Recovery by Gavin Francis: Review and Giveaway

Just over a year ago, I reviewed Dr Gavin Francis’s Intensive Care, his record of the first 10 months of Covid-19, especially as it affected his work as a GP in Scotland. It ended up on my Best of 2021 list and is still the book I point people to for reflections on the pandemic. Recovery serves as a natural sequel: for those contracting Covid, as well as those who have had it before and may be suffering the effects of the long form, the focus will now be on healing as much as it is on preventing the spread of the virus. This lovely little book spins personal and general histories of convalescence, and expresses the hope that our collective brush with death will make us all more determined to treasure our life and wellbeing.

Francis remembers times of recovery in his own life: after meningitis at age 10, falling off his bike at 12, and a sinus surgery during his first year of medical practice. Refuting received wisdom about scammers taking advantage of sickness benefits (government data show only 1.7% of claims are fraudulent), he affirms the importance of a social safety net that allows necessary recovery time. Convalescence is subjective, he notes; it takes as long as it takes, and patients should listen to their bodies and not push too hard out of frustration or boredom.

Traditionally, travel, rest and time in nature have been non-medical recommendations for convalescents, and Francis believes they still hold great value – not least for the positive mental state they promote. He might also employ “social prescribing,” directing his patients to join a club, see a counsellor, get good nutrition or adopt a pet. A recovery period can be as difficult for carers as for patients, he acknowledges, and most of us will spend time as both.

I read this in December while staying with my convalescent mother, and could see how much of its practical advice applied to her – “Plan rests regularly throughout the day,” “Use aids to avoid bending and reaching,” “Set achievable goals.” If only everyone being discharged from hospital could be issued with a copy – pocket-sized and only just over 100 pages, it would be a perfect companion through any recovery period. I’d especially recommend this to readers of Maggie O’Farrell’s I Am, I Am, I Am and Christie Watson’s The Language of Kindness.

Favourite lines:

At one level, convalescence has something in common with dying in that it forces us to engage with our limitations, the fragile nature of our existence. Why not, then, live fully while we can?

If we can take any gifts or wisdom from the experience of illness, surely it’s this: to deepen our appreciation of health … in the knowledge that it can so easily be taken away.

Published by Profile Books/Wellcome Collection today, 13 January. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

*The Profile publicity team has offered a giveaway copy to be sent to one of my readers. If you’d like to be entered in the draw (UK only, sorry), please mention so in your comment below. I’ll choose a winner at random next Friday morning (the 21st) and contact them by e-mail.*

Being the Expert for #NonficNov / Three on a Theme: “Care”

The Being/Becoming/Asking the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Rennie of What’s Nonfiction. This is my second entry for the week after Monday’s post on postpartum depression, as well as the second installment in my new “Three on a Theme” series, where I review three books that have something significant in common and tell you which one to pick up if you want to read into the topic for yourself.

It will be no surprise to regular readers that both of my ‘expert’ posts have been on a health theme: I have an amateur’s love of medical memoirs and works of medical history, and I’ve followed the Wellcome Book Prize closely for a number of years – participating in official blog tours, creating a shadow panel, and running this past year’s Not the Wellcome Prize.

The three books below are linked by the word “Care” in the title or subtitle; all reflect, in the wake of COVID-19, on the ongoing crisis in UK healthcare and the vital role of nurses.

Labours of Love: The Crisis of Care by Madeleine Bunting

Bunting’s previous nonfiction work could hardly be more different: Love of Country was a travel memoir about the Scottish Hebrides. It was the first book I finished reading in 2017, and there could have been no better start to a year’s reading. With a background in history, journalism and politics, the author is well placed to comment on current events. Labours of Love arose from five years of travel to healthcare settings across the UK: care homes for the elderly and disabled, hospitals, local doctors’ surgeries, and palliative care units. Forget the Thursday-night clapping and rainbows in the windows: the NHS is perennially underfunded and its staff undervalued, by conservative governments as well as by people who rely on it.

Bunting’s previous nonfiction work could hardly be more different: Love of Country was a travel memoir about the Scottish Hebrides. It was the first book I finished reading in 2017, and there could have been no better start to a year’s reading. With a background in history, journalism and politics, the author is well placed to comment on current events. Labours of Love arose from five years of travel to healthcare settings across the UK: care homes for the elderly and disabled, hospitals, local doctors’ surgeries, and palliative care units. Forget the Thursday-night clapping and rainbows in the windows: the NHS is perennially underfunded and its staff undervalued, by conservative governments as well as by people who rely on it.

We first experience bodily care as infants, Bunting notes, and many of the questions that run through her book originated in her early days of motherhood. Despite all the advances of feminism, parental duties follow the female-dominated pattern evident in the caring careers:

By the age of fifty-nine, women will have a fifty-fifty chance of being, or having been, a carer for a sick or elderly person. At the same time, many are still raising their teenage children and almost half of those over fifty-five are providing regular care for grandchildren.

Women dominate caring professions such as nursing (89 per cent), social work (75 per cent) and childcare (98 per cent). They now form the majority of GPs (54 per cent) and three out of four teachers are female. And they provide the vast bulk of the army of healthcare workers in the NHS (80 per cent) and social-care workers (82 per cent) for the long-term sick, disabled and frail elderly.

These are things we know intuitively, but seeing the numbers laid out so plainly is shocking. I most valued the general information in Bunting’s introduction and in between her interviews, while I found that the bulk of the book alternated between dry statistics and page after page of interview transcripts. However, I did love hearing more from Marion Coutts, the author of the 2015 Wellcome Book Prize winner, The Iceberg, about her husband’s death from brain cancer. (Labours of Love was longlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction 2020.)

My thanks to Granta for the free copy for review.

Duty of Care: One NHS Doctor’s Story of Courage and Compassion on the COVID-19 Frontline by Dr Dominic Pimenta

We’re going to see a flood of such books; I’m most looking forward to Dr Rachel Clarke’s Breathtaking (coming in January). Given how long it takes to get a book from manuscript to published product, I was impressed to find this on my library’s Bestsellers shelf in October. Pimenta’s was an early voice warning of the scale of the crisis and the government’s lack of preparation. He focuses on a narrow window of time, from February – when he encountered his first apparent case of coronavirus – to May, when, in protest at a government official flouting lockdown (readers outside the UK might not be familiar with the Cummings affair), he resigned his cardiology job at a London hospital to focus on his new charity, HEROES, which supports healthcare workers via PPE, childcare grants, mental health help and so on.

We’re going to see a flood of such books; I’m most looking forward to Dr Rachel Clarke’s Breathtaking (coming in January). Given how long it takes to get a book from manuscript to published product, I was impressed to find this on my library’s Bestsellers shelf in October. Pimenta’s was an early voice warning of the scale of the crisis and the government’s lack of preparation. He focuses on a narrow window of time, from February – when he encountered his first apparent case of coronavirus – to May, when, in protest at a government official flouting lockdown (readers outside the UK might not be familiar with the Cummings affair), he resigned his cardiology job at a London hospital to focus on his new charity, HEROES, which supports healthcare workers via PPE, childcare grants, mental health help and so on.

It felt uncanny to be watching events from earlier in the year unfold again: so clearly on a trajectory to disaster, but still gripping in the telling. Pimenta’s recreated dialogue and scenes are excellent. He gives a real sense of the challenges in his personal and professional lives. But I think I’d like a little more distance before I read this in entirety. Just from my skim, I know that it’s a very fluid book that reads almost like a thriller, and it ends with a sober but sensible statement of the situation we face. (All royalties from the book go to HEROES.)

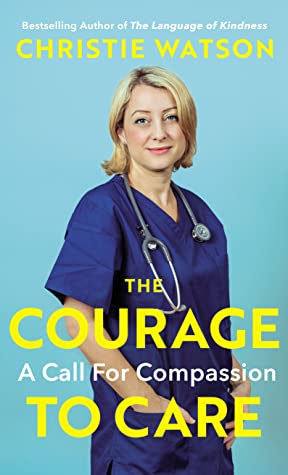

The Courage to Care: A Call for Compassion by Christie Watson

I worried this would be a dull work of polemic; perhaps the title, though stirring, is inapt, as the book is actually a straightforward sequel to Watson’s 2018 memoir about being a nurse, The Language of Kindness. Although, like Bunting, Watson traveled widely to research the state of care in the country, she mostly relies on her own experience of various nursing settings over two decades: a pediatric intensive care unit, home healthcare for the elderly, a children’s oncology day center, a residential home for those with severe physical and learning disabilities, a community mental-health visiting team, and the emergency room. She also shadows military nurses and prison doctors.

I worried this would be a dull work of polemic; perhaps the title, though stirring, is inapt, as the book is actually a straightforward sequel to Watson’s 2018 memoir about being a nurse, The Language of Kindness. Although, like Bunting, Watson traveled widely to research the state of care in the country, she mostly relies on her own experience of various nursing settings over two decades: a pediatric intensive care unit, home healthcare for the elderly, a children’s oncology day center, a residential home for those with severe physical and learning disabilities, a community mental-health visiting team, and the emergency room. She also shadows military nurses and prison doctors.

With a novelist’s talent for scene-setting and characterization, Watson weaves each patient and incident into a vibrant story. Another strand is about parenthood: giving birth to her daughter and the process of adopting her son – both are now teenagers she raises as a single mother. She affirms the value of everyday care delivered by parents and nurses alike. I was especially struck by the account of a teenage girl who contracted measles (then pneumonia, meningitis and encephalitis) and was left blind and profoundly disabled, all because her parents were antivaxxers. In general, I’ve wearied of doctors’ memoirs composed of obviously anonymized case studies, but I’ll always make an exception for Clarke and Watson because of their gorgeous writing.

Note: Watson had left nursing to write full-time, but explains in an afterword that she returned to critical care in a London hospital during COVID-19.

What I learned:

Empathy is a key term for all three authors. They emphasize that the skills of compassion and listening are just as important as the ability to perform the required medical procedures.

A chilling specific fact I learned: 43,000 people died in the Blitz* in the UK. Pimenta cited that figure and warned that COVID-19 could be worse. And indeed, as of now, over 63,000 people have died of COVID-19 in the UK. The American death toll is even more alarming.

Here are some passages that stood out for me from each book:

Bunting: “Good care is as much an art as a skill, as much competence as tact. … Care is where we make profound collective decisions about the worth of an individual life. … There is no tradition of ageing wisely in the West, unlike in many Asian and African cultures where age has prestige, status and is associated with wisdom … We need to speak about care in a different language, instead of the relentless macho repetition of words such as ‘efficiency’, ‘quality’, ‘driving’, ‘choice’, ‘delivery’ and productivity.’”

Pimenta: “this will be akin to the Blitz*, and … we need to start thinking of it like that. A marathon, not a sprint. … The challenges to come – a second or even third wave, a global recession, climate change, mass misinformation … and political and societal upheaval … – will all require more from all of us if we hope to meet them. The challenge of our generation is not behind us, it is only just beginning. I plan to continue doing something about it, and perhaps now you do as well. So stay informed, stay safe and be kind.”

Watson: “So much of nursing, I think to myself, seems obvious, and yet seeing that need in the first place is difficult and takes experience, training and something extra. … The mundanity of human existence is where I find the most beauty … It takes my breath away: how fragile, extraordinary and vulnerable, how full of hatred and love and obsession and complexity we all are – every single one of us.”

*I highly recommend all of folk artist Kris Drever’s latest album, Where the World Is Thin, but especially the song “Hunker Down / That Old Blitz Spirit,” which has become my lockdown anthem.

If you read just one, though… Make it The Courage to Care by Christie Watson.

Can you see yourself reading any of these books?

Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard

“For fans of Adam Kay’s This Is Going to Hurt and Christie Watson’s The Language of Kindness,” the blurb on my press release for Leah Hazard’s memoir opens. The publisher’s comparisons couldn’t be more perfect: Hard Pushed has the gynecological detail and edgy sense of humor of Kay’s book (“Another night, another vagina” is its first line, and the author has been known to introduce herself with “Midwife Hazard, at your cervix!”), and matches Watson’s with its empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout.

Hazard alternates between anonymized case studies of patients she has treated and general thoughts on her chosen career (e.g. “Notes on Triage” and “Notes on Being from Somewhere Else”). Although all of the patients in her book are fictional composites, their circumstances are rendered so vividly that you quickly forget these particular characters never existed. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room with Eleanor, one-half of a lesbian couple welcoming a child thanks to the now-everyday wonder of IVF; Hawa, a Somali woman whose pregnancy is complicated by the genital mutilation she underwent as a child; and Pei Hsuan, a Chinese teenager who was trafficked into sex work in Britain.

Sometimes we don’t learn the endings to these stories. Will 15-year-old Crystal have a healthy baby after she starts leaking fluid at 23 weeks? What will happen next for Pei Hsuan after her case is passed on to refugee services? Hazard deliberately leaves things uncertain to reflect the partial knowledge a hospital midwife often has of her patients: they’re taken off to surgery or discharged, and when they eventually come back to deliver someone else may be on duty. All she can do is to help each woman the best she can in the moment.

A number of these cases allow the author to comment on the range of modern opinions about pregnancy and childrearing, including some controversies. A pushy new grandmother tries to pressure her daughter into breastfeeding; a woman struggles with her mental health while on maternity leave; a rape victim is too far along to have a termination. At the other end of the spectrum, we meet a hippie couple in a birthing pool who prefer to speak of “surges” rather than contractions. Hazard rightly contends that it’s not her place to cast judgment on any of her patients’ decisions; her job is simply to deal with the situation at hand.

A number of these cases allow the author to comment on the range of modern opinions about pregnancy and childrearing, including some controversies. A pushy new grandmother tries to pressure her daughter into breastfeeding; a woman struggles with her mental health while on maternity leave; a rape victim is too far along to have a termination. At the other end of the spectrum, we meet a hippie couple in a birthing pool who prefer to speak of “surges” rather than contractions. Hazard rightly contends that it’s not her place to cast judgment on any of her patients’ decisions; her job is simply to deal with the situation at hand.

I especially liked reading about the habits that keep the author going through long overnight shifts, such as breaking the time up into 15-minute increments, each with its own assigned task. The excerpts from her official notes – in italics and full of shorthand and jargon – are a neat window into the science and reality of a midwife’s work, with a glossary at the end of the book ensuring that nothing is too technical for laypeople.

Hazard, an American, lives in Scotland and has a Glaswegian husband and two daughters. Her experience of being an NHS midwife has not always been ideal; there were even moments when she was ready to quit. Like Kay and Watson, she has found that the medical field can be unforgiving what with low pay, little recognition and hardly any time to wolf down your dinner during a break, let alone reflect on the life-and-death situations you’ve been a part of. Yet its rewards outweigh the downsides.

Hard Pushed has none of the sentimentality of Call the Midwife – a relief since I’m not one to gush over babies. Still, it’s a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering. If you like books that follow doctors and nurses down hospital hallways, you’ll love it. This was one of my most anticipated books of the first half of the year, and it lived up to my expectations. It’s also one of my top contenders for the 2020 Wellcome Book Prize so far.

A few favorite passages:

“So many things in midwifery are ‘wee’ [in Scotland, at least!] – a wee cut, a wee tear, a wee bleed, the latter used to describe anything from a trickle to a torrent. Euphemisms are one of our many small mercies: we learn early on to downplay and dissemble. The brutality of birth is often self-evident; there is little need to elaborate.”

“Whenever I dress a wound in this way, I remember that this is an act of loving validation; every wound tells a story, and every dressing is an acknowledgement of that story – the midwife’s way of saying, I hear you, and I believe you.”

“midwives do so much more than catch babies. We devise and implement plans of care; we connect, console, empathise and cheerlead; we prescribe; we do minor surgery. … We may never have met you until the day we ride into battle for you and your baby; … you may not even recognise the cavalry that’s been at your back until the drapes are down and the blood has dried beneath your feet.”

My rating:

Hard Pushed was published in the UK on May 2nd (just a few days before International Midwives’ Day) by Hutchinson. My thanks to the publisher for the free proof copy for review.

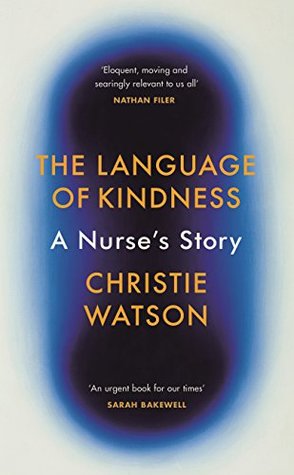

The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson

After all that Wellcome Book Prize reading, I’ve given myself a break from the medical reads, right? No way! I’m already eagerly looking out for hopefuls for next year’s prize – I’ve amassed quite a nice little pile – and this is a particularly strong candidate, based on the 20 years that Watson spent as a nurse in England’s health system before leaving to write full-time. (Her debut, Tiny Sunbirds Far Away, won the Costa First Novel Award in 2011; she followed it up with Where Women Are Kings in 2013.) It taps into the widespread feeling that medicine is in desperate need of a good dose of compassion, and will ring true for anyone who spends time in hospitals, whether as a patient or a carer.

Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career, as she grows from a seventeen-year-old trainee who’s squeamish about blood to a broadly experienced nurse who can hardly be fazed by anything. The first chapter is set up like a tour of the hospital, describing everything she sees and hears as she makes her way up to her office, and the final chapter takes place on her very last day as a nurse, when, faced with a laboring mother in a taxi, she has to deliver the baby right there in the carpark.

Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career, as she grows from a seventeen-year-old trainee who’s squeamish about blood to a broadly experienced nurse who can hardly be fazed by anything. The first chapter is set up like a tour of the hospital, describing everything she sees and hears as she makes her way up to her office, and the final chapter takes place on her very last day as a nurse, when, faced with a laboring mother in a taxi, she has to deliver the baby right there in the carpark.

In between we hear a series of vivid stories that veer between heartwarming and desperately sad. Watson sees children given a second shot at life. Aaron gets a heart–lung transplant to treat his cystic fibrosis and two-year-old Charlotte bounces back from sepsis – though with prosthetic limbs. But she also sees the ones who won’t get better: Tia, a little girl with a brain tumor; Mahesh, who has muscular dystrophy and relies on a breathing tube; and Jasmin, who is brought to the hospital after a house fire but doesn’t survive for long. She dies in the nurses’ arms as they’re washing the smoke smell out of her hair.

Although Watson specialized in children’s intensive care nursing, she trained in all branches of nursing, so we follow her into the delivery room, mental health ward, and operating theatre. As in Maggie O’Farrell’s I Am, I Am, I Am, we learn about her links to hospitals over the years, starting with her memories of being nursed as a child. She met her former partner, a consultant, at the hospital; they had a child together and adopted another before splitting 12 years later. And as her father was dying of lung cancer, she developed a new appreciation for what nurses do as she observed the dedicated care he received from his hospice nurse. She characterizes nursing as a career that requires great energy, skill and emotional intelligence, “that demands a chunk of your soul on a daily basis,” yet is all too often undervalued.

(The superior American cover.)

For me the weakest sections of Watson’s book are the snippets of history about hospitals and the development of the theory and philosophy of nursing. These insertions feel a little awkward and break up the flow of personal disclosure. The same applies to the occasional parenthetical phrase that seems to talk down to the reader, such as “women now receive medical help (IVF) to have their babies” and “obstetricians (doctors) run the show.” Footnotes or endnotes connected to a short glossary might have been a less obtrusive way of adding such explanatory information.

I would particularly recommend this memoir to readers of Kathryn Mannix’s With the End in Mind and Henry Marsh’s Admissions. But with its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read. I have it on good authority that there has recently been a copy on the desk of Jeremy Hunt, Health Secretary of the UK, which seems like an awfully good start.

A few favorite passages:

“I wanted to live many lives, to experience different ways of living. I didn’t know then that I would find exactly what I searched for: that both nursing and writing are about stepping into other shoes all the time.”

“What I thought nursing involved when I started: chemistry, biology, physics, pharmacology and anatomy. And what I now know to be the truth of nursing: philosophy, psychology, art, ethics and politics.”

“You get used to all sorts of smells, as a nurse. [An amazingly graphic passage!] But for all that I’ve seen and touched and smelled, and as difficult as it is at the time, there is a patient at the centre of it, afraid and embarrassed. … The horror of our bodies – our humanity, our flesh and blood – is something nurses must bear, lest the patient think too deeply, remember the lack of dignity that makes us all vulnerable. It is our vulnerability that unites us. Promoting dignity in the face of illness is one of the best gifts a nurse can give.”

My rating:

The Language of Kindness was published in the UK on May 3rd by Chatto & Windus. My thanks to the publisher for the free review copy. It is released today, May 8th, by Doubleday Canada and Tim Duggan Books in the States.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

In Shock by Rana Awdish: The doctor became the patient when Awdish, seven months pregnant, was rushed into emergency surgery with excruciating pain due to severe hemorrhaging into the space around her liver, later explained by a ruptured tumor. Having experienced brusque, cursory treatment, even from colleagues at her Detroit-area hospital, she was convinced that doctors needed to do better. This memoir is a gripping story of her own medical journey and a fervent plea for compassion from medical professionals.

In Shock by Rana Awdish: The doctor became the patient when Awdish, seven months pregnant, was rushed into emergency surgery with excruciating pain due to severe hemorrhaging into the space around her liver, later explained by a ruptured tumor. Having experienced brusque, cursory treatment, even from colleagues at her Detroit-area hospital, she was convinced that doctors needed to do better. This memoir is a gripping story of her own medical journey and a fervent plea for compassion from medical professionals.  Doctor by Andrew Bomback: Part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, this is a wide-ranging look at what it’s like to be a doctor. Bomback is a kidney specialist; his wife is also a doctor, and his father, fast approaching retirement, is the kind of old-fashioned, reassuring pediatrician who knows everything. Even the author’s young daughter likes playing with a stethoscope and deciding what’s wrong with her dolls. In a sense, then, Bomback uses fragments of family memoir to compare the past, present and likely future of medicine.

Doctor by Andrew Bomback: Part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, this is a wide-ranging look at what it’s like to be a doctor. Bomback is a kidney specialist; his wife is also a doctor, and his father, fast approaching retirement, is the kind of old-fashioned, reassuring pediatrician who knows everything. Even the author’s young daughter likes playing with a stethoscope and deciding what’s wrong with her dolls. In a sense, then, Bomback uses fragments of family memoir to compare the past, present and likely future of medicine.  A Moment of Grace by Patrick Dillon [skimmed]: A touching short memoir of the last year of his wife Nicola Thorold’s life, in which she battled acute myeloid leukemia. Dillon doesn’t shy away from the pain and difficulties, but is also able to summon up some gratitude.

A Moment of Grace by Patrick Dillon [skimmed]: A touching short memoir of the last year of his wife Nicola Thorold’s life, in which she battled acute myeloid leukemia. Dillon doesn’t shy away from the pain and difficulties, but is also able to summon up some gratitude.  Get Well Soon: Adventures in Alternative Healthcare by Nick Duerden: British journalist Nick Duerden had severe post-viral fatigue after a run-in with possible avian flu in 2009 and was falsely diagnosed with ME / CFS. He spent a year wholeheartedly investigating alternative therapies, including yoga, massage, mindfulness and meditation, visualization, talk therapy and more. He never comes across as bitter or sorry for himself. Instead, he considered fatigue a fact of his new life and asked what he could do about it. So this ends up being quite a pleasant amble through the options, some of them more bizarre than others.

Get Well Soon: Adventures in Alternative Healthcare by Nick Duerden: British journalist Nick Duerden had severe post-viral fatigue after a run-in with possible avian flu in 2009 and was falsely diagnosed with ME / CFS. He spent a year wholeheartedly investigating alternative therapies, including yoga, massage, mindfulness and meditation, visualization, talk therapy and more. He never comes across as bitter or sorry for himself. Instead, he considered fatigue a fact of his new life and asked what he could do about it. So this ends up being quite a pleasant amble through the options, some of them more bizarre than others.  *Sight by Jessie Greengrass [skimmed]: I wanted to enjoy this, but ended up frustrated. As a set of themes (losing a parent, choosing motherhood, the ways in which medical science has learned to look into human bodies and minds), it’s appealing; as a novel, it’s off-putting. Had this been presented as a set of autobiographical essays, perhaps I would have loved it. But instead it’s in the coy autofiction mold where you know the author has pulled some observations straight from life, gussied up others, and then, in this case, thrown in a bunch of irrelevant medical material dredged up during research at the Wellcome Library.

*Sight by Jessie Greengrass [skimmed]: I wanted to enjoy this, but ended up frustrated. As a set of themes (losing a parent, choosing motherhood, the ways in which medical science has learned to look into human bodies and minds), it’s appealing; as a novel, it’s off-putting. Had this been presented as a set of autobiographical essays, perhaps I would have loved it. But instead it’s in the coy autofiction mold where you know the author has pulled some observations straight from life, gussied up others, and then, in this case, thrown in a bunch of irrelevant medical material dredged up during research at the Wellcome Library.

*Brainstorm: Detective Stories From the World of Neurology by Suzanne O’Sullivan: Epilepsy affects 600,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide, so it’s an important condition to know about. It is fascinating to see the range of behaviors seizures can be associated with. The guesswork is in determining precisely what is going wrong in the brain, and where, as well as how medicines or surgery could address the fault. “There are still far more unknowns than knowns where the brain is concerned,” O’Sullivan writes; “The brain has a mind of its own,” she wryly adds later on. (O’Sullivan won the Prize in 2016 for It’s All in Your Head.)

*Brainstorm: Detective Stories From the World of Neurology by Suzanne O’Sullivan: Epilepsy affects 600,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide, so it’s an important condition to know about. It is fascinating to see the range of behaviors seizures can be associated with. The guesswork is in determining precisely what is going wrong in the brain, and where, as well as how medicines or surgery could address the fault. “There are still far more unknowns than knowns where the brain is concerned,” O’Sullivan writes; “The brain has a mind of its own,” she wryly adds later on. (O’Sullivan won the Prize in 2016 for It’s All in Your Head.)  I’m also currently reading and enjoying two witty medical books, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris, and Chicken Unga Fever by Phil Whitaker, his collected New Statesman columns on being a GP.

I’m also currently reading and enjoying two witty medical books, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris, and Chicken Unga Fever by Phil Whitaker, his collected New Statesman columns on being a GP. The Beautiful Cure: Harnessing Your Body’s Natural Defences by Daniel M. Davis

The Beautiful Cure: Harnessing Your Body’s Natural Defences by Daniel M. Davis

*Frieda by Annabel Abbs: If you rely only on the words of D.H. Lawrence, you’d think Frieda was lucky to shed a dull family life and embark on an exciting set of bohemian travels with him as he built his name as a writer; Abbs adds nuance to that picture by revealing just how much Frieda was giving up, and the sorrow she left behind her. Frieda’s determination to live according to her own rules makes her a captivating character.

*Frieda by Annabel Abbs: If you rely only on the words of D.H. Lawrence, you’d think Frieda was lucky to shed a dull family life and embark on an exciting set of bohemian travels with him as he built his name as a writer; Abbs adds nuance to that picture by revealing just how much Frieda was giving up, and the sorrow she left behind her. Frieda’s determination to live according to her own rules makes her a captivating character. A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: A delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view before getting Maurice’s own perspective; by this point we know enough to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is.

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: A delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view before getting Maurice’s own perspective; by this point we know enough to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. The Overstory by Richard Powers: A sprawling novel about regular people who through various unpredictable routes become so devoted to trees that they turn to acts, large and small, of civil disobedience to protest the clear-cutting of everything from suburban gardens to redwood forests. I admired pretty much every sentence, whether it’s expository or prophetic.

The Overstory by Richard Powers: A sprawling novel about regular people who through various unpredictable routes become so devoted to trees that they turn to acts, large and small, of civil disobedience to protest the clear-cutting of everything from suburban gardens to redwood forests. I admired pretty much every sentence, whether it’s expository or prophetic. You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld describes families and romantic relationships expertly, in prose so deliciously smooth it slides right down. These 11 stories are about marriage, parenting, authenticity, celebrity and social media in Trump’s America. Overall, this is a whip-smart, current and relatable book, ideal for readers who don’t think they like short stories.

You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld describes families and romantic relationships expertly, in prose so deliciously smooth it slides right down. These 11 stories are about marriage, parenting, authenticity, celebrity and social media in Trump’s America. Overall, this is a whip-smart, current and relatable book, ideal for readers who don’t think they like short stories. *Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson: A charming, bittersweet novel composed entirely of the letters that pass between Tina Hopgood, a 60-year-old farmer’s wife in East Anglia, and Anders Larsen, a curator at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark. It’s a novel about second chances in the second half of life, and has an open but hopeful ending. I found it very touching and wish it hadn’t been given the women’s fiction treatment.

*Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson: A charming, bittersweet novel composed entirely of the letters that pass between Tina Hopgood, a 60-year-old farmer’s wife in East Anglia, and Anders Larsen, a curator at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark. It’s a novel about second chances in the second half of life, and has an open but hopeful ending. I found it very touching and wish it hadn’t been given the women’s fiction treatment. Rough Beauty: Forty Seasons of Mountain Living by Karen Auvinen: An excellent memoir that will have broad appeal with its themes of domestic violence, illness, grief, travel, wilderness, solitude, pets, wildlife, and relationships. A great example of how unchronological autobiographical essays can together build a picture of a life.

Rough Beauty: Forty Seasons of Mountain Living by Karen Auvinen: An excellent memoir that will have broad appeal with its themes of domestic violence, illness, grief, travel, wilderness, solitude, pets, wildlife, and relationships. A great example of how unchronological autobiographical essays can together build a picture of a life. *Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley: Buckley takes readers along on a rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes during four years of chronic pain. I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel.

*Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley: Buckley takes readers along on a rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes during four years of chronic pain. I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel. *This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein: A wry, bittersweet look at the unpredictability of life as an idealistic young woman in the world’s major cities. Another great example of life writing that’s not comprehensive or strictly chronological yet gives a clear sense of the self in the context of a family and in the face of an uncertain future.

*This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein: A wry, bittersweet look at the unpredictability of life as an idealistic young woman in the world’s major cities. Another great example of life writing that’s not comprehensive or strictly chronological yet gives a clear sense of the self in the context of a family and in the face of an uncertain future. *The Pull of the River: Tales of Escape and Adventure on Britain’s Waterways by Matt Gaw: This jolly yet reflective book traces canoe trips down Britain’s rivers, a quest to (re)discover the country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger. Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful.

*The Pull of the River: Tales of Escape and Adventure on Britain’s Waterways by Matt Gaw: This jolly yet reflective book traces canoe trips down Britain’s rivers, a quest to (re)discover the country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger. Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful. The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson: A delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping.

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson: A delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping. *No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol: There was a lot of appeal for me in how MacNicol sets out her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. She is daring and candid in examining her preconceptions and asking what she really wants from her life. And she tells a darn good story: I read this much faster than I generally do with a memoir.

*No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol: There was a lot of appeal for me in how MacNicol sets out her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. She is daring and candid in examining her preconceptions and asking what she really wants from her life. And she tells a darn good story: I read this much faster than I generally do with a memoir. The Library Book by Susan Orlean: This is really two books in one. The first is a record of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library on April 29, 1986 and how the city and library service recovered. The second is a paean to libraries in general: what they offer to society, and how they work, in a digital age. Sure to appeal to any book-lover.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean: This is really two books in one. The first is a record of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library on April 29, 1986 and how the city and library service recovered. The second is a paean to libraries in general: what they offer to society, and how they work, in a digital age. Sure to appeal to any book-lover. Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power: I have a particular weakness for year-challenge books, and Power’s is written in an easy, chatty style, as if Bridget Jones had given over her diary to testing self-help books for 16 months. Help Me! is self-deprecating and relatable, with some sweary Irish swagger thrown in. I can recommend it to self-help junkies and skeptics alike.

Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power: I have a particular weakness for year-challenge books, and Power’s is written in an easy, chatty style, as if Bridget Jones had given over her diary to testing self-help books for 16 months. Help Me! is self-deprecating and relatable, with some sweary Irish swagger thrown in. I can recommend it to self-help junkies and skeptics alike. Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens: Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens: Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive. The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson: Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career. With its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read.

The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson: Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career. With its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read.