCA

Murmur by Will Eaves – PAUL

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh – CLARE

Polio: The odyssey of eradication by Thomas Abraham – ANNABEL

[Sight by Jessie Greengrass – 4 of us have read this; I’ll post a composite of our thoughts]

The Trauma Cleaner: One woman’s extraordinary life in death, decay and disaster by Sarah Krasnostein – ANNABEL

This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein – LAURA

The Wellcome Book Prize shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, March 19th, and the winner will be revealed on Wednesday, May 1st.

We plan to choose our own shortlist to announce on Friday, March 15th. Follow along here and on Halfman, Halfbook, Annabookbel, A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall for reviews and predictions.

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,

Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.” Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s  Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

In Shock by Rana Awdish: The doctor became the patient when Awdish, seven months pregnant, was rushed into emergency surgery with excruciating pain due to severe hemorrhaging into the space around her liver, later explained by a ruptured tumor. Having experienced brusque, cursory treatment, even from colleagues at her Detroit-area hospital, she was convinced that doctors needed to do better. This memoir is a gripping story of her own medical journey and a fervent plea for compassion from medical professionals.

In Shock by Rana Awdish: The doctor became the patient when Awdish, seven months pregnant, was rushed into emergency surgery with excruciating pain due to severe hemorrhaging into the space around her liver, later explained by a ruptured tumor. Having experienced brusque, cursory treatment, even from colleagues at her Detroit-area hospital, she was convinced that doctors needed to do better. This memoir is a gripping story of her own medical journey and a fervent plea for compassion from medical professionals.  Doctor by Andrew Bomback: Part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, this is a wide-ranging look at what it’s like to be a doctor. Bomback is a kidney specialist; his wife is also a doctor, and his father, fast approaching retirement, is the kind of old-fashioned, reassuring pediatrician who knows everything. Even the author’s young daughter likes playing with a stethoscope and deciding what’s wrong with her dolls. In a sense, then, Bomback uses fragments of family memoir to compare the past, present and likely future of medicine.

Doctor by Andrew Bomback: Part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, this is a wide-ranging look at what it’s like to be a doctor. Bomback is a kidney specialist; his wife is also a doctor, and his father, fast approaching retirement, is the kind of old-fashioned, reassuring pediatrician who knows everything. Even the author’s young daughter likes playing with a stethoscope and deciding what’s wrong with her dolls. In a sense, then, Bomback uses fragments of family memoir to compare the past, present and likely future of medicine.

A Moment of Grace by Patrick Dillon [skimmed]: A touching short memoir of the last year of his wife Nicola Thorold’s life, in which she battled acute myeloid leukemia. Dillon doesn’t shy away from the pain and difficulties, but is also able to summon up some gratitude.

A Moment of Grace by Patrick Dillon [skimmed]: A touching short memoir of the last year of his wife Nicola Thorold’s life, in which she battled acute myeloid leukemia. Dillon doesn’t shy away from the pain and difficulties, but is also able to summon up some gratitude.  Get Well Soon: Adventures in Alternative Healthcare by Nick Duerden: British journalist Nick Duerden had severe post-viral fatigue after a run-in with possible avian flu in 2009 and was falsely diagnosed with ME / CFS. He spent a year wholeheartedly investigating alternative therapies, including yoga, massage, mindfulness and meditation, visualization, talk therapy and more. He never comes across as bitter or sorry for himself. Instead, he considered fatigue a fact of his new life and asked what he could do about it. So this ends up being quite a pleasant amble through the options, some of them more bizarre than others.

Get Well Soon: Adventures in Alternative Healthcare by Nick Duerden: British journalist Nick Duerden had severe post-viral fatigue after a run-in with possible avian flu in 2009 and was falsely diagnosed with ME / CFS. He spent a year wholeheartedly investigating alternative therapies, including yoga, massage, mindfulness and meditation, visualization, talk therapy and more. He never comes across as bitter or sorry for himself. Instead, he considered fatigue a fact of his new life and asked what he could do about it. So this ends up being quite a pleasant amble through the options, some of them more bizarre than others.  *Sight by Jessie Greengrass [skimmed]: I wanted to enjoy this, but ended up frustrated. As a set of themes (losing a parent, choosing motherhood, the ways in which medical science has learned to look into human bodies and minds), it’s appealing; as a novel, it’s off-putting. Had this been presented as a set of autobiographical essays, perhaps I would have loved it. But instead it’s in the coy autofiction mold where you know the author has pulled some observations straight from life, gussied up others, and then, in this case, thrown in a bunch of irrelevant medical material dredged up during research at the Wellcome Library.

*Sight by Jessie Greengrass [skimmed]: I wanted to enjoy this, but ended up frustrated. As a set of themes (losing a parent, choosing motherhood, the ways in which medical science has learned to look into human bodies and minds), it’s appealing; as a novel, it’s off-putting. Had this been presented as a set of autobiographical essays, perhaps I would have loved it. But instead it’s in the coy autofiction mold where you know the author has pulled some observations straight from life, gussied up others, and then, in this case, thrown in a bunch of irrelevant medical material dredged up during research at the Wellcome Library.

*Brainstorm: Detective Stories From the World of Neurology by Suzanne O’Sullivan: Epilepsy affects 600,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide, so it’s an important condition to know about. It is fascinating to see the range of behaviors seizures can be associated with. The guesswork is in determining precisely what is going wrong in the brain, and where, as well as how medicines or surgery could address the fault. “There are still far more unknowns than knowns where the brain is concerned,” O’Sullivan writes; “The brain has a mind of its own,” she wryly adds later on. (O’Sullivan won the Prize in 2016 for It’s All in Your Head.)

*Brainstorm: Detective Stories From the World of Neurology by Suzanne O’Sullivan: Epilepsy affects 600,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide, so it’s an important condition to know about. It is fascinating to see the range of behaviors seizures can be associated with. The guesswork is in determining precisely what is going wrong in the brain, and where, as well as how medicines or surgery could address the fault. “There are still far more unknowns than knowns where the brain is concerned,” O’Sullivan writes; “The brain has a mind of its own,” she wryly adds later on. (O’Sullivan won the Prize in 2016 for It’s All in Your Head.)  I’m also currently reading and enjoying two witty medical books, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris, and Chicken Unga Fever by Phil Whitaker, his collected New Statesman columns on being a GP.

I’m also currently reading and enjoying two witty medical books, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris, and Chicken Unga Fever by Phil Whitaker, his collected New Statesman columns on being a GP. The Beautiful Cure: Harnessing Your Body’s Natural Defences by Daniel M. Davis

The Beautiful Cure: Harnessing Your Body’s Natural Defences by Daniel M. Davis

*Frieda by Annabel Abbs: If you rely only on the words of D.H. Lawrence, you’d think Frieda was lucky to shed a dull family life and embark on an exciting set of bohemian travels with him as he built his name as a writer; Abbs adds nuance to that picture by revealing just how much Frieda was giving up, and the sorrow she left behind her. Frieda’s determination to live according to her own rules makes her a captivating character.

*Frieda by Annabel Abbs: If you rely only on the words of D.H. Lawrence, you’d think Frieda was lucky to shed a dull family life and embark on an exciting set of bohemian travels with him as he built his name as a writer; Abbs adds nuance to that picture by revealing just how much Frieda was giving up, and the sorrow she left behind her. Frieda’s determination to live according to her own rules makes her a captivating character. A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: A delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view before getting Maurice’s own perspective; by this point we know enough to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is.

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: A delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view before getting Maurice’s own perspective; by this point we know enough to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. The Overstory by Richard Powers: A sprawling novel about regular people who through various unpredictable routes become so devoted to trees that they turn to acts, large and small, of civil disobedience to protest the clear-cutting of everything from suburban gardens to redwood forests. I admired pretty much every sentence, whether it’s expository or prophetic.

The Overstory by Richard Powers: A sprawling novel about regular people who through various unpredictable routes become so devoted to trees that they turn to acts, large and small, of civil disobedience to protest the clear-cutting of everything from suburban gardens to redwood forests. I admired pretty much every sentence, whether it’s expository or prophetic. You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld describes families and romantic relationships expertly, in prose so deliciously smooth it slides right down. These 11 stories are about marriage, parenting, authenticity, celebrity and social media in Trump’s America. Overall, this is a whip-smart, current and relatable book, ideal for readers who don’t think they like short stories.

You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld describes families and romantic relationships expertly, in prose so deliciously smooth it slides right down. These 11 stories are about marriage, parenting, authenticity, celebrity and social media in Trump’s America. Overall, this is a whip-smart, current and relatable book, ideal for readers who don’t think they like short stories. *Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson: A charming, bittersweet novel composed entirely of the letters that pass between Tina Hopgood, a 60-year-old farmer’s wife in East Anglia, and Anders Larsen, a curator at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark. It’s a novel about second chances in the second half of life, and has an open but hopeful ending. I found it very touching and wish it hadn’t been given the women’s fiction treatment.

*Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson: A charming, bittersweet novel composed entirely of the letters that pass between Tina Hopgood, a 60-year-old farmer’s wife in East Anglia, and Anders Larsen, a curator at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark. It’s a novel about second chances in the second half of life, and has an open but hopeful ending. I found it very touching and wish it hadn’t been given the women’s fiction treatment. Rough Beauty: Forty Seasons of Mountain Living by Karen Auvinen: An excellent memoir that will have broad appeal with its themes of domestic violence, illness, grief, travel, wilderness, solitude, pets, wildlife, and relationships. A great example of how unchronological autobiographical essays can together build a picture of a life.

Rough Beauty: Forty Seasons of Mountain Living by Karen Auvinen: An excellent memoir that will have broad appeal with its themes of domestic violence, illness, grief, travel, wilderness, solitude, pets, wildlife, and relationships. A great example of how unchronological autobiographical essays can together build a picture of a life. *Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley: Buckley takes readers along on a rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes during four years of chronic pain. I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel.

*Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley: Buckley takes readers along on a rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes during four years of chronic pain. I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel. *This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein: A wry, bittersweet look at the unpredictability of life as an idealistic young woman in the world’s major cities. Another great example of life writing that’s not comprehensive or strictly chronological yet gives a clear sense of the self in the context of a family and in the face of an uncertain future.

*This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein: A wry, bittersweet look at the unpredictability of life as an idealistic young woman in the world’s major cities. Another great example of life writing that’s not comprehensive or strictly chronological yet gives a clear sense of the self in the context of a family and in the face of an uncertain future. *The Pull of the River: Tales of Escape and Adventure on Britain’s Waterways by Matt Gaw: This jolly yet reflective book traces canoe trips down Britain’s rivers, a quest to (re)discover the country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger. Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful.

*The Pull of the River: Tales of Escape and Adventure on Britain’s Waterways by Matt Gaw: This jolly yet reflective book traces canoe trips down Britain’s rivers, a quest to (re)discover the country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger. Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful. The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson: A delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping.

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson: A delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping. *No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol: There was a lot of appeal for me in how MacNicol sets out her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. She is daring and candid in examining her preconceptions and asking what she really wants from her life. And she tells a darn good story: I read this much faster than I generally do with a memoir.

*No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol: There was a lot of appeal for me in how MacNicol sets out her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. She is daring and candid in examining her preconceptions and asking what she really wants from her life. And she tells a darn good story: I read this much faster than I generally do with a memoir. The Library Book by Susan Orlean: This is really two books in one. The first is a record of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library on April 29, 1986 and how the city and library service recovered. The second is a paean to libraries in general: what they offer to society, and how they work, in a digital age. Sure to appeal to any book-lover.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean: This is really two books in one. The first is a record of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library on April 29, 1986 and how the city and library service recovered. The second is a paean to libraries in general: what they offer to society, and how they work, in a digital age. Sure to appeal to any book-lover. Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power: I have a particular weakness for year-challenge books, and Power’s is written in an easy, chatty style, as if Bridget Jones had given over her diary to testing self-help books for 16 months. Help Me! is self-deprecating and relatable, with some sweary Irish swagger thrown in. I can recommend it to self-help junkies and skeptics alike.

Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power: I have a particular weakness for year-challenge books, and Power’s is written in an easy, chatty style, as if Bridget Jones had given over her diary to testing self-help books for 16 months. Help Me! is self-deprecating and relatable, with some sweary Irish swagger thrown in. I can recommend it to self-help junkies and skeptics alike. Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens: Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens: Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive. The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson: Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career. With its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read.

The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson: Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career. With its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read.