Re-Reading Modern Classics: Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” Series

I didn’t manage a traditional classic this month: I stalled on Cider with Rosie and gave up on Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust after just 16 pages. Instead, I’m highlighting three books from Fiction Advocate’s new series about re-reading modern classics, “…Afterwords.” Their tagline is “Essential Readings of the New Canon,” and the concept is to have “acclaimed writers investigate the contemporary classics.”

As Italo Calvino notes in his invaluable essay “Why Read the Classics?”, “The classics are those books about which you usually hear people saying: ‘I’m rereading…’, never ‘I’m reading…’.” Harold Bloom agrees in The Western Canon: “One ancient test for the canonical remains fiercely valid: unless it demands rereading, the work does not qualify.” But readers will also encounter books that strike such a chord with them that they become personal classics. Calvino exhorts readers that “during unenforced reading … you will come across the book which will become ‘your’ book…‘Your’ classic is a book to which you cannot remain indifferent, and which helps you define yourself in relation or even in opposition to it.”

For the Afterwords series, the three writers below have each chosen a modern classic that they can’t stop reading for all it has to say to their own situation and on humanity in general.

I Meant to Kill Ye: Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian by Stephanie Reents (2018)

Blood Meridian must be one of the two or three bleakest books I’ve ever read. I was led to it by Bloom, who speaks about it as a, if not the, Great American Novel. It’s over 10 years since I’ve read it now, but I still remember some of the specific incidences of violence, like skewering babies and sodomizing corpses on a battlefield, as well as the overall feeling of nihilism: there’s no reason for the evil promulgated by characters like the Judge; it is simply a reality – perhaps the human condition.

Reents, who teaches English at the College of the Holy Cross, returns to Blood Meridian, a novel she has re-read compulsively over the years, to ask why it continues to have such a hold over her. Its third-person perspective is so distant that we never understand characters’ motivations or glimpse their inner lives, she notes; everyone seems like a pawn in a fated course. She usually shies away from violence and long descriptive passages; she has an uneasy relationship with the West, having moved away from Idaho to live on the East coast. So why should this detached, brutal Western based on the Glanton Gang’s Mexico/Texas killing spree have so captivated her? “Often, we most admire the books that we could never produce, the writing styles or intellects so different from our own that we aren’t even tempted to try imitating them,” she offers as explanation. “It’s a pure kind of admiration, unsullied by envy.” (I feel that way about Faulkner and Steinbeck.)

Reents, who teaches English at the College of the Holy Cross, returns to Blood Meridian, a novel she has re-read compulsively over the years, to ask why it continues to have such a hold over her. Its third-person perspective is so distant that we never understand characters’ motivations or glimpse their inner lives, she notes; everyone seems like a pawn in a fated course. She usually shies away from violence and long descriptive passages; she has an uneasy relationship with the West, having moved away from Idaho to live on the East coast. So why should this detached, brutal Western based on the Glanton Gang’s Mexico/Texas killing spree have so captivated her? “Often, we most admire the books that we could never produce, the writing styles or intellects so different from our own that we aren’t even tempted to try imitating them,” she offers as explanation. “It’s a pure kind of admiration, unsullied by envy.” (I feel that way about Faulkner and Steinbeck.)

As part of her quest, Reents recreated some of the Gang’s desert route and traveled to the Texas State University library near Austin to look at McCarthy’s early drafts, notes and correspondence. She was intrigued to learn that the Kid was a more conventional POV character to start with, and McCarthy initially included more foreshadowing. By cutting all of it, he made it so that the book’s extreme violence comes out of nowhere. Reents also explores the historical basis for the story via General Samuel Chamberlain’s dubious memoir. Pondering the volatility of the human heart as she drives along the Mexican border, she ends on the nicely timely note of a threatened Trump-built wall. I doubt I could stomach reading Blood Meridian again (though I’ve read another two McCarthy novels since), but I enjoyed revisiting it with Reents as she finds herself “re-bewildered by its beauty and horror.”

A Little in Love with Everyone: Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home by Genevieve Hudson (2018)

Alison Bechdel is one of Hudson’s queer heroes (along with James Baldwin, Tracy Chapman, and seven others), portrayed opposite the first page of each chapter in black and white drawings by Pace Taylor – the sort of people who gave her the courage to accept her lesbian identity after a conventional Alabama upbringing.

As portrayed in her landmark graphic memoir Fun Home, Bechdel was in college and finally coming to terms with her sexuality at the same time that she learned that her father was gay and her parents were about to divorce. Her father died in an accident just a few months later and, though he had many affairs, had never managed to live out his homosexuality openly. As Bechdel’s mother scoffed, “Your father tell the truth? Please!” By contrast, Hudson appreciates Bechdel so much because of her hard-won honesty: “In her work, Bechdel does the opposite of lying. She excavates the real. She dredges up the stuff of her life, embarrassing parts and all.”

As portrayed in her landmark graphic memoir Fun Home, Bechdel was in college and finally coming to terms with her sexuality at the same time that she learned that her father was gay and her parents were about to divorce. Her father died in an accident just a few months later and, though he had many affairs, had never managed to live out his homosexuality openly. As Bechdel’s mother scoffed, “Your father tell the truth? Please!” By contrast, Hudson appreciates Bechdel so much because of her hard-won honesty: “In her work, Bechdel does the opposite of lying. She excavates the real. She dredges up the stuff of her life, embarrassing parts and all.”

Hudson looks at how people craft their own coming-out narratives, the importance of which cannot be overemphasized, in her experience. “Coming out was a tangible thing with tangible effects. For every friend who left my life, a new person arrived—usually someone with broader horizons, exciting stories, and a deviance that seemed sweet and sexy and sincere. After I came out, roaming the streets of Charleston in fat sunglasses and thin dresses, a group of beautiful lesbians appeared out of nowhere. … Everyone was a little in love with everyone.”

A Cool Customer: Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking by Jacob Bacharach (2018)

I made the mistake of not taking any notes on, or even marking out any favorite passages in, this, so all I can tell you is that for me it was the most powerful of the three I’ve tried from the series. The author re-examines Didion’s work in the light of his own encounter with loss – his brother’s death from a drug overdose – and ponders why it has become such a watershed in bereavement literature. Didion really is the patron saint of grief thanks to her two memoirs, Magical Thinking and Blue Nights – after she was widowed she also lost her only daughter – even though she writes with a sort of intellectual detachment; you have to intuit the emotion between the lines. Bacharach smartly weaves his family story with a literate discussion of Didion’s narratives and cultural position to make a snappy and inviting book you could easily read in one sitting.

I made the mistake of not taking any notes on, or even marking out any favorite passages in, this, so all I can tell you is that for me it was the most powerful of the three I’ve tried from the series. The author re-examines Didion’s work in the light of his own encounter with loss – his brother’s death from a drug overdose – and ponders why it has become such a watershed in bereavement literature. Didion really is the patron saint of grief thanks to her two memoirs, Magical Thinking and Blue Nights – after she was widowed she also lost her only daughter – even though she writes with a sort of intellectual detachment; you have to intuit the emotion between the lines. Bacharach smartly weaves his family story with a literate discussion of Didion’s narratives and cultural position to make a snappy and inviting book you could easily read in one sitting.

Indeed, all of the Afterwords books are 120–160-page, small-format paperbacks that would handily slip into a pocket or purse.

My thanks to the publisher for the free copies for review.

The other titles in the series are An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom by Jonathan Russell Clark (on 2666 by Roberto Bolaño), New Uses for Failure by Adam Colman (on 10:04 by Ben Lerner, and Bizarro Worlds by Stacie Williams (on The Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem).

Next month’s plan: The Leopard by Giuseppe di Lampedusa will be my classic to get me in the mood for traveling to Italy for the first week of July.

To my disappointment, I find I can’t make generalizations about the correlation between a book’s page count and its quality: a great book stands out no matter its length. But as Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) said of his latest work, a set of four short novels, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” Three of the five I review today definitely meet those criteria, impressing me with the literal and/or emotional ground covered.

To my disappointment, I find I can’t make generalizations about the correlation between a book’s page count and its quality: a great book stands out no matter its length. But as Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) said of his latest work, a set of four short novels, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” Three of the five I review today definitely meet those criteria, impressing me with the literal and/or emotional ground covered.

Pierre Arthens, France’s most formidable food critic, is on his deathbed reliving his most memorable meals and searching for one elusive flavor to experience again before he dies. He’s proud of his accomplishments – “I have covered the entire range of culinary art, for I am an encyclopedic esthete who is always one dish ahead of the game” – and expresses no remorse for his affairs and his coldness as a father. This takes place in the same apartment building as The Elegance of the Hedgehog and is in short first-person chapters narrated by various figures from Arthens’ life. His wife, his children and his doctor are expected, but we also hear from the building’s concierge, a homeless man he passed every day for ten years, and even a sculpture in his study. I liked Arthens’ grandiose style and the descriptions of over-the-top meals but, unlike the somewhat similar The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester, this doesn’t have much of a payoff.

Pierre Arthens, France’s most formidable food critic, is on his deathbed reliving his most memorable meals and searching for one elusive flavor to experience again before he dies. He’s proud of his accomplishments – “I have covered the entire range of culinary art, for I am an encyclopedic esthete who is always one dish ahead of the game” – and expresses no remorse for his affairs and his coldness as a father. This takes place in the same apartment building as The Elegance of the Hedgehog and is in short first-person chapters narrated by various figures from Arthens’ life. His wife, his children and his doctor are expected, but we also hear from the building’s concierge, a homeless man he passed every day for ten years, and even a sculpture in his study. I liked Arthens’ grandiose style and the descriptions of over-the-top meals but, unlike the somewhat similar The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester, this doesn’t have much of a payoff.  The main action is set between 1861 and 1874, as married French merchant Hervé Joncour makes four journeys to and from Japan to acquire silkworms. “This place, Japan, where precisely is it?” he asks before his first trip. “Just keep going. Right to the end of the world,” Baldabiou, the silk mill owner, replies. On his first journey, Joncour is instantly captivated by his Japanese advisor’s concubine, though they haven’t exchanged a single word, and from that moment on nothing in his life can make up for the lack of her. At first I found the book slightly repetitive and fable-like, but as it went on I grew more impressed with the seeds Baricco has planted that lead to a couple of major surprises. At the end I went back and reread a number of chapters to pick up on the clues. I’d had this book recommended from a variety of quarters, first by Karen Shepard when I interviewed her for Bookkaholic in 2013, so I’m glad I finally found a copy in a charity shop.

The main action is set between 1861 and 1874, as married French merchant Hervé Joncour makes four journeys to and from Japan to acquire silkworms. “This place, Japan, where precisely is it?” he asks before his first trip. “Just keep going. Right to the end of the world,” Baldabiou, the silk mill owner, replies. On his first journey, Joncour is instantly captivated by his Japanese advisor’s concubine, though they haven’t exchanged a single word, and from that moment on nothing in his life can make up for the lack of her. At first I found the book slightly repetitive and fable-like, but as it went on I grew more impressed with the seeds Baricco has planted that lead to a couple of major surprises. At the end I went back and reread a number of chapters to pick up on the clues. I’d had this book recommended from a variety of quarters, first by Karen Shepard when I interviewed her for Bookkaholic in 2013, so I’m glad I finally found a copy in a charity shop.

Hardwick’s 1979 work is composed of (autobiographical?) fragments about the people and places that make up a woman’s remembered past. Elizabeth shares a New York City apartment with a gay man; lovers come and go; she mourns for Billie Holiday; there are brief interludes in Amsterdam and other foreign destinations. She sends letters to “Dearest M.” and back home to Kentucky, where her mother raised nine children. (“My mother’s femaleness was absolute, ancient, and there was a peculiar, helpless assertiveness about it. … This fateful fertility kept her for most of her life under the dominion of nature.”) There’s some astonishingly good writing here, but as was the case for me with Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t quite see how it was all meant to fit together.

Hardwick’s 1979 work is composed of (autobiographical?) fragments about the people and places that make up a woman’s remembered past. Elizabeth shares a New York City apartment with a gay man; lovers come and go; she mourns for Billie Holiday; there are brief interludes in Amsterdam and other foreign destinations. She sends letters to “Dearest M.” and back home to Kentucky, where her mother raised nine children. (“My mother’s femaleness was absolute, ancient, and there was a peculiar, helpless assertiveness about it. … This fateful fertility kept her for most of her life under the dominion of nature.”) There’s some astonishingly good writing here, but as was the case for me with Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t quite see how it was all meant to fit together.  West was a contemporary of F. Scott Fitzgerald; in fact, the story goes that when he died in a car accident at age 37, he had been rushing to Fitzgerald’s wake, and the friends were given adjoining rooms in a Los Angeles funeral home. Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” (never given any other name) is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden, the unloved. Not surprisingly, the secondhand woes start to get him down (“his heart remained a congealed lump of icy fat”), and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. Indeed, I was startled by how explicit the language and sexual situations are; this doesn’t feel like a book from 1933. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference really struck me, and the last few chapters, in which a drastic change of life is proffered but then cruelly denied, are masterfully plotted. The 2014 Daunt Books reissue has been given a cartoon cover and a puff from Jonathan Lethem to emphasize how contemporary it feels.

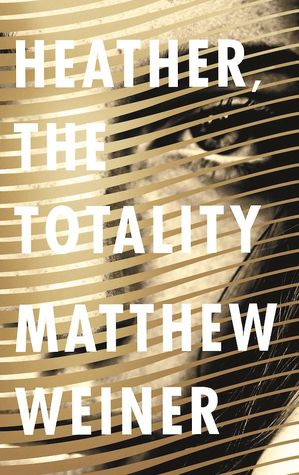

West was a contemporary of F. Scott Fitzgerald; in fact, the story goes that when he died in a car accident at age 37, he had been rushing to Fitzgerald’s wake, and the friends were given adjoining rooms in a Los Angeles funeral home. Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” (never given any other name) is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden, the unloved. Not surprisingly, the secondhand woes start to get him down (“his heart remained a congealed lump of icy fat”), and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. Indeed, I was startled by how explicit the language and sexual situations are; this doesn’t feel like a book from 1933. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference really struck me, and the last few chapters, in which a drastic change of life is proffered but then cruelly denied, are masterfully plotted. The 2014 Daunt Books reissue has been given a cartoon cover and a puff from Jonathan Lethem to emphasize how contemporary it feels.  This was very nearly a one-sitting read for me: Clare gave me a copy at our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel decision meeting and I read all but a few pages on the train home from London. Famously, Matthew Weiner is the creator of Mad Men, but instead of 1960s stylishness this debut novella is full of all-too-believable creepiness and a crescendo of dubious decisions. Mark and Karen Breakstone have one beloved daughter, Heather. We follow them for years, getting little snapshots of a normal middle-class family. One summer, as their New York City apartment building is being renovated, the teenaged Heather catches the eye of a construction worker who has a criminal past – as we’ve learned through a parallel narrative about his life. I had no idea what I would conclude about this book until the last few pages; it was all going to be a matter of how Weiner brought things together. And he does so really satisfyingly, I think. It’s a subtle, Hitchcockian story, and that title is so sly: We never get the totality of anyone; we only see shards here and there – something the cover portrays very well – and make judgments we later have to rethink.

This was very nearly a one-sitting read for me: Clare gave me a copy at our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel decision meeting and I read all but a few pages on the train home from London. Famously, Matthew Weiner is the creator of Mad Men, but instead of 1960s stylishness this debut novella is full of all-too-believable creepiness and a crescendo of dubious decisions. Mark and Karen Breakstone have one beloved daughter, Heather. We follow them for years, getting little snapshots of a normal middle-class family. One summer, as their New York City apartment building is being renovated, the teenaged Heather catches the eye of a construction worker who has a criminal past – as we’ve learned through a parallel narrative about his life. I had no idea what I would conclude about this book until the last few pages; it was all going to be a matter of how Weiner brought things together. And he does so really satisfyingly, I think. It’s a subtle, Hitchcockian story, and that title is so sly: We never get the totality of anyone; we only see shards here and there – something the cover portrays very well – and make judgments we later have to rethink.  Pachinko by Min Jin Lee (for BookBrowse) [Feb. 7, Grand Central]: “Pachinko follows one Korean family through the generations, beginning in [the] early 1900s. … [A] sweeping saga of an exceptional family in exile from its homeland and caught in the indifferent arc of history.”

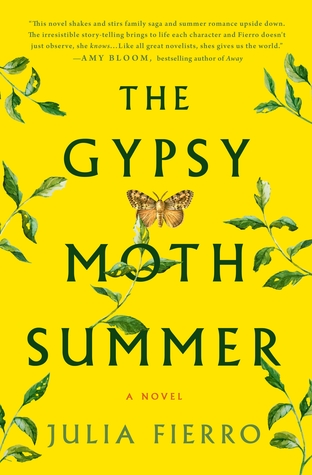

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee (for BookBrowse) [Feb. 7, Grand Central]: “Pachinko follows one Korean family through the generations, beginning in [the] early 1900s. … [A] sweeping saga of an exceptional family in exile from its homeland and caught in the indifferent arc of history.” Gypsy Moth Summer by Julia Fierro [June 6, St. Martin’s]: “It is the summer of 1992 and a gypsy moth invasion blankets Avalon Island. … The Gypsy Moth Summer is about love, gaps in understanding, and the struggle to connect: within families; among friends; between neighbors and entire generations.” – Plus, get a load of that gorgeous cover!

Gypsy Moth Summer by Julia Fierro [June 6, St. Martin’s]: “It is the summer of 1992 and a gypsy moth invasion blankets Avalon Island. … The Gypsy Moth Summer is about love, gaps in understanding, and the struggle to connect: within families; among friends; between neighbors and entire generations.” – Plus, get a load of that gorgeous cover! The Awkward Age by Francesca Segal [May 4, Chatto & Windus]: “In a Victorian terraced house, in north-west London, two families have united in imperfect harmony. … This is a moving and powerful novel about the modern family: about starting over; about love, guilt, and generosity; about building something beautiful amid the mess and complexity of what came before.” – Sounds like Ann Patchett’s Commonwealth…

The Awkward Age by Francesca Segal [May 4, Chatto & Windus]: “In a Victorian terraced house, in north-west London, two families have united in imperfect harmony. … This is a moving and powerful novel about the modern family: about starting over; about love, guilt, and generosity; about building something beautiful amid the mess and complexity of what came before.” – Sounds like Ann Patchett’s Commonwealth… A Separation by Katie Kitamura [Feb. 7, Riverhead Books]: “A mesmerizing, psychologically taut novel about a marriage’s end and the secrets we all carry.”

A Separation by Katie Kitamura [Feb. 7, Riverhead Books]: “A mesmerizing, psychologically taut novel about a marriage’s end and the secrets we all carry.” Poetry Can Save Your Life: A Memoir by Jill Bialosky [June 13, Atria]: “[A]n unconventional coming-of-age memoir organized around the 43 remarkable poems that gave her insight, courage, compassion, and a sense of connection at pivotal moments in her life.”

Poetry Can Save Your Life: A Memoir by Jill Bialosky [June 13, Atria]: “[A]n unconventional coming-of-age memoir organized around the 43 remarkable poems that gave her insight, courage, compassion, and a sense of connection at pivotal moments in her life.” Theft by Finding: Diaries (1977–2002) by David Sedaris [May 30, Little, Brown & Co.]: “[F]or the first time in print: selections from the diaries that are the source of his remarkable autobiographical essays.”

Theft by Finding: Diaries (1977–2002) by David Sedaris [May 30, Little, Brown & Co.]: “[F]or the first time in print: selections from the diaries that are the source of his remarkable autobiographical essays.” More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers by Jonathan Lethem [Mar. 14, Melville House]: “[C]ollects more than a decade of Lethem’s finest writing on writing, with new and previously unpublished material, including: impassioned appeals for forgotten writers and overlooked books, razor-sharp essays, and personal accounts of his most extraordinary literary encounters and discoveries.”

More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers by Jonathan Lethem [Mar. 14, Melville House]: “[C]ollects more than a decade of Lethem’s finest writing on writing, with new and previously unpublished material, including: impassioned appeals for forgotten writers and overlooked books, razor-sharp essays, and personal accounts of his most extraordinary literary encounters and discoveries.”