(Goodbye to) Winter Reads by Sylvia Plath (#ReadIndies) & Kathleen Winter

The sunshine, temperatures and flora suggest that spring is here to stay, though I wouldn’t be surprised by a return of the cold and wet in March. We live in the wrong part of the UK for snow lovers; we didn’t get any snow this winter, apart from some early-morning flurries one day when I was fast asleep. My seasonal reading consisted of a lesser-known posthumous poetry collection, a record of a sea voyage past Greenland, and a silly children’s book.

Winter Trees by Sylvia Plath (1971)

A prefatory note from Ted Hughes explains that these poems “are all out of the batch from which the Ariel poems were more or less arbitrarily chosen and they were all composed in the last nine months of Sylvia Plath’s life.” Ariel is much the stronger collection. There are only 19 poems here; the final one, “Three Women,” is more of a play (subtitled “A Poem for Three Voices”) set on a maternity ward. Motherhood is a central concern throughout. There’s harsh, unpleasant language around womanhood in general. The opening title poem is a marvel of artistic imagery, assonance and internal rhyme, but also contains a metaphor that made me cringe: “Knowing neither abortions nor bitchery, / Truer than women, / They seed so effortlessly!”

A prefatory note from Ted Hughes explains that these poems “are all out of the batch from which the Ariel poems were more or less arbitrarily chosen and they were all composed in the last nine months of Sylvia Plath’s life.” Ariel is much the stronger collection. There are only 19 poems here; the final one, “Three Women,” is more of a play (subtitled “A Poem for Three Voices”) set on a maternity ward. Motherhood is a central concern throughout. There’s harsh, unpleasant language around womanhood in general. The opening title poem is a marvel of artistic imagery, assonance and internal rhyme, but also contains a metaphor that made me cringe: “Knowing neither abortions nor bitchery, / Truer than women, / They seed so effortlessly!”

That paints motherhood as hard won, as “Childless Woman” reinforces by turning purposeless menstruation into a horror story with its vocabulary of “a child’s shriek” — “Spiderlike” — “Uttering nothing but blood— / Taste it, dark red!” — “My funeral” — “the mouths of corpses”. Plath was certainly ambivalent about babies (“Thalidomide” is particularly frightening) but I bristled at childlessness being linked with living only for oneself. Then again, pretty much everything – men, God, travel, animals – is portrayed negatively here. “Winter Trees” is the single poem I’d anthologize. (University library) ![]()

Published by Faber, so counts for #ReadIndies

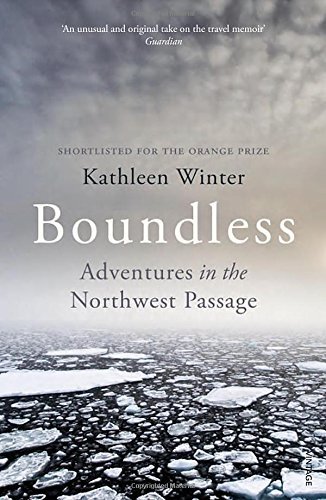

Boundless: Adventures in the Northwest Passage by Kathleen Winter (2015)

I read this excellent travel book slowly, over most of the winter, including during that surreal period when He Who Shall Not Be Named was threatening to annex Greenland. Winter was invited to be a writer-in-residence aboard an icebreaker travelling through the Northwest Passage, past southwest Greenland and threading between the islands of the Canadian Arctic. She was prepared: a friend had taught her that the only thing to say in these sorts of lucky, unexpected scenarios is “My bags are already packed.” Her ‘getaway bag’ of two pairs of underwear, a T-shirt, a pair of jeans, and a LBD wasn’t exactly Arctic-ready, but she still had a head start. She adds an old concertina and worn hiking boots that resemble “lobes of some mushroom cracked off the bole of an old warrior tree.”

I read this excellent travel book slowly, over most of the winter, including during that surreal period when He Who Shall Not Be Named was threatening to annex Greenland. Winter was invited to be a writer-in-residence aboard an icebreaker travelling through the Northwest Passage, past southwest Greenland and threading between the islands of the Canadian Arctic. She was prepared: a friend had taught her that the only thing to say in these sorts of lucky, unexpected scenarios is “My bags are already packed.” Her ‘getaway bag’ of two pairs of underwear, a T-shirt, a pair of jeans, and a LBD wasn’t exactly Arctic-ready, but she still had a head start. She adds an old concertina and worn hiking boots that resemble “lobes of some mushroom cracked off the bole of an old warrior tree.”

It’s not a long or gruelling trip, so there’s not much of the bellyaching that bores me in trekking books. Winter is interested in everything: birds, folk music, Indigenous arts and crafts, her fellow passengers’ stories, the infamous lost Arctic expeditions, and her family’s history in England and Canada. She collects her scraps of notes in a Ziploc, and that’s what this book is – a grab bag. Winter is enthusiastic yet prioritizes quiet epiphanies about the sacredness of land and creatures over thrills – though their vessel does get stranded on rocks and requires a Coast Guard rescue. It would be interesting to reread her Orange Prize-shortlisted novel about an intersex person, Annabel. (If you hanker to go deeper about Greenland, read This Cold Heaven by Gretel Ehrlich and Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow by Peter Høeg.) (Secondhand – Bas Books) ![]()

& A bonus children’s book:

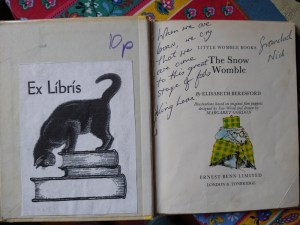

The Snow Womble by Elisabeth Beresford; illus. Margaret Gordon (1975) – I thought this would be a cute one to read even though I’m unfamiliar with the Wombles. But it’s just a one-note extended joke about the creatures not being able to tell their snowman version of Great-Uncle Bulgaria apart from the real one. The best thing about reading this was the frontispiece’s juxtaposition of elements: the computer-printed bookplate, the nominal secondhand price (withdrawn from London Borough of Sutton Public Libraries), and the wholly inappropriate inscription Grandad Nick chose from King Lear! (Little Free Library)

The Snow Womble by Elisabeth Beresford; illus. Margaret Gordon (1975) – I thought this would be a cute one to read even though I’m unfamiliar with the Wombles. But it’s just a one-note extended joke about the creatures not being able to tell their snowman version of Great-Uncle Bulgaria apart from the real one. The best thing about reading this was the frontispiece’s juxtaposition of elements: the computer-printed bookplate, the nominal secondhand price (withdrawn from London Borough of Sutton Public Libraries), and the wholly inappropriate inscription Grandad Nick chose from King Lear! (Little Free Library)

Carol Shields Prize Reading: Daughter and Dances

Two more Carol Shields Prize nominees today: from the shortlist, the autofiction-esque story of a father and daughter, both writers, and their dysfunctional family; and, from the longlist, a debut novel about the physical and emotional rigours of being a Black ballet dancer.

Daughter by Claudia Dey

Like her protagonist, Mona Dean, Dey is a playwright, but the Canadian author has clearly stated that her third novel is not autofiction, even though it may feel like it. (Fragmentary sections, fluidity between past and present, a lack of speech marks; not to mention that Dey quotes Rachel Cusk and there’s even a character named Sigrid.) Mona’s father, Paul, is a serial adulterer who became famous for his novel Daughter and hasn’t matched that success in the 20 years since. He left Mona and Juliet’s mother, Natasha, for Cherry, with whom he had another daughter, Eva. There have been two more affairs. Every time Mona meets Paul for a meal or a coffee, she’s returned to a childhood sense of helplessness and conflict.

I had a sordid contract with my father. I was obsessed with my childhood. I had never gotten over my childhood. Cherry had been cruel to me as a child, and I wanted to get back at Cherry, and so I guarded my father’s secrets like a stash of weapons, waiting for the moment I could strike.

It took time for me to warm to Dey’s style, which is full of flat, declarative sentences, often overloaded with character names. The phrasing can be simple and repetitive, with overuse of comma splices. At times Mona’s unemotional affect seems to be at odds with the melodrama of what she’s recounting: an abortion, a rape, a stillbirth, etc. I twigged to what Dey was going for here when I realized the two major influences were Hemingway and Shakespeare.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

Mona’s breakthrough play is Margot, based on the life of one Hemingway granddaughter, and she’s working on a sequel about another. There are four women in Paul’s life, and Mona once says of him during a period of writer’s block, “He could not write one true sentence.” So Paul (along with Mona, along with Dey) may be emulating Hemingway.

And then there’s the King Lear setup. (I caught on to this late, perhaps because I was also reading a more overt Lear update at the time, Private Rites by Julia Armfield.) The larger-than-life father; the two older daughters and younger half-sister; the resentment and estrangement. Dey makes the parallel explicit when Mona, musing on her Hemingway-inspired oeuvre, asks, “Why had Shakespeare not called the play King Lear’s Daughters?”

Were it not for this intertextuality, it would be a much less interesting book. And, to be honest, the style was not my favourite. There were some lines that really irked me (“The flowers they were considering were flamboyant to her eye, she wanted less flamboyant flowers”; “Antoine barked. He was barking.”; “Outside, it sunned. Outside, it hailed.”). However, rather like Sally Rooney, Dey has prioritized straightforward readability. I found that I read this quickly, almost as if in a trance, inexorably drawn into this family’s drama. ![]()

Related reads: Monsters by Claire Dederer, The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright, The Wife by Meg Wolitzer, Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Farrar, Straus and Giroux for the free e-copy for review.

Also from the shortlist:

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan – The only novel that is on both the CSP and Women’s Prize shortlists. I dutifully borrowed a copy from the library, but the combination of the heavy subject matter (Sri Lanka’s civil war and the Tamil Tigers resistance movement) and the very small type in the UK hardback quickly defeated me, even though I was enjoying Sashi’s quietly resolute voice and her medical training to work in a field hospital. I gave it a brief skim. The author researched this second novel for 20 years, and her narrator is determined to make readers grasp what went on: “You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived … You must understand: There is no single day on which a war begins.” I know from Laura and Marcie that this is top-class historical fiction, never mawkish or worthy, so I may well try it some other time when I have the fortitude.

Longlisted:

Dances by Nicole Cuffy

This was a buddy read with Laura (see her review); I think we both would have liked to see it on the shortlist as, though we’re not dancers ourselves, we’re attracted to the artistry and physicality of ballet. It’s always a privilege to get an inside glimpse of a rarefied world, and to see people at work, especially in a field that requires single-mindedness and self-discipline. Cuffy’s debut novel focuses on 22-year-old Celine Cordell, who becomes the first Black female principal in the New York City Ballet. Cece marvels at the distance between her Brooklyn upbringing – a single mother and drug-dealing older brother, Paul – and her new identity as a celebrity who has brand endorsements and gets stopped on the street for selfies.

Even though Kaz, the director, insists that “Dance has no race,” Cece knows it’s not true. (And Kaz in some ways exaggerates her difference, creating a role for her in a ballet based around Gullah folklore from South Carolina.) Cece has always had to work harder than the others in the company to be accepted:

Ballet has always been about the body. The white body, specifically. So they watched my Black body, waited for it to confirm their prejudices, grew ever more anxious as it failed to do so, again and again.

A further complication is her relationship with Jasper, her white dance partner. It’s an open secret in the company that they’re together, but to the press they remain coy. Cece’s friends Irine and Ryn support her through rocky times, and her former teachers, Luca and Galina, are steadfast in their encouragement. Late on, Cece’s search for Paul, who has been missing for five years, becomes a surprisingly major element. While the sibling bond helps the novel stand out, I most enjoyed the descriptions of dancing. All of the sections and chapters are titled after ballet terms, and even when I was unfamiliar with the vocabulary or the music being referenced, I could at least vaguely picture all the moves in my head. It takes real skill to render other art forms in words. I’ll look forward to following Cuffy’s career. ![]()

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and One World for the free e-copy for review.

Currently reading:

(Shortlist) Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote

(Longlist) Between Two Moons by Aisha Abdel Gawad

Up next:

(Longlist) You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy

I’m aiming for one more batch of reviews (and a prediction) before the winner is announced on 13 May.

Last-Minute Thoughts on the Booker Longlist

Tomorrow, the 20th, the Man Booker Prize shortlist will be announced. This must be my worst showing for many years: I’ve read just two of the longlisted books, and both were such disappointments I had to wonder why they’d been nominated at all. I have six of the others on request from the public library; of them I’m most keen to read The Overstory and Sabrina, the first graphic novel to have been recognized (the others are by Gunaratne, Johnson, Kushner and Ryan, but I’ll likely cancel my holds if they don’t make the shortlist). I’d read Robin Robertson’s novel-in-verse if I ever managed to get hold of a copy, but I’ve decided I’m not interested in the other four nominees (Bauer, Burns, Edugyan, Ondaatje*).

The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh

(Excerpted from my upcoming review for New Books magazine’s Booker Prize roundup.)

The first word of The Water Cure may be “Once,” but what follows is no fairy tale. Here’s the rest of that sentence: “Once we have a father, but our father dies without us noticing.” The tense seems all wrong; surely it should be “had” and “died”? From the very first line, then, Sophie Mackintosh’s debut novel has the reader wrong-footed, and there are many more moments of confusion to come. The other thing to notice in the opening sentence is the use of the first person plural. That “we” refers to three sisters: Grace, Lia and Sky. After the death of their father, King, it’s just them and their mother in a grand house on a remote island.

The first word of The Water Cure may be “Once,” but what follows is no fairy tale. Here’s the rest of that sentence: “Once we have a father, but our father dies without us noticing.” The tense seems all wrong; surely it should be “had” and “died”? From the very first line, then, Sophie Mackintosh’s debut novel has the reader wrong-footed, and there are many more moments of confusion to come. The other thing to notice in the opening sentence is the use of the first person plural. That “we” refers to three sisters: Grace, Lia and Sky. After the death of their father, King, it’s just them and their mother in a grand house on a remote island.

There are frequent flashbacks to times when damaged women used to come here for therapy that sounds more like torture. The sisters still engage in similar sadomasochistic practices: sitting in a hot sauna until they faint, putting their hands and feet in buckets of ice, and playing the “drowning game” in the pool by putting on a dress laced with lead weights. Despite their isolation, the sisters are still affected by the world at large. At the end of Part I, three shipwrecked men wash up on shore and request sanctuary. The men represent new temptations and a threat to the sisters’ comfort zone.

This is a strange and disorienting book. The atmosphere – lonely and lowering – is the best thing about it. Its setup is somewhat reminiscent of two Shakespeare plays, King Lear and The Tempest. With the exception of a few lines like “we look towards the rounded glow of the horizon, the air peach-ripe with toxicity,” the prose draws attention to itself in a bad way: it’s consciously literary and overwritten. In terms of the plot, it is difficult to understand, at the most basic level, what is going on and why. Speculative novels with themes of women’s repression are a dime a dozen nowadays, and the interested reader will find a better example than this one.

My rating:

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Conversations with Friends was one of last year’s sleeper hits and a surprise favorite of mine. You may remember that I was part of an official shadow panel for the 2017 Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, which I was pleased to see Sally Rooney win. So I jumped at the chance to read her follow-up novel, which has been earning high praise from critics and ordinary readers alike as being even better than her debut. Alas, though, I was let down.

Normal People is very similar to Tender – which for some will be high praise indeed, though I never managed to finish Belinda McKeon’s novel – in that both realistically address the intimacy between a young woman and a young man during their university days and draw class and town-and-country distinctions (the latter of which might not mean much to those who are unfamiliar with Ireland).

Normal People is very similar to Tender – which for some will be high praise indeed, though I never managed to finish Belinda McKeon’s novel – in that both realistically address the intimacy between a young woman and a young man during their university days and draw class and town-and-country distinctions (the latter of which might not mean much to those who are unfamiliar with Ireland).

The central characters here are two loners: Marianne Sheridan, who lives in a white mansion with her distant mother and sadistic older brother Alan, and Connell Waldron, whose single mother cleans Marianne’s house. Connell doesn’t know who his father is; Marianne’s father died when she was 13, but good riddance – he hit her and her mother. Marianne and Connell start hooking up during high school in Carricklea, but Connell keeps their relationship a secret because Marianne is perceived as strange and unpopular. At Trinity College Dublin they struggle to fit in and keep falling into bed with each other even though they’re technically seeing other people.

The novel, which takes place between 2011 and 2015, keeps going back and forth in time by weeks or months, jumping forward and then filling in the intervening time with flashbacks. I kept waiting for more to happen, skimming ahead to see if there would be anything more to it than drunken college parties and frank sex scenes. The answer is: not really; that’s mostly what the book is composed of.

I can see what Rooney is trying to do here (she makes it plain in the next-to-last paragraph): to show how one temporary, almost accidental relationship can change the partners for the better, giving Connell the impetus to pursue writing and Marianne the confidence to believe she is loveable, just like ‘normal people’. It is appealing to see into these characters’ heads and compare what they think of themselves and each other with their awareness of what others think. But page to page it is pretty tedious, and fairly unsubtle.

I was interested to learn that Rooney was writing this at the same time as Conversations, and initially intended it to be short stories. It’s possible I would have appreciated it more in that form.

My rating:

My thanks to Faber & Faber for the free copy for review.

*I’ve only ever read the memoir Running in the Family plus a poetry collection by Ondaatje. I have a copy of The English Patient on the shelf and have felt guilty for years about not reading it, especially after it won the “Golden Booker” this past summer (see Annabel’s report on the ceremony). I had grand plans of reading all the Booker winners on my shelf – also including Carey and Keneally – in advance of the 50th anniversary celebrations, but didn’t even make it through the books I started by the two South African winners; my aborted mini-reviews are part of the Shiny New Books coverage here. (There are also excerpts from my reviews of Bring Up the Bodies, The Sellout and Lincoln in the Bardo here.)

*I’ve only ever read the memoir Running in the Family plus a poetry collection by Ondaatje. I have a copy of The English Patient on the shelf and have felt guilty for years about not reading it, especially after it won the “Golden Booker” this past summer (see Annabel’s report on the ceremony). I had grand plans of reading all the Booker winners on my shelf – also including Carey and Keneally – in advance of the 50th anniversary celebrations, but didn’t even make it through the books I started by the two South African winners; my aborted mini-reviews are part of the Shiny New Books coverage here. (There are also excerpts from my reviews of Bring Up the Bodies, The Sellout and Lincoln in the Bardo here.)

Last year I’d read enough from the Booker longlist to make predictions and a wish list, but this year I have no clue. I’ll just have a look at the shortlist tomorrow and see if any of the remaining contenders appeal.

What have you managed to read from the Booker longlist? Do you have any predictions for the shortlist?

Now in November by Josephine Johnson

I’d never heard of this 1935 Pulitzer Prize winner before I saw a large display of titles from publisher Head of Zeus’s new imprint, Apollo, at Foyles bookshop in London the night of the Diana Athill event. Apollo, which launched with eight titles in April, aims to bring lesser-known classics out of obscurity: by making “great forgotten works of fiction available to a new generation of readers,” it intends to “challenge the established canon and surprise readers.” I’ll be reviewing Howard Spring’s My Son, My Son for Shiny New Books soon, and I’m tempted by the Eudora Welty and Christina Stead titles. Rounding out the list are two novels set in Eastern Europe, a Sardinian novel in translation, and an underrated Western.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

The arrival of Grant Koven, a neighbor in his thirties hired to help Arnold with hard labor, seems like the only thing that might break the agricultural cycle of futile hope and disappointment. Marget quickly falls in love with him, but it takes her a while to realize that her sisters are smitten too. They all keep hoping their fortunes will change:

‘This year will have to be different,’ I thought. ‘We’ve scrabbled and prayed too long for it to end as the others have.’ The debt was still like a bottomless swamp unfilled, where we had gone year after year, throwing in hours of heat and the wrenching on stony land, only to see them swallowed up and then to creep back and begin again.

Yet as drought settles in, things only get worse. The fear of losing everything becomes a collective obsession; a sense of insecurity pervades the community. The Ramseys, black tenant farmers with nine children, are evicted. Milk producers go on strike and have to give the stuff away before it sours. Nature is indifferent and neither is there a benevolent God at work: when the Haldmarnes go to church, they are refused communion as non-members.

Marget skips around in time to pinpoint the central moments of their struggle, her often fragmentary thoughts joined by ellipses – a style that seemed to me ahead of its time:

if anything could fortify me against whatever was to come […] it would have to be the small and eternal things – the whip-poor-wills’ long liquid howling near the cave… the shape of young mules against the ridge, moving lighter than bucks across the pasture… things like the chorus of cicadas, and the ponds stained red in evenings.

Michael Schmidt, the critic who selected the first eight Apollo books, likens Now in November to the work of two very different female writers: Marilynne Robinson and Emily Brontë. What I think he is emphasizing with those comparisons is the sense of isolation and the feeling that struggle is writ large on the landscape. The Haldmarne sisters certainly wander the nearby hills like the Brontë sisters did the Yorkshire moors.

The cover image, reproduced in full on the endpapers, is Jackson Pollock’s “Man with Hand Plow,” c. 1933.

As points of reference I would also add Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres and Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia (resurrected by NYRB Classics in 2014), which also give timeless weight to the female experience of Midwest farming. Like the Smiley, Now in November stars a trio of sisters and makes conscious allusions to King Lear. Kerrin reads the play and thinks of their father as Lear, while Marget quotes it as a prophecy that the worst is yet to come: “I remembered the awful words in Lear: ‘The worst is not so long as we can say “This is the worst.”’ Already this year, I’d cried, This is enough! uncounted times, and the end had never come.”

Johnson lived to age 80 and published another 11 books, but nothing ever lived up to the success of her first. This is an atmospheric and strangely haunting novel. The plot is simple enough, but the writing elevates it into something special. The plaintive tone, the folksy metaphors, and the philosophical earnestness all kept me eagerly traveling along with Marget to see where this tragic story might lead. Apollo has done the literary world a great favor in bringing this lost classic to light.

With thanks to Blake Brooks at Head of Zeus for the free copy.

My rating:

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

My third by Adichie this year, and an ideal follow-up to

My third by Adichie this year, and an ideal follow-up to

“Why do people travel? … I suppose to lose part of themselves. Parts which trap us. Or maybe because it is possible, and it helps us believe there is a future.”

“Why do people travel? … I suppose to lose part of themselves. Parts which trap us. Or maybe because it is possible, and it helps us believe there is a future.”

Who could resist such a title and cover?! Unfortunately, I didn’t warm to Eisenberg’s writing and got little out of these stories, especially “Merge,” the longest and only one of the six that hadn’t previously appeared in print. The title implies collective responsibility and is applied to a story of artists on a retreat in Europe. “The Third Tower” has a mental hospital setting. In “Recalculating,” a character only learns about an estranged uncle after his death. The two I liked most were “Taj Mahal,” about competing views of a filmmaker from the golden days of Hollywood, and “Cross Off and Move On,” about a family’s Holocaust history. But all are very murky in my head. (See Susan’s more positive

Who could resist such a title and cover?! Unfortunately, I didn’t warm to Eisenberg’s writing and got little out of these stories, especially “Merge,” the longest and only one of the six that hadn’t previously appeared in print. The title implies collective responsibility and is applied to a story of artists on a retreat in Europe. “The Third Tower” has a mental hospital setting. In “Recalculating,” a character only learns about an estranged uncle after his death. The two I liked most were “Taj Mahal,” about competing views of a filmmaker from the golden days of Hollywood, and “Cross Off and Move On,” about a family’s Holocaust history. But all are very murky in my head. (See Susan’s more positive  Last year I loved reading Mantel’s collection

Last year I loved reading Mantel’s collection  There’s a nastiness to these early McEwan stories that reminded me of Never Mind by Edward St. Aubyn. The teenage narrator of “Homemade” tells you right in the first paragraph that his will be a tale of incest. A little girl’s body is found in the canal in “Butterflies.” The voice in “Conversation with a Cupboard Man” is that of someone who has retreated into solitude after being treated cruelly at the workplace (“I hate going outside. I prefer it in my cupboard”). “Last Day of Summer” seems like a lovely story about a lodger being accepted as a member of the family … until the horrific last page. Only “Cocker at the Theatre” was pure comedy, of the raunchy variety (emphasis on “cock”). You get the sense of a talented writer whose mind you really wouldn’t want to spend time in; had this been my first exposure to McEwan, I would probably never have opened up another of his books. [Public library]

There’s a nastiness to these early McEwan stories that reminded me of Never Mind by Edward St. Aubyn. The teenage narrator of “Homemade” tells you right in the first paragraph that his will be a tale of incest. A little girl’s body is found in the canal in “Butterflies.” The voice in “Conversation with a Cupboard Man” is that of someone who has retreated into solitude after being treated cruelly at the workplace (“I hate going outside. I prefer it in my cupboard”). “Last Day of Summer” seems like a lovely story about a lodger being accepted as a member of the family … until the horrific last page. Only “Cocker at the Theatre” was pure comedy, of the raunchy variety (emphasis on “cock”). You get the sense of a talented writer whose mind you really wouldn’t want to spend time in; had this been my first exposure to McEwan, I would probably never have opened up another of his books. [Public library]

Retired professor Nariman Vakeel, 79, has Parkinson’s disease and within the first few chapters has also fallen and broken his ankle. His grown stepchildren, Coomy and Jal, reluctant to care for him anyway, decide they can’t cope with the daily reality of bedpans, sponge baths and spoon feeding in their large Chateau Felicity apartment. He’ll simply have to recuperate at Pleasant Villa with his daughter Roxana and her husband and sons, even though their two-bedroom apartment is barely large enough for the family of four. You have to wince at the irony of the names for these two Bombay housing blocks, and at the bitter contrast between selfishness and duty.

Retired professor Nariman Vakeel, 79, has Parkinson’s disease and within the first few chapters has also fallen and broken his ankle. His grown stepchildren, Coomy and Jal, reluctant to care for him anyway, decide they can’t cope with the daily reality of bedpans, sponge baths and spoon feeding in their large Chateau Felicity apartment. He’ll simply have to recuperate at Pleasant Villa with his daughter Roxana and her husband and sons, even though their two-bedroom apartment is barely large enough for the family of four. You have to wince at the irony of the names for these two Bombay housing blocks, and at the bitter contrast between selfishness and duty. Like a cross between Angela’s Ashes and Toast, this recreates a fairly horrific upbringing from the child’s perspective. Barr was an intelligent, creative young man who early on knew that he was gay and, not just for that reason, often felt that there was no place for him: neither in working-class Scotland, where his father was a steelworker and his brain-damaged mother flitted from one violent boyfriend to another; nor in Maggie Thatcher’s 1980s Britain at large, in which money was the reward for achievement and the individual was responsible for his own moral standing and worldly advancement. “I don’t need to stand out any more,” he recalls, being “six foot tall, scarecrow skinny and speccy with join-the-dots spots, bottle-opener buck teeth and a thing for waistcoats. Plus I get free school dinners and I’m gay.”

Like a cross between Angela’s Ashes and Toast, this recreates a fairly horrific upbringing from the child’s perspective. Barr was an intelligent, creative young man who early on knew that he was gay and, not just for that reason, often felt that there was no place for him: neither in working-class Scotland, where his father was a steelworker and his brain-damaged mother flitted from one violent boyfriend to another; nor in Maggie Thatcher’s 1980s Britain at large, in which money was the reward for achievement and the individual was responsible for his own moral standing and worldly advancement. “I don’t need to stand out any more,” he recalls, being “six foot tall, scarecrow skinny and speccy with join-the-dots spots, bottle-opener buck teeth and a thing for waistcoats. Plus I get free school dinners and I’m gay.”

I enjoyed this immensely, from the first line on: “The day I returned to Templeton steeped in disgrace, the fifty-foot corpse of a monster surfaced in Lake Glimmerglass.” Twenty-eight-year-old Willie Upton is back in her hometown, pregnant by her older, married archaeology professor after a summer of PhD fieldwork in Alaska. “I had come home to be a child again. I was sick, heartbroken, worn down.” She gives herself a few weeks back home to dig through her family history to find her father – whom Vi has never identified – and decide whether she’s ready to be a mother herself.

I enjoyed this immensely, from the first line on: “The day I returned to Templeton steeped in disgrace, the fifty-foot corpse of a monster surfaced in Lake Glimmerglass.” Twenty-eight-year-old Willie Upton is back in her hometown, pregnant by her older, married archaeology professor after a summer of PhD fieldwork in Alaska. “I had come home to be a child again. I was sick, heartbroken, worn down.” She gives herself a few weeks back home to dig through her family history to find her father – whom Vi has never identified – and decide whether she’s ready to be a mother herself. Still to read: Jitterbug Perfume by Tom Robbins (CURE: horror of ageing)

Still to read: Jitterbug Perfume by Tom Robbins (CURE: horror of ageing)