#NovNov23 and #SciFiMonth: They by Kay Dick

To join the Week 3 theme of Novellas in November, “Broadening My Horizons,” with Science Fiction Month (celebrating a genre I still struggle with but occasionally enjoy), I decided to pick up a short rediscovered dystopian classic. Originally published in 1977, They: A Sequence of Unease was reissued by Faber Editions last year. I had never heard of its author, Kay Dick (1915–2001), a lesbian bookseller and publisher who lived in London and Brighton and wrote seven works of fiction and three biographies.

Although I can think of a few dystopian novels that I have loved, it’s not a mode I gravitate towards. This makes me out of step with the zeitgeist, I know, because dystopian stories are only rising in popularity as current events converge with premonitory visions of the future.

The specific problem I had with They is one I’ve had with some other speculative works: vagueness. I can’t stand it when allegorical books are set in a deliberate no-place, or a made-up country (I’ve not yet succeeded in reading a J.M. Coetzee or José Saramago novel, for instance). I gave up on the Giller Prize-winning Study for Obedience when its first ten pages gave no clear sense of its geographical or temporal setting. When there’s no detail to latch onto, disorientation usually leads me to turn to another more realist book in preference.

They is, in fact, set in an ironically idyllic Britain. There are lovely descriptions of the land during different seasons: roses, sunsets, wheat fields, birdsong. This is in contrast with the disquiet permeating the narrator’s everyday life. She is part of a dispersed, itinerant creative community whose members come and go, hiding their work and doing their best to avoid the nameless enforcers who patrol the country to destroy art and quash emotion and individual endeavours. Certain artists of her acquaintance have been maimed or disappeared. For all the public enshrinement of teamwork, the normies the book portrays seem purely mean-spirited: children torture animals for kicks.

A case could be made that Dick was aiming at universality – this could happen anywhere – but the combination of imprecision and flat, declarative sentences left me cold.

“We’re all frightened. We must live with it. Russell and Jane will be here tomorrow. They got through London. I’ll be sleeping in the room opposite yours tonight. You are over-tired; it’s the strain.”

“Subscribing to current social fashions, I gave a small party, inviting all my neighbours. They all talked at the same time. No one listened to anyone else. No one laughed. Only Tim and I smiled at each other. They felt uneasy because there was no television set.”

In terms of world-building, everything is either unexplained or revealed abruptly through unsubtle dialogue. I came away with no sense of the narrator or any of the many secondary characters, who are little more than a name. Funny that the most consistent presence is that of her dog, who is never given the dignity of a name. (It’s only ever “my dog,” when a creature so important to her would surely be referred to as a friend.) While the two authors were probably poles apart ideologically, I thought I spied the ghost of Ayn Rand in the awe surrounding individual achievement.

It’s comforting to try to believe what Hurst says about the persistence of art – “We can all add to the treasure, however short the time left may be. It can’t all be destroyed. Some of it will remain for those who come after us” – but this portrait of underground artists in a parallel modern Britain failed to move me. (New purchase at sale price from Faber website) [107 pages]

Booker Prize 2021: Longlist Reading and Shortlist Predictions

The 2021 Booker Prize shortlist will be announced tomorrow, September 14th, at 4 p.m. via a livestream. I’ve managed to read or skim eight of 13 from the longlist, only one of which I sought out specifically after it was nominated (An Island – the one no one had heard of; it turns out it was released by a publisher based just 1.5 miles from my home!). I review my four most recent reads below, followed by excerpts of reviews of ones I read a while ago and my brief thoughts on the rest, including what I expect to see on tomorrow’s shortlist.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

Why ever did I put this on my Most Anticipated list of the year and pre-order a signed copy?! I’m a half-hearted Ishiguro fan at best (I love Nocturnes but am lukewarm on the other four I’ve read, including his Booker winner) and should have known that his take on AI would be no more inspiring than Ian McEwan’s (Machines Like Me) a couple of years back.

Why ever did I put this on my Most Anticipated list of the year and pre-order a signed copy?! I’m a half-hearted Ishiguro fan at best (I love Nocturnes but am lukewarm on the other four I’ve read, including his Booker winner) and should have known that his take on AI would be no more inspiring than Ian McEwan’s (Machines Like Me) a couple of years back.

Klara is an Artificial Friend purchased as part of an effort to combat the epidemic of teenage loneliness – specifically, to cheer up her owner, Josie, who suffers from an unspecified illness and is in love with her neighbour, Rick, a bright boy who remains excluded. Klara thinks of the sun as a god, praying to it and eventually making a costly bargain to try to secure Josie’s future health.

Part One’s 45 pages are slow and tedious; the backstory could have been dispensed with in five fairy tale-like pages. There’s a YA air to the story: for much of the length I might have been rereading Everything, Everything. In fact, when I saw Ishiguro introduce the novel at a Guardian/Faber launch event, he revealed that it arose from a story he wrote for children. The further I got, the more I was sure I’d read it all before. That’s because the plot is pretty much identical to the final story in Mary South’s You Will Never Be Forgotten.

Klara’s highly precise diction, referring to everyone in the third person, also gives this the feeling of translated fiction. While that is part of Ishiguro’s aim, of course – to explore the necessarily limited perspective and speech of a nonhuman entity (“Her ability to absorb and blend everything she sees around her is quite amazing”) – it makes the prose dull and belaboured. The secondary characters include various campy villains, the ‘big reveals’ aren’t worth waiting for, and the ending is laughably reminiscent of Toy Story. This took me months and months to force myself through. What a slog! (New purchase)

An Island by Karen Jennings (2019)

Seventy-year-old Samuel has been an island lighthouse keeper for 14 years when a brown-skinned stranger washes up on his beach. Sole survivor from a sunken refugee boat, the man has no English, so they communicate through gestures. Jennings convincingly details the rigors of the isolated life here: Samuel dug his own toilet pipes, burns his trash once a week, and gets regular deliveries from a supply boat. Nothing is wasted and everything is appreciated here, even the thirdhand magazines and videotapes he inherits from the mainland.

Seventy-year-old Samuel has been an island lighthouse keeper for 14 years when a brown-skinned stranger washes up on his beach. Sole survivor from a sunken refugee boat, the man has no English, so they communicate through gestures. Jennings convincingly details the rigors of the isolated life here: Samuel dug his own toilet pipes, burns his trash once a week, and gets regular deliveries from a supply boat. Nothing is wasted and everything is appreciated here, even the thirdhand magazines and videotapes he inherits from the mainland.

Although the core action takes place in just four days, Samuel is so mentally shaky that his memories start getting mixed up with real life. We learn that he has been a father, a prisoner and a beggar. Jennings is South African, and in this parallel Africa, racial hierarchy still holds sway and a general became a dictator through a military coup. Samuel’s father was involved in the independence movement, while Samuel himself was arrested for resisting the dictator.

The novella’s themes – jealousy, mistrust, possessiveness, suspicion, and a return to primitive violence – are of perennial relevance. Somehow, it didn’t particularly resonate for me. It’s not dissimilar in style to J. M. Coetzee’s vague but brutal detachment, and it’s a highly male vision à la Doggerland. Though highly readable, it’s ultimately a somewhat thin fable with a predictable message about xenophobia. Still, I’m glad I discovered it through the Booker longlist.

My thanks to Holland House for the free copy for review.

Bewilderment by Richard Powers

This has just as much of an environmentalist conscience as The Overstory, but a more intimate scope, focusing on a father and son who journey together in memory and imagination as well as in real life. The novel leaps between spheres: between the public eye, where neurodivergent Robin is a scientific marvel and an environmental activist, and the privacy of family life; between an ailing Earth and the other planets Theo studies; and between the humdrum of daily existence and the magic of another state where Robin can reconnect with his late mother. When I came to the end, I felt despondent and overwhelmed. But as time has passed, the book’s feral beauty has stuck with me. The pure sense of wonder Robin embodies is worth imitating. (Review forthcoming for BookBrowse.)

This has just as much of an environmentalist conscience as The Overstory, but a more intimate scope, focusing on a father and son who journey together in memory and imagination as well as in real life. The novel leaps between spheres: between the public eye, where neurodivergent Robin is a scientific marvel and an environmental activist, and the privacy of family life; between an ailing Earth and the other planets Theo studies; and between the humdrum of daily existence and the magic of another state where Robin can reconnect with his late mother. When I came to the end, I felt despondent and overwhelmed. But as time has passed, the book’s feral beauty has stuck with me. The pure sense of wonder Robin embodies is worth imitating. (Review forthcoming for BookBrowse.)

China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

Sahota appeared on Granta’s list of Best Young British Novelists in 2013 and was previously shortlisted for The Year of the Runaways, a beautiful novel tracking the difficult paths of four Indian immigrants seeking a new life in Sheffield.

Sahota appeared on Granta’s list of Best Young British Novelists in 2013 and was previously shortlisted for The Year of the Runaways, a beautiful novel tracking the difficult paths of four Indian immigrants seeking a new life in Sheffield.

Three brides for three brothers: as Laura notes, it sounds like the setup of a folk tale, and there’s a timeless feel to this short novel set in the Punjab in the late 1920s and 1990s – it also reminded me of biblical stories like those of Jacob and Leah and David and Bathsheba. Mehar is one of three teenage girls married off to a set of brothers. The twist is that, because they wear heavy veils and only meet with their husbands at night for procreation, they don’t know which is which. Mehar is sure she’s worked out which brother is her husband, but her well-meaning curiosity has lasting consequences.

In the later storyline, a teenage addict returns from England to his ancestral estate to try to get clean before going to university and becomes captivated by the story of his great-grandmother and her sister wives, who were confined to the china room. The characters are real enough to touch, and the period and place details make the setting vivid. The two threads both explore limitations and desire, and the way the historical narrative keeps surging back in makes things surprisingly taut. See also Susan’s review. (Read via NetGalley)

Other reads, in brief:

(Links to my full reviews)

Second Place by Rachel Cusk: Significantly more readable than the Outline trilogy and with psychological depths worth pondering, though Freudian symbolism makes it old-fashioned. M’s voice is appealing, as is the marshy setting and its isolated dwellings. This feels like a place outside of time. The characters act and speak in ways that no real person ever would – the novel is most like a play: melodramatic and full of lofty pronouncements. Interesting, but nothing to take to heart; Cusk’s work is always intimidating in its cleverness.

Second Place by Rachel Cusk: Significantly more readable than the Outline trilogy and with psychological depths worth pondering, though Freudian symbolism makes it old-fashioned. M’s voice is appealing, as is the marshy setting and its isolated dwellings. This feels like a place outside of time. The characters act and speak in ways that no real person ever would – the novel is most like a play: melodramatic and full of lofty pronouncements. Interesting, but nothing to take to heart; Cusk’s work is always intimidating in its cleverness.

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson: In 1972, Clara, a plucky seven-year-old, sits vigil for the return of her sixteen-year-old sister, who ran away from home; and their neighbour, who’s in the hospital. One day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes in next door. This is Liam Kane, who inherited the house from a family friend. Like Lawson’s other works, this is a slow burner featuring troubled families. It’s a tender and inviting story I’d recommend to readers of Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Strout and Anne Tyler.

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson: In 1972, Clara, a plucky seven-year-old, sits vigil for the return of her sixteen-year-old sister, who ran away from home; and their neighbour, who’s in the hospital. One day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes in next door. This is Liam Kane, who inherited the house from a family friend. Like Lawson’s other works, this is a slow burner featuring troubled families. It’s a tender and inviting story I’d recommend to readers of Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Strout and Anne Tyler.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: This starts as a flippant skewering of modern life. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.” Midway through the book, she gets a wake-up call when her mother summons her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. It’s the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. Funny, but with an ache behind it.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: This starts as a flippant skewering of modern life. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.” Midway through the book, she gets a wake-up call when her mother summons her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. It’s the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. Funny, but with an ache behind it.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford: While I loved the premise, the execution didn’t live up to it. Spufford calls this an act of “literary resurrection” of five figures who survive a South London bombing. But these particular characters don’t seem worth spending time with; their narratives don’t connect up tightly, as expected, and feel derivative, serving only as ways to introduce issues (e.g. mental illness, sexual assault, racial violence, eating disorders) and try out different time periods. I would have taken a whole novel about Ben.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford: While I loved the premise, the execution didn’t live up to it. Spufford calls this an act of “literary resurrection” of five figures who survive a South London bombing. But these particular characters don’t seem worth spending time with; their narratives don’t connect up tightly, as expected, and feel derivative, serving only as ways to introduce issues (e.g. mental illness, sexual assault, racial violence, eating disorders) and try out different time periods. I would have taken a whole novel about Ben.

This leaves five more: Great Circle (by Maggie Shipstead) I found bloated and slow when I tried it in early July, but I’m going to give it another go when my library hold comes in. The Sweetness of Water (Nathan Harris) I might try if my library acquired it, but I’m not too bothered – from Eric’s review on Lonesome Reader, it sounds like it’s a slavery narrative by the numbers. I’m not at all interested in the novels by Anuk Arudpragasam, Damon Galgut, or Nadifa Mohamed but can’t say precisely why; their descriptions just don’t excite me.

This leaves five more: Great Circle (by Maggie Shipstead) I found bloated and slow when I tried it in early July, but I’m going to give it another go when my library hold comes in. The Sweetness of Water (Nathan Harris) I might try if my library acquired it, but I’m not too bothered – from Eric’s review on Lonesome Reader, it sounds like it’s a slavery narrative by the numbers. I’m not at all interested in the novels by Anuk Arudpragasam, Damon Galgut, or Nadifa Mohamed but can’t say precisely why; their descriptions just don’t excite me.

Here’s what I expect to still be in the running after tomorrow. Clear-eyed, profound, international; bridging historical and contemporary; much that’s unabashedly highbrow.

- Second Place by Rachel Cusk

The Promise by Damon Galgut (will win)

The Promise by Damon Galgut (will win)- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Bewilderment by Richard Powers

- China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

- Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford

What have you read from the longlist? What do you expect to be shortlisted?

Four Recent Review Books: Ernaux, Nunez, Rubin & Scharer

Two nonfiction books: a frank account of an abortion; clutter-busting techniques.

Two novels: amusing intellectual fare featuring a big dog or the Parisian Surrealists.

Happening by Annie Ernaux (2000; English translation, 2019)

[Translated from the French by Tanya Leslie]

“I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled,” Ernaux writes. In 1963, when she was 23 and living in a student residence in Rouen, she realized she was pregnant. An appointment with a gynecologist set out the facts starkly: “Pregnancy certificate of: Mademoiselle Annie Duchesne. Date of delivery: 8 July, 1964. I saw summer, sunshine. I tore up the certificate.” Abortion was illegal in France at that time. Ernaux tried to take things into her own hands – “plunging a knitting needle into a womb weighed little next to ruining one’s career” – but couldn’t go through with it. Instead she went to the home of a middle-aged nurse she’d heard about…

“I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled,” Ernaux writes. In 1963, when she was 23 and living in a student residence in Rouen, she realized she was pregnant. An appointment with a gynecologist set out the facts starkly: “Pregnancy certificate of: Mademoiselle Annie Duchesne. Date of delivery: 8 July, 1964. I saw summer, sunshine. I tore up the certificate.” Abortion was illegal in France at that time. Ernaux tried to take things into her own hands – “plunging a knitting needle into a womb weighed little next to ruining one’s career” – but couldn’t go through with it. Instead she went to the home of a middle-aged nurse she’d heard about…

This very short book (just 60-some pages) is told in a matter-of-fact style – apart from the climactic moment when her pregnancy ends: “It burst forth like a grenade, in a spray of water that splashed the door. I saw a baby doll dangling from my loins at the end of a reddish cord.” It’s such a garish image, almost cartoonish, that I didn’t know whether to laugh or be horrified. Mostly, Ernaux reflects on memory and the reconstruction of events. I haven’t read many nonfiction accounts of abortion/miscarriage and for that reason found this interesting, but it was perhaps too brief and detached for me to be fully engaged.

My rating:

With thanks to Fitzcarraldo Editions for the free copy for review.

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez (2018)

“Does something bad happen to the dog?” We animal lovers are wary when approaching a book about a pet. Nunez playfully anticipates that question as she has her unnamed female narrator reflect on her duty of care to her dead friend’s dog. The narrator is a writer and academic – like her late friend, a Bellovian womanizer who recently committed suicide, leaving behind two ex-wives, a widow, and Apollo the aging Great Dane. She addresses the friend directly as “you” for almost the whole book, which unfolds – in a similar style to Jenny Offill’s Department of Speculation – via quotations, aphorisms, and stories from literary history as well as mini-incidents from a life.

“Does something bad happen to the dog?” We animal lovers are wary when approaching a book about a pet. Nunez playfully anticipates that question as she has her unnamed female narrator reflect on her duty of care to her dead friend’s dog. The narrator is a writer and academic – like her late friend, a Bellovian womanizer who recently committed suicide, leaving behind two ex-wives, a widow, and Apollo the aging Great Dane. She addresses the friend directly as “you” for almost the whole book, which unfolds – in a similar style to Jenny Offill’s Department of Speculation – via quotations, aphorisms, and stories from literary history as well as mini-incidents from a life.

This won the 2018 National Book Award in the USA and is an unashamedly high-brow work whose intertextuality comes through in direct allusions to many classic works of autofiction (Coetzee, Knausgaard and Lessing) and/or doggy lit (Ackerley; Coetzee again – Disgrace). As Apollo starts to take up more physical, mental and emotional space in the narrator’s life, she waits for a miracle that will allow her to keep him despite an eviction notice and muses on lots of questions: Is all writing autobiographical? Why does animal suffering pain us so much (especially compared to human suffering)? I was impressed: it feels like Nunez has encapsulated everything she’s ever known or thought about, all in just over 200 pages, and alongside a heart-warming little plot. (Animal lovers need not fear.)

My rating:

With thanks to Virago for the free copy for review.

Outer Order, Inner Calm: Declutter and Organize to Make More Room for Happiness by Gretchen Rubin (2019)

What with all the debate over Marie Kondo’s clutter-reducing tactics, the timing is perfect for this practical guide to culling and organizing all the stuff that piles up around us at home and at work. Unlike the rest of Rubin’s self-help books, this is not a narrative but a set of tips – 150 of them! It’s not so much a book to read straight through as one to keep at your bedside and read a few pages to summon up motivation for the next tidying challenge.

What with all the debate over Marie Kondo’s clutter-reducing tactics, the timing is perfect for this practical guide to culling and organizing all the stuff that piles up around us at home and at work. Unlike the rest of Rubin’s self-help books, this is not a narrative but a set of tips – 150 of them! It’s not so much a book to read straight through as one to keep at your bedside and read a few pages to summon up motivation for the next tidying challenge.

Famously, Kondo advises one to ask whether an item sparks joy. Rubin’s central questions are more down-to-earth: Do I need it? Do I love it? Do I use it? With no index, the book is a bit difficult to navigate; you just have to flip through until you find what you want. The advice seems in something of a random order and can be slightly repetitive. But since this is really meant as a book of inspiration, I think it will be a useful jumping-off point for anyone trying to get on top of clutter. I plan to work through the closet checklist before I pass the book to my sister – who’s dealing with a basement full of stuff after she and her second husband merged their households. If I could add one page, it would be a flowchart of what to do with unwanted stuff that corresponds to the latest green recommendations.

Famously, Kondo advises one to ask whether an item sparks joy. Rubin’s central questions are more down-to-earth: Do I need it? Do I love it? Do I use it? With no index, the book is a bit difficult to navigate; you just have to flip through until you find what you want. The advice seems in something of a random order and can be slightly repetitive. But since this is really meant as a book of inspiration, I think it will be a useful jumping-off point for anyone trying to get on top of clutter. I plan to work through the closet checklist before I pass the book to my sister – who’s dealing with a basement full of stuff after she and her second husband merged their households. If I could add one page, it would be a flowchart of what to do with unwanted stuff that corresponds to the latest green recommendations.

My rating:

With thanks to Two Roads for the free copy for review.

The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer (2019)

This novel about Lee Miller’s relationship with Man Ray is in the same vein as The Paris Wife, Z, Loving Frank and Frieda: all of these have sought to rescue a historical woman from the shadow of a celebrated, charismatic male and tell her own fascinating life story. Scharer captures the bohemian atmosphere of 1929–30 Paris in elegant but accessible prose. Along with the central pair we meet others from the Dada group plus Jean Cocteau, and get a glimpse of Josephine Baker. The novel is nearly 100 pages too long, I think, such that my interest in the politics of the central relationship – Man becomes too possessive and Lee starts to act out, longing for freedom again – started to wane.

This novel about Lee Miller’s relationship with Man Ray is in the same vein as The Paris Wife, Z, Loving Frank and Frieda: all of these have sought to rescue a historical woman from the shadow of a celebrated, charismatic male and tell her own fascinating life story. Scharer captures the bohemian atmosphere of 1929–30 Paris in elegant but accessible prose. Along with the central pair we meet others from the Dada group plus Jean Cocteau, and get a glimpse of Josephine Baker. The novel is nearly 100 pages too long, I think, such that my interest in the politics of the central relationship – Man becomes too possessive and Lee starts to act out, longing for freedom again – started to wane.

Miller was a photographer as well as a model and journalist, and this is an appropriately visual novel that’s interested in appearances, lighting and what gets preserved for posterity. It’s also fairly sexually explicit for literary fiction, sometimes unnecessarily so, so keep that in mind if it’s likely to bother you. I especially enjoyed the brief flashes of Lee at other points in her life: in London during the Blitz, photographing the aftermath of the war in Germany (there’s a famous image of her in Hitler’s bathtub), and hoping she’s more than just a washed-up alcoholic in the 1960s. It would be a boon to have a prior interest in or some knowledge of the Surrealists.

My rating:

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Last-Minute Thoughts on the Booker Longlist

Tomorrow, the 20th, the Man Booker Prize shortlist will be announced. This must be my worst showing for many years: I’ve read just two of the longlisted books, and both were such disappointments I had to wonder why they’d been nominated at all. I have six of the others on request from the public library; of them I’m most keen to read The Overstory and Sabrina, the first graphic novel to have been recognized (the others are by Gunaratne, Johnson, Kushner and Ryan, but I’ll likely cancel my holds if they don’t make the shortlist). I’d read Robin Robertson’s novel-in-verse if I ever managed to get hold of a copy, but I’ve decided I’m not interested in the other four nominees (Bauer, Burns, Edugyan, Ondaatje*).

The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh

(Excerpted from my upcoming review for New Books magazine’s Booker Prize roundup.)

The first word of The Water Cure may be “Once,” but what follows is no fairy tale. Here’s the rest of that sentence: “Once we have a father, but our father dies without us noticing.” The tense seems all wrong; surely it should be “had” and “died”? From the very first line, then, Sophie Mackintosh’s debut novel has the reader wrong-footed, and there are many more moments of confusion to come. The other thing to notice in the opening sentence is the use of the first person plural. That “we” refers to three sisters: Grace, Lia and Sky. After the death of their father, King, it’s just them and their mother in a grand house on a remote island.

The first word of The Water Cure may be “Once,” but what follows is no fairy tale. Here’s the rest of that sentence: “Once we have a father, but our father dies without us noticing.” The tense seems all wrong; surely it should be “had” and “died”? From the very first line, then, Sophie Mackintosh’s debut novel has the reader wrong-footed, and there are many more moments of confusion to come. The other thing to notice in the opening sentence is the use of the first person plural. That “we” refers to three sisters: Grace, Lia and Sky. After the death of their father, King, it’s just them and their mother in a grand house on a remote island.

There are frequent flashbacks to times when damaged women used to come here for therapy that sounds more like torture. The sisters still engage in similar sadomasochistic practices: sitting in a hot sauna until they faint, putting their hands and feet in buckets of ice, and playing the “drowning game” in the pool by putting on a dress laced with lead weights. Despite their isolation, the sisters are still affected by the world at large. At the end of Part I, three shipwrecked men wash up on shore and request sanctuary. The men represent new temptations and a threat to the sisters’ comfort zone.

This is a strange and disorienting book. The atmosphere – lonely and lowering – is the best thing about it. Its setup is somewhat reminiscent of two Shakespeare plays, King Lear and The Tempest. With the exception of a few lines like “we look towards the rounded glow of the horizon, the air peach-ripe with toxicity,” the prose draws attention to itself in a bad way: it’s consciously literary and overwritten. In terms of the plot, it is difficult to understand, at the most basic level, what is going on and why. Speculative novels with themes of women’s repression are a dime a dozen nowadays, and the interested reader will find a better example than this one.

My rating:

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Conversations with Friends was one of last year’s sleeper hits and a surprise favorite of mine. You may remember that I was part of an official shadow panel for the 2017 Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, which I was pleased to see Sally Rooney win. So I jumped at the chance to read her follow-up novel, which has been earning high praise from critics and ordinary readers alike as being even better than her debut. Alas, though, I was let down.

Normal People is very similar to Tender – which for some will be high praise indeed, though I never managed to finish Belinda McKeon’s novel – in that both realistically address the intimacy between a young woman and a young man during their university days and draw class and town-and-country distinctions (the latter of which might not mean much to those who are unfamiliar with Ireland).

Normal People is very similar to Tender – which for some will be high praise indeed, though I never managed to finish Belinda McKeon’s novel – in that both realistically address the intimacy between a young woman and a young man during their university days and draw class and town-and-country distinctions (the latter of which might not mean much to those who are unfamiliar with Ireland).

The central characters here are two loners: Marianne Sheridan, who lives in a white mansion with her distant mother and sadistic older brother Alan, and Connell Waldron, whose single mother cleans Marianne’s house. Connell doesn’t know who his father is; Marianne’s father died when she was 13, but good riddance – he hit her and her mother. Marianne and Connell start hooking up during high school in Carricklea, but Connell keeps their relationship a secret because Marianne is perceived as strange and unpopular. At Trinity College Dublin they struggle to fit in and keep falling into bed with each other even though they’re technically seeing other people.

The novel, which takes place between 2011 and 2015, keeps going back and forth in time by weeks or months, jumping forward and then filling in the intervening time with flashbacks. I kept waiting for more to happen, skimming ahead to see if there would be anything more to it than drunken college parties and frank sex scenes. The answer is: not really; that’s mostly what the book is composed of.

I can see what Rooney is trying to do here (she makes it plain in the next-to-last paragraph): to show how one temporary, almost accidental relationship can change the partners for the better, giving Connell the impetus to pursue writing and Marianne the confidence to believe she is loveable, just like ‘normal people’. It is appealing to see into these characters’ heads and compare what they think of themselves and each other with their awareness of what others think. But page to page it is pretty tedious, and fairly unsubtle.

I was interested to learn that Rooney was writing this at the same time as Conversations, and initially intended it to be short stories. It’s possible I would have appreciated it more in that form.

My rating:

My thanks to Faber & Faber for the free copy for review.

*I’ve only ever read the memoir Running in the Family plus a poetry collection by Ondaatje. I have a copy of The English Patient on the shelf and have felt guilty for years about not reading it, especially after it won the “Golden Booker” this past summer (see Annabel’s report on the ceremony). I had grand plans of reading all the Booker winners on my shelf – also including Carey and Keneally – in advance of the 50th anniversary celebrations, but didn’t even make it through the books I started by the two South African winners; my aborted mini-reviews are part of the Shiny New Books coverage here. (There are also excerpts from my reviews of Bring Up the Bodies, The Sellout and Lincoln in the Bardo here.)

*I’ve only ever read the memoir Running in the Family plus a poetry collection by Ondaatje. I have a copy of The English Patient on the shelf and have felt guilty for years about not reading it, especially after it won the “Golden Booker” this past summer (see Annabel’s report on the ceremony). I had grand plans of reading all the Booker winners on my shelf – also including Carey and Keneally – in advance of the 50th anniversary celebrations, but didn’t even make it through the books I started by the two South African winners; my aborted mini-reviews are part of the Shiny New Books coverage here. (There are also excerpts from my reviews of Bring Up the Bodies, The Sellout and Lincoln in the Bardo here.)

Last year I’d read enough from the Booker longlist to make predictions and a wish list, but this year I have no clue. I’ll just have a look at the shortlist tomorrow and see if any of the remaining contenders appeal.

What have you managed to read from the Booker longlist? Do you have any predictions for the shortlist?

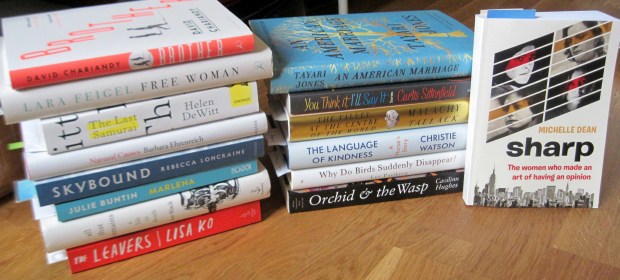

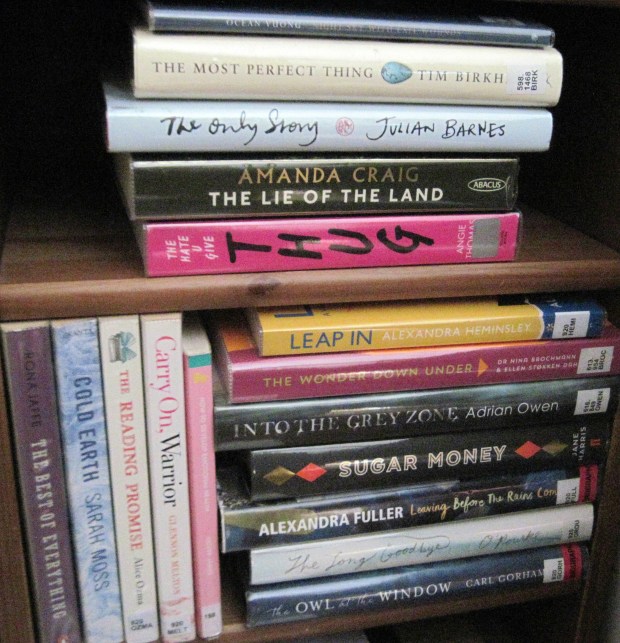

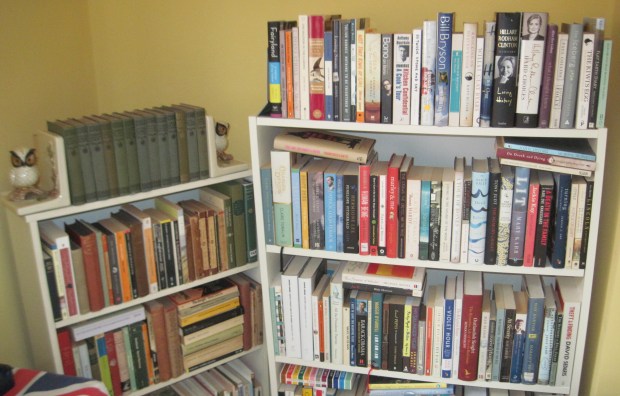

Book Triage

I feel like I have more books staring at me than ever before. I could blame free library reservations and a trip to Wigtown, but there’s one more major reason for the books stacking up: an utter lack of restraint when it comes to requesting or accepting books for review. I’ve had loads of books coming through the door in the past month or so. Some were offered to me by authors or publishers via Goodreads, Twitter or my blog’s contact form. Others I sent e-mails to request after I saw tempting reviews in the Guardian or previews on Susan’s blog.

Of course I want to read all of these books. I really want to read most of them. Otherwise I wouldn’t have gone to the trouble of requesting, borrowing or buying them. But even so, there’s only so much time. It’s not just a simple matter of picking up the book(s) from the stack that I most feel like reading at a given moment anymore. No, it’s become a triage process whereby I have to assess them by order of urgency.

So, what are my priorities? Here’s a baker’s dozen, in photos.

- Wellcome Book Prize shortlist reading. I’m on the last of six now; this is for the blog tour coming up next week.

- Library books that are due in early May and requested after me.

- Books I’ve requested for a blog review, in release date order. I feel so behind that you can expect some doubled-up reviews or mini-reviews in roundup form.

- Books I’ve agreed to review for another outlet, even if that’s just Goodreads.

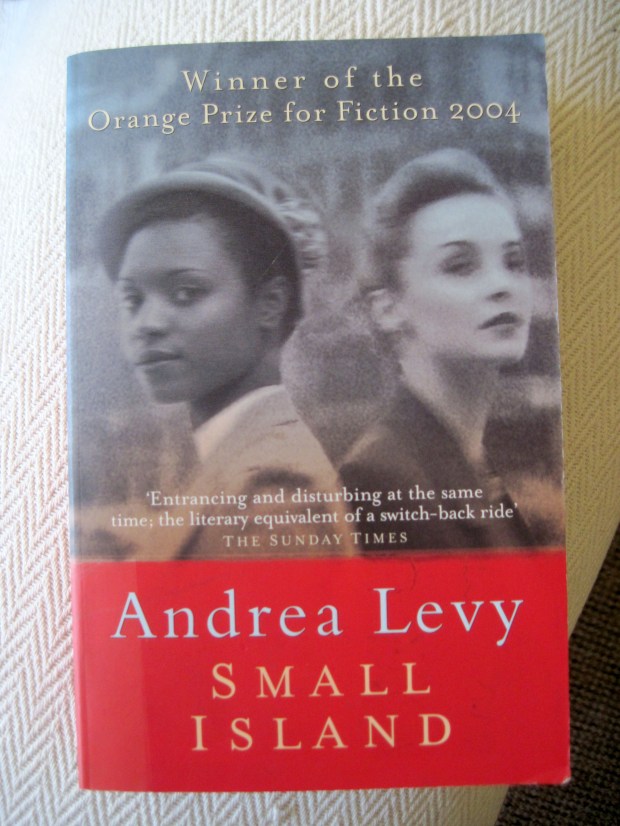

- My first-ever buddy read: Small Island with Buried in Print and Consumed by Ink, arranged months ago. Join us!

- Month- or season-specific reads.

- Public library books with no current renewal issues.

- Booker Prize winners for the 50th anniversary this summer – I’ll at least review the Coetzee for Shiny New Books, and perhaps a few more on the blog if I get the time.

- Three more Iris Murdoch novels to read as part of Liz’s #IMReadalong later on in the year, starting in June.

- Bibliotherapy prescriptions.

- Books I’ve set aside temporarily, generally because I have enthusiastically started too many at once and had to put some down to pick up more time-sensitive review books. Many of these I was enjoying very much and could see turning out to be 4- or even 5-star reads (especially Brooks, Frame and Matthiessen); others I might end up abandoning.

- University library books, which can be renewed pretty much indefinitely.

- Every other book I own, even if I had it eyed up for a particular challenge. My vague resolution to read lots of travel books and biographies has pretty much gone by the wayside so far. I also have barely managed a single classic. Sigh! There’s still two-thirds of the year left, but I certainly won’t be managing the one a month from these genres that I proposed.

What’s your book triage situation like?

Booker Longlist Mini Reviews

Tomorrow the Man Booker Prize shortlist will be announced. I’d already read and reviewed four of the nominees (see my quick impressions here), and in the time since the longlist announcement I’ve managed to read another three and ruled out one more. Two were terrific; another was pretty good; the last I’ll never know because it’s clear to me I won’t read it.

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

What a terrific, propulsive tale Burnet has woven out of a real-life (I think) nineteenth-century Scottish murder case. The seams between fact and fiction are so subtle you might forget you’re reading a novel, but it’s clear the author has taken great care in assembling his “documents”: witness testimonies, medical reports, a psychologist’s assessment, trial records, and – the heart of the book and the most fascinating section – a memoir written by the murderer himself. As you’re reading it you believe Roddy implicitly and feel deeply for his humiliation (the meeting with the factor and the rejection by Flora are especially agonizing scenes), but as soon as you move on to the more ‘objective’ pieces you question how he depicted things. I went back and read parts of his account two or three times, wondering how his memories squared with the facts of the case. A great one for fans of Alias Grace, though I liked this much better. This is my favorite from the Booker longlist so far.

What a terrific, propulsive tale Burnet has woven out of a real-life (I think) nineteenth-century Scottish murder case. The seams between fact and fiction are so subtle you might forget you’re reading a novel, but it’s clear the author has taken great care in assembling his “documents”: witness testimonies, medical reports, a psychologist’s assessment, trial records, and – the heart of the book and the most fascinating section – a memoir written by the murderer himself. As you’re reading it you believe Roddy implicitly and feel deeply for his humiliation (the meeting with the factor and the rejection by Flora are especially agonizing scenes), but as soon as you move on to the more ‘objective’ pieces you question how he depicted things. I went back and read parts of his account two or three times, wondering how his memories squared with the facts of the case. A great one for fans of Alias Grace, though I liked this much better. This is my favorite from the Booker longlist so far.

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh

“I often felt there was something wired weird in my brain, a problem so complicated only a lobotomy could solve it—I’d need a whole new mind or a whole new life.” This isn’t so much a book to enjoy as one to endure. Being in Eileen’s mind is profoundly unsettling. She’s simultaneously fascinated and disgusted by bodies; she longs for her alcoholic father’s approval even as she wonders whether she could get away with killing him. They live a life apart in their rundown home in X-ville, New England, and Eileen can’t wait to get out by whatever means necessary. When Rebecca St. John joins the staff of the boys’ prison where Eileen works, she hopes this alluring woman will be her ticket out of town.

“I often felt there was something wired weird in my brain, a problem so complicated only a lobotomy could solve it—I’d need a whole new mind or a whole new life.” This isn’t so much a book to enjoy as one to endure. Being in Eileen’s mind is profoundly unsettling. She’s simultaneously fascinated and disgusted by bodies; she longs for her alcoholic father’s approval even as she wonders whether she could get away with killing him. They live a life apart in their rundown home in X-ville, New England, and Eileen can’t wait to get out by whatever means necessary. When Rebecca St. John joins the staff of the boys’ prison where Eileen works, she hopes this alluring woman will be her ticket out of town.

There’s a creepy Hitchcock flavor to parts of the novel (I imagined Eileen played by Patricia Hitchcock as in Strangers on a Train, with Rebecca as Gene Tierney in Laura), and a nice late twist – but Moshfegh sure makes you wait for it. In the meantime you have to put up with the tedium and squalor of Eileen’s daily life, and there’s no escape from her mind. This is one of those rare novels I would have preferred to be in the third person: it would allow the reader to come to his/her own conclusions about Eileen’s psychology, and would have created more suspense because Eileen’s hindsight wouldn’t result in such heavy foreshadowing. I expected suspense but actually found this fairly slow and somewhat short of gripping.

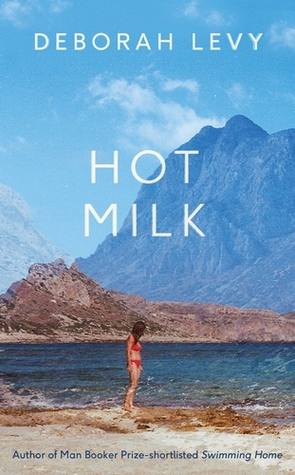

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy

This is a most unusual mother–daughter story, set on the southern coast of Spain. Twenty-five-year-old Sofia Papastergiadis has put off her anthropology PhD to accompany her mother, Rose, on a sort of pilgrimage to Dr. Gómez’s clinic to assess what’s wrong with Rose’s legs. What I loved about this novel is the uncertainty about who each character really is. Is Rose an invalid or a first-class hypochondriac? Is Dr. Gómez a miracle worker or a quack who’s fleeced them out of 25,000 euros? As a narrator, Sofia pretends to objective anthropological observation but is just as confused by her actions as we are: she seems to deliberately court jellyfish stings, is simultaneously jealous and contemptuous of her Greek father’s young second wife, and sleeps with both Juan and Ingrid.

This is a most unusual mother–daughter story, set on the southern coast of Spain. Twenty-five-year-old Sofia Papastergiadis has put off her anthropology PhD to accompany her mother, Rose, on a sort of pilgrimage to Dr. Gómez’s clinic to assess what’s wrong with Rose’s legs. What I loved about this novel is the uncertainty about who each character really is. Is Rose an invalid or a first-class hypochondriac? Is Dr. Gómez a miracle worker or a quack who’s fleeced them out of 25,000 euros? As a narrator, Sofia pretends to objective anthropological observation but is just as confused by her actions as we are: she seems to deliberately court jellyfish stings, is simultaneously jealous and contemptuous of her Greek father’s young second wife, and sleeps with both Juan and Ingrid.

Levy imbues the novel’s relationships with psychological and mythological significance, especially the Medusa story. I don’t think the ending quite fits the tone, but overall this is a quick and worthwhile read. At the same time, it’s such an odd story that it will keep you thinking about the characters. A great entry I’d be happy to see make the shortlist.

[One I won’t be reading: The Schooldays of Jesus by J.M. Coetzee. I opened up the prequel, The Childhood of Jesus, and could only manage the first chapter. I quickly skimmed the rest but found it unutterably dull. It would take me a lot of secondary source reading to try to understand what was going on here allegorically, and it’s not made me look forward to trying more from Coetzee.]

As for the rest: I have All That Man Is by David Szalay and Serious Sweet by A.L. Kennedy on my Kindle and will probably read them whether or not they’re shortlisted. The same goes for Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien, for which I’m third in a library hold queue. I’d still like to get hold of The Many by Wyl Menmuir. That leaves just Hystopia by David Means, which I can’t say I have much interest in.

As for the rest: I have All That Man Is by David Szalay and Serious Sweet by A.L. Kennedy on my Kindle and will probably read them whether or not they’re shortlisted. The same goes for Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien, for which I’m third in a library hold queue. I’d still like to get hold of The Many by Wyl Menmuir. That leaves just Hystopia by David Means, which I can’t say I have much interest in.

I rarely feel like I have enough of a base of experience to make accurate predictions, but if I had to guess which six books would make it through tomorrow, I would pick:

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

The Schooldays of Jesus by J.M. Coetzee

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy

The North Water by Ian McGuire

My Name Is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

That would be three men and three women, and a pretty good mix of countries and genres. I’d be happy with that list.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

Yesterday was also my 36th birthday. A dismally wet Monday may not be ideal for a birthday, but I’d had the whole previous weekend for celebrating so can’t really complain. Saturday was a very Newbury day of volunteer gardening in the drizzle; an excellent lunch at

Yesterday was also my 36th birthday. A dismally wet Monday may not be ideal for a birthday, but I’d had the whole previous weekend for celebrating so can’t really complain. Saturday was a very Newbury day of volunteer gardening in the drizzle; an excellent lunch at

One of the best parts of preparing for my birthday is finding recipes for my husband to make for me. This year I picked a Chocolate Orange Truffle Cake from Perfect Chocolate Desserts (which includes photographs of every step), a veganized

One of the best parts of preparing for my birthday is finding recipes for my husband to make for me. This year I picked a Chocolate Orange Truffle Cake from Perfect Chocolate Desserts (which includes photographs of every step), a veganized

And then there’s the books I’d simply never heard of. Of these I’m most interested in His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet, based on a true-life murder in Scotland in the 1860s, and The Many by Wyl Menmuir, a debut novella about a village newcomer.

And then there’s the books I’d simply never heard of. Of these I’m most interested in His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet, based on a true-life murder in Scotland in the 1860s, and The Many by Wyl Menmuir, a debut novella about a village newcomer.